Executive Summary

Despite decades of encouragement to save a percentage of annual income, the national savings rate has been in decline for decades, and a disturbing number of today’s 50-somethings are seeing their children off to college, only to turn to their own financial situation and realize there's a significant shortfall in retirement preparedness.

Yet given the reality that it’s very expensive to raise children – including the ballooning cost of college – arguably this transition into the empty nest phase provides a unique opportunity for households to play “catch-up” for retirement… simply by taking the money that was once being spent on the kids, and saving it instead!

In other words, perhaps the idea of saving a steady percentage of income throughout our working years was never a reasonable approach to begin with, and that a strategy more sensitive to the spending realities of the child-rearing versus empty-nest phases of accumulation is both more realistic, and what many households will end out doing anyway.

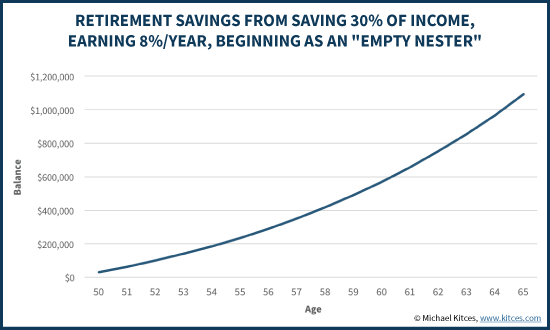

Which means the real key to retirement success may not be about saving early and often for the long term at all, and that instead a significant post-child-rearing-phase "catch up" sprint is the normal path to retirement success. In turn, this suggests that the most crucial phase of retirement saving is not figuring out how to save during the early working years, and instead is about ensuring that the transition into the empty nest phase is used as an opportunity to catch up on retirement savings – after all, just 15 years of saving 30% of income once the kids are out of the house is still enough for an astonishing number of households to stay on track for retirement!

The Traditional Save-A-Percentage-Of-Income Approach To Retirement

The traditional approach to retirement saving is relatively straightforward: save a percentage of your income every year to put towards your retirement. The longer the time period, the more it can grow and compound. The higher the percentage you save, the faster you’ll reach your retirement goal.

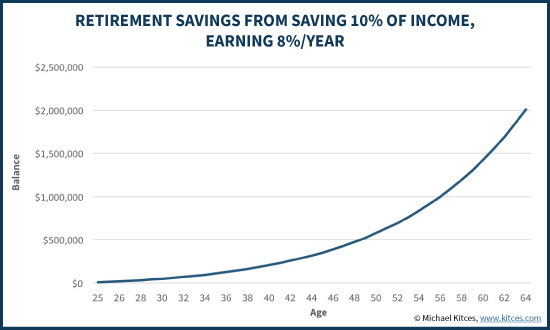

For instance, if you’re 25 and make $50,000/year and save 10% of your income, get 3%/year raises (for inflation) along the way, and save in a long-term aggressive growth portfolio that gets an 8% long-term rate of return, by the time you retire you’ll have a whopping $2,000,000 retirement portfolio!

Of course, an important caveat is that spending from a $2M portfolio won’t go nearly as far in 40 years, as even with just 3%/year inflation, the purchasing power of those distributions will be cut by nearly two-thirds! Nonetheless, even after adjusting for inflation, taking a 4% initial withdrawal rate from the portfolio, and supplementing with Social Security benefits, would allow you to maintain and fully replace your pre-retirement spending during your retirement years.

