Executive Summary

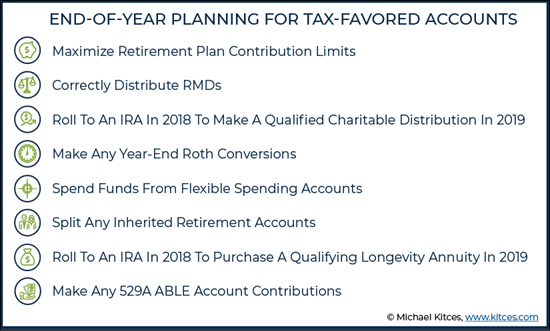

Of the many ways that financial advisors try to provide demonstrable value-added services for their clients, one of the most effective is making the most efficient use possible of tax-advantaged savings accounts, for the hard-dollar tax savings it can create. And while it often takes consistent planning through the year to make the most of those accounts, the end of the year provides the opportunity to make a number of last-minute changes, not only in order optimize contributions and distributions, but potentially to avoid any unnecessary and preventable costs as well.

For those with the means to do so, the first, most obvious first step is to make sure that they’ve contributed as much as they can to any available qualified retirement plans through their employer(s), and even consider establishing (or changing) a separate employer retirement plan for any side businesses that the individual may own in order to take advantage of the (non-coordinated) employer limits for defined contribution plans, which in 2018, stands at up to $55,000 per non-related business (plus catch-up contributions!).

Meanwhile, those 70 1/2 or over have the opportunity to manage their tax exposure by making (up to) $100,000 in Qualified Charitable Contributions (QCDs) from pre-tax funds in their IRA, which counts towards their Required Minimum Distribution obligations as well (thus allowing them to minimize both their taxable income and their Adjusted Gross Income). Especially since QCDs have become even more valuable following the passage of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act… as with the steep increase in the standard deduction, most taxpayers won’t itemize deductions in the future, and therefore taking RMDs and then donating to charities won’t provide any offsetting deduction on their tax return in the future (but donating from an IRA via a QCD is still a perfect pre-tax donation!).

Continuing in that same post-Tax-Cuts-and-Jobs-Act-landscape vein, year-end Roth conversions are now even more valuable from a planning perspective. Because, even though the overwhelming majority of taxpayers will have lower tax bills in 2018 than in 2017, the most impactful cuts for individuals are scheduled to expire in 2025, which means that they have a relatively limited window in which they can make Roth conversions at a lower rate than would otherwise be possible in the future. Yet going forward, taxpayers may increasingly need to wait until the end of the year to decide exactly how much to convert, as TCJA also eliminated Roth recharacterizations (making the Roth conversion itself a one-time irrevocable decision).

And, although much of the focus at the end of the year is on optimizing savings, advisors should also pay attention to any tax-favored funds individuals may have in a healthcare flexible savings account (FSA) that should be spent before the end of the year, given their inherent “use-it-or-lose-it” provision. And while some employers may give employees the option to carry over up to $500 on a year-to-year basis, or utilize a 2 1/2 month grace period the following year, the fact is that money inside an FSA needs to be spent… preferably in a way that doesn’t involve negative outcomes for the individual’s well-being.

Other planning options advisors have at their disposal for end-of-year tax planning include rolling over employer retirement plans to an IRA in anticipation of purchasing Qualified Longevity Annuity Contracts in 2019, and (when appropriate) utilizing Achieving a Better Life Experience (“ABLE” or 529A) accounts, which are accounts that allow for tax-deferred growth and distribution of funds used for ongoing disability expenses for those who were disabled prior to age 26.

But, ultimately, the key point is to recognize that year-end planning around tax-advantaged accounts is just another way that advisors can provide great service for their clients… with real tangible hard-dollar savings. And while some of these planning issues may be relatively straightforward, the fact is that optimizing the use of tax-advantaged accounts often requires a nuanced look and properly navigating what are sometimes complex rules and provisions.

