Executive Summary

Back in early 2015, the White House directed the Department of Labor to propose and implement a new rule that sought to impose a fiduciary standard on broker-dealers… or as the President’s administration put it, “Wall Street brokers who benefit from backdoor payments or hidden fees and don’t put the best interest of working and middle class families first.” At the time, the Administration argued that “bad incentives and bad advice” meant that consumers were losing upwards of $17 billion per year to their retirement accounts, implying that any compensation that was based on the sale of a financial product was unduly expensive and inherently “bad”, especially when contrasted against (good) “firms who choose instead to put their clients’ interests first [under a fiduciary assets-under-management model].”

But, as is often the case, such black and white distinctions are rarely so cut and dry, as no fee model is completely without some underlying conflict of interest between a business that wants to get paid and the consumer trying to decide if their services are worthwhile. Especially since in practice, the cumulative costs for clients of advisors who charge under the AUM model can add up to far more than even the most expensive, conflict-ridden financial product.

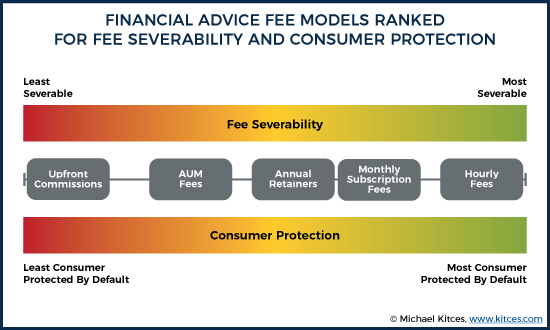

Yet, at the end of the day, while a client who pays a 1% annual fee over the course of seven years on the assets that an advisor manages will end out paying the same amount as someone who pays a 7% upfront commission on an annuity, the reality is that the fee on the annuity is a “sunk cost” (i.e., it’s paid up front to the salesperson and can’t be recovered by the client after the fact), while the client paying 25 basis points every quarter can “fire” the advisor at any time, and simply stop paying the fee if/when they are no longer happy with the level of service they’re getting. Which is why it’s not surprising (and the actual data shows) that advisors under the AUM fee model spend far more time servicing their clients than sales-based brokers. In other words, since the fees under the AUM model are more “severable”, the advisor has a natural incentive to provide more and ongoing service, and the consumer enjoys better protection by being able to terminate the service as soon as it’s not up to snuff.

However, in many cases, there are still hoops that a client has to jump through to sever themselves from the AUM-based advisor, including going through the process of finding a new advisor, opening new accounts, and transferring their money to a new firm. Which can create inertia, and could be one of the contributing factors to the fact that AUM-based advisors have such a high client retention rate (even sometimes in the face of mediocre service)… because in some cases, it’s not that the advisor provides such great service, but simply because leaving is such a pain.

For even more “severable” fee structures, consumers can turn to the newer retainer and subscription fee models. Though perhaps the model with the greatest fee severability is the hourly model, where there are no ongoing or recurring fees and which, by definition, terminates at the end of any meeting where the client doesn’t engage the advisor for any subsequent meetings or service.

All of which leads to the question of whether or not (state-level or Federal) regulators are scrutinizing retainer, subscription, and similar fee-for-service compensation models for advisors (i.e., those models with higher fee severability) properly and, in turn, underappreciate the added consumer protections such models naturally provide. Which, ironically, can end up pushing advisors back towards those models with lower fee severability and less consumer protection, where it’s easier for advisors to charge more and get away with doing less.

Ultimately, the key point is that, if the objective of regulation is to better protect consumers, then it’s important to recognize the role that fee severability plays in the process, as certain types of models (e.g., fee-for-service models which have been gaining traction in recent years) already have more of those key protections naturally built in. And while regulators continue to struggle with finding ways to make the more traditional sales-based models less conflicted and more transparent and severable, perhaps the focus for regulators when looking at the fee-for-service models is simply keeping them that way?

Why Fee Severability Makes AUM Fees Safer Than Commissions

When the Department of Labor (DoL) proposed its fiduciary rule, the White House made the case that conflicted advice compensated by commissions resulted in additional costs to consumer retirement accounts that amounts to at least $17B per year. Accordingly, a key aspect of the Department of Labor’s fiduciary rule was a significant curtailment of commission-based compensation and a regulatory safe harbor that would have nudged the industry heavily towards “Level Fee Fiduciaries” who simply charge an ongoing assets under management (AUM) fee instead of receiving commissions.

