Executive Summary

Historically, estate planning centered on tangible documentation – wills, account access, and critical information stored in safes or files, with clear instructions for heirs. However, as assets and personal information have become increasingly digitized and moved online, ensuring smooth access to digital accounts has become increasingly complicated. Digital assets range from email accounts and social media to online banking and cryptocurrency – essential elements of daily life that are often trapped behind passwords and authentication barriers. As a result, integrating digital assets into estate plans has become a crucial part of an advisor's process.

Digital assets encompass a wide range of online accounts and property, from financial holdings to sentimental items like photographs and digital media libraries. While cryptocurrency is the most well-known example, even loyalty rewards and social media accounts hold personal and financial value. Yet, contrary to popular belief, providing heirs with usernames and passwords – while crucial – may not be enough.

Because platform privacy policies often dictate how digital assets are handled after a person's passing, unauthorized access can create serious legal and security concerns, including identity theft and privacy law violations. Unlike traditional assets, which are governed by established inheritance laws that dictate how they are handled after a person dies or becomes incapacitated, digital assets often fall under individual service providers' terms of service. Given these risks, it's essential that estate plans include clear, legally recognized instructions for accessing digital assets.

Advisors can help clients navigate this process with a blend of strategic conversations and technology. First, they can help clients create a comprehensive inventory of digital assets, from banking and email accounts to cloud storage and loyalty programs. Next, ensuring that provisions about digital assets are added to the will or trust are key – especially as regulations may allow wills and trusts to supersede a platform's ac–cess restrictions. Once digital provisions are in place, advisors can help clients store this information securely in a digital vault, making it easily accessible to heirs. Finally, maintaining – and periodically reviewing – an up-to-date estate plan that provides for digital assets ensures continued access and security as rules, accounts, and assets evolve.

Ultimately, the key point is that digital assets are a critical but often overlooked aspect of estate planning. When digital assets are given the same attention and care as physical assets, clients and their heirs can have greater peace of mind that their digital legacies will be preserved and transferred smoothly as well!

Let's consider a common – but overlooked – problem in estate planning. A client becomes incapacitated and has essential personal and financial information stored in an online account. The password is secured in a note on their phone, and the phone is locked with a passcode. Even if someone gains access, the note itself requires two-factor authorization that goes to an email account with its own password. Suddenly, what seemed like a simple matter of accessing important information has suddenly become a complex, digital maze!

This scenario isn't unrealistic. As our lives become increasingly digitized, often behind multiple layers of security, the ability to access this information easily also becomes increasingly important. Yet, many people don't think about what will happen to these digital assets if they pass away or become incapacitated, especially when many people don't realize how much we rely on them.

Often, when we hear the term "digital assets", our minds tend to think about cryptocurrency. However, the reality is that these assets encompass a much broader scope, from email accounts to social media to online banking – these are all things that are central to our daily lives. And as society has become increasingly reliant on online platforms, we have unwittingly placed large portions of our lives behind passwords and authentication barriers.

According to the Bryn Mawr Trust 2024 Digital Assets Survey, Americans overwhelmingly report owning digital assets, yet only 29% feel knowledgeable about them. 79% of Americans say protecting digital assets is important, yet only 44% of those with financial advisors say the topic has ever come up in a conversation with their advisor. Surprisingly, among high-net-worth individuals – who, on average, estimated the value of their digital assets at nearly $1M (and who are more likely to have legacy concerns with digital assets) – only 36% reported that their financial advisors had ever discussed the issue with them. Despite having more at stake, these wealthier clients appear to be even less likely to have had conversations about digital estate planning!

The question isn't just who will be able to access these essential digital accounts, but how. And in some cases, whether they should be able to access this information at all. Knowing how to give access to loved ones after something happens to us — whether through permissions or a ‘kill switch' — is a fundamental part of every estate plan.

What Are Digital Assets, And How Does The Law Treat Them?

"Digital asset" is a broad term that encompasses a wide range of account types and online property. Some of the most widely recognized digital assets include cryptocurrency, social media accounts, personal photos and videos, digital music or movie libraries, and even gaming content.