When it comes to year-end planning, there are few areas where advisors can add more value than with respect ensuring the effective use of tax-favored accounts, given both their tax-preferenced nature itself, and the fact that many of their deadlines are tied directly to the end of the calendar year. That includes “obvious” objectives such as making sure that workers are contributing the correct amounts (often as much as possible up to the statutory limits), and to the right tax-favored accounts. But year-end planning for tax-favored accounts also includes less top-of-mind issues, such as managing key deadlines for using the money, moving the money, and/or avoiding other costly mistakes.

While making the most of tax-favored accounts is often best accomplished with year-round planning, there is generally a heightened importance and urgency as the end of the year approaches. And with that in mind, here are some important year-end planning strategies to consider with respect to planning for/around tax-favored accounts.

Maximizing Retirement Plan Contribution Limits

The first step that an advisor should take prior to the end of the year is ensuring that savers with the free cash flow to “max-out” their available retirement plan(s) do so. For 2018, the 402(g) limit on salary deferrals to 401(k)s and similar plans is an $18,500, with an additional catch-up contribution of $6,000 available to those 50 or older by the end of the year. Though unlike IRA contributions, which can be made for 2018 up through April 15 of 2019, salary deferrals for 2018 must generally be completed by the end of the year (i.e., by December 31st of 2018).

Meanwhile, the 415(c) overall limit on annual additions to defined contribution plans maintained by the same employer is $55,000 for 2018. This non-coordinated limit can be especially meaningful for those who, in addition to working their primary job, also have a “side-gig.” In such situations, advisors should not only consider whether an individual has maximized contributions to their existing retirement plans, but they should also consider whether starting a new (or different) plan for the individual’s own (separate) business could allow them to save even more on a tax-favored basis.

To compare the savings opportunities available to sole-proprietors and other small businesses quickly, advisors can do the math themselves or use any number of online calculators (e.g., this one from Vanguard, which calculates the maximum contribution available between different defined contribution plan types, though it will not help determine whether contributions will need to be made, and in what amounts, for other employees, if applicable.) In the event that a plan with a year-end establishment deadline, such as a 401(k), will afford an individual with the greatest ability to maximize savings potential, action to establish such a plan should be taken promptly.

In addition to any employer-sponsored retirement plans to which a saver may have access, including their “own plan,” individuals with the available cash flow can also consider contributing to an IRA or Roth IRA for 2018. Since the deadline for such contributions is not until April 15, 2019, however, they are not generally a critical year-end task.

Correctly Distributing RMDs Prior To Year-End

No year-end planning for retirement accounts would be complete without checking to make sure RMDs have been correctly distributed. Other than the year in which the individual reaches the age of 70 ½ - when the RMD for the year can be taken as late as April 1st of the following year – RMDs for each year must be taken within that calendar year. Thus, most RMDs for 2018 must be taken by December 31, 2018.

When reviewing accounts to make sure that they have appropriately distributed their RMDs for the year, advisors should pay special attention not only to ensuring that the proper total amounts have been taken, but also that those amounts have been distributed from the appropriate accounts. While RMDs for multiple IRAs can be aggregated and taken from any IRA or combination of IRAs, with the exception of 403(b) accounts (which follow a similar rule to IRAs), each of an individual’s employer retirement plan RMDs must be calculated and taken separately for/from each plan.

For those who still have IRA RMDs amount left to take, and who are charitably inclined, the Qualified Charitable Distribution (QCD) should be given strong consideration. Such distributions can be used to “offset” up to $100,000 of an IRA owner’s cumulative IRA RMD each year, and is generally a far more tax-efficient way of giving to charity than taking a “normal” RMD and writing charity a check (and hoping) to get an itemized deduction.

Unfortunately, though, for those IRA owners who have already taken their IRA RMDs for the year, there is no way to retroactively treat those distributions as a Qualified Charitable Distribution (and by definition, for anyone over age 70 ½, any distribution taken earlier in the year is automatically deemed to have been allocable to any RMD obligations first). In addition, those individuals who have RMDs from accounts other than IRAs (e.g., employer retirement plans) are not eligible to use the QCD for those RMDs in the first place and instead can only plan now to be able to utilize the QCD next year.