Yet, as many DoL fiduciary detractors pointed out, paying ongoing advisory fees can be equal or even more expensive to consumers in the long run. After all, earning a 7% commission for the sale of an annuity that has a seven-year surrender charge ultimately adds up to the same 1%/year AUM fee for an investor that holds for all seven years.

In fact, most annuity carriers just recover their 7% upfront commission by levying a 1%/year additional expense ratio charge (or scrape a 1% interest rate spread) against the annuity contract and charge a surrender fee for whatever portion of the 7% upfront that hadn’t been recovered yet. Thus, when an investor purchases an annuity with a 7% upfront commission and holds it for 3 years, the remaining surrender charge would be 4%... to recover the remaining 4% not yet recovered from the higher expense ratio.

Similarly, when they were popular, B-share mutual funds worked the same way. They often paid out as much as a 5% upfront commission to the selling broker, but then typically charged an expense ratio that was 1% higher than the A-share alternative, and literally had a “CDSC” – Contingent Deferred Sales Charge – which was simply the recovery of the remaining 1%/year annual charges. Thus, again, if an investor bought a B-share mutual fund and sold it after 2 years, there was a 3% CDSC to recover the 3 years of not yet having paid an extra 1%/year.

The key distinction, though, is that while the final commission-based charge on the annuity may be the same 7% after 7 years (or 5% after 5 years for the B share mutual fund) as the 1%/year AUM fee, they’re only the same for the client who stays all 7 years (or 5) years. Which isn’t likely to happen, unless the advisor continues to provide value for all 7 years.

In other words, the commission-based advisor only has to be “good” upfront, at the moment of sale, to earn 7% for the next 7 years. While the fee-based advisor has to be good every year for the next 7 years to earn the same compensation. Which drastically changes the incentives for the advisor in how much time, effort, and resources they put towards servicing their existing clients, versus trying to get the next one.

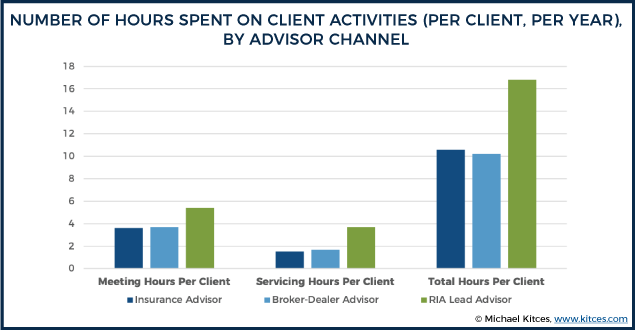

In fact, in our recent Kitces Research study on how advisors spend their time, we found that RIAs under the AUM model spend almost 60% more hours-per-client on direct client activity than more sales-based brokerage advisors, including almost 50% more in meeting-hours-per-client, and more than double the amount of time spend providing client service.

Simply put, even if the costs add up to the same in the long run, ongoing AUM-fee advisors whose fees are more easily “severable” – i.e., the client can terminate the advisor’s ongoing fee as soon as they aren’t satisfied in the advisor’s ongoing value – are more incentivized to provide more and deeper ongoing client service, which is in fact reflected in the research on service time spent per client! Because if those advisors don’t provide the ongoing service to demonstrate ongoing value for their ongoing fee… they get fired! Which effectively makes it “safer” for the consumer (effectively retaining more power in the hands of the consumer to hold the advisor accountable for providing value).

How Fee-For-Service Models Improve Consumer Protection By Increasing Fee Severability

While fees under the AUM model are far more severable than an upfront-paid commission (that typically isn’t refundable at all after the relevant free-look period), it’s notable that the AUM model is not exactly the most severable model.

Not only because many advisory firms bill their AUM fees in advance – which means the client then has to request and obtain a refund of excess fees that were paid but not earned (is a hassle at best) – but also because in many cases, terminating an advisor isn’t just about terminating the advisor’s services, but also creates a necessity to move and repaper the entirety of the client’s investment accounts.