Cryptocurrency, like Bitcoin, is perhaps the most recognizable digital asset due to its financial value and clear standing as an "asset" (and it is what the IRS would most prominently consider a digital asset). However, digital assets extend beyond just financial holdings. Social media accounts, for example, may hold intangible but significant value in terms of personal connections, followers, and potential business revenue. Photographs, videos, and digital files may carry sentimental value or could even be monetized for their content, while music and movie libraries, often purchased via platforms like Apple or Amazon, are part of an expanding universe of digital media ownership. Even less obvious assets, such as loyalty rewards (e.g., frequent flier miles or credit card points), can have significant monetary value.

Essentially, any asset that is stored in a digital format and provides value to its owner – whether emotional, functional, or financial – can theoretically be considered a digital asset. Unlike physical assets that are governed by long-established and routinely maintained laws, digital property poses unique challenges for traditional estate planning because they don't always fit neatly into the existing legal frameworks. And because the concept of digital assets is quite new, the law has been slow to adapt when it comes to establishing consistent rules relating to their ownership and succession.

Further complicating matters, each platform or service provider may have its own rules and terms of service relating to access to site information, whether dealing with cryptocurrency, social media, or digital media accounts. This can complicate efforts to access, transfer, or manage digital assets after an owner passes away. And to make matters worse, there isn't much consistency across providers as to the rights of fiduciaries or heirs to access a deceased individual's digital assets. Some platforms prohibit access or transferability, while others may require extremely burdensome authentication procedures before providing access. This lack of uniformity makes it difficult to plan for and manage digital assets after an owner passes away.

Given these complexities, proactive planning is essential. Individuals should take steps to ensure their digital assets are properly accounted for and managed according to their wishes. This includes taking inventory of digital assets, using secure digital vaults to store login credentials, and making sure that estate planning documents specifically address the accessibility of digital assets.

Primer On The Statutory Landscape On Digital Assets

For many years, laws governing digital assets were either non-existent or outdated, as they did not anticipate the prevalence of online accounts, cryptocurrencies, or other forms of digital property. As a result, the management of these assets often depended on private, platform-specific policies, which varied greatly from one provider to another. These policies, often found in the Terms Of Service Agreements (TOSA), dictate how accounts and digital content are accessed, transferred, or closed. However, they do not necessarily align with traditional laws relating to asset ownership and succession.

To address these gaps, lawmakers have introduced legislation over the past decade to provide clearer rules for the ownership and access to digital assets after an account owner's death or incapacity.

The Evolution of Digital Asset Laws: From UFADAA to RUFADAA

In 2014, the Uniform Law Commission drafted the Uniform Fiduciary Access to Digital Assets Act (UFADAA), to give fiduciaries – such as executors and trustees – the authority to access and manage digital assets upon the owner's death or incapacity. However, UFADAA was widely criticized for its broad scope and privacy concerns, leading to its passage only in Delaware.

In response, a revised version, the Revised Uniform Fiduciary Access to Digital Assets Act (RUFADAA), was introduced in 2015 as a more balanced alternative. Unlike UFADAA, which essentially gave fiduciaries unlimited access to digital assets, RUFADAA limited their access and prioritizing individual control over the disposition and access to their digital assets. The law allows users to designate who can access to their digital accounts through specific provisions within their estate planning documents. Since its introduction, 47 states have adopted RUFADAA (as of February 2025), making it the dominant legal framework for digital asset management.

How RUFADAA Governs Digital Asset Access

RUFADAA establishes a clear order of priorities for fiduciaries seeking access to a client's digital assets, depending on the specific circumstances of the digital asset and platform policies. It provides a three-tiered approach for fiduciary access to digital assets:

- Through the service provider's "online tool";

- Through the user's consent during their lifetime; or

- Through a court order.

The "online tool" (the official term used in RUFADAA) represents the primary authority for determining what controls the disposition and access to a person's digital assets. Many major service providers, such as Google and Facebook, offer tools that allow account holders to designate a person who will be able to access, manage (or even delete) their digital accounts if they become inactive. This tool is often integrated into the account settings or privacy section of the user's online profile options.