Rolling To An IRA In 2018 To Make A Qualified Charitable Distribution In 2019

The rules for IRAs, 401(k)s, 403(b)s, and other retirement accounts are extraordinarily similar to one another. That said, there are some meaningful differences between the rules for different types of accounts from time to time. An important case in point example… the QCD.

Because for retired persons who are 70 ½ or older and charitably inclined, one of the most critical differences between keeping money in an employer-sponsored retirement plan versus rolling those funds over to an IRA, is that QCDs can only be made using the pre-tax funds inside of an IRA (including inactive SEP and SIMPLE IRAs, as well as inherited IRAs). They cannot, on the other hand, be made from 401(k)s, 403(b)s, or similar account.

QCDs allow IRA (and inherited IRA) owners who are 70 ½ or older to donate up to $100,000 annually directly from their IRA to qualifying (public) charities. The amount of the QCD counts towards satisfying the IRA owner’s required minimum distribution, and while the IRA owner does not receive a tax deduction for the transfer to charity, that’s only because it’s naturally a pre-tax contribution since it comes from a pre-tax account and the distribution will never be added to their income to begin with!

This trade-off is virtually always superior to the “strategy” of taking an RMD and separately donating cash in the same year to charity, because it not only helps to minimize an IRA owner’s taxable income (on which their tax bill is calculated), but it also helps to minimize Adjusted Gross Income (or AGI, to which most of the undesirable income-related phaseouts are tied).

And in the post-Tax-Cuts-and-Jobs-Act world, the QCD is even more valuable, given that with the increased standard deduction – an increasingly tough hill to climb, especially when you consider the $10,000 cap on state and local tax deductions, and the fact that many retired individuals have already paid off their mortgage (or at least are deep enough into their mortgage that the overwhelming majority of the payments represent payments of principal, and not tax-deductible interest) – only about a third of those previously itemizing deductions will still be using that method going forward. Which is important because those who can no longer clear the standard deduction ($24,000 in 2018, increased to $26,600 for couples over age 65, and rising to $27,000 in 2019), the net tax benefit of a charitable contribution is $0! Consequently, those who donate cash to a charity separately from taking their RMD will report income for the RMD but not an offsetting deduction for the charitable contribution, while non-itemizers who complete the transaction as a QCD instead retain the full pre-tax benefit of the charitable contribution!

So clearly, the QCD is the way to go for many charitably inclined IRA owners of RMD age. The “problem” on the other hand, is that some of these have most or all of their qualified funds in 401(k)s and similar accounts, which cannot be the source of a QCD. Obviously, though, there’s an easy fix here: roll those employer retirement plan funds over to an IRA first!

Notably though, in order to make use of the QCD in 2019 and have it satisfy all or a portion of the retiree’s RMD, the rollover must take place by the end of 2018. If not, there will be an end-of-2018 balance in the 401(k) (or similar plan), which triggers for 2019 an RMD that cannot be rolled over to the IRA and taken from there as a QCD because RMDs cannot be rolled over at all!

Example: Dennis is a 75-year-old single and charitably inclined 401(k) owner. The 401(k) is his only retirement account. He would like to give $5,000 to his favorite charity in 2019, which coincidentally, exactly equals his RMD for the year. Currently, Dennis has only $4,000 in other itemized deductions.

If Dennis leaves his 401(k) funds in his 401(k) through the end of the year, he’ll have a 2019 RMD for his 401(k) that must be taken from his 401(k) in 2019 (increasing his AGI). Further, since that RMD cannot be rolled over to an IRA (it must be taken from that 401(k)) and since a QCD may only be made from an IRA, Dennis will not be able to avoid the taxation of his RMD by donating it as a QCD. Of course, Dennis can still simply make his $5,000 charitable donation in 2019, but adding that donation to his existing $4,000 of itemized deductions brings his new total to only $9,000, which will not exceed his standard deduction threshold as an individual. Which means Dennis bears all the tax consequences of his 401(k) RMD, and gains none of the tax benefits of his charitable contribution!

