Executive Summary

The “Imposter Syndrome,” which affects professionals across industries and at every stage of their careers, is relatively common and refers to the tendency many have to doubt their own abilities and accomplishments, and results in the fear of being “found out” as a fraud (even if the reality is that they really are a bona fide expert!).

A lesser-known challenge that many professionals – particularly those in fields where their interactions with clients can result in life-altering consequences – run up against after they’ve got some education and experience under their belts is the realization that, despite what they’ve already learned, there’s an ocean of knowledge and expertise between where they are where they feel they need to be to best serve their clients. Which similarly can result in a decrease in confidence even as their actual skill to serve clients is objectively increasing.

In this week’s #OfficeHours with @MichaelKitces, my Tuesday 1 PM EST broadcast via Periscope, we discuss this phenomenon, called the Dunning-Kruger Effect, how it manifests itself (particularly for financial advisors with a few years of experience as they earn their CFP certification), and specific steps advisors can take to ameliorate feelings of inadequacy and (re)gain the confidence needed to serve clients effectively.

The first, and probably most important, step in dealing with the Dunning-Kruger effect is to realize that, simply by gaining some financial planning knowledge – much less earning CFP certification – you really are already far ahead of the knowledge curve relative to virtually every client or prospect you’ll ever meet, with more than enough expertise to add real value to clients.

Second is understanding that there’s nothing wrong with double-checking your work anyway – just to be safe – or even asking for a second opinion from more experienced advisors. Similarly, there’s absolutely nothing wrong with telling a client that you need more time to research a complex topic before providing an answer, just to be certain you really have considered all the issues.

From there, the best way to overcome the Dunning-Kruger effect is simply furthering your education by obtaining additional certifications and become a truly confident expert, establish a niche or mini-specialization that makes it easier to achieve mastery by narrowing the required scope of expertise in the first place, and focus on succeeding with clients who have less-complex financial circumstances before moving up the proverbial food chain of more affluent clients. Of course, it’s also helpful to simply stay flexible with the advice you give to clients in the first place… managing expectations to make it clear that the future can and will change, and that decisions don’t need to be viewed as irrevocable in the first place (because most aren’t!).

The bottom line, though, is simply to understand that you aren’t as ignorant as you may feel with the realization that there is so much to learn and consider in giving advice to clients, and that by taking steps to further your skills and knowledge, you can actively deal with the Dunning-Kruger effect and be the confident professional your clients are looking for.

(Michael’s Note: The video below was recorded using Periscope, and announced via Twitter. If you want to participate in the next #OfficeHours live, please download the Periscope app on your mobile device, and follow @MichaelKitces on Twitter, so you get the announcement when the broadcast is starting, at/around 1PM EST every Tuesday! You can also submit your question in advance through our Contact page!)

#OfficeHours with @MichaelKitces Video Transcript

Well, welcome, everyone. Welcome to Office Hours with Michael Kitces.

For today's Office Hours, I want to talk about a common challenge I see, particularly amongst up-and-coming advisors. The phenomenon that, despite having maybe gained your CFP certification and gotten a few years of experience and are able to add tremendous value and are getting ready to start moving up the line to take on more client responsibilities, you get stuck, afraid sometimes to actually take the leap to become a lead financial advisor.

And a good case in point example of this is a recent inquiry I got from Andy, who said, and I'm quoting or slightly paraphrasing his email here:

"Dear Michael, I'm an associate financial planner who's been in the industry for three years now, coming straight out of college, about to finish getting my CFP marks." Congratulations, Andy. "I'm coming to the point where I've developed a foundation of knowledge in all the financial planning topics, and it's time to begin making recommendations to help our clients, and I'm nervous about this. I have two knowledgeable advisors that will oversee my work, but at some point, I will be responsible for taking the lead on client relationships, and I fear missing something and putting a client at a disadvantage. At what point in your career did you become confident enough that you were able to give great advice and recommendations to your clients? And did you ever fear that your advice might backfire someday, like telling a client they're ready to retire and then the client comes back years later having run out of money?"

This is a great question, Andy, and one that really actually strikes home for me personally. So as many of you know from my own interview on our "Financial Advisor Success" podcast, I similarly started out in the industry straight out of college, but I wasn't a financial planning major. I was a psychology major, theater minor, pre-med student who basically only figured out by the end of college that I did not want to do psychology, theater, or medicine after I graduated. So I landed in the industry just because I needed a job and being a financial advisor sounded neat. So I got trained in the products that our company made available and went out there to get clients and to sell our products. And I was a good student, so I learned our products really well and I felt pretty confident that if any client asked me a question about our products and how they worked, I could answer that question. I knew my stuff.

