Executive Summary

Building a business as a financial advisor (or really, almost any business) is a constant effort of getting “more” – more clients, more revenue, more staff to serve them… in a process that can often leave the advisor feeling less and less in control as the demands of the business become overwhelming.

In the new book “Essentialism”, Greg McKeown makes the case that this “Paradox of Success” – the focus that makes entrepreneurs succeed becomes their undoing as the demands on their time increase due to the very success they created – can only be resolved by taking a systematic approach to creating focus on what is truly essential for the advisor to be doing. The classic approach of doing more and more – of multitasking and multifocusing – just leads to less and less productivity. Which means it’s actually the disciplined pursuit of less – what McKeown calls living the life of an “Essentialist” – that leads to more in the long run.

And ultimately, the lessons of Essentialism translate not only into personal success, but the entire design and focus of a business, where in a similar manner a strategic “focus” that goes in too many directions at once leads to little progress at all. By contrast, it’s the focused “Essentialist” business that puts all of its energy towards a single niche or specialization that can make the most progress and gain the momentum that sets the stage for future success as well.

What Is Essentialism?

In his book “Essentialism: The Disciplined Pursuit of Less”, author Greg McKeown makes the case for why the key to success as a busy professional is not about figuring out how to improve your productivity and efficiency so you can do more, but instead in figuring out how to do less. Because it’s only by doing less that we can make a concerted effort to focus on the most “essential” things that we personally must do, and avoid being distracted by the rest. Or as Chinese author Lin Yutang once said, “The wisdom of life consists in the elimination of non-essentials.”

In his book “Essentialism: The Disciplined Pursuit of Less”, author Greg McKeown makes the case for why the key to success as a busy professional is not about figuring out how to improve your productivity and efficiency so you can do more, but instead in figuring out how to do less. Because it’s only by doing less that we can make a concerted effort to focus on the most “essential” things that we personally must do, and avoid being distracted by the rest. Or as Chinese author Lin Yutang once said, “The wisdom of life consists in the elimination of non-essentials.”

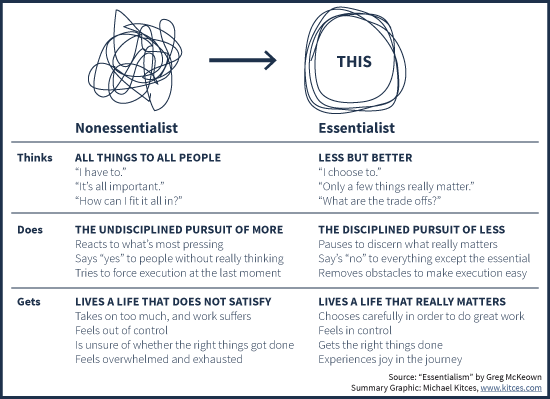

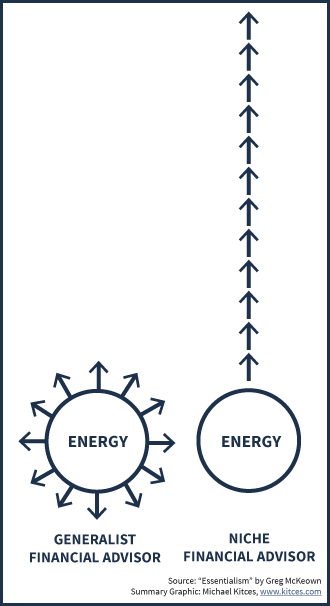

The core concept of this “Essentialism” approach is that most of us exert energy in lots of different directions simultaneously, which limits our ability to make progress on any one thing in particular. In other words, just as a growing base of research is showing that multitasking doesn’t actually let us be more productive and get more done and instead just distracts us and takes a mental toll, McKeown suggests that “multi-focusing” is even worse in limiting our ability to make progress towards our goals. “Focusing” in multiple directions at once expends a lot of energy with limited progress; stacking up all that energy in a single direction propels us forward.

Accordingly, the whole point of being “an Essentialist” is to think about what few things you can do (in your business, in your life) that really matter and have impact, and purposefully choose to pursue those things (and only those things), rather than our typical default of trying to be all things to all people. And of course, since the reality is that saying “no” to people and opportunities is difficult, it takes discipline – which is why McKeown suggests that Essentialism is about the disciplined pursuit of less… as contrasted to the approach that most people take, the ‘undisciplined pursuit of more’ where we’re constantly reacting and saying yes to opportunities that present themselves (without always thinking about whether it’s really constructive in the long run, because it’s easier to say “yes” than tell someone “no”).

The goal in the end? To direct your focus in a manner that has impact, allowing you to do your best work, feel in control, and “live a life that really matters”… hopefully even enjoying the journey along the way.