Fortunately (for the consumer), when it comes to many RIAs that use custodians with retail-facing options as well – like Schwab, Fidelity, or TD Ameritrade – it can be as “simple” as just converting an existing account from an advisor-managed to a "retail" account. Though that may still entail not only a call to the advisor to terminate, but additional calls to the custodian to convert the account as well.

For fee-based accounts at many hybrid broker-dealers or other institutions, though, that don’t have a direct-to-consumer retail division, there is no direct path to convert from an advisory to a retail account. And of course, if the whole point is not only for the consumer to terminate their current advisor, but to switch to a new advisor, the AUM model again often necessitates moving and repapering the client’s entire set of investment accounts to the new advisor’s investment platform.

Thus while the AUM model is more fee-severable than a commission-based relationship, it still forces the consumer to not only decide to terminate the advisor, but also to find a new institution or advisor, establish a new relationship, begin the account-opening-and-transfer process there, all to get re-invested in the new account (which even then, may or may not be able to hold all of the securities that were used with the ‘old’ advisor in the old account). All of which creates a lot of additional work for the consumer, increasing the time, stress, and hassle of terminating the advisor, and increasing the temptation of inertia to stay with an only-marginally-valuable advisor… and effectively reducing the fee severability.

Accordingly, it is perhaps unsurprising that not only do “good” advisory firms often have 97%+ retention rates according to traditional advisor benchmarking studies, but a recent PriceMetrix study showed that even “mediocre” advisory firms in the 10th percentile still have an 84% retention rate!

By contrast, advisory firms that charge on an hourly basis have what is arguably the ultimate in fee severability – as the moment the client doesn’t value the services being provided, they simply walk away from the meeting or otherwise end the relationship, and the fee stops! And clients tend to be acutely aware of the fee they’re paying on the hourly model, as the common obligation to write a check at the end of the meeting, and knowing they’re “on the clock”, makes hourly fees highly salient. Which, ironically, can put so much pressure on the hourly model that it’s often difficult to grow it to a sizable client base!

In between the hourly model and the AUM model are various types of retainer or subscription “fee-for-service” models.

Relative to the AUM model, retainer and subscription models have greater fee severability, because they don’t necessarily require the movement of accounts and changing of investments to end the advisory relationship (and fee) and start a new one; they merely require a decision by the client to terminate the advisor and the fee stops.

Still, though, because retainer/subscription models are ongoing “relationship” models – where the default is to remain a client, until the client makes an affirmative decision and action to terminate the relationship – they are still less severable than a pure hourly model, which by default terminates at the end of every meeting (or even after every moment of service), until/unless the client proactively engages the advisor for another meeting or to otherwise continue the service.

In addition, from a practical perspective, not all retainer or subscription fee models are the same, because the less frequent the payments are, the more of a time stretch there is before the client has an opportunity – or at least for the opportunity to become salient – to decide whether to continue renewing the advisor, or terminate them.

Of course, technically, a retainer fee paid in advance can and must still be refunded for the ‘unearned’ portion of the fee – for instance, if an advisor bills quarterly, and the client terminates 1 month into the quarter, the remaining 2 months’ worth of fees must be returned. But in practice, clients aren’t often even reminded of the ongoing fee until they receive an ongoing invoice tied to an ongoing bill. In other words, they may not even recall that they’re dissatisfied with the service until the end of the quarter when the next bill comes, and at that point, it’s likely too late to ask for a refund of the prior now-expired quarter.

Which means the less often the billing frequency, the less severable the service tends to be, while the greater the billing frequency, the more the client is constantly reminded that they’re paying, as well as what they’re paying, and the more frequent the opportunities for the client to make a decision about whether to keep or sever the fee and the advisor’s relationship.

Should Fee Severability Become The Regulatory Focus Of Fee-For-Service Regulation?

From the advisor perspective, fee severability becomes an issue of client retention. The more severable the fee model, the more burden on the advisor to keep adding more value to justify their fees. (Ideally without giving away so much that the firm is no longer profitable!) Especially if the fee is highly salient as well.

