Executive Summary

For years, industry commentators have been anticipating an “onslaught” of retiring baby boomer advisors who will begin to engage in succession planning en masse and sell their firms over the next decade. Yet year after year, the baby boomers get older, and the sellers don’t materialize; with an astonishing paucity of sellers to external buyers and an abundance of buyers, it remains a seller’s market for financial advisory firms.

Yet in a new book, David Grau (founder of FP Transitions, a firm that has potentially already been involved with more advisory firm sales than any other consultant or service provider in the industry today) makes the compelling case that for advisors to be focused on big headline external sales to third parties misses the real opportunity – an internal succession plan executed over a period of years or even a full decade, that ultimately delivers radically more to the founder than a third-party external sale ever could.

In order to harvest the greater long-term value from an effective succession plan, though, Grau points out that advisory firms are still too attached to the wirehouse-style “eat what you kill” revenue-based compensation, that simultaneously destroys value for the business owner and disincentivizes the next generation of owners from wanting to be successors in the first place. Instead, Grau suggests that firms need to shift from compensation based on top-line revenue to a greater focus on compensation built around bottom-line profits, that can ultimately help to both focus the business on maximizing its value, and truly incentivize the next generation of advisor owners to want to step up, buy in, and contribute towards – and be rewarded for – enhancing that long-term value.

Selling Or Exiting An Advisory Business Versus True Succession Planning

Most professional services businesses aren’t really businesses, because they’re not built to survive as a business beyond the founder that creates it. It’s no coincidence that from doctors to dentists to many lawyers, the “business” wrapped around the practitioner is not actually called a business, but a “practice” instead. A practice might ultimately still be sold to another practitioner, but ultimately the only thing that really transitions is a list of clients/customers/patients, and perhaps a little ongoing revenue attached to them. The original business itself generally does not survive.

Accordingly, in his new book “Succession Planning for Financial Advisors”, David Grau Sr. points out that most advisory firms are also, ultimately, little more than practices that might generate some very positive cash flow for the practitioner, but are not structure to survive the founder’s death, disability, or retirement. Again, a client list might be sold, and the advisor might exit with some lingering value, but the business itself will not survive as an ongoing business.

Accordingly, in his new book “Succession Planning for Financial Advisors”, David Grau Sr. points out that most advisory firms are also, ultimately, little more than practices that might generate some very positive cash flow for the practitioner, but are not structure to survive the founder’s death, disability, or retirement. Again, a client list might be sold, and the advisor might exit with some lingering value, but the business itself will not survive as an ongoing business.

By contrast, a true succession plan – at least, according to Grau – is one that does allow the business to continue and survive intact. In fact, Grau’s definition of a true succession plan implicitly assumes that for a business to continue, the continuity must come within:

A succession plan is best defined as a professional, written plan designed to build on top of an existing practice or business and to seamlessly and gradually transition ownership and leadership internally to the next generation of advisors.

When elevated to this standard, arguably there is remarkably little succession planning really happening in the financial services industry today. Grau estimates that as few as 1% of firms are prepared and positioned to execute on a real succession plan, and that as many as 99%(!) of today’s independent advisory firms will not survive beyond their founder, either simply attritioning to the point of worthlessness as the advisor’s career winds down, or perhaps with a list of clients being sold for some terminal value but without the survival of the business itself.

Notably, Grau acknowledges that for many advisors, they may not want to leave the business in the first place. Many (most?) financial advisor entrepreneurs are not hard wired to sell and exit their practices, as much of both their financial net worth and personal intrinsic reward are tied up in the relationships with their clients. Nonetheless, even if there’s not a desire to sell and exit the business for personal reasons, Grau makes a compelling case – and increasingly, so are regulators – that the continuity of the business as a business is crucial if only to ensure a continuity of care for the clients. Yet for an advisory practice to effectively function as a business upon which a succession plan can be executed, it’s first crucial to structure it like a business in the first place…

The Business Problem With Advisor Compensation Based On Revenue Sharing

Amongst today’s experienced financial advisors looking to sell their independent advisory firms, it’s almost impossible not to find someone who either started their career in a wirehouse, or were trained by someone who was. As a result, almost all of today’s independent advisory firms continue to structure their compensation in the manner of a wirehouse: compensation tied directly to top-line revenue, often accompanied by an implicit “Eat What You Kill” (EWYK) (and don’t eat from what you didn’t kill) mentality. In the context of a wirehouse – where advisors don’t ultimately own their underlying business anyway – this is a fine compensation structure, but in an independent advisory firm, Grau makes a compelling case that it is ultimately highest destructive of both the value of the business and the ability to craft a succession plan.

