Executive Summary

Now with more than $2 trillion in assets, the exchange-traded fund (ETF) has exploded onto the investment scene in the past 20 years, with the bulk of the growth occurring even more recently, built on the base of popular ETF features from their tax efficiency to relatively low cost to their ability to trade intra-day like a stock (and unlike a traditional mutual fund).

Yet ironically, in recent weeks the popular feature of being able to trade intra-day has turned into a liability instead, as market volatility has triggered a number of extreme (but short-term) situations where ETFs have traded at a significant discount to their intrinsic net asset value, in some cases as much as 30% below intraday NAV for an hour or few at a time.

For those advisors and investors who trade infrequently anyway, this kind of intra-day volatility may be a “non-issue” that was literally not even noticed by those who owned the ETF securities. Except those who panicked and sold at the market’s open based on overnight news. Or, unfortunately, those who were using Good ‘Til Cancelled (GTC) stop loss market orders.

In fact, the recent volatility of ETFs highlights that when it comes to using stop loss orders in particular, advisors and investors must be especially careful about how those trades are structured, in a world where ETFs with ‘temporary’ bouts of illiquidity can trade at dramatic discounts. At a minimum, those who wish to continue to use stop loss orders as a form of risk management may seriously want to consider using stop loss limit orders instead, with a gap between the stop loss and limit thresholds that is wide enough to still trigger a sale when the underlying NAV is falling, but reducing the risk of triggering a market sell order at the nadir of an ETF’s short-term “flash crash” price!

ETF Intrinsic Intraday NAV And Price Arbitrage Through ETF Creations And Redemptions

One of the unique features that has made the exchange-traded fund (ETF) so popular is the fact that, unlike a traditional mutual fund, ETFs trade throughout the day like a stock. This allows both traders and investors to try to execute their purchases and sales more effectively on an intra-day basis, unlike with a mutual fund where the trade price will be based on the Net Asset Value (NAV) of the underlying securities at the close of the market.

On the other hand, the fact that mutual funds only trade at the end of the day at their closing NAV price does ensure that the mutual fund will process buy and sell orders at that exact NAV price. Mutual fund buyers and sellers still need to decide which day to buy or sell to achieve their investment goals, but they don’t need to worry about whether the trade will be executed as the representative price tied to the underlying shares.

By contrast, since ETFs are technically traded as a “wrapper” around the underlying securities they own, ETFs can be traded at prices that differ from the net asset value of the underlying securities themselves. As a result, the actual market value purchase or sale of an ETF may be at a price premium or discount to its “intrinsic NAV” (or “intrinsic ETF value”).

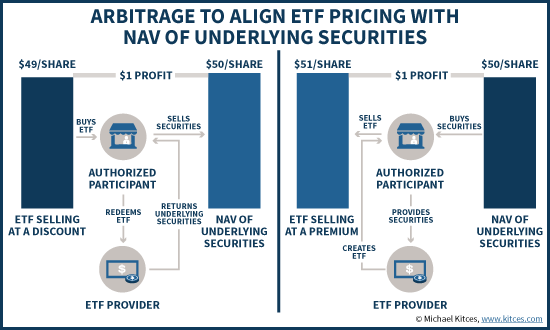

Fortunately, though, in practice the market price for trading most ETFs rarely deviates by much throughout the day from its underlying intraday NAV (or iNAV). The reason is that, even though technically the ETF itself and its underlying securities are two different investments that have different asset flows and buy/sell demand, any material deviation between the two creates an arbitrage opportunity; if an ETF is valued at a material premium above its NAV, an arbitrageur can short the ETF and buy all the underlying stocks OF the ETF, and simply wait for the prices to converge to earn a profit. Conversely, if the ETF is priced at a discount, the arbitrageur would buy the ETF and short the underlying stocks to achieve the same result.

