Executive Summary

The ongoing decline of defined benefit plans and pensions, and the associated rise of defined contribution plans – in the US and around the globe – is leading to a growing body of research around how best to “de-cumulate” a lump sum of assets after they have been accumulated in the first place.

To address the challenge, a wide range of strategies have emerged, some built around a “safety-first” framework of guaranteeing a base of income (e.g., with annuitization or a pension) and building on top of that, while others have focused on a more “probability-based” portfolio-centric approach that aims to spend down the invested assets while maximizing the probability of success along the way.

Yet the reality is that portfolio-based strategies built around a “conservative enough” safe withdrawal rate effectively are a safety-first approach, while safety-based strategies using annuitization or pensions can still have at least some risk (as evidenced by the history of insurance/annuity company failures, and the growing shortfall of the PBGC in backing failed pensions).

Perhaps instead a better way to recognize the range of retirement income strategies is based on whether retirees trust in insurance and annuity guarantees and choose to transfer the risk, or instead “trust” in markets and the equity risk premium in the long run and choose to retain the risk while seeking appropriate strategies to reduce or avoid the danger of a shortfall along the way!

Opposing Retirement Philosophies: Probability-Based vs Safety-First

In a recent new retirement white paper entitled “The Yin And Yang Of Retirement Income Philosophies” (by retirement researcher and professor Wade Pfau, and Jeremy Cooper, the chairman of retirement income for Australian investment and annuity provider Challenger Limited) explore what they have dubbed the “opposing” retirement philosophies of probability-based versus safety-first.

In this framework, “probability-based” planning is about conducting a Monte Carlo analysis to determine that a portfolio is capable of supporting a particular retirement spending goal. The Monte Carlo trials are run, and the plan has a certain “probability” of succeeding based on the percentage of scenarios that achieved the spending without any shortfall (e.g., a 90% probability of success).

In the safety-first approach, by contrast, the idea is typically to ensure that at least some base level of “essential” spending needs are “safely” funded for life – i.e., on a guaranteed basis, precisely matching assets to the future spending liabilities, such as with the purchase of a lifetime annuity, using a pension, or perhaps an ultra-long-term bond ladder.

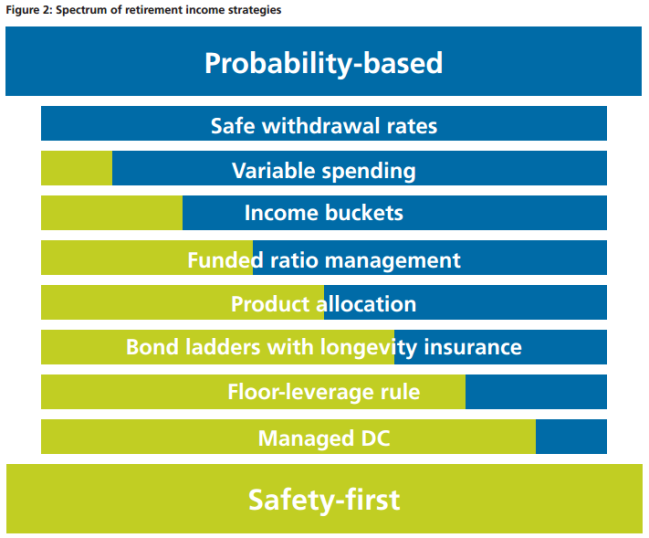

Viewed on this spectrum, Pfau and Cooper then align a wide range of popular retirement income strategies on the basis of whether they tilt more towards a probability-based approach, or a safety-first approach, as shown in the graphic below.

The Probability Problem With Safety First

While Pfau and Cooper’s characterization of which strategies are (and are not) commonly modeled with a probability-based (i.e., Monte Carlo) analysis does reflect common practice today, the problem with such a framework is that ultimately the distinction may be just that – a delineation of common practices today, and not actually a unique and mutually exclusive differentiation in the strategies themselves.

For instance, the whole origin of Bengen’s “safe withdrawal rate” approach (which Pfau and Cooper place into the “probabilistic” philosophy) was to determine a spending rate low enough that it would never have failed at any point in [US] history. In other words, the safe withdrawal rate approach – at least in its original form – was actually designed to be a 100% safety approach, where the “4% rule” spending level could be aligned to “essential” expenses and any upside from there would cover discretionary spending and legacy goals in the exact same manner as other safety-first approaches! While some debate remains about whether 4% is the “right” safe withdrawal rate number, or whether it should be lower (or not) in today’s environment, the point remains that clearly some spending level is low enough that, even if “bad stuff” happens, the retiree has still assured the safety of his/her spending simply by making it conservative enough to whether any storm. In other words, probability-based safe withdrawal rate approaches can easily be safety-first approaches, simply by setting the spending rate low enough to be safe.