For example, Google's "Inactive Account Manager" allows users to specify what happens to their account and data if it becomes inactive for a certain period, including giving trusted contacts access to certain files or deleting the account.

If a service provider offers such an online tool (and the owner uses it), then the user's elections take precedence over the owner's estate planning documents as well as the provider's own Terms Of Service Agreement (TOSA). Unfortunately, not many providers offer such online tools, leaving users subject to the service provider's TOSA, many of which strongly favor the service provider (since, of course, they drafted them) and prohibit access by third parties, even in the event of death or incapacity.

Further, even though online tools can override a provider's TOSA in many cases, comprehensive estate planning documents are still critical. A well-drafted will or trust that specifically addresses digital assets and provides guidance on the right to access such assets plays a critical role in ensuring that the transfer of digital property is seamless and aligned with the individual's wishes.

For instance, if an individual provides specific instructions regarding their digital assets in a valid estate planning document (e.g., naming a digital fiduciary in a will, power of attorney, or trust), those instructions could theoretically take precedence over the TOSA in the event of the individual's death or incapacity. In the absence of such instructions, RUFADAA allows fiduciaries to request access to digital assets through the online platform, provided the platform permits it. The law also ensures that service providers – such as social media platforms, email providers, and cloud storage companies – provide access when appropriate, following the decedent's wishes or instructions as outlined in the relevant estate planning documents.

Accordingly, service providers are required to provide a fiduciary access in certain cases, such as when a trustee needs to access digital assets held in a trust, or when a user explicitly consents to access in an estate plan or online tool. However, access may be denied if restrictions in the provider's TOS or privacy laws apply.

Granting Access To A Trustee Managing Digital Assets Held in Trust. If a digital account is owned by a trust and the trustee is the original user of the account, then the service provider is required to grant fiduciary access. However, if the original account holder was someone other than the current trustee, then RUFADAA outlines a process for obtaining access. This process includes providing the account custodian with the following documentation:

- A written request for disclosure (in physical or electronic form);

- A certified copy of the trust instrument or a certification of the trust (such as under Uniform Trust Code Section 1013) that includes consent for disclosure of the digital asset to the trustee;

- A certification by the trustee, under penalty of perjury, affirming that the trust exists and they are its current trustee; and

- If requested by the custodian:

- The account's unique identifier (such as a username or subscriber number); or

- Evidence linking the account to the trust.

While this process theoretically enables streamlined access to digital assets, many service providers lack a mechanism that allows an account to be owned by a trust, which can limit practical access.

Granting Access To Users With Explicit Consent In An Estate Plan Or Online Tool. If a deceased individual used a service provider's online tool (e.g., Google's Inactive Account Manager or Facebook's Legacy Contact) to grant an authorized person access to their data, the provider is legally bound to follow those instructions – even if they conflict with the user's estate plan or the provider's TOSA.

Similarly, if the user did not set preferences in an online tool but explicitly granted access in a legally valid estate plan (e.g., a last will and testament or power of attorney), the service provider generally must comply with the fiduciary's request.

Denying Access To Fiduciaries. Service providers may refuse access to digital assets under certain conditions, such as:

- The user did not give explicitly authorize access in an online tool or legally valid estate plan documents, and the service provider's TOSA explicitly restricts fiduciary access.

- The request violates Federal privacy laws (e.g., the Stored Communications Act).

- The fiduciary is seeking access to the content of electronic communications (e.g., emails, messages, etc.), which may require additional documentation or even a court order.

RUFADAA represents an important step toward standardizing a legal framework for managing digital assets and ensuring that fiduciaries have the tools they need to fulfill their duties in administering a decedent's estate. However, the inconsistencies between service providers and the lack of universal adoption still pose challenges. Given these complexities, individuals must take proactive steps – such as leveraging online tools and updating their estate planning documents – to ensure their digital assets are handled according to their wishes.

