Executive Summary

While it is a topic most retirees hope to avoid ever dealing with, the reality is that not all retirement income plans will be successful. Whether due to a retiree’s refusal to plan, reluctance to take the advice of a professional, or simply due to unfortunate circumstances which were outside of a retiree’s control – failures in funding retirement can and do occur. In fact, financial planners routinely do Monte Carlo projections for retirees to determine their prospective probability of failure, especially given growing awareness of sequence of return risk.

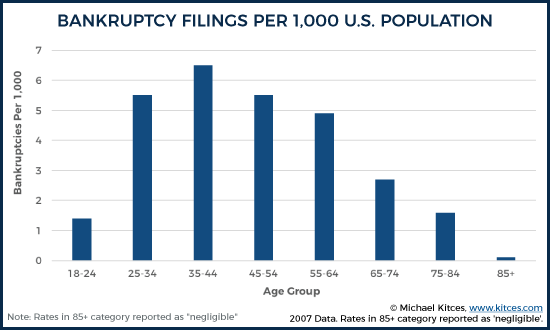

Yet given the reports of low levels of both objective measures of retirement preparedness (such as savings) and subjective measures of retirement preparedness (such as retirement confidence), many financial advisors may be surprised to learn that bankruptcy rates among those over age 65 appears to be less than 3 per 1,000, and actually declines among older retirees. So, what’s going on? If retirees are living longer than ever – which should be making retirement more difficult than ever to afford and sustain, especially given the long-term impact of sequence of return risk – then where are all of the bankrupt retirees?

In this guest post, Derek Tharp – our Research Associate at Kitces.com, and a Ph.D. candidate in the financial planning program at Kansas State University – examines bankruptcy among retirees, finding that the reality is that bankruptcy may not be a great indicator of retirement income planning failure. A retiree who blows through their nest egg doesn’t necessarily end up bankrupt, they simply need to adjust their spending downwards to their new reality. Social Security plus public assistance represent the true consumption “floor” for most. Further, bankruptcy may not even be a great indicator of actual financial strain, as given the rules surrounding bankruptcy, the ways that retirees deplete their retirement assets does not necessarily trigger an actual bankruptcy filing, especially in light of the ways in which bankruptcy laws favor those in retirement.

Nonetheless, the point remains: with longer life expectancies and struggles with retirement preparedness, especially combined with the difficult markets of the past 15 years, the retiree bankruptcy rate is shockingly low. Which suggests that the overwhelming majority of retirees facing retirement shortfalls really are able to downsize their lifestyle to avoid financial ruin when the time comes. Of course, few retirees want to risk even a major lifestyle setback in retirement if they can avoid it. Still, though, if most retirees really are capable of making spending adjustments when necessary… shouldn’t those potential adjustments be better reflected in financial plans in the first place?

Chapter 7 Bankruptcy (For Retirees)

Chapter 7 bankruptcy is the type of bankruptcy most people generally think of when they hear the term “bankruptcy”. Also known as “liquidation” bankruptcy, the Chapter 7 bankruptcy process entails having a debtor’s assets transferred to a bankruptcy estate, where the assets are liquidated to pay to repay creditors, and any remaining (eligible) debts are discharged.

Notably, Chapter 7 doesn’t apply to all forms of debt, and there are some requirements that need to be fulfilled in order to qualify for Chapter 7 in the first place. First, an individual’s income must actually be low enough (at least relative to their debts) that they qualify for Chapter 7 bankruptcy. While the income qualification criteria can get fairly complex, in essence, the income tests assess: (1) whether the individual’s income less than the median in their state; or, (2) if the individual’s income is above the median, whether their disposable income low enough to indicate true financial strain. If either test is met, the individual “passes” and is eligible to file for bankruptcy.

Means testing was introduced in 2005 as a way to combat some abuse of the bankruptcy system – effectively reducing the ability of someone with material income and means to claim bankruptcy (notwithstanding the various bankruptcy exemptions and protections). However, an important caveat to this test—particularly from the perspective of individual’s considering bankruptcy in retirement—is that Social Security income is exempted from one’s income for means testing purposes (effectively making it easier for many retirees to file for bankruptcy).

Beyond these requirements, the debt must actually be dischargeable under Chapter 7. Many common forms of debt, such as credit cards, medical bills, and collections accounts can be discharged. However, other forms of debt or financial obligations, such as student loans, child support, and alimony, generally cannot… which means that someone struggling with those debts would still likely never end up in bankruptcy.