Conversely, while strategies like a managed defined-contribution plan are framed as a non-probabilistic “safety-first” framework, the reality is that they are not universally 100% “safe”. In looking at the history of corporate defined benefits plans, the reality is that in the earlier days (the mid-1900s), there were several high-profile defined benefit plans that collapsed, leaving workers without their promised benefits; in fact, the creation of ERISA in 1974, which also established the Pension Benefit Guaranty Corporation (PBGC), were created in the aftermath of these failures, an attempt to reduce their probability of failure. Even so, pension plans continue to have failures, including large high-profile companies like several airlines, which has been so whittling down the PBGC’s assets that the recent Multiemployer Pension Reform Act of 2014 was passed to allow some pension plans to cut their own benefits in an attempt to reduce the severity of their failures for the PBGC!

Similarly, the “safety-first” strategies using various types of bond(s or bond ladders) or annuity products are not entirely “safe” either. Insurance companies do have failures, bonds do default, and not every company has a rating of AAA. In point of fact, data from Moody’s and S&P shows that cumulatively over time, even companies once rated AAA have had some defaults (at least to some extent), and the rate just drifts higher into the AA, A, and lower categories.

| Cumulative Corporate Bond Historic Default Rates | ||

|---|---|---|

| Rating Category | Moody's | S&P |

| Aaa/AAA | 0.52% | 0.60% |

| Aa/AA | 0.52% | 1.50% |

| A/A | 1.29% | 2.91% |

| Baa/BBB | 4.64% | 10.29% |

| Ba/BB | 19.12% | 29.93% |

| B/B | 43.34% | 53.72% |

| Caa-C/CCC-C | 69.18% | 69.19% |

| Investment Grade | 2.09% | 4.14% |

| Non-Invest Grade | 31.37% | 42.35% |

| All | 9.70% | 12.98% |

Granted, while the default rates for highly-rated companies are not high – and in many cases have some further backing for annuitants (with limits) from state insurance guaranty funds – the fact remains that the probability of success is not 100% in the world of most “safety-first” strategies. Especially since not all consumers necessarily purchase from the highest-rated insurance/annuity companies, either!

Similarly, the ongoing discussions about whether Social Security benefits payments may someday have to be trimmed – or face a “forced” cut of almost 25% sometime in the 2030s or so – just emphasizes the point that promised “safety-first” payments can appear entirely “safe” and stable… right up until they’re not.

The key is that just because the risk (and/or the value) of a bond, annuity, or defined benefit plan payment is not continuously adjusted up and down on a daily basis and “marked to market” doesn’t make it unequivocally “safe” either. The odds that everything works out OK using insurance companies and defined benefits may still be highly probable… but that’s still a probability that the insurance/annuity company won’t default. And in fact, given that there is at least some probability any random insurance company might have failed in the past century, while a 4% “safe” withdrawal rate has never failed in US history, the dividing lines of “probability” versus “safety” don’t appear to be mutually exclusive at all! Either can have a probability of failure if spending is too high to be sustainable… or at least, some probability of a required adjustment to get back on track!

Risk Transfer Vs Risk Retention – The Real Difference In Retirement Income Philosophies

So if the key distinction between portfolio-based strategies (which “tend” to be probability-based under Pfau and Cooper) and insurance/annuity-based strategies (which “tend” to be safety-first) is not actually about probabilities versus safety, then what is the distinction? Given that either can potentially have – or manage – risk, what it really comes down to is how the risks are being managed. In other words, the real distinction is about risk transfer versus risk retention.

In risk transfer strategies, the goal and purpose is to shift at least the bulk of the risks to some other entity. Thus, for instance, where the greatest risk for many retirees is living beyond their life expectancy and not having enough money to cover that “unexpectedly” long time horizon, the purchase of annuities and use of a lifetime pension is an effective transfer of longevity risk. Similarly, retirees may also seek to transfer their exposure to market risk to the annuity company through the purchase of (variable) annuities with retirement income riders (albeit in a much less effective manner due to the difficulties in risk pooling with such guarantees and the danger that risk is actually concentrated).

At the other end of the spectrum are strategies that retain the risk, where the retiree manages it directly instead. For instance, safe withdrawal rates are a strategy where the risk of markets and longevity are maintained, and simply reduced by setting a deliberately conservative spending strategy; variable spending or income buckets similarly retain the (market and longevity) risk but mitigate it by dynamically adjusting spending or managing the portfolio in a manner that blunts the exposure. Alternatively, purchasing a bond ladder as a floor seeks to manage at least the market risk by simply avoiding it altogether; although longevity risk still remains, that can at least be reduced by creating a bond ladder with a “conservatively long” time horizon.

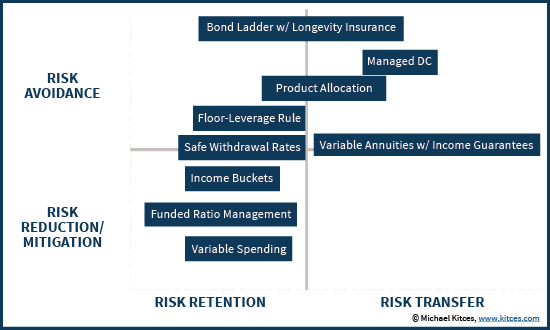

Notably, then, even within the context of “risk retention” there are strategies that seek to reduce or mitigate the risk (e.g., dynamic spending or safe withdrawal rates), while others that simply try to avoid the risk (e.g., using bond ladders for an arbitrarily long-past-life-expectancy time horizon). In fact, we can re-graph the spectrum of strategies that Pfau and Cooper examined on this basis, which puts the strategies in substantially different context.

