Executive Summary

The traditional path to growing an advisory firm – or any business – is fairly straightforward: craft a product or service that you can deliver profitably, and then deliver it profitably to more and more people. The greater the number of clients or customers who are paying for the solution, the more total revenue the business generates, and the more in profits that accrue to the owners (assuming a reasonable profit margin in the first place). In the early years in particular, when a financial advisor still has a lot of capacity (i.e., time) and not a lot of clients, adding more clients and the revenue they bring can quickly ramp up the income of the financial advisor themselves.

But only up to a point: the individual capacity of a financial advisor is typically no more than 100 clients in an ongoing advisory relationship. As once the advisor’s individual capacity is reached, the only way to continue to add more clients is to add more staff to service them, including another advisor to work with them. Which suddenly makes the next 100 clients not nearly as profitable to the advisor as the first 100 might have been.

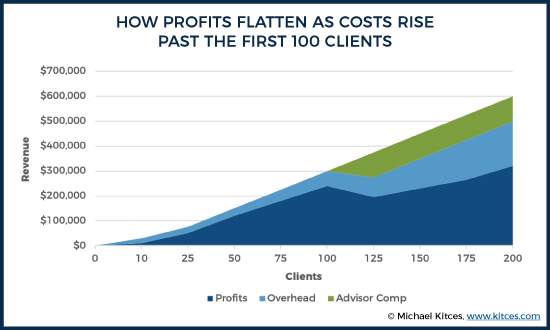

Because the reality is that for a financial advisor’s first 100 clients, the advisor is actually paid in two ways: part of the revenue compensates the advisor for the work he/she does in the business, while the (smaller) remainder is compensation as profits for being the owner of a successful advisory business. While for the next 100 clients, the next advisor is paid for doing the advisory work in the business, while the advisory firm owner is “only” compensated with the profits of growing the business larger. Which means in practice that an advisory firm owner might take home 70% to 80% of the revenue from the first 100 clients in combined profits… but only 20% to 30% of the revenue for the next 100!

Of course, continuing to grow an advisory firm, and participate in the profits, is still a goal of the business (and the income of the owner), for those who have a goal to grow further. But it also means that for many advisors, it may actually be far easier and more efficient to grow not by adding another 100 clients, but trying to replace the existing 100 clients with others who are more affluent and can pay higher fees. Effectively generating more revenue for the firm not from more clients in total, but revenue per client instead. All of which drops to the bottom line take-home pay of an advisor-owner with fixed overhead costs.

At a minimum, though, the key point is simply to recognize that what it takes to generate more income, once an advisor reaches capacity, is very different depending on whether the advisor tries to grow a larger business with more clients, or simply via more revenue from each client. Not that there is necessarily a “right” or “wrong” path, but growing the firm with more clients does mean added staff, overhead, and risk, in an effort to grow a larger business with less incremental profit that comes with it. Which means if advisors are going to go the path of growth through more clients, it should at least be done with eyes wide open… and an awareness that there are (potentially more efficient) alternatives to growth instead!

The (Profitable) Path To Client Capacity

The challenge for financial advisors when getting started is that there’s a lot of time, but not so many clients to service. From the business’ perspective, the practice has a lot of “excess capacity”… ready and willing and able to serve the clients it hasn’t even gotten yet. For the end advisor, this usually means having negative income, given that there are at least some overhead costs to running the business – from compliance to having a website to the core tech the advisor needs – but not enough revenue (yet) to cover the costs.

Of course, as clients do begin to show up, the revenue of the advisory firm rises, and cash flow breaks even and then turns positive. Because most of the overhead expenses to start the practice are fixed and/or already sunk costs, every marginal new dollar of revenue at the top line drops directly to become part of the bottom-line profits – i.e., the take-home pay – for the advisor.