But soon I realized that clients often have a lot more questions about our products than just what we were selling. And I was a financial advisor, it's what's on my business card, so they wanted to ask me financial advising questions, except I then quickly became aware that I didn't actually know anything about being a financial advisor. I didn't have a financial planning degree. I didn't have a finance degree. I only took one econ class in my entire college career and had a couple of weeks of product training. And it made me really self-conscious and fearful about the fact that I was giving people advice about their finances, in some cases about their entire life savings, and a lot of the time I didn't even know as much as my clients knew. At least they had, like, 10 or 20 or 30 years of life experience being a financial adult. I was a 23-year-old with no education and 5 months of experience.

And for me, that's what actually led me to go get my CFP certification, because I wanted to make sure I actually knew what the heck I was talking about when I gave my clients advice so that I didn't screw them up and unwittingly harm them. Except when I took my CFP classes and learned all the stuff in the curriculum, my fears got worse. Initially, I thought there was a lot I didn't know, then I went and got my CFP certification and realized there was really a lot I didn't know. There were things I didn't even know that I didn't know about until I learned a bunch of the rules and then realized how much more there was that I still didn't know about and that I could screw up with clients. And it actually made my confidence problem worse. At least initially, I had some level of blind ignorance that shored up my confidence - at least I knew my products and I didn't know what else there was to know - and then the more educated I got, the more I really realized how much I could screw a client up by getting stuff wrong, and it freaked me out.

The Dunning-Kruger Effect For Financial Advisors [4:09]

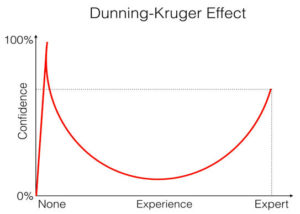

This phenomenon is not unique to financial advisors, though, it's actually a well-researched psychological bias. It's called the Dunning-Kruger effect. And the essence of the Dunning-Kruger effect is that, if you imagine like a graph with your experience level across the bottom and your confidence and your abilities going up, initially when we first learn something, we feel pretty good. Like, our confidence level shoots up. But then as we keep learning more and getting more experienced, our confidence level actually starts to come down. The more we learn, the more we realize what we didn't actually know initially, and the lower our confidence gets.

This phenomenon is not unique to financial advisors, though, it's actually a well-researched psychological bias. It's called the Dunning-Kruger effect. And the essence of the Dunning-Kruger effect is that, if you imagine like a graph with your experience level across the bottom and your confidence and your abilities going up, initially when we first learn something, we feel pretty good. Like, our confidence level shoots up. But then as we keep learning more and getting more experienced, our confidence level actually starts to come down. The more we learn, the more we realize what we didn't actually know initially, and the lower our confidence gets.

And it's only after this long valley of reduced confidence that we gain and learn more experience and knowledge. And then finally, true expert status shows up, where our confidence level shoots up again at the end. And now at least you either know your stuff, or if you don't, you know exactly where the limits to your knowledge are and where you need to collaborate with other experts.

But again, what the Dunning-Kruger effect shows is that it's actually normal that, after an initial spike in confidence when we learn, the more we learn from there, the less confidence we get. It declines as we gain experience and learn and then only very slowly recovers and moves back again as we become experts once we really, really learn our stuff. And what that means as an advisor (and I think as Andy highlighted in his question earlier) is that the exact moment when you're getting CFP certification and a solid baseline level of expertise tends, ironically, to be the point where you've never known more than you do today and you never feel less confident than you do at that moment. Because even though you know way more than you did before, you also realize how much you now don't know, and it becomes even harder sometimes to step up to a lead advisor role and take on more responsibility, even though your knowledge is there, because your confidence is not where it needs to be.

6 Ways To Overcome Dunning Kruger To Build Your Confidence As An Expert Financial Advisor [6:01]

So what can advisors do, particularly up-and-coming advisors - although this phenomenon is more widespread than just those of us who are newer to the business - what can you do to overcome the Dunning-Kruger effect and this crisis of confidence that can come, where the more expertise we get, the worse our confidence is and our ability to deliver value to clients?

1. Recognize What You Know

So first and foremost, recognize how much you actually do know. The irony of the Dunning-Kruger effect is that the moment that you feel the least confident in what you know is actually the point where you already know more than 99% of consumers. There are only 80,000 CFP certificants out there. There are 325 million Americans, so you're literally already 1 in 4,000 or about 0.025% of the population that knows as much as you do. Don't discredit your own expertise. Yes, there is this curse of knowledge thing that the more you know, the more you realize you don't know, and that's scary, but it doesn't change the fact that you still know way more than virtually anybody you are ever going to sit across from as a client. And don't underestimate how much value you can add just by talking about what you confidently do know. You don't have to push the great limits of your knowledge. Just help clients with what you already know you know... and move forward from there.