This arbitrage process is further expedited by the creation/redemption mechanism of ETFs, which allows authorized participants to actually buy the underlying stocks of an ETF and turn them over to the ETF provider to create a new share of the ETF (or alternatively to turn over a share of the ETF to redeem it and get the underlying stocks). Because ETF creations and redemptions are usually executed in blocks of 50,000 ETF shares (which imposes a significant capital requirement), authorized participants are generally market makers, market specialists, and large financial institutions in the first place.

From the perspective of ETF pricing, these creation/redemption trades make it even easier for arbitrageurs to act and ‘ensure’ that ETFs trade very close to their underlying iNAV throughout the day. Because now the (authorized participant) firm doesn’t even have to buy the ETF at a discount and short the underlying stocks, it can simply buy the ETF at a discount, redeem it, and then sell the shares for their full/fair value to generate a profit (or vice versa by buying the stocks, acquiring 50,000 shares of the ETF, and then selling the ETF at a premium). The sale of the ETF at a premium (or its purchase at a discount) drives the ETF share price back towards its intrinsic value. And of course in today’s modern computer age, these trades can be executed with remarkable speed.

Accordingly, as long as markets remain reasonably illiquid, so authorized participants really can buy/sell the ETFs and/or their underlying holdings to engage in the arbitrage process, ETFs tend to stay in a very narrow trading band around their underlying iNAV all day long. Because if they didn’t, the authorized participants would buy/sell as necessary to earn an arbitrage profit – which in turn, would put the prices back in sync (and notably, this process also helps to deepen the liquidity for ETFs along the way as well).

ETF Price Discounts When Underlying Holdings Become/Are Illiquid

A crucial caveat to the role of authorized participants (and arbitrageurs in general) acting to keep an ETF’s market in line with its underlying iNAV throughout the day is that it only works if both the ETF and the underlying securities are liquid in the first place. If it’s not possible to smoothly trade both, it becomes impossible for the creation/redemption process to facilitate ETF pricing. After all, buying the ETF at a discount to redeem and re-sell the underlying securities isn’t risk-free arbitrage if the underlying securities can’t be sold and the trader would have to sit on them for an unknown period of time (selling them in the future at an unknown and potentially lower price).

Of course, this challenge isn’t entirely new. For instance, it’s not uncommon for ETFs with international holdings to have premiums or discounts to pricing from the apparently underlying NAV, because the foreign markets where those securities trade may be closed when the US markets are open (so it’s not entirely clear what their prices should be, and/or it’s difficult/impossible to trade those underlying securities effectively). In more extreme situations, such as with the Egypt ETF during the Arab Spring several years ago, or the Greece ETF during Greece’s recent market/debt turmoil, the stock exchanges of the foreign countries may be outright closed for a period of time, so it’s only a guess at best about what the underlying NAV even “should” be in the first place!

In other words, a fundamental point – sometimes forgotten by investors given the seemingly infinite and stable liquidity of ETFs – is that in the end, ETFs can’t really be any more liquid than their underlying securities (because the creation/redemption process will ultimately be constrained by the liquidity of the underlying holdings), but since ETFs remain marketable throughout, the potential emerges for what can be significant gaps between the market pricing of ETFs and their (presumed) NAV.

And of course, since liquidity most commonly vanishes during times of market distress, the lack of transparent pricing around the ETF and ongoing selling pressure (and inability to arbitrage away pricing discrepancies) will most likely result in a downwards gap – i.e., that the ETF will trade at a potentially significant discount to its NAV.

ETF Price Discounts During Stock Market Volatility, Rule 48 Openings, And Clearly Erroneous Trade Cancellations

In recent months, a number of organizations have been sounding alarms that investors might be counting too much on the implied liquidity of ETFs while times have been good, forgetting that moments of illiquidity can happen. Given the potential for rising interest rates in particular, earlier this year markets buzzed as ETF providers started taking out huge lines of credit to help support their bond ETF liquidity during potential bond market distress, and more generally Morningstar recently ‘warned’ about ETF liquidity as well.