Alternatively, if Dennis completes a rollover of his 401(k) to an IRA by the end of 2018, then his RMD for 2019 will be due from his IRA and not from his 401(k). Which in turn means he will be able to make a QCD in 2019 from his IRA. And that QCD will be able to both satisfy his RMD requirement and keep his AGI and taxable income exactly the same as if he’d not taken any IRA distribution at all (by virtue of the QCD rules allowing Dennis to exclude his RMD from income).

Year-End Roth Conversions

Year-end Roth conversions have long been a tool in the tax and retirement planner’s toolbox. But thanks to the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, the “year-end” Roth conversion, in particular, is arguably more relevant than ever.

Impact Of The TCJA Repeal Of Recharacterizations For Roth IRA Conversions

As a result of the TCJA’s repeal of recharacterizations for Roth IRA conversions, the emphasis on getting the conversion amount “right” beforehand (as opposed to the old strategy of doing so after-the-fact via a full or partial recharacterization) is critical. As a result, many planners have held off on making conversions for certain retirement savers until later in the year, when their income and deductions can more accurately be projected, to be able to determine exactly how much should be converted to fill the desired tax brackets (but not go any higher). Those year-end-projection-driven Roth conversions now need to be made before the end of 2018.

Impact Of TCJA’s Rate Changes On Roth IRA Conversions

In addition, there’s reason to believe that more people than ever should consider making Roth conversions in 2018 than ever before. Thanks to the TCJA’s many changes, the overwhelming majority of taxpayers will have lower tax bills for 2018 than they did for 2017. Even many taxpayers in high-tax (and heavily-SALT-cap-impacted) states will see lower tax bills (given that many of them weren’t actually able to fully deduct their SALT payments anyway in the past, due to their exposure to the Alternative Minimum Tax!).

The issue, however, is that these lower tax bills are primarily the result of temporary changes made by the TCJA. And while the changes to the corporate tax code were largely permanent, the majority of big changes impacting the annual tax bills of individuals are set to expire at the end of 2025… including the lower income tax brackets, the increased standard deduction, the enhanced child tax credit, and of course, the critical QBI (Qualified Business Income) 20% deduction.

While it’s certainly possible for these tax “breaks” to be extended beyond the 2025 sunset (just as President Bush’s “temporary” tax cuts from 2001 to 2003 were eventually extended beyond their 2010 sunset and ultimately made permanent after 2012), that will require action by Congress… and absent any action, the majority of these individual tax breaks will sunset on their own. And with a split Congress supporting deeply divided bases, compromise of any kind may be tough to come by for a long time.

And if the cumulative effect of the TCJA’s changes for most taxpayers is that they currently enjoy lower tax rates than they did prior to the law’s changes, it stands to reason that when those changes expire, their tax rates will rise again! Thus, there may be a limited 8-year window in which savers can make Roth IRA conversions at lower-than-otherwise-projected rates (or maybe the rates will be extended further… or maybe a new Congress will try to reduce the debt and/or balance the budget by increasing rates higher than they were even before the TCJA was passed… or perhaps Congress will reduce individual income tax rates even further and lift Social Security and Medicare taxes or a new VAT tax instead).

Of course, the to-Roth-or-not decision is driven by more than what happens with the tax brackets themselves. It’s ultimately driven by the individual’s marginal tax rate now, versus what it is projected to be in the future, which requires consideration of more than just the statutory tax bracket rates, and also the impact of deductions and credits and any income-related phaseouts. Thus, even in light of TCJA changes making Roth conversions more attractive now on the whole, it’s important not to forget about the “regular” Roth conversion questions that impact the final decision, such as “How will your income change going forward?”, “Will there be changes in your deductions and/or credits?”, and “Is your filing status likely to remain the same?"

Year-End Spend-Planning For Flexible Spending Accounts

Unlike retirement accounts, where most of the focus is on contributing and accumulation, year-end planning for healthcare flexible spending accounts (FSAs) often revolves around spending the money in the account. That’s because unlike other tax-preferred accounts, healthcare FSAs come with a use-it-or-lose-it provision (or, at best, a use-most-of-it-or-lose-it provision).