As the chart reveals, the real distinction in most retirement income strategies is whether the risks (primarily of the market and of longevity) are retained and either reduced/mitigated or just avoided altogether, or instead are transferred to an insurance company as a means of (at least mostly) avoiding them. Though as noted earlier, even transferring the risk still ultimately retains some probability that the entity being transferred to will itself not be able to make good on its promises!

Retirement Income Philosophies – Who/What Do You Trust, Markets Or Guarantees?

Given that the key differentiator of retirement income philosophies is really about retaining risk or transferring it, one might say that the distinction really comes down to a matter of who/what you trust more: the returns provided by the markets, or the guarantees offered by third-party providers (insurance companies, pension plans, government).

If you don’t trust the markets to function effectively and give you reasonable returns in the long run that compensate you for the risk, there’s little value to trying to manage it through various spending strategies. In other words, if you don’t trust the presence of an equity risk premium, it’s better to simply transfer the risk, and makes little sense to retain it. And as research shows, if you don’t trust markets, you probably won’t want to invest in them anyway.

Alternatively, if you do have confidence in the capability of markets to ultimately deliver an equity risk premium in the long run, arguably it makes little sense to transfer the risk when it can be managed through spending strategies while retaining the opportunity to enjoy higher returns and greater wealth in the long run. Especially since in current markets, the spending offered by guarantees (e.g., a lifetime immediate inflation-adjusted annuity) aren’t materially different than those implied by conservative spending strategies (e.g., safe withdrawal rates); both produce lifetime inflation-adjusted spending results in the neighborhood of 3.5% - 4% of the retiree’s initial account balance. Which isn’t entirely surprising, as both individuals and insurance companies are subject to the same capital markets assumptions, and in fact insurance-based strategies shouldn’t produce better results on average or the insurance company itself (and therefore the retiree too) would be at even greater risk of default!

Of course, the caveat remains that “markets” and the economy in the aggregate may not support this spending level in the long run, but ultimately that remains a concern of both risk retention and risk transfer strategies, for the simple reason that again both are subject to the same capital markets and the same exogenous shocks and events. The low-interest-rate environment damaging retirees today is damaging insurance companies as well, and the kinds of Great Depression and World War events that have been destructive to safe withdrawal rates throughout history around the globe have been similarly damaging to insurance companies, corporations, and governments. In other words, while both strategies can be managed in a manner to make the risks very very low, the remaining risks that can’t be “perfectly” eliminated are actually highly correlated across both philosophies!

The bottom line, though, is simply this – the real distinction in retirement income philosophies and strategies is not really about which is “safe” and which is not, as any of the strategies can be managed in a manner that is safe or in a manner that is more risky (and at least has “a probability of failure”). The real distinction is whether (market and longevity) risk is transferred or retained, and if retained how those risks are managed or avoided. For which, given a world of uncertainty, there are no absolute “correct” answers about what the future may hold… which is what makes them a matter of retirement income philosophy in the first place!

Excellent post, Michael! I like the way you reframed the strategies in your graph – and it really is a question about whether one trusts the markets to continue to behave more or less as they have behaved in the past, or if “it’s different this time”…

With Italian financial market data since 1900, the 4% rule has about a 20% success rate / 80% failure rate. So how can we be sure what is the same as what is different from the past?

Our think tank’s focus in getting LDI to translate to retail led us to an idea of using the labels “Probability” and “Prevention.” While watching last year’s Football playoffs, we thought the analogy of a “prevent defense” fit nicely. You’re can’t guaranty against a touchdown, since that’s impossible, but you can employ a distinctly different strategy that’s intended to minimize the risk. And to keep it simple for your player’s realistic limitations, you either empty the prevent defense or you don’t (a binary approach as opposed to six shades of gray on an efficient frontier of defensive formations). So too with longevity risk tolerance, we decided. Anything more complicated than a binary approach to solving for differences in longevity risk tolerance feels impossible to execute against, at least for the average retiree. And hopefully someday it will be much easier to diversify annuitization exposure across multiple issuers, perhaps even in a seamless way along the lines of mutual fund “funds of funds.” That seem likes like positive and natural evolution to us. http://www.openarchitecture2020.com

Sorry for spell check error – should have read “you either employ the prevent defense or you don’t….” – mrc

Thank you, this is a nice view of the matter.

What would have been the success rate in Italy since 1900 for those who chose a “safety first” methodology if we defined “success” the same as we do with the 4% rule, namely as maintaining a consistent inflation adjusted standard of living. I don’t have the data, but suspect it would be closer to 0% than 20%. Why act as if inflation risk were no more significant than market risk or longevity risk?

I don’t think it would have been possible. Inflation-protected assets are a relatively new tool.

So then aren’t we comparing apples and oranges? One technique seeks to protect the retiree from market risk and longevity risk at the cost of greatly exacerbating inflation risk, while the other seeks to protect against inflation risk at the cost of some increase in longevity risk and market risk. Can either be truly said to be less risky?