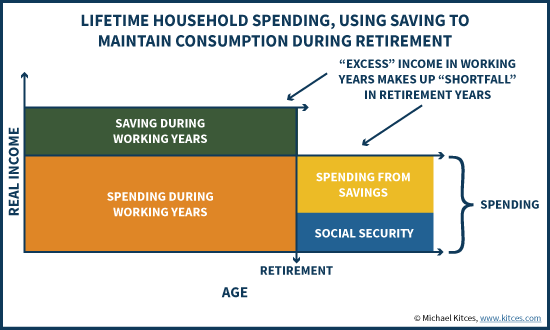

More generally, the whole principal of saving for retirement is the basic recognition that if a household wants to equalize its spending over time, it must forgo some consumption in the early years (i.e., spend less than it makes and save the rest) in order to have dollars to cover spending needs in the later years (when there’s no longer any income from employment). Some researchers have even tried to develop “National Savings Rate” guidelines to help accumulators understand what percentage of income to save at various ages to replace their income in retirement.

This concept has been embodied in the economics research as the Life Cycle Hypothesis by Modigliani and Brumberg. And in fact, while households do face some difficulty to perfectly apply the theory – not the least because there’s uncertainty about how long they will live in the first place – the theory has generally been empirically validated over the years, and we find that at least many households really do seem to pursue an effort to maintain constant spending over time, saving excess income when possible during the working years and then spending it down later in retirement.

How Family Disrupts The Percentage-Of-Income Saving Approach

Notably, while it appears that households do try to save income during their working years to have assets available to fund retirement, it’s not necessarily done in practice by simply saving a steady percentage of income throughout.

Sometimes, the percentage-of-income approach fails because of “lifestyle creep” as one’s standard of living lifts up over time (which distorts the required savings percentages over time). In other cases, getting a big raise can lead to a permanent change in lifestyle spending, which means accumulators may need to save a percentage of their raises (not just a percentage of their income) to keep up.

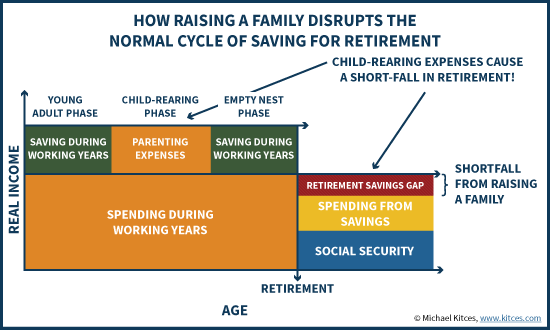

But for many retirement accumulators, the biggest disruption to saving a percentage of income is the remarkably common decision to start a family and have children.

From the perspective of saving, the addition of children to the family picture raises immediate questions, such as “is it better to save first for college, or retirement?” Although for most families, the biggest issue is not where to send the savings, but the mere fact that it’s suddenly much harder to save once kids are brought into the picture! In fact, in a world where a young adult might only be saving 10% or 20% of income, and it costs an average of almost $250,000 just to raise a child, for many families the introduction of children means savings goes straight to zero when the kids arrive!

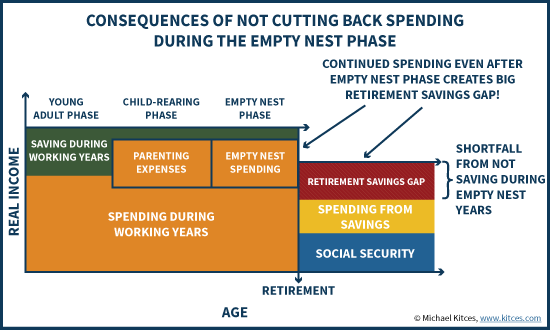

In other words, the cost of kids can crowd out retirement savings altogether for an extended period of years. And an extended period of time during the child-rearing phase where no saving is happening (or the saving is going towards future college expenses rather than retirement) means that by the time retirement arrives, there's now a retirement savings gap - a shortfall that was created by the years when saving for retirement just wasn't feasible.