Having A Niche Focus And Essentialism In The Business Of Financial Planning

In the context of being a financial advisor, the dichotomy of the Essentialist and the Non-Essentialist bears a striking resemblance to being a niche-focused advisor versus the (more typical) broad-based generalist.

Like the Non-Essentialist, the generalist financial advisor tries to be all things to all people, to fit in every possible potential client they might meet. Yet the challenge is that, as noted earlier, the undisciplined pursuit of more clients leaves the advisor with scattered energy, and builds no momentum in any direction. The advisor ends out stuck in a reactive mode to whatever recent client issue is most pressing, and struggling to execute. When there’s no focus to the advisor’s target clientele, the “good” news is that every situation presents a new and interesting challenge (at least, that’s good if you like problem-solving!); the bad news is that as a result, no efficiencies emerge in serving clients, because every question is different and new. So getting more clients just means a larger number of people who all have different questions and different demands, and force the advisor to be increasingly reactive.

Like the Non-Essentialist, the generalist financial advisor tries to be all things to all people, to fit in every possible potential client they might meet. Yet the challenge is that, as noted earlier, the undisciplined pursuit of more clients leaves the advisor with scattered energy, and builds no momentum in any direction. The advisor ends out stuck in a reactive mode to whatever recent client issue is most pressing, and struggling to execute. When there’s no focus to the advisor’s target clientele, the “good” news is that every situation presents a new and interesting challenge (at least, that’s good if you like problem-solving!); the bad news is that as a result, no efficiencies emerge in serving clients, because every question is different and new. So getting more clients just means a larger number of people who all have different questions and different demands, and force the advisor to be increasingly reactive.

Ironically, for so many of us as financial advisors, we’ve been trained so long that “this is the way things are done” we don’t even recognize how limited and reactive it has made us. Yet McKeown’s summary of what the Non-Essentialist gets – taking on too much work, feeling overwhelmed and exhausted, and feeling out of control – has stunning parallels to the recent FPA study on Time Management and Productivity of Advisors, where 74% of advisors work more than 40 hours/week (over 1/3rd work more than 50 hours/week!) and a mere 13% of advisors stated that they feel in control of their time and their business. Yet the reality is that this scattered-energy generalist path is a remarkably different than the focused momentum and efficiencies that build with the concentrated efforts of a niche financial advisor.

Generalist Vs Niche Financial Advisors

So how does an Essentialist approach and a niche-oriented practice resolve the issues that the generalist faces? To better understand, we can compare and contrast between a generalist and niche advisor over time.

So imagine for a moment two new advisors; the first, Jenny, aims to find her niche as a specialist working with the senior managers and executives at one large corporation (ABC Corp) in the area; the second, Barry, is a generalist advisor who sets up an office in the center of town, and simply aims to work with anyone that he can to get some revenue in the door.

When Barry tries to market his practice, it’s a scattershot approach, as ‘anyone’ Barry reaches could potentially be a client, so he just wants to reach as many people as possible. Accordingly, Barry has joined four networking groups in town, trying to build relationships with as many people he can, seeking out who will provide some referrals. He tries to meet with a few local attorneys and accountants to see if any of them will provide him some referrals, too, emphasizing that he can work with anyone they’re willing to send to him. He writes a handful of personal finance articles for the local paper to get his name out. He leases an office in a prominent location in the center of town and hangs a shingle that advertises the name of his firm. He occasionally does seminars, sending out a broad-based mailer to the city’s most affluent zip code, and hopes to get a “good” 2% response rate.

When Jenny aims to market her practice, she knows exactly where to go – anyone and everything associated with ABC Corp! Jenny might try establishing a relationship with ABC Corp’s HR department to schedule internal educational seminars at the company. She offers to write educational content for the company’s internal newsletter. She identifies the prominent executives, and tries to network her way into groups and local non-profit boards where she can connect with them. As she gets the first one or two executives as clients, she asks for referrals to the others, marketing herself as an expert in the company’s executive benefit programs (which she learns about as she does work with those executives!). She learns about the company’s broader employee benefits programs as well, and writes a detailed “how-to” guide for employees on making the best benefits elections, and the nuances to watch out for based on a few of the company’s unique rules; the employees can find these guides as they Google around to find answers to their questions. Jenny then builds a mailing list of the company’s employees who find their way to her expert content on her own website, signing up new subscribers to her drip marketing campaign as they share her guides with each other. She can even use social media to target further outreach to employees at the company.