A few points:

1. We didn’t have inflation-protected fixed income assets in the past, but we have them now.

2. Safety-first is NOT an all-or-nothing type deal except in its most extremist forms. There is still a role for stocks to hedge long-term inflation.

3. Your explanation is actually a good description of why integrating tools from both sides of the spectrum can build a more efficient retirement income plan that better hedges the full range of risks.

Nor am I suggesting that no one should own a TIP or an SPIA, only that the term “Safety First” is highly misleading and the comparison with the 4% rule an “apples and oranges” comparison.

1. I have not yet tried to structure a 30 year ladder of TIPs and rather doubt it would be feasible or even possible, but I highly suspect that if one were to do so, one would end up with an initial payout rate dramatically lower than 4%. An more appropriate comparison, then, would be for the success rate of that portfolio with the success rate for a diversified portfolio using the same initial withdrawal rate. Even a portfolio of TIPs would still have some risk since the risk of a government default must be clearly more than 0% – especially under the kinds of catastrophic circumstances that would lead to the failure of the diversified portfolio with the same starting withdrawal rate. Both are more than zero and almost impossible to calculate, let alone compare in any meaningful way. Of course, that would still leave open the issue of longevity risk and which approach would better protect against that.

2. I am not aware of any insurance company that offers an uncapped inflation protected SPIA, but would love to hear about one, especially if it is available in New York. That would come closer be being a truly “safety first” approach, but, as Michael points out, that would still leave open the issue of “Counter Party” risk which may be incalculable but is ccertainly more than 0%. Moreover, as Michael points out, such a failure would be catastrophic.

Moreover, if such an uncapped SPIA were to exist, I rather suspect that the initial payout would be less than 4% (actually 4.5%, but let’s not get picky). Thus the appropriate comparison would be between the risk of failure of that SPIA (perhaps small, but greater than 0%) and the risk of failure from a diversified portfolio at that initial withdrawal rate.

I rather doubt that either of these comparisons can be made in any meaningful way, but absent that it is simply misleading to say that one technique is unequivocally “safer” than the other. We need to stop misleading our clients with the siren song of “safety”. We don’t live in a risk free world. We never have and are not likely to anytime soon. Rather, we need to help our clients, as you say, to ” build a more efficient retirement income plan that better hedges the full range of risks”.

I’ve got a couple of Advisor Perspectives columns coming out in a couple of weeks. I wish they were out already, because they would fit into this discussion perfectly.

In short order, 30-year TIPS ladders exist, and the current payout rate is 3.65%.

CPI-adjusted SPIAs exist, though only with a few companies. The pricing is not competitive and I wouldn’t suggest using them. For a 65-year old couple with 100% survivor’s payout, the current rate is 3.75%.

As for the 4% rule, my estimate for a person seeking a 90% chance for success with CPI-adjusted spending with a 50% stock allocation over 30 years with 0.5% portfolio management and expenses is: 2.88%. Of course, this strategy also offers upside unavailable with the others. But the cost of that upside is a need to start with a lower rate as downside protection.

These estimates all assume a starting point of low interest rates, so they are no longer apples and oranges comparisons.

Indeed, the first two strategies are not 100% safe. Nothing is. But the conventions of retirement planning such as “safe withdrawal rates” for the 4% rule already suggest that safe does not mean 100% safe. There are modifiers, such as safe in the context of simulated through US history and assuming no fees, or safe subject to the caveat that contractual guarantees may not be met.

I’ll look forward to reading those articles, but we now seem to have returned to Michael’s point of risk transfer vs risk retention.

Even so, I am curious as to three things.

1- If the assumptions you used are the similar to those previously used, namely a reduced risk premium and lower rates, then what do they imply more broadly for he economy, for inflation, for the viability of insurance companies, and indeed, for the prospects of the US government being able to avoid defaulting on at least some of its debt?

2 – Have you done a sensitivity analysis on your modified assumptions for the risk premium?

3 – What would be the impact of a higher stock allocation?

I look forward to your forthcoming articles, but I still suggest that “safety first” is highly misleading. I, for one, fully accept your amendments to the term “safe withdrawal rate” and do, in fact present it to clients in a similar manner. But fair is fair – then “Safety First” should also have similar amendments if we are to avoid misleading clients.

I’m not an insurance agent, but our group has considered SPIAs with COLAs that seem to be more prevalent than CPI-linked products, and perhaps another option to consider in this discussion. Also, a risk that seems worth including in a holistic comparison of apples is what might be termed “health risks” or “behavioral risks.” For example, I’m Personally acquainted with an eighty year old woman who wound up in the emergency room twice in 2010 for stress-related stomach issues due to market volatility. For those not cut out to be successful in the risk-based capital markets (including high duration TIPs), solving with statistical data leaves out the fact that losing years of quality health is sub-optimal.

I have no argument with anything you have said. I do not deny that market risk exists. That would, of course, be absurd. I only object to pretending that it is synonymous with risk and that anything without market risk is “Safe” or “Risk Free” . That is highly misleading.

Perhaps there really are only two certainties in life, and “safety” is a relative term. Now, as for getting the term “risk free rate” out of the financial economics textbooks….