Thus, the most direct path for the typical financial advisor to generate more income is very straightforward: just go get more clients to bring in more revenue (over and above the firm’s overhead expenses). And the approach works quite well; it’s not uncommon for solo advisory firms to take home nearly $0.70 for each dollar of revenue, and the most profitable solo advisory firms take home as much as 85% of their revenue. In real dollar terms, an advisor with 70 clients generating $200,000/year of revenue might take home nearly $140,000 of it, while an advisor who grows to 100 clients and $300,000/year of revenue would typically keep anywhere from $210,000 to $250,000 in profits. Notably, though, from the perspective of take-home income, the bigger driver of net income to the advisor is not actually the firm’s profit margin; it’s the total number of clients, and the revenue they generate for the firm, that’s dropping straight to the bottom line (because the overhead costs tend to be largely fixed).

The caveat, however, is that this formula – “keep adding clients that generate top-line revenue that flows straight to the bottom line of the advisor’s income” – only works up until a point. And that point is the maximum capacity of an individual financial advisor to service those client relationships. In other words, a single financial advisor can only add "so many” clients, until there just isn’t any more time to service more clients.

After all, if the financial advisor is going to meet with clients at least twice a year – which necessitates as much as 4 hours of meeting time, plus often another 2 hours of prep time – and then has to field another 4 hours’ worth of emails and phone calls that lead to ad-hoc research and analysis to answer planning questions, plus 4 hours of miscellaneous service time (for trading, rebalancing, and other investment management duties), it adds up to 14 hours per client. Which at 100 clients, would already consume 1,400 of the available 2,000 working hours in a year. And at that point, it takes most of the other 30% of the advisor’s time just to handle the rest of the administrative and management tasks of the firm, compliance duties, and professional development of the firm. Not to mention the time it takes to prospect and market to get new clients as well. In fact, recent research shows that advisors on average spend only 60% of their time on direct client-facing and investment management tasks throughout the year!

Not to mention that research also suggests that our brains themselves are limited in the total number of relationships that we can handle. Known as Dunbar’s Number, the data suggest that physiologically, the human brain may not be able to handle more than 150 total relationships with other human beings. And given that a chunk of those available relationship slots will typically be "used up" by existing friends and family already, most financial advisors may not have more than 100 "brain slots” left anyway! In other words, even if the advisor had more time to service more clients, it’s not clear that they’d simply be able to keep track of who’s who in their heads (or even with the support of good advisor CRM), undermining the ability to maintain effective relationships with them anyway.

The key point, though, is simply that at some point, every financial advisor hits his/her personal capacity of how many clients can be served, beyond which is no longer able to grow by just adding clients. At least without making more significant changes to the firm. And that capacity point appears to be right around 100 ongoing clients in financial planning relationships.

The Economics Of Growth: Why The Second 100 Clients Are Not As Profitable As The First

The virtue of the solo advisor model is that, because the overhead (and especially staffing) costs of the business are so low (and generally fixed), “most” of the new revenue from the next new client goes directly from top-line revenue to bottom-line profits and take-home pay of the advisor. Which is what makes it possible to have businesses where the solo advisor takes home profits as high as 85% of revenues.

But the truth is that even the high-margin solo advisory firm isn’t truly running an 85% profit margin. Because a large portion of the financial advisor’s compensation is actually for the work in the business, not just the profits of the business.

Historically, this was embodied by the “40/35/25” rule of advisory firms: that 40% of revenue goes to the “Direct Costs” of servicing clients, including the financial advisors to deliver planning services, and the investment team to manage the portfolio (if applicable); 35% of revenue goes to the overhead costs of the business, from rent and technology expenses to compliance and administrative staff costs; and that leaves 25% of revenues as a net profit margin for the advisory firm business owner.

Historically, this was embodied by the “40/35/25” rule of advisory firms: that 40% of revenue goes to the “Direct Costs” of servicing clients, including the financial advisors to deliver planning services, and the investment team to manage the portfolio (if applicable); 35% of revenue goes to the overhead costs of the business, from rent and technology expenses to compliance and administrative staff costs; and that leaves 25% of revenues as a net profit margin for the advisory firm business owner.

Of course, for a solo advisory firm has very limited infrastructure and overhead needs, it may be feasible to run with as little as 15%-25% overhead, leaving the formula more akin to 40/15/45 or perhaps 40/25/35, and a combined take-home pay as high as 75% to 85%, between the first 40% for the advisor’s work in the business doing financial planning and investments, plus the remaining 35% to 45% of bottom-line profits.