The key problem with an eat-what-you-kill style of compensation in an independent advisory firm is that it ultimately provides too much of the long-run rewards of ownership to advisors, without the associated long-run risks. In the early years, the burden of risk in an eat-what-you-kill environment is on the advisor; after all, if the advisor doesn’t “kill” anything (get their own clients), there’s no revenue to be paid upon, and as we know, the attrition rate for new financial advisors is very high. However, once the advisor eventually does accumulate a base of clients with ongoing revenue, the tables turn; now servicing clients is easier, there’s little or no pressure to grow, yet the advisor has no responsibility for managing the ongoing risks and challenges of the business itself, from hiring to technology to office leases and more. And what advisor wants to “buy in” to an advisory practice for which they’ve already borne the upfront risks in getting clients in the first place, and are now already reaping the rewards of a high income tied to their clients with little remaining risk!?

The solution, in Grau’s view, is to back away from our “traditional” wirehouse-based approach of tying compensation to revenue, and instead compensate advisors with a (healthy) salary plus (reasonable) incentive compensation for key results like retaining clients and bringing in new clients… but not tying that compensation directly to revenue (or targeting it based on revenue). The end goal of such an approach is to “flatten” compensation out across advisors, and shift the “excess” revenue from compensation to the advisor off-the-top (as a percentage of revenue) into compensation as a profits distribution from the bottom line.

The important distinction of this change is that now, there really is a financial incentive to be an owner – because reaching the highest levels of income requires access to salary for a job well done, and ownership of shares for a right to profit distributions. The mentality is no longer “why would I want to buy in what I just helped to build when I’m already getting paid such a great share of the business” and instead becomes “what do I have to do to help grow the value of this business so that I can have the opportunity to become an owner and have access to profits distributions for the value I’m creating?”

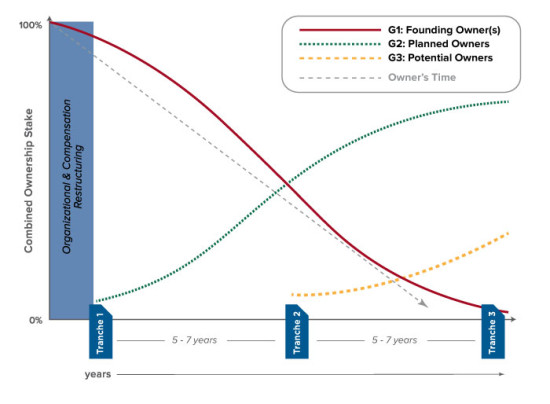

Not that Grau advocates that firm owners should immediately sell everything once this incentive is created; instead, ownership can be sold to younger generations in tranches over time, as shown in the graphic below. This allows the founders to witness whether/how the next generation of owners step up to the opportunity and whether they really do follow through in helping to build the value of the business. In fact, Grau finds that most of the time, if the next generation advisor sticks around for the entirety of the first tranche and still want more, they typically stay with the firm and help build it for the long run.

Maximizing Equity Value And Equity Management

Ultimately, Grau suggests that the transition away from revenue-based compensation and an increasing focus on not just the top line but also the bottom line of the advisory business is just one part of a broader shift towards actually managing the business as a business. Unfortunately, though, not a lot of advisors necessarily know how to manage an advisory business as such – as something broader than just their own contribution to the business – and many are unfamiliar with what aspects of the business drive the most value.

Accordingly, Grau advocates that advisory firms should consider an ongoing process of getting an annual valuation of the firm (notably, a service that his own FP Transitions firm provides), as seeing the factors that go into a valuation, and how they impact the value of the business, can itself be a highly effective guide for management about what steps to take to increase the value of the firm. After all, there’s nothing like seeing the annual valuation of the firm decline due to an aging client base, a lack of growth, overreliance on key staff members, or some other factor, to recognize that it’s a problem to fix.