Yet as it turned out, the most visible bout of illiquid markets disrupting ETF pricing came not amongst bonds, but with “good ‘ole equities” when the markets opened a few weeks ago on August 24th, amidst a prior fears of China’s slowing economy and changes in the Yuan exchange rate that triggered a Friday sell-off that carried through to a somewhat “panicked” Monday opening. In fact, the opening pricing for stocks was so uncertain that Monday morning, the NYSE invoked “Rule 48”, which suspends the normal requirement that stock prices be announced by market makers at open and instead allows them to just start trading directly.

While the purpose of Rule 48 is actually to speed up the opening of markets in the morning (allowing markets to find their own market clearing price faster than a market maker with a significant order imbalance could), in practice a number of stocks and ETFs gapped down at the market open – enough to trigger circuit breakers that almost immediately suspended the trading in those stocks or ETFs. (Circuit breakers for ETFs in particular were instituted in 2010, suspending ETF trading for 5 minutes anytime that the price changes by more than 10% in the preceding 5-minute period, as a way to avoid the computer feedback loops that caused the May 2010 “flash crash”).

Except as it turned out, the fact that various stocks gapped down (triggering individual circuit breakers) and that a number of ETFs also gapped down (again triggering individual [ETF] circuit breakers) meant that on that particular Monday morning, it was almost impossible for arbitrageurs to work their normal ETF “magic” to keep prices in line with their underlying intrinsic NAV. Instead, the illiquidity of the stocks, the ETFs, and their intermittent trading windows (as many were suspended from circuit breakers, re-opened, and then got re-suspended minutes later again) meant that ETF prices diverged significantly. And they actually became so illiquid for a short period of time (with more than 1,200 trading halts in just a few hours that morning), market makers seemed unwilling to make a market in the ETFs either, or at least not without a gargantuan bid/ask spread.

The end result: some “normally” widely traded ETFs ended out trading at massive price discounts to their underlying NAV (at least, when it became clear in retrospect what the underlying NAV actually was). For short periods of time, the iShares Select Dividend ETF (DVY) plummeted as much as 35% (even though its worst-performing underlying stocks were “only” down about 11%), the Guggenheim S&P 500 Equal-Weighted ETF (RSP) was off 42%, and the iShares Conservative Allocation Fund (AOK) was ironically (given its name) off 50% at one point from its Friday close.

Notably, though, while these ETF prices may seem shocking, both for their sheer amount of price volatility from the prior day’s close, and because they (ultimately) were shown to be dramatically different than their underlying intra-day NAV, they were properly executed trades. It’s not as though individual trades occurred at prices that were substantially different than all the other trades occurring at the same time – which could trigger a “Clearly Erroneous Trade” cancellation under NYSE or similar NASDAQ rules. Instead, the trades really were happening at the market price of the ETF at that time – it was just that the market price of the ETF was deviating materially from its underlying iNAV, and due to other market factors, arbitrageurs were not doing the buying necessary to bring the price back up in line; instead, sellers just continued to sell, even at those low prices, creating a buy/sell trade imbalance that continued to drive the prices lower.

In other words, the pricing “abnormalities” of ETFs trading at prices materially different than their corresponding iNAV does not ultimately represent a trade “error”, but simply the reality of ETFs that trade independently of their underlying securities. While in the long run, arbitrageurs can and ultimately do act to bring prices back in line (in fact, most of the aforementioned price discrepancies lasted an hour or few at most, and the SEC is already rumored to be discussing changes to reduce the potential for such significant discrepancies in the future), in the short term an ETF can and will still trade at whatever price the market will bear.

Which means, just like selling any illiquid security in the midst of a market sell-off (whether an ETF or a stock or anything else), if you execute a sale at an ‘unusually’ low price because that’s what the security is trading at under duress, the price you get is the price you get, and if you don’t want that price, don’t trade at that moment!