Under Chapter 7 bankruptcy, certain assets are also exempt from liquidation, allowing the debtor to keep those assets while going through bankruptcy. While there is a lot of variation from one state to another, exempt assets include personal property that would be of little value through liquidation (e.g., clothes, household goods, and food) as well as other assets of more substantial value (e.g., wedding rings, vehicles, retirement accounts, and equity in personal residences).

Chapter 13 Bankruptcy

Unlike Chapter 7 bankruptcy, Chapter 13 bankruptcy is a “reorganization” bankruptcy. Chapter 13 does not involve the same liquidation process. Instead, Chapter 13 bankruptcy aims to help debtors come up with plans to get on track and repay (at least some of) their debts.

Chapter 13 bankruptcy is only available to those receiving regular ongoing income. 11 US Code Section 109(e) restricts eligibility for Chapter 13 bankruptcy to only those with less than $394,725 of unsecured debt or less than $1,184,200 of secured debt (thresholds will be updated again in 2019). Debtors are required to participate in credit counseling and development a repayment plan for their debt.

Filing for Chapter 13 generally puts a “freeze” on any current collection efforts, providing some temporary relief while the debtor goes through Chapter 13 proceedings. A trustee is appointed to administer the bankruptcy, and then debtor then makes payments to the trustee, who will then distribute those funds to debtors, according to the repayment plan developed and approved by the court. The debtor is also prohibited from acquiring new forms of debt without permission of the trustee. If a debtor fails to make payments under Chapter 13 bankruptcy, the court may convert the bankruptcy to a Chapter 7 bankruptcy, requiring the liquidation of assets to repay creditors.

The advantage of a Chapter 13 bankruptcy is that an individual may be able to keep their possessions and get back on track, without being compelled to liquidate all of their non-exempt property. Chapter 13 bankruptcy cases generally last from 3-5 years, and, similar to Chapter 7 bankruptcy, some forms of debt can be discharged (i.e., eliminated without actually being fully repaid) upon the completion of the Chapter 13 bankruptcy repayment plan (though obligations such as mortgage debt, child support, alimony, and certain taxes will need to be repaid in full).

Bankruptcy Filing Rates In Retirement

Because bankruptcy filings are a public process (in order to affirm that all debts have been satisfied, bankruptcy involves a public notice process to alert creditors who may have outstanding claims) it is possible to determine the frequency of bankruptcy filings.

The chart above reports bankruptcy filing rates by age group (non-business Chapter 7 plus Chapter 13). Thorne, Warren, and Sullivan (2008) found that in 2007, the bankruptcy rate per thousand U.S. population peaked at the age group of 35-44 with 6.5 per thousand. For individuals between ages 55-64, this rate declined to 4.9; between 75-84 the rate was 1.6 per thousand; and beyond age 85 the rate was so low it was negligible.

This declining rate of bankruptcy in among retirement-aged individuals is notable, because the greatest risk for retirees is outliving their money. Yet with bankruptcy rates decreasing among older adults, the data suggests that bankruptcy in retirement may not be (at least primarily) the result of depleting a portfolio due to longevity or inadequate savings going into retirement!

What Causes Bankruptcy In Retirement?

The fact that bankruptcy filing rates are higher in the early years of retirement and decline in the later years (even as retirement assets would also ostensibly be depleting) raises the question about what actually does trigger bankruptcy in retirement, if not asset depletion.

A 2010 study from Deborah Thorne at the University of Ohio on the interconnected reasons that elder Americans file for bankruptcy found that credit card debt and illness/injury (which can trigger substantial medical expenses, which may subsequently turn into unpayable medical debts) were the two leading causes of bankruptcy among the elderly (based on self-reports from those who had filed for bankruptcy). As Dirk Cotton has pointed out, sequence of return risk does not appear to be a significant contributor to bankruptcy among the elderly, as only 6.7% of filers reported “retirement” as the source of their bankruptcy, and again bankruptcy rates are highest in the early years of retirement—when failures due to sequence of return risk (based on reasonable withdrawal rates) are mostly non-existent.

As Cotton has argued (and Thorne’s study supports), it appears that the predominant cause of bankruptcy in retirement appears to be an unanticipated shock to one’s income or expenses that results in them becoming overextended and not being able to meet their financial obligations. It’s important to note that these shocks are different than someone just living beyond their means, as running a portfolio to $0 doesn’t necessarily trigger any conditions that would even make one eligible for bankruptcy. Depletion might require a material downward adjustment in one’s level of spending, but with no debts outstanding that cannot be paid, there is no actual trigger for bankruptcy.