From the consumer perspective, fee severability is an issue of consumer protection. The less severable the advisor’s compensation model (all upfront commissions being the logical extreme), the less the consumer has any recourse if they’re not satisfied with the value received and services rendered after the fact. While the more severable the fee model, the easier it is for a consumer to walk away the moment they’re unsatisfied, and the more they’re naturally protected from being “stuck” compensating an advisor for services that weren’t up to snuff (or worse, services not rendered at all).

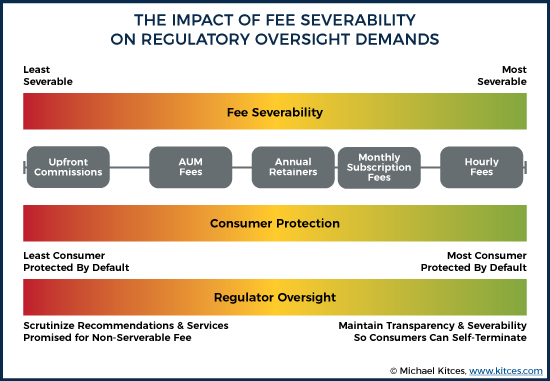

Which means from a regulatory perspective, the less severable the compensation model, the more regulatory scrutiny that’s necessary upfront to ensure consumers are protected (because it’s a “once-and-done” transaction with little recourse after the fact). The more severable the compensation model, the more that natural market forces can operate, where advisors who don’t provide good service simply don’t get or can’t keep the clients to whom they’re not providing value. Because again, the more severable the fee, the less the consumer “needs” the regulator’s scrutiny up front, as the easier it is for the consumer to just walk away all by themselves with little financial risk or consequences beyond paying for the small amount of services already provided.

In turn, then, the implication from the regulatory perspective is that for low-severability models, it’s especially important to establish upfront that the advisor does/will deliver value for the compensation they will receive. While for high-severability models, the most important thing is simply to ensure that they remain high-severability in the first place, to allow market forces to operate.

In practice, this helps to explain why the burden of FINRA regulation (for low-severability commissions) is to determine upfront whether the sale was “suitable” for the client. While conversely, the regulation of RIAs is much more focused on whether the advisor provides ongoing (management or other) services commensurate with the ongoing fee (with relatively less focus on just the upfront recommendation).

Similarly, advisory firms that charge retainer fees (already a relatively highly severable model) are generally limited in collecting fees of no more than $1,200 that are more than six months in advance (per Release No. IA-3060), unless the firm provides an audited balance sheet of the business and additional disclosures. Which is meant to ensure that advisory firms don’t turn an otherwise-highly-severable fee-for-service model into a low-severability version where there’s a risk that the firm might charge a lot up front and then not deliver (or not be around to deliver because it goes out of business) when the time comes. Because again, when it comes to highly severable fee models, one of the most important consumer protections is simply ensuring that it remains easy for the consumer to sever the services.

The significance of the fee severability spectrum from the perspective of current regulation is that it suggests recent state regulatory efforts with respect to the increasingly popular monthly subscription fee model may not be following the most effective track to actually ensure consumer protection.

For instance, several state regulators have increasingly focused on advisors enumerating the exact number of hours they will render services in exchange for their fee, to convert the advisor’s compensation into an hourly-equivalent rate, as a means of determining whether the services are being rendered for a “reasonable” fee (e.g., no more than $150 - $250/hour)… even though ironically, converting the AUM model’s services into an hourly-equivalent fee would reveal a common rate as much as $1,818/hour for investment management on an hours-per-task basis or a “mere” $700/hour including client meeting time as well (given that the average revenue/professional per Investment News’ 2018 benchmarking study is almost $500,000/year, and the average advisor spends only about 5.5 hours/week on investment-related tasks).

In other words, regulators are increasingly scrutinizing what amount of work is being provided for a fee model that is easier for consumers themselves to terminate if the consumer decides the services provided aren’t valuable (or aren’t being provided at all), while ironically not applying the same scrutiny to an AUM model that is actually far harder for consumers to terminate (and thus actually even more in need of scrutiny about whether services are being provided for the fees charged and that there is no “reverse churning” occurring).