The Problem With ETF Stop Loss Market Orders In Times Of Illiquidity

For most investors, not trading ETFs in times of volatility (e.g., when ETFs are illiquid) is pretty straightforward: just don’t trade. As noted earlier, the extreme price ‘distortions’ of most ETFs did correct themselves in a matter of an hour or few, once the circuit breakers wound down, market trading returned to normal, authorized participants and other arbitrageurs could begin the normal process of ‘helping’ the ETF price converge on its underlying NAV. So as long as you weren’t just entering outright market orders to sell at the open on Monday, you may never have even noticed the discrepancies! And of course, most experienced advisors taking calls from clients that Monday morning would have been counseling them strongly not to sell in a panic, and certainly (hopefully!?) wouldn’t have been entering market orders to sell (especially upon seeing the quoted ETF price).

However, the problem that did crop up that Monday morning was for investors and advisors who try to manage risk using stop loss orders. Because unless specified otherwise, a stop loss order turns into a market order once the stop price threshold is triggered – which means advisors and their clients really might have been executing market orders to sell at the market’s open!

GTC Stop Loss Market Versus Stop Loss Limit Orders

For those unfamiliar, there are really two types of stop loss orders: a stop loss market (or “sell-stop”) order, and a stop loss limit (or “stop-limit”) order.

In both cases, the idea of a stop loss order is that the sale cannot be triggered until the market price of the stock (or ETF) falls below a specified threshold. So as long as the security remains above the threshold, there is no sell order at all. When the price falls, and crosses the threshold, the sell order is triggered.

In the case of a stop loss market order, once the threshold is crossed, the trade is turned into a normal market order to sell, executed as quickly as possible at the then-current market price.

With a stop loss limit order, on the other hand, once the stop threshold is crossed, the trade is turned into a limit order, which only triggers if the price is above the limit order threshold.

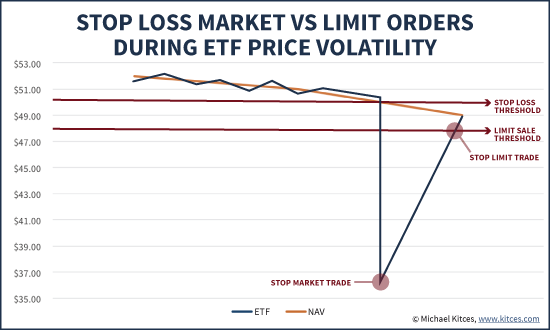

For instance, imagine an investor who owns shares of an ETF that is currently trading at $55/share. He enters a stop loss order at $50/share that is GTC (good ‘til cancelled), meant to ensure that if the ETF ever falls below that threshold in the indefinite future (or until the GTC order is cancelled), the investor will sell the ETF (ostensibly as a risk management tactic, to avoid holding it as it declines even further). If the investor enters a stop loss market order, the trade will simply execute at the first available opportunity the price falls below $50. On the other hand, if the investor enters a stop loss limit order with a stop at $50 and a limit at $48, the investor’s limit order won’t be activated until the ETF falls below $50, but then won’t be executed (as a limit order) unless the price is above $48.

In a world where ETF prices simply decline in a continuous series of $0.01 increments, there will be no difference in the outcome. Either the price will tick down to $49.99 and the stop loss will turn into a market order executed at $49.99, or the price will reach the same point and the stop-limit will turn into a normal limit sell order at $48 and since $49.99 is above $48 the trade will still execute at the then-current price of $49.99.

However, in a world where markets gap down and ETFs can have a “flash crash”, a different outcome may occur. If the previous close of the price was $51, and the investment opens the next morning at $46 (gapping down 10%), a stop loss market order will sell at the $46 opening price, while the stop-limit order will turn into a limit order to sell at $48 with a price at $46, which means it won’t execute until/unless the price gets back above $48! And of course, if the price keeps falling from there, the stop-limit order may never be executed, and the investor could ride the ETF (or stock or whatever) all the way down.