Yes and yes again. In fairness, though, I would hope that when the text books speak of the “risk free rate” they are doing so within the context of Modern Portfolio Theory which, among other things, posits a market rate of return and a risk premium and defines market risk as being limited to volatility. That may not be what our clients are thinking of when they use the term, but at least the textbooks are (I hope) using the term in a more limited context.

David,

Thanks. After lots of internal debate, I decided that for my estimates of withdrawal rates, I would no lower the equity premiums from historical levels. This is for me personally, though I have some other work with co-authors which still does that. There are lots of good arguments why the equity premium might not be less in the future. So my forecasts reflect low interest rates today, which slowly pick up over time. Stock returns are also lower to keep the same risk premium, though they eventually get back up to their historical averages.

With this setup, the higher stock allocation generally helps.

About insurance company viability, the low rates might cause some short-term pain as they adjust, but to the extent that this is why annuity rates are also lower today, it shouldn’t be a major problem.

About safety first, though it’s not 100% certain, it does reflect the idea that first, before we were about investing for upside, we need to make efforts to protect as best as we possibly can the retiree’s basic needs. I’m okay with moving away from the term to some extent, but I think it is still fundamentally acceptable.

Wade,

Please don’t get me wrong. I have no opinion on the future path of the equity risk premium. Nor, for that matter, do I have any opinion on interest rates (other than to note the obvious, that there is a whole lot more room on the upside than the downside, but then again given negative interest rates in Switzerland, even that may not be true). My point was only that these results are heavily assumption dependent and those assumptions may or may not prove accurate. Moreover, it would seem that if we are going to start making assumptions about future trends, it might be worthwhile to try to think through the impact of those assumptions beyond just their impact on our portfolios.

As for the terminology, my concern is that when we start using those kinds of terms our clients tend to actually believe us. That’s where it starts to get scary. I don’t disagree with the approach of focusing on different needs differently, but see the inclusion of equities as less a matter of “investing for upside” than a matter of diversifying risks. I’ll accept a certain amount of market risk to offset other risks.

Of course it may not work, but even TIPS have their own risks. Besides the risk of default (still greater than 0%), outside of a tax qualified account, the OID tax would kill any prospect of their providing any spendable income so they are limited to a tax qualified account. Inside a tax qualified account, they are subject, of course, to the vagaries of Congress over the next umpty ump years which can hardly be characterized as “risk free”.

I have no argument with funding different client needs differently. Indeed, my IPSs tend in that direction. I just think that Michael is right that we need to think and, much more importantly, speak to our clients less in absolute terms of “safe” and “risky” and more in relative and probabilistic terms. After all, they might actually believe us.

Great posting, but with all my love and respect, Michael, you still don’t go far enough. The whole notion of “safety” in this context is highly misleading. One would hope that by the time one is ready to retire, it might have become clear that we just don’t live in a risk free world and the only thing that can be said with any certainty about the future is that it remains unknown and will remain unknown until we get the benefit of hindsight.

Yes, market risk exists, but it is not by any means the only risk out there. As Michael points out, here, insurance companies are no more immune to market risk than the rest of us. They are not super investors, but mediocre investors at best. They can’t reliably do any better with their investments than the rest of us and when they fail they fail catastrophically.

Yes longevity risk exists and this is the one and ONLY place that insurance companies bring anything to the table. Here, annuities can make an important contribution, but it comes at a price and that is ALL that they can do.

And what about inflation risk? The 4% Rule at least offers the prospect of addressing inflation risk, but annuities do not. They may allow for some limited increase in payouts, but I am still waiting to see the annuity that would maintain a retiree’s lifestyle if they have the misfortune to retire in an environment similar to that faced by anyone retiring in 1968. The 4% rule would have.

Let’s stop pretending that the concept of “risk free” when it comes to investing is anything but oxymoron, or worse, a monumental trap for the unwary. Let’s stop deceiving our clients and ourselves and acknowledge that he reality is that we do not now, never have, and are very unlikely to ever live in a risk free world. There are different kinds of risk and our job is to help our clients balance the risks that they take and not to lull them to sleep with false promises of “Risk Free” or “Safe” investment strategies.

Well said Michael! “…the caveat remains that “markets” and the economy in the aggregate may not support this spending level in the long run, but ultimately that remains a concern of both risk retention and risk transfer strategies, for the simple reason that again both are subject to the same capital markets and the same exogenous shocks and events.” Your summary goes right to the Dynamic Updating principle where new data is added and the whole income process revisited each year so that spending may be better measured and managed along the way. Risk is always present – whether one chooses to see it or not (retain it or transfer it). We all live in the same closed system. Again, well said!

I like the concept of the ‘risk transfer’ or ‘risk retention’ perspective.

Perhaps it’s not so much ‘risk retention’ strategies, but rather ‘how much risk’ is retained, versus how much risk is transferred, during different phases of retirement.

Trusting in the ‘equity risk premium’ seems fine for wealth accumulators, given they have longevity with regards to risk and time, but the fact that the equity risk premium can disappear for long periods of time, can be devastating for early retirees.