As indicated in the chart above, bankruptcy actually seems to decline with age. Which, consistent with the Thorne’s (2010) findings, would suggest that financial shocks are a more significant cause of bankruptcy in retirement than depleting portfolios. However, what may remain unclear is why financial shocks would decline with age as well. To address this question, it is helpful to look at who is susceptible to financial shocks in the first place.

Who Is Susceptible To Bankruptcy In Retirement?

A few factors would seem to primarily drive susceptibility to bankruptcy in retirement. The first is financial fragility, which is the degree to which a small shock in a household’s income or expenses could have a big impact on their overall situation. A household’s debt-to-income ratio (monthly debt payments divided by monthly income) is an important indicator of fragility. Another would be the Fed’s financial obligations ratio, which looks at how much income goes towards fixed payments. All else equal, the higher percentage of a household’s current income that is going towards fixed payments, the more susceptible they are to either an income or an expense shock.

Naturally, one important driver of the debt-to-income ratio is the presence of debt in the first place. Even if a household does have to rely on credit to fund an unexpected medical expense, the less debt they currently have, the better positioned they will be to meet this unexpected obligation.

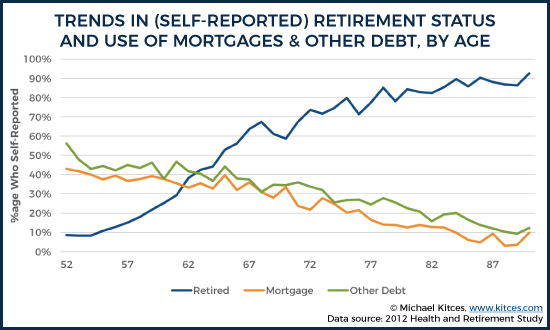

By looking at data from the 2012 Health and Retirement Study (HRS), we can notice a few general trends related to the use of debt amongst individuals at different ages. First, not surprisingly, the percentage of individuals self-reporting themselves as retired increases with age. At age 55, this number is roughly 10%, but it reaches 80% by age 75. But then we can also see that the percentage of people reporting mortgage or other forms of debt also declines with age. At age 55, 37% report having a mortgage and 44% report having other debt. Among those age 70, these numbers decline to 20% and 27%, respectively.

The presence of debt is important because it is a potential source of financial fragility—as debt itself (and an inability to repay it) is the actual trigger of bankruptcy. Debt isn’t always a sign of fragility, as sometimes debt is simply used strategically and there is no material risk of insolvency, but fragility due to debt can be particularly concerning when debt is tied to a retiree’s basic living expenses.

For instance, if a retiree enters retirement with a $1,500 per month mortgage, then they have $18,000 per year earmarked towards a fixed expense (assuming they don’t move or refinance their mortgage, or use a reverse mortgage in retirement to avoid the ongoing payment obligations). It’s these fixed expenses which pose the greatest risk if a retiree experiences an income shock. And then, as Dirk Cotton has noted, things can quickly pile on top of each other and spiral out of control—perhaps as a retiree tries to make things work by taking on credit card debt, pulling equity out of other assets, or turning to high cost lending sources. In other words, while bankruptcy isn’t usually triggered by simply depleting a portfolio, having or taking on a substantial debt – either in response to a financial shock or carrying it into retirement from one’s working years – does increase the likelihood that a retiree will be unable to meet their obligations, and thus need to file for bankruptcy.

However, not all factors which drive susceptibility to bankruptcy actually have anything to do with a household’s overall financial health. For instance, the proportion of exempt to non-exempt assets would be another important factor which influences how likely a retiree may be to file for bankruptcy.

Consider the following example:

Example 1. John is 65 and recently retired. He receives modest Social Security income, has no debt, and his only substantial assets are his $250,000 401(k) and his $150,000 home in a state that offers a 100% homestead exemption. Beyond this, John only owns some personal items and a very modest used car.

Tracy is 65 and recently retired. She receives modest Social Security income, has no debt, and her substantial assets are a $250,000 taxable portfolio (proceeds from the sale of her business) and her $150,000 home in a state that offers only a small homestead exemption. Beyond this, Tracy only owns some personal items and a very modest used car.

While John and Tracy have relatively similar financial situations from a retirement income perspective, their susceptibility to bankruptcy given a financial shock are very different. Because nearly all of John’s assets are exempt assets from a bankruptcy perspective, a bankruptcy may not harm him much at all. Ignoring potential moral considerations regarding the strategic use of bankruptcy, John could choose to have large and unexpected medical expenses discharged through bankruptcy with little to no adverse impact to himself. Further, John may be able to do so regardless of his actual ability to afford the medical expenses, as his ongoing Social Security income, 401(k), and personal residence are all exempt from bankruptcy.