2. Double-Check Your Work And/Or Ask For Help

The second thing is there's nothing wrong with double-checking your work or asking for help. One of the key things that distinguishes real expertise from fake expertise is precisely that real experts know both what they know and what they don't know, and when it's time to bring in someone else to fill in the gaps. And there's nothing wrong with that. You don't think less of your doctor because he refers you to a specialist when you have a specialized problem. Instead, you value your doctor more for helping you find the right expert for the specialized problem that you're facing.

And the same is true of us when we work with our clients. You don't have to know everything about everything. You should be able to help them find their way to an answer. And that may involve bringing in another expert or referring out to another expert or simply taking a little more time to do your own homework and make sure you really know the answer. You can always say in a meeting when a client asks a hard question, "You know what? That's a really complex issue. Let me research that and I'll get back to you next week with an answer because I want to be certain I give you the right answer." Now, if it's a really simple question, clients do expect that you know the answer on the spot, but if it's a genuinely complex issue, clients generally don't have a problem with you researching and getting back to them in a timely manner, as long as you really do research it and get back to them in a timely manner.

Do you ever notice how often attorneys and accountants say, "I need to research that"? We don't think of them as unprofessional or non-experts just because they say they need to research a complex issue. To the contrary, we value them because the problem may be so complex that we need an expert with their depth to research it just to make sure they get the right answer. And the same applies to you as an advisor. So whether you need to ask the client for time to research the answer or go online to the FPA or NAPFA forums and ask the question of your peers or contact members in your study group, or reach out to a trusted planning colleague, or ask a fellow advisor in your office, or ask a senior advisor you work under or someone else, there's no shame in asking for help on complex issues to make sure you consider all the angles. That's what diligent professionals do.

3. Keep Your Advice Flexible

My third suggestion for those who are afraid about the consequences of locking a client into a bad recommendation that doesn't turn out well is, try not to lock clients into bad recommendations that don't turn out well. This indirectly is why helping clients stay "flexible" is so valuable. Yeah, some decisions like when to retire are bigger than others, but very few decisions that clients make are truly irrevocable unless you make it so as the advisor. So they're retiring but okay, perhaps they can go back to work part-time if they need to, or they can manage their spending down for a few years if they hit a speed bump, or they can downsize their home or get a reverse mortgage line of credit as a reserve. There are lots of strategies that we can put in place.

This is actually mostly about managing client expectations. If you say to clients, "I recommend that you retire now because we've done our analysis and you will never need to work again or have any other need or care in the world because you have more than enough money to last you forever," well, and I sure as heck hope that you're right because you just made that sound pretty permanent and irrevocable. But what you say to clients is, "Our analysis indicates that you have enough to retire. And while we can't guarantee anything in this world, even if a problematic sequence of returns appears, we have a lot of ways to manage this risk, including modest spending cuts just to get you back on track or possibly doing that part-time consulting work you were talking about doing anyways, or downsizing your home. You already mentioned maybe buying a condo close to your grandchildren anyways and we could free up a little bit of capital with that."

You're here to give your best advice. You're not giving life guarantees in a world where life just isn't guaranteed. And as long as you keep your advice flexible - so watch out for recommendations that have lots of debt, low liquidity, and other irrevocable constraints that reduce choice and flexibility - as long as you keep advice flexible and you reasonably manage expectations, you and your clients can adjust if necessary. I mean, most people don't just spend like lemmings until one day they walk off the cliff and find out they're broke and nothing is left. We can make mid-course adjustments as long as you set your clients up to understand, "We're here to give you our best recommendations, and we're here to help you along the way if something changes."

4. Reinvest Further In Your Education

Fourth, if you really want to overcome the Dunning-Kruger effect from a technical perspective, keep pushing through that experience and education curve. Keep learning. Keep reinvesting in your knowledge and education. Because the Dunning-Kruger effect shows a decline in our confidence as we learn more, and then eventually an increase in our confidence as we approach mastery and expertise.

Frankly, as many of you know, I increasingly view CFP certification, not as the endpoint for getting your financial advisor marks to be successful, but the starting point. And once you get your CFP certification, you can pursue what I call post-CFP designations or specializations that take your expertise even further. That might be a master's degree in financial planning or a specialized retirement certification like RICP (Retirement Income Certified Professional) or RMA (Retirement Management Analyst) , or deeper investment expertise with CIMA (Certified Investment Management Analyst) certification, or more insurance knowledge with the CLU (Chartered Life Underwriter) designation, or a more niche specialization like the CDFA (Certified Divorce Financial Analyst) designation for working with divorcées.

This is why I personally have such an alphabet soup of degrees and designations after my name. When I finished CFP certification, I just stayed enrolled. One course per term. Nothing too intensive because I was working full-time building my career as an advisor as well. But staying continuously enrolled for an extended period of time adds up to a lot of education and expertise over time and brings a lot of confidence over time. Just as we tell clients, "The key to long-term financial success is not playing the lottery and winning, it's saving a little every month and letting it compound." And the key to long-term expertise and confidence is to learn a little bit every month and to let it compound. And the deeper your knowledge goes, the more confidence you'll build as you get through the low point of the Dunning-Kruger effect and begin to build and grow from there.