How Access To Digital Assets Differs From Traditional Assets In A Client's Estate

The process for dealing with a digital asset in the event of death or incapacity can be vastly different from handling more traditional assets like real estate or financial accounts. In the case of non-digital assets, the law is robust and generally provides a clear pathway for owners to understand what may happen to the asset if they were to die or become incapacitated. Digital assets, on the other hand, are governed by platform-specific policies and complex security measures rather than well-established legal frameworks.

For example, in the case of a brokerage account, the account owner can reasonably expect that if they were to become incapacitated, their appointed agent under a power of attorney would be able access the account and manage the funds. And if the owner were to die, the account would pass to their named beneficiary under a Transfer On Death (TOD) designation or pass through the probate process if no beneficiary was selected. By contrast, digital assets lack a straightforward process for transferring ownership or access (e.g., through TOD designations, joint ownership, powers of attorney). Instead, each platform dictates its own access rules, which often require navigating through cumbersome authentication processes that involve passwords, encryption, and two-factor authentication. This makes the access and management of digital assets considerably more complex than handling traditional assets, as estate planners and family members must understand the varying rules of each platform and may need legal intervention to gain access.

What Happens To Digital Assets When Someone Dies Or Becomes Incapacitated?

When it comes to digital assets, the TOSAs set forth by online platforms often take precedence over traditional estate and property laws in determining how those assets are handled. Many platforms, whether they involve online banking, social media, or email service, impose their own rules on how users can access, transfer, or dispose of digital assets upon the user's death or incapacity. These terms of service may include clauses that restrict the transfer of digital assets, mandate specific procedures for account access, or even terminate accounts.

In many cases, these platform-imposed rules supersede local or Federal laws that would otherwise govern the distribution or transfer of digital property. For instance, many social media platforms may not allow for the transfer of a deceased user's account or content. As a result posts, messages, and other digital records may become permanently inaccessible to heirs.

Given these complexities, users must be proactive in planning for their digital assets. Users should review platform policies and understand the legal implications of platform-specific rules before assuming that their digital assets will be treated in accordance with traditional property laws or even their estate planning documents.

The Legal Risks Of Accessing Digital Assets Without Authorization

A common assumption when planning for digital assets is to "just make sure your loved ones know your user name and password – that way they can easily log in if something happens!" However, sharing sensitive login information not only presents legal complications for the person who logs in, but it also raises serious security concerns. If a recipient of essential online credential information misplaces or mishandles the information, it could result in unauthorized access or even identity theft, exposing the deceased's or incapacitated person's sensitive data to bad actors.

Additionally, this approach can have serious legal consequences.. Many digital platforms have strict policies regarding the protection of account data, and unauthorized access can result in civil or criminal penalties, depending on the nature of the access and the platform's terms of service.

For example, if someone attempts to log into a deceased person's online accounts without prior authorization that is legally valid, they may be in violation of the TOSA that governs the platforms. Many TOSAs explicitly prohibit a third party from accessing a primary user's account, and some may classify unauthorized access as a form of fraud or identity theft. This could lead to the platform blocking the account, or worse, legal action.

If the account contains sensitive data (e.g., financial accounts, medical records, or personal communications), unauthorized access could also result in privacy law violations. For example, accessing protected health information without proper authorization could violate the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA), potentially exposing the individual to significant legal liability, damages, and penalties. In more severe cases, unauthorized access to digital accounts may even be considered a criminal offense, violating such laws as the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act (CFAA) or similar state-level statutes.

Given these risks, it is critical that clients include clear, legally recognized instructions for accessing their digital assets in their estate plans. Using the proper legal channels can help fiduciaries avoid potential liability while ensuring the individual's wishes are honored. Estate planning tools that can facilitate legal access, such as powers of attorney, digital vaults, and specific provisions in wills and trusts, can help ensure that access is granted securely and legally while honoring the individual's wishes.

How Major Online Platforms Handle Digital Asset Access After Death Or Incapacity

Different online platforms have varying policies regarding digital asset access after a user's death or incapacity. These can range from allowing the user to designate legacy contacts in the event of emergency to enforcing strict non-transferability rules that can make it difficult – or even impossible – for loved ones or fiduciaries to retrieve important digital information.