Projected forward three years later, and the experience of Barry the generalist and Jenny the niche Essentialist have been remarkably different. Barry has managed to find two accountants who occasionally refer him clients, although with one the clients aren’t very profitable because Barry had to share a big chunk of revenue with the accountant to get referrals in the first place. His seminar marketing efforts have garnered a handful of clients, but after several years of mailers to the one zip code, all the “good” clients who will respond to a seminar have already come, and the response rate and conversion rate are declining. The articles in the paper and his office location have generated a few occasional inquiries, but most of them turn out to just be kicking the tires or not qualified to do business with him.

By contrast, while it took Jenny some time to get known and liked and trusted in her niche, she now has a great personal relationship with ABC’s HR director, and gets to do a quarterly financial education seminar on site at the company for its employees. And Jenny’s how-to guides have become so popular, the HR director has also begun to distribute them directly to employees, along with the employee benefits packet during the benefits renewal season every fall. As Jenny began to get some retiring ABC Corp employees as clients, she made another guide on how to evaluate the company’s unique partial commutation pension-or-lump-sum option, which she advertises as an e-book on LinkedIn and Facebook to all the company’s employees who are between the ages of 55 and 65. In addition, Jenny has now gotten five of the company’s executives as clients, and is now preparing her next guide, specifically on how to unwind the company’s complex combination of deferred compensation and restricted stock grants. And next week, Jenny has a meeting with a very senior executive for the company, who is interested in not only her services for his personal situation, but wants her feedback about the company’s 401(k) plan.

Notably, after 3 years, the total number of clients and business growth between Jenny and Barry may not be all that different. But their trajectory going forward from here certainly is. Jenny has a growing reputation across the employees as THE go-to person (as she’s written “the definitive guides” that cover most key issues the employees face regarding their employee benefits and retirement elections), and she formed deep relationships with a number of the influential leaders at ABC Corporation (from the HR director to several key executives), who are providing her increasing access to reach the company’s other key influencers and top potential clients. And notably, Jenny can actually spend more and more time marketing herself and networking now, because she’s already invested the time to become such an expert on the details of the benefits the company offers, and she can answer even the most complex client questions off the top of her head. Which is good, because as the increasingly recognized go-to person for the company, Jenny is fieldling a rapidly growing number of referrals as the employees she’s gotten to know through her financial education seminars for the past three years are beginning to call her when their time comes to prepare for retirement.

By contrast, Barry is still struggling to find any momentum; he's fallen into the financial advisor marketing trap of casting a net so wide that he doesn't actually catch very much. His two key accountant relationships continue to provide occasional referrals, but the flow has been haphazard, and they don’t always refer clients who are a good match. In fact, Barry is finding that a lot of people who contact him aren’t a good match, because even as a “generalist” there are limits to what clients he can realistically work with on a profitable basis. And Barry has to screen a lot of the referrals from his existing clients, because some of them aren’t a good match either. In fact, Barry is now spending almost 10 hours per month in meetings with prospects that he can’t actually work with. In addition, while Barry’s seminar marketing efforts have yielded a few clients, their effectiveness is not increasing (as Jenny’s are) but declining as the broad-based mailers get worse response rates. In the meantime, Barry also finds he has less and less time to try to market and network at all, as the demands of servicing his varied client base constantly have him trying to get up to speed on the questions his clients pose; since every question is different from every client, the answers never become routine.

The end point is that, just as McKeown suggested, Jenny’s niche-style Essentialist approach has made it easier and easier to focus and gain momentum and make real progress – at this point, Jenny doesn’t even accept referrals outside of ABC Corp, because she knows that getting ABC Corp clients deepens her relationships in the niche (and they refer her far more anyway), so they’re much more valuable in the long run. And she certainly doesn’t ‘waste’ time on any networking meetings outside of ABC Corp events. Yet at the same time, her work is actually getting easier as she masters the needs of ABC Corp employees, and since Jenny knows when the key issues will arise in her business she feels in control of the business (e.g., October is her busiest time of the year helping employees with their benefits decisions, but knowing this in advance lets Jenny schedule her time and commitments accordingly). By contrast, Barry’s Non-Essentialist generalist approach has left him saying “yes” to everyone, not recognizing that by doing so he’s spread in so many different directions at once he’s not gaining momentum in any of them. Yet he’s taken on so much work to do with existing clients, he’s finding his business is increasingly reactive, as though he’s losing control.

Being An Essentialist And The Paradox Of Success

A key issue that arises in the essentialist approach of focusing in a particular area or niche (or evolving into a niche over time) is that, as success occurs, the very path to success can breed its destruction, in what McKeown dubs the “Paradox of Success”.