Meanwhile, the same is not true for Tracy. Because nearly all of her assets are non-exempt assets, bankruptcy is of little strategic use to Tracy. If her assets (less a modest homestead exemption) are sufficient to cover the medical expenses, she is better off just paying them. Thus, John’s higher proportion of exempt assets makes him more susceptible to bankruptcy as a retiree, even though his underlying financial situation is fairly similar to Tracy’s.

And this example illustrates why retiree bankruptcy may not always be a great indicator of actual financial strain. Particularly given the ways in which bankruptcy laws favor retirees (e.g., exempting the types of assets retirees most commonly own and excluding Social Security income from means testing), bankruptcy could sometimes even make sense as a wealth-maximizing strategy in retirement.

Portfolio Depletion As A Bankruptcy Trigger Or “Mere” Spending Adjustment?

In the context that most financial advisors discuss bankruptcy with retirees, the primary concern is that spending all of one’s assets will result in “financial ruin” and cause the retiree to go bankrupt. However, as the data shows, this is rarely actually the case.

Instead, spending down most or all of one’s assets merely necessitates a downward adjustment in retirement spending. Some retirees may try and fight this adjustment, turning to credit cards or other sources of debt to unsustainably prop up their standard of living, but this is different than simply running out of assets — it’s the active accumulation of more obligations beyond spending down one’s portfolio!

Of course, to the extent that a portfolio drawdown exhausts reserves which could be otherwise used to absorb a financial shock, depleting a portfolio clearly increases the potential risk of bankruptcy.

Consider another example:

Example 2. Tracy is 65 and recently retired. She receives modest Social Security income, has no debt, and her only substantial assets are her $250,000 taxable portfolio and her $150,000 home in a state that offers only a small homestead exemption. Beyond this, Tracy only owns some personal items and a very modest used car. However, Tracy’s lifestyle does not align with her savings. Tracy recently met with a financial planner who determined that her current spending would require about $50,000 per year in income from her portfolio in order to supplement her Social Security income. Tracy’s financial planner estimates that she will spend down her portfolio after 6 years by taking $50,000 per year in income from her portfolio.

Is Tracy going to face bankruptcy once she spends down her portfolio? Not necessarily.

While she is going to face a tough wake-up call regarding her spending going forward, her lack of debt means she’s not actually in trouble with any creditors. However, what spending down her portfolio does do is eliminate some assets that can be used to alleviate a financial shock, such as an unexpected medical expense, which, if she attempts to pay for with debt, can end up triggering a bankruptcy later.

Notably, if her assets were in a 401(k) or had strong homestead protections, then bankruptcy might be a viable path for Tracy to handle an expense shock such as medical bills. As a result, she may actually be more susceptible to bankruptcy with exempt assets — though bankruptcy would actually be a wealth-enhancing strategy for her, rather than an indicator of financial strain! Of course, if Tracy is on Medicare, then this risk is limited as well, which could be one contributing factor to the explain why bankruptcy rates actually seem to decrease (rather than increase) with age.

Portfolio Depletion: Planning For Spending Adjustments Vs Bankruptcy

The key point to this discussion is that spending down a portfolio may make a retiree more susceptible to bankruptcy, but doesn’t necessarily ensure bankruptcy or total financial ruin (especially with Social Security and Medicare safety nets). In fact, the data shows that despite the natural rising risk of depleting assets as retirees age, the bankruptcy rate actually decreases among older retirees. Which has implications for both retirees, and the financial advisors working with them.

First, the data suggests that retirees are more capable of making adjustments than traditional financial planning models assume. We know a wide swath of people are underprepared going into retirement relative to what most financial planning models would assume they need. Yet, very low rates of bankruptcy indicate that people are somehow managing to get by. Which means models that project probabilities of “failure” really should be viewed more as probabilities of “adjustment” that real-world retirees routinely make.

Still, this does raise some interesting questions. If retirees are more adept at making adjustments than financial planning models given them credit for, then where are retirees cutting their spending? Are traditional models underestimating how much spending naturally declines later in life? Are generational transfers picking up some of the slack (i.e., children pitching in to support their parents in their later years)? What role are social insurance programs playing in protecting households, perhaps even after they have already reached a financially fragile state? Is the safety net of Medicare and Social Security more effective than what most financial planners give it credit to be?