Below is a breakdown of how some of the most popular online platforms handle digital asset access.

Apple

Apple offers a Legacy Contact feature, allowing users to designate a trusted person who can access their Apple ID data after their passing.

Requirements for Access:

- The Legacy Contact must have an Access Key, which is generated at the time of designation.

- A death certificate is required to submit an access request.

What Can Be Accessed:

- Photos, notes, and emails.

- Purchased content (e.g., music, movies, subscriptions) cannot be accessed or transferred.

If No Legacy Contact Is Assigned:

- Apple requires a court order to grant access to the deceased user's account.

Amazon

Amazon has a strict non-transferability policy for user accounts, meaning account access cannot be passed on after death.

Key Restrictions:

- Accounts are non-transferable, and digital content cannot be inherited.

How to Request Account Closure:

- Family members can request to close the deceased's account by emailing Amazon and providing the following information:

- The account holder's name and email address.

- A death certificate.

- Their relationship to the deceased.

Facebook allows users to plan their digital legacy through memorialization settings, offering two options: appointing a Legacy Contact or opting for account deletion after death.

Legacy Contact Features:

- A Legacy Contact (designated in Facebook account settings) can:

- Manage a memorialized account.

- Update the profile picture.

- Approve new friend requests.

- Limitations: Legacy Contacts cannot access private messages.

Account Deletion Options:

- Users can choose to have their account permanently deleted upon death instead of memorialized.

How To Request Account Memorialization:

- Family members can request memorialization by providing a death certificate.

Google allows users to plan for account access after death through its Inactive Account Manager feature.

Account Planning Options:

- Users can pre-designate trusted contacts who will receive access to their Google data if the account becomes inactive for a specified period.

If No Inactive Account Manager Is Set:

- Google will work with the decedent's "family members and representatives" to determine whether access can be granted.

American Airlines

American Airlines' AAdvantage program has a strict policy regarding account termination upon death.

Standard Policy:

- Upon a member's death, the AAdvantage account is terminated.

- All accrued miles and Loyalty Points are forfeited.

Possible Exceptions:

- In limited cases, and at American Airlines' sole discretion, miles may be transferred to another individual as specified in satisfactory documentation, which, according to the AAdvantage terms and conditions, may include a copy of the member's death certificate, and a copy of an official document establishing the legal authority of the individual.

JetBlue:

JetBlue's TrueBlue points are stated to be non-transferable; however, the Terms & Conditions do not explicitly cover account closure or access for deceased members.

Methods To Help Clients Address Digital Assets In Their Estate Planning

As digital assets become an increasingly integral part of modern life, addressing them in an estate plan has become a necessity. Clients should take proactive steps to ensure that their digital assets are properly managed and transferred according to their wishes.

There are several methods to help clients incorporate digital assets into their estate planning, discussed next.

Make An Inventory Of Digital Assets

Clients should begin by compiling a detailed, comprehensive inventory of their digital assets. This includes:

- Social media accounts (LinkedIn, Facebook, Instagram, etc.)

- Email accounts (Gmail, Outlook, Yahoo)

- Cryptocurrency holdings (wallets and exchange accounts)

- Digital media libraries (Kindle, iTunes, Amazon Prime)

- Loyalty rewards and airline miles (frequent flier miles, credit card points)

- Cloud storage accounts (Google Drive, Dropbox, Microsoft One Drive iCloud)

- Online banking and investment accounts

Creating this inventory will provide a clear picture of the assets that need to be addressed in the estate plan.

Including Specific Provisions In Estate Planning Documents

Including provisions in a will or trust about digital assets is crucial because RUFADAA states that these instructions can override a platform's TOSA. Many online platforms have strict terms that limit third-party access, even for executors or trustees. However, under RUFADAA, individuals can explicitly authorize fiduciaries to access, manage, or transfer digital assets through wills, trusts, or powers of attorney, ensuring their digital property is handled according to the individual's wishes. Without these provisions, loved ones may face unnecessary legal hurdles or even lose access to valuable or sentimental digital property.