When it comes to healthcare FSAs, the general rule is that any money left in a participant’s account at the end of the year is forfeited to the employer. (Note: employers have several options for forfeited funds, including simply retaining the funds, using them to offset the plan’s administrative costs, and returning them to employees on a reasonable and uniform basis. However, due to the administrative burdens of returning money to employees, including potentially having to “track down” former employees, that option is rarely used.) Indeed, for many years, this was the rule for healthcare FSAs, period.

Optional Healthcare FSA Grace Period Or Carryover Provisions

However, in 2005, the IRS released Notice 2005-42, which allowed employers to add a two-and-one-half-month grace period into the following year, during which time healthcare FSA participants can spend the prior year's “leftover” funds before they are lost. Then, in 2013, the IRS added a second option for employers via IRS Notice 2013-71, which allows employers a provision which allows healthcare FSA participants to carry over up to $500 of healthcare FSA funds to the following year without being subject to forfeiture.

Notably, both the two-and-one-half-month grace period and the $500 carryover provisions are optional on the part of the employer. Furthermore, they cannot be used in conjunction with one another. Thus, some healthcare FSA participants must still spend all of their plan funds prior to year-end to avoid losing them, while other participants must spend down plan funds to the $500 mark to avoid losing the excess. Those participants whose plans utilize the two-and-one-half-month grace period get a temporary reprieve but may find themselves in a similar position early next year if they still have not spent through their 2018 contributions.

Making The Most Of Otherwise Forfeitable Healthcare FSA Funds At Year-End

Clearly, there’s no reason not to spend excess (otherwise forfeitable) healthcare FSA funds. But you can’t exactly make yourself sick or injured… or at least you wouldn’t want to, right?

In such cases, where healthcare FSA participants have had the good fortune of not visiting the doctor or requiring medications or other healthcare-FSA-eligible medical interventions as much as anticipated, advisors should help individuals identify medically-related expenditures that, even if not currently needed, can be purchased with healthcare FSA funds now, and (likely) used later. Commonly used qualifying expenses with at least moderate “shelf lives” that can be purchased (without a prescription) include athletic braces and supports, sunscreen, contact lens solutions, first aid supplies, thermometers, reading glasses, and even condoms. In addition, many over-the-counter medications, some of which have reasonable shelf lives, may be purchased with healthcare FSA funds with a prescription. (A more complete list of eligible medical expenses is available in IRS Publication 502, Medical and Dental Expenses.)

Once you’ve fixed the 2018 “problem” of too much healthcare FSA money, it’s also worth turning some attention to 2019. Changes to FSA contribution amounts can be made during an existing participant's open enrollment – which many employers are holding now towards the end of the current calendar year – or upon certain triggering events, such as a birth or a change in marital status. Participants with consistent year-end excess healthcare FSA funds should consider scaling back on contributions for 2019. Conversely, those who did not “max out” 2018 healthcare FSA contributions and ran out of plan funds with which to pay qualifying medical expenses should consider increasing contributions for 2019, up to a maximum of $2,700 (up from $2,650 for 2018). Such contributions not only reduce a participant’s income tax but also reduce FICA and FUTA taxes as well.

Similar rules and planning apply to dependent care FSAs, to which forfeiture rules also apply. However, while employers can adopt a two-and-one-half-month grace period for dependent care FSA, similar to that of healthcare FSAs, there is no option to adopt a $500 carryover provision. So even in a best-case scenario, participants have until the middle of March to spend all 2018 contributions, before remaining amounts are forfeited. Nevertheless, since childcare is often more expensive than the $5,000 statutory limit on dependent care FSA contributions (applicable to both 2018 and 2019), and since childcare expenses are more predictable than medical expenses, the dependent care FSA use-it-or-lose-it rule is rarely as problematic as its healthcare FSA counterpart.

December 31 Separate Account Deadline For 2017 Inherited Retirement Account Beneficiaries

Another critical year-end task, for those who inherited IRAs, 401(k)s, and similar accounts last year (in 2017) is to be certain to split the account by December 31st of 2018 in order to obtain “separate account” treatment (presuming they were not the only beneficiary in the first place). As in general, multiple beneficiaries of a single retirement account are “stuck” using the age of the oldest beneficiary to calculate RMDs… unless the inherited accounts are timely split by December 31st of the year following the year of the original owner’s death, and then each beneficiary is able to utilize their own age to calculate their inherited IRA RMDs (stretch distributions).