A set and forget strategy of relying upon equity risk premiums for all stages of retirement I’d suggest papers from Wade Pfau and Michael Drew tend to cover this issue quite well.

Michael, your other papers relating to asset allocation changes in retirement phases document this extremely well. This article appears a more ‘static’ view, but a ‘progressive’ risk retention debate is an interesting perspective.

One thing that you left out of the discussion is that in some cases, it may be possible to increase the level of income paid as an annuity because an annuity provider (i.e., a insurance company, a pension plan, social security) can pool longevity risks among annuitants. This pooling effectively permits the annuity providing entity to reallocate money in the risk pool from those who die earlier than expected to those who live longer than expected. This type of pooling is not available in non-annuitized solutions.

Fred,

I know it’s a bit buried in the middle (there’s a lot to cover!), but I do point out that transferring longevity risk IS an effective risk transfer mechanism. No disagreement here – the ability of annuity companies to pool longevity risk is a genuine and unique benefit.

– Michael

You don’t speak just to planners. I’m just a curious about-to-be-retiree and am grateful to find articulate explorations like yours. In planner client-land it can be hard to find plain talk about overarching or meta-issues like the risk landscape you probe here. Thanks and keep’em coming. I learn from the comments, too.

The psychological factors must show up front and center given the amount of uncertainty and difficulty comparing different strategies; at least, this seems true in my case. I hate to spend good money on something that’s shaky, or purports to be less risky than it really is. I don’t have a grudge against annuities, and probably will buy one at some point, but it will be a hard choice if I feel like some snake oil salesman’s mark. The stock market seems to me better in this respect, if you deal in widely traded issues: lots of other people’s gut check–buried in the stock price–helps to supplement my own. When sizing up an insurance company and its particular offering, by comparison, I feel pretty lonely.

In article after article I read, authors will say things such as “Insurance companies do have failures, thus…” without any further discussion of the outcomes of such failures for the policyholders of these failed companies. In a January 2012 Index Compendium article titled, “FDIC Bested By Annuities On Unprotected Account Balances” the author states “Since inception, all of the annuity owners of failed annuity carriers received their full account value up to the limits of the state guaranty fund…” It seems fair when discussing insurance company failures that we names names of those who left annuity owners without their contractually-protected balance before dismissing a safety-first income approach as equally (or even close to equal) risky as a systematic withdrawal strategy. In fact, utilizing historical data in the calculation of a systematic withdrawal method must allow for the safety-first practitioner to similarly use historical data in their discussions. To assert that insurance companies can fail is absolutely true, yet it quickly and unfairly dismisses the primary benefit of risk transfer to an institution (or three, if using multiple carriers to remain under state guaranty limits) who are A-rated, have survived recessions and depressions, and whose sole business is to fulfill guaranteed promises. With such historical data available, it allows for truer comparisons of the success and failure rates of probability-based strategies with those of contractually guaranteed income strategies.

An assertion is often made that annuity-based strategies fail to keep pace with inflation. This implies that every dollar the client has is placed into the annuity strategy. By utilizing either a flooring (essential vs discretionary) or an age-banded income strategy, assets not required for near-term essential income needs will be free to remain in risk-based investments, to counter the effects of inflation. When built properly, a safety-first, guaranteed income strategy usually requires less money dedicated to income production than a probability-based strategy (less margin is required for seasons with poor market returns) and thus keeps more money available for other retirement risks and opportunities, including inflation. Additionally, your brilliant discussion of the “retirement smile” should cause retirement planners to rethink their inflation assumptions for retirees, while simultaneously giving reason to build some sort of long term care strategy into the income plan, even if a minimal one.

Michael, great discussion.

Michael,

Nice way of describing the choice. Unfortunately, people like to think in binary terms – safe vs. dangerous – when, in fact, the outcomes run a range of possibilities. My clients are always a tad disappointed when I let them know that there isn’t a “right” answer, just better answers for their situation.

Btw, thanks for the term “Risk of Adjustment” for retirement planning. I’ve been using the concept since I started but never had a good name for it. Again, it comes back to breaking down that binary thinking, which, I’ve found, helps clients sleep much better at night.

Thanks Michael. I do think your risk transfer vs. risk retention distinction makes sense.

But I still think that probability-based vs. safety-first is still a fair distinction, and one that’s easier to grasp. It seems a stretch to believe that withdrawals from a volatile portfolio will be just as safe as a contractual guarantee, which is based on an investment portfolio which primarily holds individual bonds to their maturity dates.

A recommendation for an income annuity can really hurt the bottom line of an advisor charging an AUM fee, and I think this causes a lot of advisors to rationalize in their minds an aversion to income annuities which just doesn’t make sense for some of their clients. You can see some of this in other comments here, such as the notion that it’s all-or-nothing for an annuity, or that insurance companies are really bad investors [when they mostly just have a duration-matched bond portfolio designed by actuaries], or the straw-man that “safety-first” means absolute elimination of all possible risk.

Wade,

Withdrawals from a “volatile” portfolio can certainly be as safe or safer than a contractual guarantee. Which would you prefer – withdrawing $1/year from a $1,000,000 portfolio, or giving it to a B-rated insurance company?