Similarly, a number of state regulators have questioned the appropriateness of charging an ongoing monthly fee if the advisor doesn’t necessarily do something or meet with the client every month – effectively discounting the availability of the advisor’s services down to $0. Even though research on the value of a financial advisor – especially AUM advisors helping clients with ongoing portfolios – is the “behavioral alpha” of helping keep clients on board during bear markets. Which may be a huge value… but is only relevant once or twice a decade when the bear market cycle occurs, despite the client paying 40 quarterly AUM fees over the span of a decade for that only-rarely-applicable “service”.

Ultimately, the problem of “mismatched” regulation is that it can unwittingly cause advisory firms to switch away from more consumer-protected models towards ones that have less fee severability. For instance, in the face of recent state regulation, a number of advisory firms have shifted from charging monthly subscription fees, to instead charging an “annual fee, payable monthly” where the consumer receives a committed list of annual (but not monthly) services, and the annual fee is simply ‘financed’ on a monthly basis. Which, ironically, converts a consumer-friendly highly-severable fee model into a less severable commit-to-a-full-year requirement for the consumer!

In other words, when viewed from a fee severability lens of consumer protection, arguably the better regulatory approach is to drive more firms towards fee-for-service models like a monthly subscription model, as it provides the most bite-sized payments that make it easiest for the consumer themselves to quickly terminate, and regulators, in turn, could limit advisors from charging significant upfront fees for a full year of service (per the existing regulations limiting prepayments that are more than $1,200 and more than 6 months in advance), and ensure that consumers can easily terminate the service.

After all, most consumers have had the experience of signing up for a monthly service that was easy to purchase but difficult or impossible to terminate (the proverbial or literal gym membership model), where the key regulatory protection of fee-for-service models is ensuring that consumers can easily terminate the service (ideally by going directly to the payment provider and not even needing to contact the advisor and risk an awkward conversation).

Or stated more simply, encouraging shorter recurring billing periods reduces consumer risk over longer prepayment periods (e.g., annual fees for financial/investment advice, or even AUM fees for quarterly portfolio management). And from there, consumers can simply exercise their power to fire an advisor who isn’t delivering – which they are clearly capable of, given that failure to proactively communicate and engage with clients is already the leading cause of why consumers fire their advisors.

Regulating Fee Saliency And Fee Severability

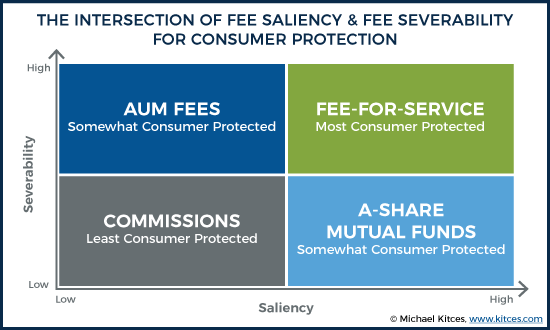

Of course, the other related issue to fee severability is ensuring that consumers know what they’re actually paying in the first place, so that they realize what the cost is, and can make the (ongoing) decision of when or whether to terminate the advisor. In other words, it doesn’t help that the advisor relationship and the advisor’s fees are easily severable if those costs aren’t salient to the consumer in the first place.

Still, though, saliency (and whether costs are transparent enough to be salient) and severability are separate issues. As transparency alone isn’t necessarily sufficient – as a fee that is transparent but too “out of sight, out of mind” isn’t salient enough to be a reminder when necessary. (Which is why RIA regulators typically require advisory firms to provide contemporaneous billing invoices when actually billing their fees – an attempt to make what is otherwise a transparent but not necessarily salient fee more salient). And of course, a fully transparent and highly salient fee that isn’t severable just means the client knows they’re paying too much and receiving too little, but still gives consumers no recourse after the fact (thus requiring an increased level of scrutiny on the associated recommendations when made up front).

Accordingly, the effective regulation of highly-severable models relies on both ensuring that the fees remain severable (e.g., easy for consumers to terminate, no lock-in requirements or mandatory payment periods), and that the fees remain salient (transparent enough for consumers to know what they’re spending, and receiving invoices or other/similar notification as fees occur to ensure they remain top-of-mind so the consumer can evaluate if it’s still worthwhile to continue paying).

From this perspective, the ideal is for all compensation models to progress towards the upper right – being the most salient, and the most severable – which best ensures that consumers are cognizant and aware of what they’re paying, and are able to stop paying when necessary.