In situations where there are multiple beneficiaries of a retirement account who are relatively close in age, ensuring 2017 inherited accounts are split by the December 31, 2018 deadline will be of some benefit, but will likely not have a dramatic impact on the beneficiaries (as their life expectancies for stretch IRA purposes aren’t substantially different anyway). On the other hand, in situations where one beneficiary is significantly older (or younger) than other beneficiaries, making sure that the inherited IRA is timely split can offer the younger beneficiaries substantial tax benefits.

Common situations to be on the lookout for where timely account splitting for separate account treatment is particularly valuable include when a retirement account owner’s spouse and children are each named as partial beneficiaries of the same account, and when a charity is named as a partial beneficiary of a retirement account along with other would-be designated beneficiaries.

December 31 Deadline For Employer-Sponsored Plan Beneficiaries To Roll Over To An IRA To Preserve The Stretch

December 31, 2018 is a critical deadline for another group of 2017 beneficiaries: non-spouse designated (i.e., individual) beneficiaries of employer-sponsored retirement plans that do not offer the ability for beneficiaries to stretch directly from the plan.

As under IRC Section 401(a)(9), employer-sponsored defined contribution plans like 401(k)s can offer beneficiaries the option of stretching distributions, in the same manner that is typically available to IRA beneficiaries. But while plans can offer such a favorable distribution schedule to beneficiaries, under Treasury Regulation 1.401(a)(9)-3, Q&A-4, plans are not required to do so and in fact, can choose not to make the option available. As even well-intentioned employer retirement plans don’t necessarily want to deal with distributions to a 1-year-old child beneficiary for the next 80 years just because an employee worked at the company for 1 year and made a small contribution that the beneficiary chooses to stretch!

Accordingly, many employer-sponsored retirement plans require distribution of inherited plan funds much faster, and often in as little as five years. Clearly, this is far less beneficial than stretch distributions, especially for younger beneficiaries.

However, while the general rule is that if a plan forces distributions at an accelerated rate plan beneficiaries must comply with those rules, there is an exception to this general rule for non-spouse individual beneficiaries of employer retirement plans who directly rollover their inherited plan funds to an inherited IRA by December 31st of the year following the year of the plan owner’s death.

After making such a timely direct rollover, a designated beneficiary can use the IRA custodian’s post-death RMD distribution options (almost always the stretch, by default) to calculate their RMD, as opposed to the employer retirement plan’s accelerated distribution schedule. If a designated beneficiary missed the December-31-of-the-year-after-death deadline, they may still complete a direct rollover of plan funds to an inherited IRA, but they would have to distribute funds from that inherited IRA in accordance with the employer retirement plan’s original distribution schedule (which continues to be the 5-year rule if that’s what the plan originally stipulated).

Rolling To An IRA In 2018 To Purchase A Qualifying Longevity Annuity In 2019

There’s little question that the number one concern of most retirees is running out of money before they run out of life... and that planners spend a great deal of time trying to figure out the best way to try and avoid that retirement nightmare. While as the expression goes, there’s often “more than one way to skin a cat,” arguably one of the most useful – and also underutilized – tools to combat longevity risk is the longevity annuity.

Notably, recognizing this issue and potential solution, the IRS released final regulations in 2014 allowing certain types of longevity annuities – so-called “Qualifying” Longevity Annuity Contract (QLACs) – to be held inside of retirement accounts (without otherwise running afoul of the IRA owner’s RMD obligations).

While the regulations permit QLACs to be purchased with both IRA money as well as employer retirement plan funds, in order to use plan funds to make such an investment, the plan itself must offer a QLAC as an investment option. And to date, and for a variety of reasons, few plans have done so. Thus, while technically it’s possible for an individual to have the ability to purchase a QLAC within their 401(k) or similar plan, the reality is that in order to do so, they will probably have to use IRA funds.