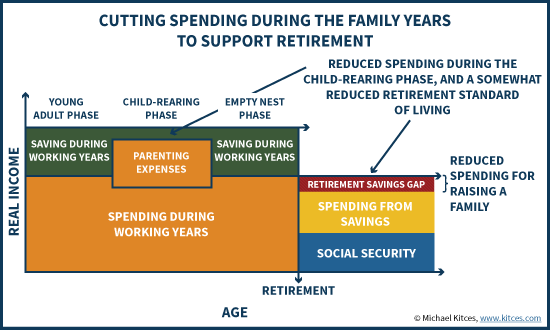

Accordingly, for those who ultimately do want to retire and maintain their lifestyle, the consequence of a decision to add children to the picture is that it forces a reduction in other spending, too. In other words, the household has to go through an extra round of belt-tightening, just as the kids arrive, to be able to still save during the child-rearing phase, and at least reduce the size of the shortfall attributable to raising a family. Even then, the retirement standard of living may end out being a bit lower than what it would have been before.

Notably, though, even for families that are able to reduce spending during the working and family years, the “save a percentage of income” approach is still out the window. The savings window is still much smaller during the child-rearing phase than it was when they were still young adults (before having kids), and what can potentially be saved again after raising kids (during the “empty nest” phase before retirement).

Using The Empty Nest Phase For Retirement Catch-Up

Given these dynamics, it is perhaps no surprise that one study after another continues to show that those in their 50s approaching retirement are quite far behind on their retirement savings goals and lack confidence in their own preparedness for retirement. Because for many in this phase, they have just recently come out of the child-rearing phase, and not surprisingly have little retirement savings to show for it.

Yet indirectly, this also makes the point of why the “save a percentage of income” approach is ineffective. Because those in the empty nest phase have a unique opportunity to save a particularly large percentage of their income and play “catch up” as the family expenses wind down! In other words, saving a percentage of income as a young adult becomes unrealistic in your 30s and 40s as kids crowd out the ability to save much at all, and then understates the saving need (and opportunity) in your 50s and early 60s once the kids are out of the house!

In turn, what this suggests is that the transition into the empty nest phase is actually the key moment for retirement savings. For those who continue their family spending at the same pace - substituting what were previously parenting expenses with other spending as more free cash flow becomes available - the retirement savings gap will remain as large as it ever was. Or even worse, higher lifestyle spending during the empty nest phase just makes the couple face even more of a retirement shortfall, as the already-meager retirement savings definitely cannot support the higher empty-nest-phase spending pace.

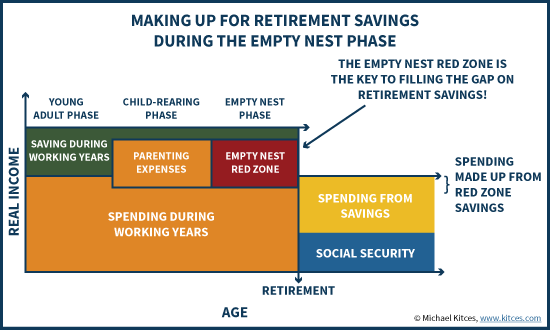

On the other hand, for those who allow their total family consumption to fall (now that Mom and Dad are only supporting Mom and Dad, and not the kids), a significant uptick in savings can almost entirely make up the lack of savings during the child-rearing phase. In other words, if all the money that used to be spent to raise a family and send kids to college is now redirected into saving for retirement, a couple might find themselves suddenly leap from saving less than 5% of income to being able to save 25% or more!

In essence, then, what happens to the spending that "used to be spent" on the children creates a form of "empty nest red zone" - a key chunk of spending for a period of years that can dominate the outcome of whether the couple successfully reaches retirement later, or finds themselves facing a worse shortfall than ever.

In fact, the assumptions made about this “empty nest red zone” – what happens to the extra expenses associated with kids during the child-raising years that becomes “available” in the empty nest phase – is a key factor in determining whether most households are really behind on retirement or not.

For instance, the Center for Retirement Research notes that the National Retirement Risk Index (NRRI) finds a whopping 52% of households may be at risk for a retirement shortfall. However, a study by Scholz, Seshardi, and Khitatrakun in the Journal of Political Economy found that the number of households facing a shortfall is less than 20%, and the deficit for those who are undersaving is relatively small.