Accordingly, regulation of the AUM model often focuses on making the fees more salient (invoices required to be sent to clients) and ensuring they remain severable (unearned fees must be refunded if billed in advance). In contrast, while the load for A-share mutual funds is paid upfront and comes immediately out of the fund’s deposit (so it’s salient), it is not refundable (and therefore not severable). While regulation of commission-based models is increasingly focusing on both upfront compensation disclosures (to make costs more salient) and levelizing compensation (to make costs more severable).

The key point, though, is simply to recognize that fee-for-service models which are already more salient (by virtue of a higher frequency of transparent billing) and more severable (by virtue of having smaller incremental payments that are easier to terminate as soon as the consumer is unsatisfied) already entail the key aspects that tend to drive consumer protection. As contrasted with the traditional trend of the financial services industry itself, which has always been towards models that have less saliency and less severability – naturally more able to lock up clients and charge them higher fees that consumers don’t realize and then can’t terminate anyway.

Which means perhaps the greatest concern about fee-for-service models from the regulatory perspective will simply be ensuring that financial planning costs for consumers remain both salient (with regular invoices provided to consumers) and severable (easily canceled without undue burdens and hoops to jump through) under the fee-for-service model in the first place?

To the extent a “fiduciary” advisor has an ongoing duty to monitor (See, e.g. Tibble v Edison and Reg BI, which only applies the best interest standard at the point of sale); can an advisor with a more “severable” relationship, (i.e. one in which the advisor does not have regular access to the client’s portfolio and behavior surrounding it) truly call him or herself a fiduciary?

ummmmm…. “we found that RIAs under the AUM model spend almost 60% more hours-per-client on direct client activity than more sales-based brokerage advisors, including almost 50% more in meeting-hours-per-client, and more than double the amount of time spend providing client service.”

That’s a lot of Make-Work, unnecessary stuff to justify the fee. No two ways around it.

Given that AUM fees are at least moderately severable, and top RIA performers typically maintain 97% to 98% retention rates (where a material portion of the remaining 2% is due to death), it would seem that clients are valuing at least a big piece of those ongoing services being provided…

Oh I don’t argue that the clients who are paying fees feel they are receiving value.

A. Doesn’t mean they are.

B. the number of those clients is dwindling by the day.

I argue the business is inherently on a suicide mission, more and more advisors trying to find and retain a declining client base.

There’s a big world out there. But not in the AUM model.

And we wonder why we’ll never be taken seriously as an industry… weird, no?

Just had to add, don’t allow tax free distributions from IRAs to pay advisory fees.

That would change EVERYTHING, for the better for the client.

RE: Fee for Value

Admittedly, I lost interest in the article after, once again, running into the 1% advisory fee assumption. I dare say that for “many” AUM advisory platforms, their clients rarely understand the multi-tiered character of the fee schedule and total expenses charged. So, before contemplating the “fee-saliency and fee-severability” spectrum, could we, for once, have a frank discussion about the relationship between fees charged and value delivered? Then there is this.

There are reasons why advisors openly admit to their apprehension of having clients draw a check for their quarterly fees. Now, why is that? — David F. Sterling, Esq., Consultant

David,

You may want to read all the way through the article, since the whole point of “fee saliency” is, literally, making the fees charged more salient (which prompts the discussion between fees charged and value delivered).

The concern you’re raising here is literally the whole point of the fee-saliency issue (from a regulatory/consumer protection perspective), including why cutting fees quarterly by check is more consumer-protected.

– Michael

Michael,

Your point is well taken with this caveat. Though I had lost interest in the article, I did not fail to finish it. I may not have clearly stated my premise that many investors do not investigate nor understand the nature of their fee arrangements with “fee based” advisory firms. Thus, the idea of a knowledgeable and informed client driving the decision to maintain an investor-advisor relationship is suspect.

I understand the inclination to assume that investors are informed and rational. This assumption is a prerequisite for your premise about the consumer protection perspective. That said, I would welcome your thoughts regarding the consumer protective and value delivered elements of AUM fee based business models. I’m quite certain you can provide examples of extreme disparities, which is exactly why I am inclined to commend and promote the “truly” 1% advisory fee presumption. — David