A problem may arise, however, for those contemplating a 2019 purchase of a QLAC, but who have no IRA money as of the end of 2018. The issue stems from the formula determining the maximum QLAC purchase in a given year. For IRAs (there is a slightly different rule for employer retirement plans), a QLAC purchase is limited to the lesser of $130,000, or 25% of their combined IRA assets as of the prior-year-end.

Clearly, if there is no IRA balance as of the end of the prior year, then the lesser of those numbers is 25% of $0 which is… well… problematic if you want to purchase a QLAC in 2019! And while it is certainly possible to roll plan money over to an IRA mid-year in 2019, that won’t change the 2018 year-end balance and thus, no QLAC purchase will be feasible within the IRA until at least January 1, 2020. By that time, the individual will be a year older, and the QLAC’s long-term value (and ability to accumulate mortality credits) may be somewhat diminished relative to if it were purchased in 2019 when the retiree was a year younger.

Furthermore, since QLAC funds are able to be excluded from a retiree’s prior-year-end balance when calculating their RMD (but “regular” IRA money cannot), the no-IRA-money-as-of-December-31-2018-induced delay in purchasing the QLAC will make the 2020 RMD higher than it would have been had a QLAC been purchased in 2019. Thus, for individuals who may wish to consider a 2019 QLAC purchase, but who cannot do so within their employer retirement plan, and have no (or limited) IRA funds available, a pre-year-end rollover may make a ton of sense. Though bear in mind that because the IRA purchase limit is the lesser of $130,000 or 25% of the IRA account balance, those planning to allocate a certain dollar amount to a longevity annuity in 2019 must plan to roll over 4X that amount – up to a maximum of $520,000 – by the end of 2018 (to fit the 25%-of-assets limitation).

Year-End 529A ABLE Account Stuffing

In 2014, Congress passed the Achieving a Better Life Experience Act, creating new IRC Section 529A, which gave us the Achieving a Better Life Experience (ABLE) account, which allows for tax-deferred growth and ultimately tax-free distributions for beneficiaries who were disabled prior to the age of 26 to pay for their qualified disability expenses (as opposed to 529 college savings plans, which provide tax-free distributions for qualified education expenses).

In addition, as long as the account’s balance does not exceed $100,000, the funds in a 529A plan (and the distributions from it for the disabled beneficiary) will not impact the beneficiary’s eligibility for means-tested federal programs, including SSI benefits. Which makes them a potentially appealing alternative option to, or at least a supplement for, a special needs trust.

But there’s no way to create tax-free earnings in an ABLE account if such an account has not been funded! And 529A accounts do have an annual contribution limit (cumulatively, from all sources), of just $15,000/year in 2018 (the annual gift limit). Thus, prior to the end of the year, advisors should identify those who were either disabled, themselves, prior to 26, or who provide (or want to provide) material support for such an individual, such as a child or grandchild, as with very limited contribution limits, it’s important not to “miss” a year for disabled beneficiaries who may need to accumulate substantial balances to provide for their long-term future.

Notably, beginning in 2018, disabled individuals who are ABLE account beneficiaries and are gainfully employed can also make an additional contribution to their own ABLE account equal to the lesser of their compensation for the year, or the federal poverty line amount for a one-person household. For 2018, the federal poverty line amount for a one-person household is $12,140 for those in the continental U.S., $13,960 for those living in Hawaii, and $15,180 for those living in Alaska. In essence, this means that disabled beneficiaries who are working can effectively contribute their own income to their own (529A) savings account to receive future tax-free growth (ostensibly while relying on their existing aid and care systems to provide for their current needs).

Of critical importance as the end of the year approaches is that the ABLE account contribution deadline is December 31st of the year for which the contribution is being made. Thus, 2018 ABLE account contributions must be postmarked by December 31, 2018.

Tax-favored accounts offer a variety of substantial tax benefits for taxpayers. Those benefits, however, come at the “expense” of a significant amount of complicated and potentially burdensome rules. As the end of the year quickly approaches, advisors should ensure that these accounts are given the special care and attention they require, to ensure individuals are compliant with all relevant rules,and are effectively maximizing available opportunities.

Leave a Reply