Except, as noted above, that the solo advisor eventually hits personal capacity. Which means after the first 100 clients, the only way to add the next 100 clients is to hire another associate or even lead advisor to service those clients. And that’s when the economics of growth begin to change for the owner-advisor.

Because the next advisor who joins – and ostensibly is not an owner in the firm – will simply want to be paid what he/she is worth, off the top, as a direct cost of the business. Which suddenly means that 30% to 40% of the next 100 clients’ worth of revenue doesn’t accrue to the owner. It’s paid to the next advisor who services them, instead.

In addition, adding another advisor to the firm begins to add more demands for the overhead infrastructure of the advisory firm. Growing from 100 to 200 advisors often requires more administrative infrastructure. There may now be a full-time client service manager. And an administrative assistant to support the two advisors. And potentially someone to just handle the trading and support the investment research or paraplanning analyses. Which in turn may require new/more office space. And additional technology licenses. And more compliance support. Which means it’s no longer feasible to run the advisory firm with only 15% overhead. Now the overhead costs rise to 25% to 30% instead, as the firm’s formal infrastructure (at industry-standard overhead expense ratios) starts to take shape.

The end result is that not only does the advisory firm owner “only” participate in the bottom-line profits of the next 100 clients, and not the compensation for advising, but the next 100 clients – and the advisor and support staff to service them – typically increases the overhead costs of the firm as well. Which means the advisor participates in even less of the revenue for the next 100 clients.

Thus, while the financial advisor might have had $300,000 of revenue (e.g., $3,000 revenue/client x 100 clients) originally, and enjoyed an 80% profit margin and $240,000 of take-home revenue, with the addition of the next 100 clients, the firm grows to $600,000 of revenue (doubling the clients to double the revenue), but the next advisor would need to be paid at least $100,000 to service that $300,000 of client revenue. And the firm’s overhead costs may rise to 30% x $600,000 = $180,000, as two more full-time staff members are hired to support the breadth of 200 clients. Such that the firm owner’s net profits rise “just” $80,000 (from $240,000 to $320,000, or a 25% increase in take-home pay)

Notably, the end point of the above example is that the advisor has added far more in complexity to the advisor-owner’s life, as the firm may well shift from “just” the advisor and an assistant or paraplanner, to a team of 5 (including 2 advisors and 3 support staff). Which in turn requires an increase in time allocated by the advisor to the management of the firm as well. For which, even after doubling the firm’s revenue – a 100% increase in clients and the fees they pay – the advisor gets “only” a 25% increase in his/her own compensation.

In other words, growing past an advisor’s individual capacity is the opposite of growing to gain economies of scale (at least in the near term). Instead, the transition from 100 to 200 clients tends to undermine economies of scale, and requires a substantial level of reinvestment into the business and infrastructure building. To the point that the advisor’s income may initially go backwards, and only as the second advisor themselves approaches capacity, finally turn positive again. And by then, the advisor is still “only” up 25% in profits, despite doubling revenue and more-than-doubling staff headcount and complexity!

Ultimately, though, that’s the whole point of the shift from getting paid for the clients that the advisor takes on themselves (as the advisor-owner), to getting profits by adding more clients to the business (as the owner who employs other advisors servicing those clients). The path to 100 clients compensates the advisor for both the clients themselves and the profits of the firm, while the next 100 clients "only" compensates the advisor with the profits of the business (at a cost of investing into infrastructure and complexity along the way).

The Easiest Path To Higher Income Is “Bigger” Clients, Not More Of Them

As the owner of any business – including an advisory business – growing revenue for an otherwise profitable firm is an effective way to generate more income for the other. Even if there isn’t much of an opportunity to gain economies of scale – where overhead decreases and profit margins improve with size – there is still at least the opportunity to just make the profits on a larger revenue base in the first place. A 25% profit margin on $1M of revenue is still more than a 25% profit margin on only $500,000.