On the other hand, though, in an environment like Monday, August 24th, a very different outcome occurs. Due to the illiquidity issues, the ETF might not have just gapped down from $51 to $46, instead it gapped down nearly 30% to $36 (even though the underlying NAV was still up at $49, down “just” 4%). With a stop loss market order, the trade would be triggered at market, selling at the then-current price of $36. Once ‘normal’ trading resumed an hour or two later, the ETF price would have rebounded close to the NAV of the underlying securities around $49, but by then it would be too late. However, if a stop-limit order had been used with a stop threshold of $50 and a limit threshold of $48, the ETF would have opened at $36 (triggering the stop and activating the limit order, but not executing the limit order because $36 is below the target sales price of $48), and then held until the price rebounded to the $49 NAV (or more accurately, selling as soon as the NAV recovered back over the $48 threshold).

The end result: the stop loss market order would have ended out selling at the bottom in the midst of the illiquid and “distorted” ETF price, while the stop-limit order would have allowed time for ‘normal’ trading to resume, ensuring that any “extremely” distorted temporarily pricing aberrations are resolved before executing the sale. And of course, any investor or advisor who simply wasn’t using stop loss orders at all, and didn’t have any trades pending that day, may not have noticed the issue at all!

Best Practices For Stop Loss Orders With Potentially Illiquid ETFs

Unfortunately, news stories in the aftermath of last week’s volatility have made it clear that there were a number of advisors using stop loss market orders, who really did have trades execute at ‘highly unfavorable’ market prices when several ETFs gapped down (more than their underlying NAVs) at the open, along with a number of computer algorithms that were simply executing sales according to their algorithms (without pausing for a moment to realize how unusual trading activity really was that morning and that taking a time-out for the day might be a good idea!).

When it comes to dealing with individual stocks, there has always been an issue between balancing the risk of using a stop loss market order – where the trade will execute if the stock gaps down – and using a stop limit order where the trade might not execute if the stop gaps down and then will continue to fail to execute as the stock goes all the way to zero.

Yet the caveat is that in general, using stop loss orders with ETFs is fundamentally different than using it with stocks, because an individual stock can keep going down to zero but it’s virtually impossible for a diversified basket of stocks to do so. For instance, while stocks can be rocked by news events, and in theory open at or near zero out of the clear blue sky (or at least, drop by 50% or more), the Dow Jones Industrial Average has only had four days in history where the markets were even down more than 10% (the crash of 1987, once in 1899, and twice [consecutively] during the crash of 1929, and the S&P has never dropped more than 10% in a day outside of the crash of 1987). In other words, even the “worst” days for a diversified holding of stocks is generally nowhere near the “worst” days for an individual stock; and in addition, a diversified basket of stocks (which generally can’t all fail and go out of business at once) has a limit as to how far they can define before their fundamental value takes hold, unlike an individual stock that really can entirely go out of business.

Accordingly, from a practical perspective there is likely far more risk of a stock gapping down through a stop limit order and never being executed, versus the same GTC stop limit order for a (reasonably diversified) ETF. Which means advisors and investors who might have been wary of using stop limit orders for individual stocks should probably still be considering them as a “best practice” for diversified ETF holdings.

Of course, if the limit order is placed too close to the stop loss threshold in the first place, it’s still possible that the trade will never be executed. Continuing the prior example, if the stop loss order was at $50 and the limit order was at $49.50, the trade would never be executed, and if the market continued to fall the investor would still ride the ETF all the way down (however far it fell), which may fail the risk management goal. Thus, it’s necessary to set some ‘reasonable’ gap between the stop loss trigger threshold, and the limit order target.

In turn, it’s also important to remember that the limit order target doesn’t mean the trade will execute at a price that low. In the example earlier, with a stop loss threshold at $50 and the associated limit order at $50, if the ETF had declined in orderly $0.01 trading increments, the trade would have still executed at/around $49.99, not all the way down at $48. In fact, the whole point of a stop limit order is that in an orderly price decline, the trade will occur at/near the stop price, but if the price decline is disorderly and gaps down the trade will not occur until/unless the price rebounds above the limit threshold.