The fact that many advisors happen to choose portfolios/withdrawal rates that are high enough to introduce some risk of failure is a function of the decision itself, not the idea that “there’s no withdrawal rate low enough to be safe.” Just as advisors and their clients can choose amongst AAA-rated or B-rated insurance companies, which also have very different probabilities of failure. These are distinctions about the level of risk being chosen, and are relevant in both portfolio-based AND insurance-based solutions; their distinction is not safety vs risk, but who is (primarily) responsible for managing the risk and the associated trade-offs involved.

– Michael

Michael,

Yes, if the withdrawal rate from a volatile portfolio is low enough, then it can certainly become very safe. Your 0.000001% withdrawal rate example should work out fine.

But what about a 4% withdrawal rate? That’s about what you could get now with contractual guarantees using a 20-year TIPS ladder and a DIA. You lose upside potential though. Of course this is not 100% safe, as nothing is. But it’s close.

With a 4% withdrawal rate from a volatile portfolio, you might maximize the probability for success at about 70-80% with today’s low interest rates. With fees (as it is important to remember that the original 4% rule assumes no AUM fee or fund expense ratios), this might be down to more like 60-70%. But there is upside potential. There’s some chance that even an 8% withdrawal rate could work out.

So this distinction does go beyond just risk retention vs. risk transfer. Risk retention vs. risk transfer IS an important part of the story. But so is upside vs. downside. Individual bonds vs. equity premium. I’m still not convinced that probably-based and safety-first are not better all-encompassing terms for this distinction.

Wade,

I don’t disagree that there are a range of withdrawal rate strategies that have a range of probabilistic outcomes. But my point is that there ARE “safety-first” approaches in that framework – it’s just about setting the withdrawal rate “low enough” to be safe. We may debate about exactly WHERE that line is, but there is clearly SOME ‘safety-first’ approach.

Similarly, not all insurance companies are equal, as even rating agencies note. There is clearly SOME probabilistic difference between buying an annuity from a B-rated insurance company, versus an AAA-rated one.

Thus, the point is simply that BOTH sides have probabilistic measures, and BOTH sides can be implemented in a safety-first approach. They are not unique and mutually exclusive categories, and do not describe opposite ends of a spectrum.

Yes, I would agree that there are all sorts of interesting comparisons about when risk-transfer strategies (using insurance) provide better or worse financial outcomes than risk-retention strategies (like safe withdrawal rates), but again that’s my whole point. What we’re comparing is scenarios/environments where retaining and managing the risk can provide better or worse relative outcomes to risk-transfer strategies at any given probabilistic threshold (whether that’s a 70%, 80%, 90%, 99%, or 99.99% probability of success). But any/either/both can be measured probabilistically, and any/either/both can be implemented in a “safety-first” manner. The difference is HOW they’re implemented – by managing the retained risk, or transferring it.

– Michael

Michael,

You are reaching for a counter-example to demonstrate that probabilty vs. safety is artificial. Sure, you could develop a set of strategies with a very low withdrawal rate from a volatile portfolio and an annuity from a very low rated company, and determine that they have the same probability of failure.

But in seeking to break away the value of the contractual guarantee, your distinction also falls apart. You can’t really call it a risk transfer to the insurance company if you aren’t really expecting them to fulfill the obligations.

Maybe a better distinction could be: dedicated income vs. volatile investments? I’m not married to the probability and safety names, but I do think they are more helpful than retention and transfer.

On a slightly separate note, I wonder how confident you are in the arrangement of strategies on your 4-axis chart? For instance, why is VA/GLWB one of only two that is fully on the risk transfer side? With it, you accept a lower payout rate than a SPIA because you are still seeking upside potential, so you are retaining some risk that your standard of living will be lower than it otherwise could have been. In this regard, what does risk even mean for those 4 categories?

And why do safe withdrawal rates have more risk avoidance than variable spending?

Wade,

I will certainly grant that the RANGE of outcomes in the risk-transfer scenarios are generally narrower – a function of how insurance works in general, and how our insurance system is regulated (with various limitations on capital, reserves, investments, and state and Federal backstops). Nonetheless, “safety first” vs “probability-based” still fundamentally evokes a “insurance companies can’t fail and portfolios do” mentality that is merely a function of how they’re COMMONLY used, not natural (nor mutually exclusive) by their definitions. Both can be administered on a safety-first basis (including by changing the portfolio allocation to match an insurance company’s asset-liability-matching strategy), and both can be operated in an ‘unsafe’ manner, none of which is captured by this probability-vs-safety framework.

In terms of the exact arrangement of strategies on the chart as I laid it out, no I’m not at all specifically wedded to the exact placements. To some extent, there were simply space constraints in fitting sometimes-long-worded labels into the graphic, and I’ll grant that some of these strategies have a wide range of uses that itself could vary position on the chart (for instance, a “safe withdrawal rate” at 2% would go upper left, but doing the same “strategy” at a 5% initial rate would be lower left).