For instance, continuing the prior example, imagine how Jenny’s business may evolve in a few more years. ABC Corp is a large company; so large, in fact, that Jenny can’t possibly serve all the employees as clients. Yet now that Jenny is recognized as the go-to expert for the company’s benefits and retirement decisions, a huge number of employees want to work with her. So many, in fact, that now Jenny is struggling just to keep up with all the meeting requests and engagements, which is problematic because some of the clients are really only marginally profitable anyway. In addition, all the inquiries and meetings are beginning to conflict. Last week, Jenny had to decline an opportunity to meet with the company’s newest executive when he was first coming to town, because her day was already booked solid with six meetings of other clients who work for the company – which she didn’t want to cancel, and risk having word get out on the company’s intranet that Jenny is becoming unreliable.

In other words, the “Paradox of Success” is the phenomenon that the purpose and focus that lets us succeed can actually work so well, that it creates an increasing number of options and opportunities – to the point that it leads to diffused efforts, and what started as an Essentialist focus suddenly has more and more Non-Essentialist characteristics. The momentum of success can actually undermine future success!

Accordingly, this is why McKeown emphasizes that Essentialism is not just about taking a moment to sit down and try to gain focus, but is about a continuous way of being to maintain and evolve that focus. Which means a constant process of prioritizing and re-prioritizing what matters most to continue to move forward. In fact, McKeown suggests an exercise of taking everything that you currently do, rank its priority on a scale of 0-10… and then simply stop doing everything that isn’t a 9 or a 10. The approach, while ‘harsh’, forces you to really consider where you’re spending your time and whether you’re spending it on what is most essential. And of course, if the process is repeated periodically, you may find that something ranking high in the past no longer deserves the same score now, given how your business and career (and life) have evolved.

In fact, learning how to cut – Essentialism is the disciplined pursuit of less, after all! – will probably be the biggest takeaway, and biggest challenge, for most who read the book. Yet McKeown suggests that in practice, giving yourself permission to say “no” and be more selective in what you can do is itself very freeing; for most of us, we fear that saying no will make people dislike us, but in the end the fear of saying no is usually just in our heads (as McKeown notes, in reality most people will respect you more for a willingness to say “no” to what you’re not really ready to focus on). And sometimes, the cutting process must be even more aggressive; just as we can accumulate a lot of “stuff” in our clothes closets over time, and periodically must clean the closet out (and really consider what should be thrown away because we’re never really going to wear it again), so too is it necessary to occasionally prune our own activities and commitments, freeing up space to focus on the best new opportunities instead.

In the end, the fundamental point of Essentialism is that we can’t really have success make our highest contribution towards the things that really matter, until we give ourselves permission to stop trying to do everything and allow ourselves the opportunity to really focus. Having real success and impact requires that we live by design and be proactive in prioritizing our lives, or recognize that external circumstances will do it for/to us! For most, it’s scary to say “no” for fear of what we’re giving up, but as McKeown points out, the key is to use that time to think about what you could “go big” on, instead!

In the end, the fundamental point of Essentialism is that we can’t really have success make our highest contribution towards the things that really matter, until we give ourselves permission to stop trying to do everything and allow ourselves the opportunity to really focus. Having real success and impact requires that we live by design and be proactive in prioritizing our lives, or recognize that external circumstances will do it for/to us! For most, it’s scary to say “no” for fear of what we’re giving up, but as McKeown points out, the key is to use that time to think about what you could “go big” on, instead!

So what do you think? Do you find validity to McKeown’s “Essentialism” concept? Is it time to clean out your closet of life and business and do some “pruning” to improve your focus? Does your business operate like an Essentialist niche or as more of a generalist? Are you thinking about changing it now?

Great stuff, Michael. I think you can also apply Essentialism’s principles if you wake up and find you have followed the Barry the generalist path to date (as many of us have). A generalist can follow the “disciplined pursuit of less” by tightening up the psychographic profile of who he/she works with. One of the most professionally fulfilling exercises I’ve had was the first time I asked a good client for a “divorce.” He was a retired pilot and just didn’t fit my ideal client profile, who is far more likely to delegate vs asking what Chinese small cap ETF we should buy THIS week… When my world didn’t crumble, I had the realization that there are far more people who fit my target profile than I could ever help, so no need to stray from it. One can evolve towards a more true niche practice from there.

I had the chance to hear Greg speak at a conference recently. His concept is certainly one worth considering. Although, I see many advisors who are unwilling to focus on the essential if it means they may have to give up some “potential” revenue stream. I think that’s why you still see so many advisors reluctant to pursue a niche market in earnest. It’s tough to say no.

A reminder that 20% of your clients, will provide 80% of your revenues.

Focus on and grow your 20%.

Good job Michael. I just bought our whole team a copy of essentialism. We are taking this approach with our strategic planning.