In addition, an annual valuation process helps to focus everyone – including next generation minority owners – to understand exactly what is necessary to increase the long-term value of the business for everyone’s benefit. In other words, it’s a way of communicating and aligning the goals of all business owners, when they have a common point of understanding of what it takes to increase the value of their jointly-owned business: the annual valuation.

In turn, an understanding of the ongoing value of the business and how it can be shaped and enhanced also facilitates the use of the equity in the business as a tool to provide (buy-in) opportunities for the next generation and incentivize behavior – a process that Grau calls “equity management” where the equity of the firm itself is managed as an asset to be deployed for creating incentivizes. Not that equity should necessarily be given as compensation – in fact, Grau strongly advocates that most/all shares should be bought, and that once compensation is restructured (by moving away from revenue-based compensation) it will be desirable as an asset for purchase. The point is simply that deciding who should get access to equity, under what terms, and subject to what requirements to be eligible, is itself something that can be managed for the long-term health and success of the firm and its succession plan.

Succession Planning For Financial Advisors by David Grau

Overall, Grau’s book is an incredible read for anyone who wants to better understand how to really execute a succession plan, whether from the perspective of a firm owner considering the process now or in the future (Grau advocates that succession planning should begin for most firm owners in their early 50s or even earlier), or a next generation owner that wants to understand what’s involved (or perhaps even share some advice “up the line” to their firm’s founders).

Grau’s firm has been involved in valuating advisory firms, facilitating sales and exit planning, and consulting on succession planning, since 1999, and the experience of having been involved with so many advisors and firms over the years shows through clearly in the book, which just “oozes” with wisdom and perspective on what’s worked and what hasn’t. Other key points the book covers also include:

- The importance of the right entity structure to facilitate the transition (with some in-depth discussion of the benefits of LLCs versus S corporations)

- What Grau calls “the 30-hour workweek threshold” below which the founding advisor’s role within the firm begins to change in a significant way (and the importance of transitioning equity at a pace similar to the transition of the advisor’s time away from the firm)

- Why today’s dearth of talent with young advisors and the struggles that so many firms have in retaining talent may simply be because the younger advisors are correctly perceiving the lack of opportunity where they are now because most firms really don’t have an effective succession plan

- The importance of having multiple next generation owners to recognize that nothing is certain and that some young advisors really will not step up, so it’s important to diversify amongst successors. However, with effective equity management and a properly structured succession plan, far more young advisors will “step up” than the typical founder expects and realizes.

- Contrary to conventional wisdom, advisors who want to maximize the value of their practice are actually better served with an internal succession plan than an external sale, because the opportunity for a gradual internal transition actually allows the founder to continue to participate in the growth of the firm during the transition, leading to far more long-term value for the founder. An external sale should actually be a last sort for harvesting remaining value, not a first priority!

At times, Grau’s book does sometimes read like an advertisement for some of the services that FP Transitions provides, from consulting on succession plans to brokering of third-party sales to annual valuation services. But arguably, the book also makes it clear that Grau and his firm may have more “real deal” perspective than virtually any other consultant or supporting firm out there, and it’s hard to blame Grau for regularly citing his firm’s own data and solutions where there are virtually no alternatives available to advisors in the first place!

The bottom line, though, is simply this: there are few books out there that really do a comprehensive job covering key practice management issues for advisors, that contain both practical knowledge, advice substantiated by research and actual data, and the kind of insight that can only be garnered by real experience. The short list includes Tibergien and Dahl’s “How to Value, Buy, or Sell a Financial Advisory Practice”, Tibergien and Pomering’s “Practice Made (More) Perfect” and Philip Palaveev’s “The Ensemble Practice”. And now David Grau’s “Succession Planning for Financial Advisors” deserves to be added to the list as well!

The bottom line, though, is simply this: there are few books out there that really do a comprehensive job covering key practice management issues for advisors, that contain both practical knowledge, advice substantiated by research and actual data, and the kind of insight that can only be garnered by real experience. The short list includes Tibergien and Dahl’s “How to Value, Buy, or Sell a Financial Advisory Practice”, Tibergien and Pomering’s “Practice Made (More) Perfect” and Philip Palaveev’s “The Ensemble Practice”. And now David Grau’s “Succession Planning for Financial Advisors” deserves to be added to the list as well!

So whether you are an advisor thinking about executing a succession plan in the future, or potentially being part of someone else’s succession plan someday, I’d highly recommend picking up a copy!