If a client created their estate plan more than a decade ago, it is likely that no provision for digital assets exists in the language of their documents. While such provisions are now commonplace, older estate plans without this language may default to the platform's TOSA, which can leave the fiduciary stuck with no access to the individual's accounts, as TOSAs typically deny access to anyone other than the account owner themselves.

Accordingly, we have reached a point where there is no reason not to include a digital asset provision in a client's will, power of attorney, and/or revocable trust. Failing to do so would likely subject a client's fiduciary to unnecessary burdens, forcing them through lengthy legal processes to access important digital assets.

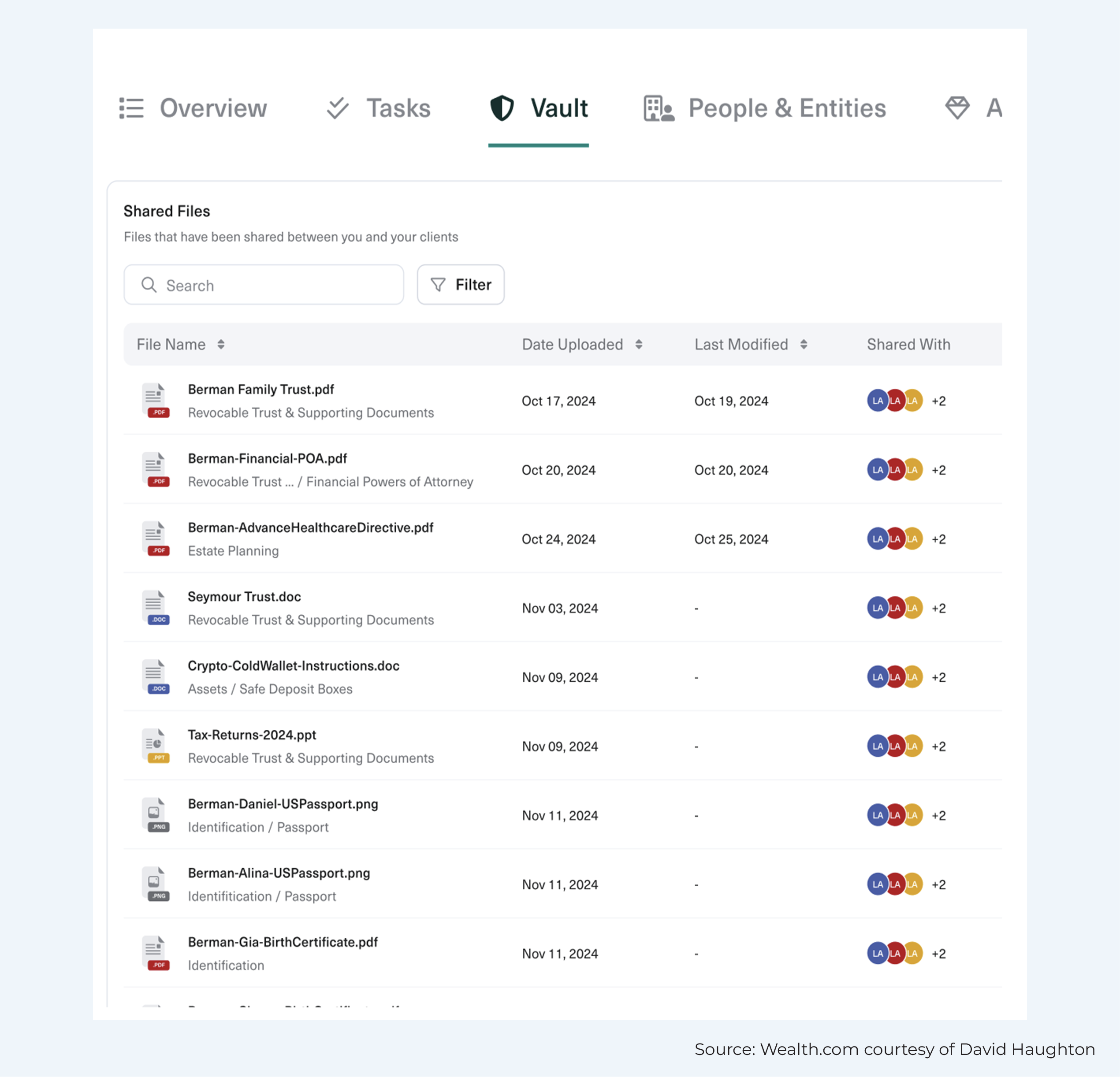

To determine if a client's estate plan includes provisions for digital assets, advisors can review estate planning documents manually or collaborate with attorney COIs for assistance. Additionally, digital platforms like Wealth.com also provide efficient AI-powered tools that streamline this process. These tools permit users to upload estate planning documents and, within moments, extract key details with linked citations, allowing advisors to quickly verify relevant provisions.

A standard digital asset provision in a last will and testament providing a fiduciary with the power over digital assets could appear like the following provision contained in documents created through Wealth.com:

To access, download, control, copy, maintain, sell, distribute, delete, dispose of, or otherwise deal with electronic devices, loyalty programs, digital assets (such as digital currencies) and digital accounts, and any other form of electronically stored information, including electronic photographs and images, audio and video files, electronic mail, documents and calendar, social media and digital storage accounts, and software licenses, online communications or hosting services, as that term is understood in the Stored Communications Act or any relevant state law;

Using Digital Vaults

In addition to updating documents, digital vaults have become an important resource for securely storing critical information, including account passwords, insurance policies, medical records, and other vital documents. These secure, encrypted vaults are designed to hold sensitive data, offering both easy access for designated individuals (such as a trusted executor or family member) and a safeguard against unauthorized access.

One of the key benefits of using a digital vault is that it centralizes all of the necessary information in one protected location, ensuring a smooth transition of assets in the event of incapacity or death. However, it's crucial that these vaults are managed carefully, with clear instructions on how and when authorized users can access the information, preserving the security of both digital and traditional assets. Integrating digital tools and vaults into the estate planning process can provide peace of mind, knowing that crucial documents and passwords are safely stored, easily accessible, and regularly updated to reflect any changes in the estate holder's circumstances or wishes.