The caveat, however, is that it’s not necessarily an easy path, and it’s one where – for financial advisory firms in particular – the second 100 (and subsequent clients thereafter) lift the advisor’s income far less than the path to the first 100 clients. Because the advisor now only participates in the profitability of the firm, and not the financially lucrative rewards of “doing” the financial advising in the first place (which is the driver of the advisor’s compensation for the first 100 clients).

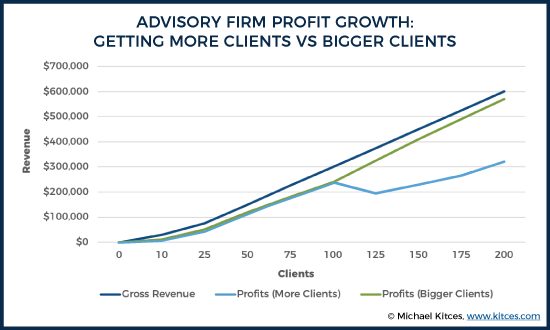

All of which is important, because it actually means that for most advisors, the easiest and best path forward for those who actually do want to increase their financial rewards of doing financial advising is not to grow revenue bigger by getting more clients. It’s to grow revenue bigger by getting bigger (i.e., more affluent) clients to slowly but steadily replace the ones the firm already has.

In other words, the central driver for income growth for most advisory firms is not just growing total revenue (and the profits thereof) by adding more clients, but specifically by increasing revenue through an increase in revenue per client. Which increases the amount of revenue that the original/founding/solo advisor can generate given a maximum capacity of 100 clients (or less), without adding overhead and other staffing costs.

After all, an advisor who moves upmarket, and tries to focus on fewer but more affluent clients, and ends out with 'just' 50 Great Clients paying $12,000/year, generates double the revenue of serving 100 clients at $3,000/year. But rather than seeing “only” a 25% increase in take-home pay for the advisor (from $240,000 to $320,000) by doubling the firm’s revenue, working with fewer more affluent clients causes the advisor’s take-home pay to potentially double... or even better, as all of the additional revenue drops to the bottom line. And reducing from 100 to “just” 50 clients may even reduce the advisor’s overhead costs (and further improve the firm’s profit margins) because there are fewer clients to service in the first place!

In point of fact, this is likely why it’s already so often the case that advisory firms tend to move “upmarket” as they grow, seeking out and working with more affluent clients, and establishing or increasing their asset or minimums. Because, again, increasing revenue per client is an "easier" way to grow an advisor’s income than increasing total clients and revenue. Since it doesn’t require hiring more staff, or – more importantly for many advisors – doesn’t require adding more management complexity to the business (given that many advisors started their firms to serve their clients, not to manage a growing number of people!). Not to mention that for advisors who are approaching capacity, and must decide what to do next, a decision to move “upmarket” coincides well with the advisor’s own growing level of credibility and community connections that make it feasible to generate more affluent business opportunities or referrals.

The key point, though, is simply to know as a financial advisor what you want to build, and why. And recognize that just adding more clients – past the first 100 or so, which is generally the individual advisor/owner’s capacity – isn’t necessarily going to generate (much) more income, but will potentially generate a lot more work and complexity for the firm. Which is a fine challenge to work through for those whose vision is to be an entrepreneur that grows and scales a large advisory firm far beyond themselves. But it is also important to recognize in advance and be prepared for. Otherwise, the advisor risks becoming an “accidental” (and accidentally very unhappy) advisory firm owner, simply trying to "grow" the business and ending out managing a substantial number of staff members and complexity instead of simply doing (more of) the client work they enjoyed in the first place.

Which means for most advisors, who simply may want to "grow a little more" and have some potential for additional income and upside – but without the complexity of hiring and adding staff – continuing to grow the total number of clients is perhaps counterintuitively not the best path forward. Because the reality is that the next 100 clients are simply never as profitable for a financial advisor (and advisory firm owner and founder) as the first 100. Instead, the most straightforward path to growth is not adding another 100 clients, but increasing the revenue/client for the clients the advisor already serves. Which sometimes means replacing some or many of the clients the advisor has today. (Fortunately, though, there’s always another advisor out there for whom your “no-longer-cost-effective” clients are still incredibly valuable!)