And how do we account for the dramatic difference in outcomes between the two studies, and whether today's 50-somethings are really behind on their retirement savings or not? The primary difference between the two: how they account for the empty nest red zone. While the NRRI analysis assumes level spending throughout the working years and retirement, the Scholz et al. study assumes that empty nesters save more once they are able to (and also that retirees spend less in the later years of retirement), and these considerations actually eliminate a huge portion of the retirement readiness gap altogether!

Implications Of Uneven Household Spending During The Child-Rearing Years

Ultimately, the implications of considering how household spending is likely to be “uneven” during the child-rearing family phase is significant.

First and foremost, it implies that doing limited or even zero saving during the child-rearing phase – or conceivably even “negative” saving and accumulating some debt – is actually normal, and expected, and absolutely fine... as long as the couple is prepared to maintain their personal spending after the kids leave the house and use the empty nest phase as an opportunity to finish their retirement saving. In other words, making parents in their 30s and 40s feel guilty for not saving enough is unnecessary (and in some cases even cruel to suggest).

Second, it suggests that the crucial moment to focus on is specifically how parents adapt their spending as they transition into the empty nest phase. At this juncture, “just” returning to their pre-family habits of saving a moderate percentage of income may be wholly insufficient, but saving a larger percentage may actually be quite feasible and realistic. However, the prospective retirees need to be warned and prepared in advance that the empty nest phase is not a license for spending their newfound discretionary dollars, but instead simply a normal opportunity to make up for prior years when saving just wasn’t feasible!

On the other hand, it’s worth noting that as the median age for starting a family continues to rise, the entire process of when kids cause savings to be reduced, and in turn the onset of the empty nest phase when savings can rise again, has been shifted later in the lifecycle; in other words, we get to the child-rearing phase later, and then we come out of it much older (and potentially much closer to retirement). To the extent that the full retirement age for Social Security has also shifted later, though, and medical advances have given us more productive working years, this may not necessarily be a problem. Although indirectly, it does emphasize the importance of a social safety net for those who unfortunately find themselves unable to work in their 50s and 60s, just as the empty nest phase – and higher retirement savings – were otherwise “supposed” to kick in.

Nonetheless, the fundamental point remains that the feared “retirement shortfall” for those in their 50s and early 60s may actually be significantly overstated, and that the key conversation to have is not about the doom and gloom of having too little in retirement savings already, and simply the opportunity that exists to quickly make up the shortfall during the empty nest phase. After all, the reality is that even with a “normal” savings trajectory, a retiree who wanted $1,000,000 at retirement would have less than half that amount with a decade to go. Someone who had the ability to save aggressively – thanks to available discretionary income during the empty nest phase – can bridge the gap even faster.

For instance, a couple earning $100,000 that reaches the empty nest phase (and their peak earnings years!) in their early 50s and still has 15 years left for retirement can accumulate over $1,000,000 of retirement savings by “just” saving 30% of their income and investing for growth (an 8% growth rate). While there’s some retirement date risk that market returns may not align perfectly, that’s still a remarkable “catch-up” in retirement savings for someone who might have hit the empty nest phase with $0 in their retirement accounts! And if they had anything more than $0 of retirement savings as they transitioned to the empty nest phase, the outcome would just be even better!

The bottom line, though, is simply this: perhaps it’s time to stop guilting parents in their 30s and 40s about not saving enough, and recognize the savings opportunity for empty nesters in their 50s and 60s. Because telling parents to save 10%-20% of their income during the child-rearing phase may be unrealistic, and telling empty nesters to save 10%-20% of their income may underestimate their ability to save and get their retirement on track!

So what do you think? Do we put too much pressure on parents to save during the child-rearing years? Is it better to recognize that realistically, most parents will do most of their savings during the empty nest phase? Please share your thoughts in the comments section below!