5. Narrow The Scope Of Required Expertise With A Niche Or Specialization

Fifth, one of the easiest ways to get more confident in the knowledge you have is to narrow the scope of what you advise on in the first place. In other words, the more niche or specialized you get, the less you need to know about everything, and the easier it is to become a real expert that really does know everything there is to know about the specific issues of your niche or specialization.

We had a recent guest post on the blog from Meg Bartelt, who has a niche in serving women in technology firms, and how it became a lot easier for her to get up to speed on the new Tax Cuts and Jobs Act legislation from last December because she didn't need to learn everything about the legislation in that lovely 8,000-word article we wrote, she just skipped to the few points that were relevant for her clients, and then she learned those sections inside out. And that's often, I think, one of the undiscussed benefits of having niches and specializations. While by definition it means you have to go deeper in that area than anybody else, it actually makes the challenge of becoming an expert easier because it really is easy to know everything when you limit the domain of what you need to know in the first place and just go deep.

As a starting point, you can adopt a mini-specialization even in your own firm. Become the go-to expert on RMD rules for your clients or a particular investment product or strategy. My mini-specialization the first three years of my career was to be an expert in the new generation of variable annuities with living benefit riders that were coming out at the time in the early 2000s. It got me a lot of expertise. It got me a lot of experience. It eventually led to me publishing my first book. And in the end, it didn't actually take that long to learn. I didn't know everything about retirement or even about all types of annuities at the time, but I became an expert in variable annuities with living benefit riders because I focused there and I just read every single contract there was and learned everything I could about them. So if you're feeling overwhelmed by the weight of how much there is to learn and advise on, don't try to learn and advise on so much at once. Get more focused on something you really can master. Be awesome at that. Get really confident with your expertise there, and then add the depth and breadth over time.

As a starting point, you can adopt a mini-specialization even in your own firm. Become the go-to expert on RMD rules for your clients or a particular investment product or strategy. My mini-specialization the first three years of my career was to be an expert in the new generation of variable annuities with living benefit riders that were coming out at the time in the early 2000s. It got me a lot of expertise. It got me a lot of experience. It eventually led to me publishing my first book. And in the end, it didn't actually take that long to learn. I didn't know everything about retirement or even about all types of annuities at the time, but I became an expert in variable annuities with living benefit riders because I focused there and I just read every single contract there was and learned everything I could about them. So if you're feeling overwhelmed by the weight of how much there is to learn and advise on, don't try to learn and advise on so much at once. Get more focused on something you really can master. Be awesome at that. Get really confident with your expertise there, and then add the depth and breadth over time.

6. Succeed With “Simple” Clients And Work Your Way Up

And this, in turn, leads me to my sixth and final piece of advice, particularly for up-and-coming advisors who are struggling with their confidence as they realize that maybe you don't know how much you realize you need to know and are nervous about serving clients well. Try to find some opportunities for what I'll call small wins first. You don't have to make your first clients the most comprehensive ever of comprehensive financial planning clients with the most complex situations. Try to work with simpler clients that have more straightforward problems first. The kind you really are confident you can solve effectively. And as you gain expertise and do some good work with clients that have simpler situations, you can move up to working with more complex clients.

I know some advisors that don't like this. They say it feels belittling or demeaning to work with the smaller clients of the firm before moving up to the bigger clients. And that it feels like you're being forced to pay your dues. But the reality is that putting in time to get experience with simpler clients is the crucial step to building your confidence and your expertise and your experience to be able to serve more complex clients. In other words, paying your dues really is an important step in the process in building your confidence and knowledge and expertise by putting in the time that it takes.

The bottom line, though, is just to recognize the fear you may be feeling as an advisor as you get more knowledgeable and experienced and realize how complex this stuff actually is and how much a client can be damaged if something goes wrong is completely normal. It's a well-documented psychological bias, it's called the Dunning-Kruger effect, and you can work through it successfully. The biggest key at the end of the day, though, is just to be certain that you keep moving forward. The Dunning-Kruger effect means your confidence comes down, and then if you work through it, it comes up again. And the best way to get over your fears means getting more experience, more expertise. So reinvest in your own education. Focus on a niche or specialization. Just try to get more client-facing time to practice and get experience with simpler clients where you are confident that you can make the right recommendations. And remember, there's nothing wrong with asking for a little help, getting a second opinion from a colleague, or making a referral as well.

This is Office Hours with Michael Kitces. Hope it's helpful food for thought. Thank you for joining us, and have a great day, everyone.

Disclosure: Michael Kitces is a co-author of The Advisor's Guide to Annuities, which was mentioned in this article.

Leave a Reply