Additionally, the lack of bankrupt retirees raises some questions for how advisors plan and communication with clients. Should we reframe how we talk about Monte Carlo analyses, focusing even more on probability of “adjustment” rather than probability of failure? Do we need tools which better allow financial advisors to model declining spending throughout retirement? Should reducing financial fragility receive more focus as a pre-retirement planning objective? How would planning advice change if the objective was re-framed as managing one’s financial affairs within a financially fragile state, rather than just focusing on avoiding financial ruin in the form of “bankruptcy” (which seems to rarely result, even after a portfolio has been depleted).

The bottom line is that given how rare bankruptcy in retirement actually is, perhaps it’s time to stop planning on how to avoid bankruptcy and “financial ruin” in retirement, and instead plan to manage the risk of future (downward) spending adjustments and to avoid fragility (as it is fragility that results from a depleted portfolio—not bankruptcy).

So what do you think? Why are bankruptcy rates so low among retirees? Should advisors frame retirement failure differently? How do you talk to your clients about failure in retirement? Please share your thoughts in the comments below!

Another excellent article, Derek. With respect to your key question of “do we need tools which better allow financial advisors to model declining spending throughout retirement?” let me just say that financial advisors need look no further for these tools than our free Actuarial Budget Calculators which permit modeling of 1) declining real dollar future spending budgets, 2) decreasing spending budgets upon the first death within the couple and 3) front-loading of certain types of expenses that are not expected to persist throughout the entire period of retirement (such as travel expenses). All of these modeling features may be used to increase current spending budgets without the need to increase investment risk. The Actuarial Budget Calculators (which can be used to provide an additional “data point” to the spending guidance currently being provided to a client) may be found at our website. http://howmuchcaniaffordtospendinretirement.blogspot.com/

Bankruptcy is not a good measure of successful retirement planning.

In reality, many times family members help out when the going gets tough. Does that equal successful planning? How is that impacting overall family well-being? Could it be kicking the can to the next generation? The folks that are solidly retired now were the last generation to have a sizable pension expectation – how will that be impacted in the new DC world? Congratulations on the low bankruptcy rates in retirement seems rushed without other considerations.

My thoughts exactly. They’re kicking bucket down their *kids’* road, as often as not.

To be honest, there are very cases where bankruptcy makes sense for a post 65 year old age group. To begin with, in order declare chapter 13, you have to making more than your state median income. In most cases, retires make less than the median. They can’t file chapter 13. Second lets compare 2 cases. 80 year old making 30K from social security, no other assets, owes 75k in credit cards. Why declare bankruptcy, he is judgement proof. They can sue him only if he goes out and gets a part time job at age 80. On the hand, 30 year old making 30k and owing the same amount 75k, can possibly be sued and get a judgement issued against him and get haunted for years. They can sue him for future earnings. There is also the chance the 30 year old wants to start a family and buy a home in the future, so there is an advantage to declare bankruptcy now and start from fresh.

There is a way to abuse the system for seniors, spend all your non-qualified money first and then borrow as much as you can on your credit cards and declare chapter 7 without touching your 2 million dollar IRA. You could in theory wipe out your debt, but it is unethical and possibly challenged at bankruptcy court.

The issue of fairness and ethics seem to be higher with seniors. It is easier to admit failure at age 25 versus age 75. Most of my senior clients look at bankruptcy as unethical.

The way I see it is that plan failure is akin to insolvency which in turn is a financial concept. Insolvency, like plan failure may or may not lead to bankruptcy which is a legal term/status. The article seems to be conflating the two concepts and thus a disparity between the rates of bankruptcy and the rates of plan failure among retirees should not be necessarily a contradiction.

Statistics show that Americans are getting worse and worse at saving for retirement, and Social Security isn’t keeping up with the cost of living, especially healthcare. I would not be shocked to see at some point within the next few decades a sudden massive spike in retirement-age bankruptcies. I imagine that such an event could be big enough to cause a recession. Anyone else see this as a possibility?

Both the rate of contributions to retirement plans and total retirement plan assets (both as a percent of wages) have increased since the era of traditional pensions; total plan assets are MUCH higher today than in the past. So while some people obviously are falling short (as they were in the past, and as some surely will in the future), the data don’t really support the idea that Americans are saving less for retirement than in the past.

A most disheartening situation is when a person empties out their 401k account to make payments on credit card debt. Under Georgia law, your retirement account is 100 percent protected from your creditors.