It’s also fair to note that this framework is at least muddied by the multiple risks involved – at a minimum, market risk and longevity risk – and some strategies are more effective at transferring, retaining, reducing, or avoiding these risks than others (e.g., risk-transfer works better for longevity risk than market risk, so variable annuity income riders trying to guarantee against both can be a mixed bag position and result).

– Michael

Michael,

Thanks. I think we can have a truce on this now. To me, safety-first isn’t just insurance. It’s also individual bonds held to maturity. But otherwise I don’t have any objections, and can understand your concern that safety-first invokes some sort of inviolabilty for contractual guarantees, which certainly doesn’t exist. In that regard, “safe withdrawal rates” has clearly confused a lot of people too. You’re right, too, that it is tricky to disentangle the longevity and market risk components in these discussions.

Wade,

This itself highlights the issue of “safety” across multiple dimensions, though. I wouldn’t characterize individual bonds held to maturity as “safety-first” necessarily, because it avoids the market risk but doesn’t (necessarily) resolve the longevity risk (unless purchasing a REALLY long bond ladder!).

To say an individual bond ladder retains the longevity risk and avoids the market risk is much more descriptive than just calling it “safety-first”, and also allows it to be more meaningfully distinguished from something like a lifetime immediate annuity (also a “safety-first” approach), which actually avoids the market risk and transfers the longevity risk (to the extent it’s transferred to a credible insurer).

– Michael

Michael,

When considering risk transfer, I also think it is useful to understand how the insurance company is providing the guarantee.

Risks that are specific to you (e.g., you have a family history of longevity), can be easily diversified through the law of large numbers by an insurance company and unless you are highly overfunded for your needs, you almost always want to transfer these risks.

On the other hand risks that are not specific to you (e.g., poor market returns, rocketing up of average life expectancy), are not solved by risk pooling and transferring these risks is really an illusion. So these generally don’t make sense to transfer, since you can perform most of the same risk mitigation strategies that the insurance company can do without having to pay their fee.

This is a wonderful discussion and I thank those who have shared their insights with the rest of us. For myself, I do not consider that “safety first” implies TOTAL safety and is as misleading as David suggests, but the dichotomy Wade uses (“probability based “vs. “safety first”) may invoke, in the mind of a consumer, a distinction between “maybe” and “sure thing”, which will prejudice a reader worried about failure toward the latter. On the other hand, “risk retention” vs “risk transfer” carries its own implication – that each alternative is total (which we know is untrue; one cannot transfer ALL risk with total certainty).

I would also point out that a risk of BOTH alternatives is that a strategy which provides only a small (and presumably acceptable) risk of failure maximizes the “legacy benefit” – the assurance of wealth remaining after the investor’s death. The inevitable cost of that benefit is the income that the investor could have taken during lifetime. Until he’s certain that he’s about to die, the investor cannot “spend down” his account without the risk of running out of money and such a spend down at the last stage of life is unlikely to have the same utility as if taken in early years of retirement (for vacations, etc.).

Another viewpoint is found in Barton Waring’s book “Pension Finance” (Wiley), where he argues that financial economics suggests the beta of the income (funding) source should match the beta of the liability. For individuals in the decumulation phase, we translate his logic in assuming that certain core expenses (food, shelter, healthcare) are necessary to the point of very low variability, and therefore are best matched with an income stream that has a similar profile. We also believe that matching it with a variable income source that is stress-inducing in a behavioral finance context can be sub-optimal for many people who are not cut out for it (volatility-induced reduction of lifespans). Waring takes issue with the use of expected returns from risky assets to fund certain (or risk-free) liabilities, because it leaves you in an unmatched position where risk does not diminish with time: “…risk to portfolio wealth from random and uncertain investment returns does not go away with time, but accumulates….” This is contrary to the way I was taught to think about variability over time in risky assets, which came more from past performance data of financial markets than the core principles in financial economics. If one separates low beta assets and liabilities from higher beta assets and liabilities, and an individual is over-funded for core expenses in a hedged position, they can then employ risk-based assets to fund more discretionary, less necessary expenses (higher beta liabilities). How one hedges a low beta liability with a low beta income stream in Waring’s context becomes a much more simple problem to solve: TIPs, or SPIAs with COLAs, and preferably a diversified portfolio of SPIAs with COLAs to reduce the counterparty risk even more than the state guaranty funds do. Our think tank’s ideas are found at: http://www.openarchitecture2020.com

I have a couple of comments. First, there are state guaranty associations that take over for insurance companies in the event of their failure. They provide amounts of coverage that vary by state, often between $100,000 and $300,000 for annuities. So by purchasing from more than one company in the case of a large annuity purchase, the stream of annuity payments will have an extremely small risk of default associated with them (the entire insurance industry would have to fail for the state guaranty associations to fail, for instance).

Secondly, safety first retirement strategies, I think, become problematic when health care costs are taken into account. Retiree health care costs can vary from very small to well over a million dollars over the course of a retiree couple’s lifetime. It is simply not possible to set aside a fixed amount to cover these costs unless you set aside a great deal of money, and then often most of that money won’t be used for the costs! Monte Carlo testing should therefore be used as a test against any safety first strategies that are devised, and the Monte Carlo testing should incorporate the wide range of health care costs.