For example, Wealth.com offers a digital document vault were clients can securely upload and store critical information and documents. Typically, financial advisors are granted access upon upload, as many of these documents are integral to the client's estate and financial plan. . Additionally, users may grant emergency access to specified individuals – such as family members or trusted friends – in the event of death or documented incapacity (i.e., verified through medical documentation). These digital vaults feature strong security and encryption, providing a secure estate planning tool that protects documents while reducing the risk of loss or theft.

Various providers offer highly encrypted systems designed for storing sensitive legal, financial, and medical documentation, as well as passwords. . These platforms are designed to enhance security and accessibility, ensuring that critical information remains protected and available when needed.

Leveraging Online Tools

Because the law generally recognizes a service provider's "online tool" as the preferred method for granting successors access to digital accounts in the event of death or incapacity, individuals should review the features and TOSAs of the platforms where they hold their most precious accounts. If an online tool is available, they should use it to designate a successor who can manage or access the account. While not all platforms currently offer this feature, its adoption is growing and it may soon become more common among major service providers over time. Taking advantage of these tools now can help prevent unnecessary legal hurdles and ensure that digital assets are handled according to the owner's wishes.

As digital assets play an increasingly significant role in clients' lives, ensuring that they are properly accounted for and managed in their estate plan is critical. Some platforms provide structured tools for managing digital assets, while others impose strict policies that limit access after death or incapacity.

Without proactive planning, heirs and fiduciaries may face substantial obstacles when trying to access a deceased individual's digital assets. To safeguard their digital legacy, individuals should review platform policies, include digital asset provisions in their estate plans, and take advantage of online tools where available. These steps can help ensure that digital legacies are managed – and protected – according to their wishes, while reducing potential complications for loved ones at the most difficult of emotional times. With the right planning, what matters most – whether financial, sentimental, or personal – can remain accessible and preserved for future generations.

Leave a Reply