So how wide should the gap be between a stop loss threshold and the associated limit? While there’s no clear rule on this – given that we don’t “know” how volatile prices will be in the future, or how they’ll trend – the history of the markets, where it’s been rare for an index to ever gap down more than 10% (but ETFs can temporarily price as much as 30% or worse below NAV), suggests that a 10% gap might be reasonable. Those who want tighter thresholds, or perhaps are more optimistic that a sharp sell-off will have a sharp bounce, might set a threshold at “just” 5% below the stop loss threshold (though there have been many days in market history where even broadly diversified indices dropped more than 5% so some risk still remains that the price will fall through).

Again, if prices drop in an orderly fashion, the gap will be a moot point, because the trade will get executed near the stop loss threshold, but at least if a larger gap does occur – including because the security is an ETF that is temporarily trading at a discount to its NAV due to market illiquidity – the price must rebound to the limit order before executing. Which means in essence, the goal is to set a stop limit threshold that is wide enough that if the NAV drops the limit order will still trigger, but if the ETF market price drops further than the NAV the ETF trade won’t execute because it’s below the limit threshold. Or viewed another way, the goal is to sell the ETF in real market declines, but not at the temporary bottom of an ETF flash crash.

Of course, for advisors and investors who are more active, the whole approach of “managing risk through stop loss orders” may be unappealing, in part because of these challenges in figuring out where to draw the line for a stop loss order, whether to use a stop loss market or stop loss limit order, and if it’s a limit order to protect against ETF discounts against NAV, how much lower should the limit price be to protect clients? But at a minimum, as long as ETF discounts remain a possibility – and as we’ve seen recently, they not only can occur, but with perhaps even more of a “discount gap” than most ever anticipated – stop loss limit orders with some lower brand to protect against a badly timed execution in the face of extreme illiquidity seems appealing.

And for those who really are longer term investors, and don’t have any need to consider market orders or limit orders to sell in a market decline, and instead view these as buying opportunities… well, these short-term ETF price discounts may simply be even better buying opportunities in the first place!

So what do you think? Has the recent price volatility of ETFs made you more wary of using them? Did you have stop-loss orders trigger unexpectedly on Monday August 24th of 2015? Will you be changing your stop loss strategy to use stop loss limit orders instead?

Michael, I think once again I am amazed at the incredible quality and science that you continually provide for your readers! You bring forward so many quality ideas and deep knowledge of the products in the ETF Space that I have read about (Thinking Rick Ferri and ‘All About ETF’s”) but I had not thought about these products in light of the increased volatility of the past 2.5 weeks. I still do not personally own an ETF but study the product including strengths and weaknesses vs their competition.

Why not take this “problem” and turn it into a huge opportunity? Personally, I went to bed that Sunday night thinking about the May 2011 “flash crash” and the problems it created for these potentially illiquid ETFs. Monday morning I woke up looking for the “problem children,” found a few, and entered large block orders to buy at the severely discounted prices. Only one order was filled, but it resulted in a 20% one-day gain for clients when I sold the next morning. I realize now I should have been even more aggressive (and will be should the opportunity present itself again- which I think it will)

My portfolio realized a 10% loss in a matter of minutes on Aug 24, 2015. It still burns to think about it, have been investment shy since. Your graph sums up exactly what happened. The stop loss instruments I used to protect myself burnt me worse than I could have imagined. Some of my ETF’s executed sales at the trough, >-30%. Within minutes the same ETFs corrected. Thanks for your article, I may reconsider investing again using the stop loss limit orders you describe.

I appreciate, cause I found just what I was looking for. You have ended my 4 day long hunt! Now I am reading 2 blog one of your other one is a3trading God Bless you man. Have a great day. Bye with thanks.