Executive Summary

While there has been ongoing discussion at both the Federal and state levels of how a fiduciary standard should be defined from a legal perspective, and to whom those standards should apply, there has not been much discussion on what it means to be a fiduciary from a moral perspective. Furthermore, this discussion has not addressed the ways in which acknowledging behavioral insights has complicated determining how a fiduciary ought to act, because, it’s actually simpler to determine the ‘best’ advice for a professional to give a client when the only considerations are financial in nature. If financial advisors, as fiduciaries, wish to incorporate behavioral considerations into how they advise clients, determining which course of action to suggest as ‘best’ becomes more complicated.

In this post, Derek Tharp – lead researcher at Kitces.com, and an assistant professor of finance at the University of Southern Maine – discusses his January 2018 Journal of Personal Finance research paper, “The Behaviorally-Enlightened Fiduciary: Addressing Moral Dilemmas Through a Decision-Theoretic Model of Moral Value Judgment”, where he examines whether a fiduciary has a duty to advise clients from a “behaviorally-enlightened” perspective (reaching a conclusion of ‘yes’), and explores some of the underappreciated moral dilemmas that result from advising clients from a behaviorally-informed perspective.

Why would a behaviorally-informed approach lead to an increase in moral dilemmas? Most importantly, advising clients based on something other than objective financial facts necessarily opens the door to acting paternalistically. Should a financial advisor tell a client about an ‘optimal’ solution if they think the mere process of doing so might lead to a worse outcome than just presenting a ‘realistic’ solution? What if they are just trying to nudge clients in the right direction? Where do advisors draw the line, or should they even be worrying about this in the first place?

Nevertheless, there are some circumstances where advisors are perhaps justified in acting paternalistically, but those circumstances are probably fairly rare and advisors should take seriously their duty of disclosure to clients. Specifically, if the potential upside of a non-disclosed strategy to a client is small, the potential down-side to a non-disclosed strategy to a client is large, and a fiduciary is reasonably justified in their beliefs regarding potential outcomes, then a fiduciary may be more likely to be justified in advising a client from a “behaviorally-enlightened” perspective.

Ultimately, the key point is that financial advisors, as fiduciaries, are faced with new moral dilemmas that arise from attempting to incorporate behavioral insights into how they advise clients. While much of the prior focus has been on the legal responsibilities that fiduciaries have to serve their clients, we need to spend time wrestling with moral considerations as well!

In recent years, what it means to be a ‘fiduciary’ from a legal perspective has received a lot of attention – from the DoL Fiduciary Rule to Reg BI, and now individual states that are considering their own fiduciary rules. And while the debate and discussion around public policy are very important, it is also important to consider what it means to be a fiduciary from a moral perspective, as what is legal and what is moral are not necessarily the same.

Of course, as anyone who has taken an ethics class knows, delving into questions of right and wrong is not a straightforward matter. Even trying to agree on foundational questions such as what criteria should be used to judge the morality of an action is difficult, and there are many different ethical schools of thought to which one may subscribe. Utilitarians, deontologists, and virtue ethicists all disagree with one another, and that’s not even including the strong disagreements that exist between factions within these broader schools of thought.

So does that mean we shouldn’t discuss ethical behavior at all? I don’t think so. We probably aren’t going to settle any big philosophical issues, but I think we can still address some trickier ethical questions in a more practical manner and help one another think through how we ought to approach tricky ethical situations that arise with clients. Furthermore, to the extent that ethical principles get codified into professional codes of ethics, we ought to wrestle with certain issues in an open and transparent manner.

In a 2018 paper published in the Journal of Personal Finance (JPF) (preprint available here), I attempt to address one ethical issue I’ve spent quite a bit of time thinking about: How does an advisor, as a fiduciary, advise clients in a behaviorally-informed manner?

How Behavioral Finance Creates Underappreciated Moral Dilemmas

Over the past few decades, there have been many insights offered by behavioral finance research that have influenced advisors’ thinking around working with clients. However, less attention has been given to how acknowledging those insights actually may complicate our understanding of how a fiduciary should advise clients.

In a hypothetical world where financial advisors merely seek to find the “best” financial solutions possible without considering how client behavior might influence the outcomes), determining the ’correct’ advice to give to a client is actually simpler. Of course, when uncertainty is involved, there will always be some room for reasonable professional disagreement, but in a ‘behaviorally-ignorant’ world, a fiduciary would simply look at the financial facts and advise the course (or courses) of action that would result in the best outcome for the client given their financial goals.

However, in the more “behaviorally-enlightened” world that we live in now, a fiduciary can run into some serious dilemmas, because knowing that there are additional behavioral factors to consider will itself make the matter more complicated to consider! For instance, should a fiduciary simply suggest the course of action that provides the best outcome even if they think, from a behavioral perspective, that outcome is highly unlikely to be achieved? Or should the fiduciary discuss an unlikely course of action that would lead to the best outcome (with the caveat that the client may be unlikely to carry that through), and then propose a more behaviorally realistic course of action leading to a suboptimal outcome, because the suboptimal outcome that is more likely to be achieved is still better than the “optimal” recommendation that probably won’t be followed at all?

Furthermore, what if the fiduciary thinks the mere process of disclosing the ideal course of action (ignoring behavioral considerations) will lead to an even worse outcome for the client than just proposing a behaviorally realistic course of action? For example, if an advisor recognizes that simply discussing a complex recommendation leading to an ideal outcome would overwhelm the client to the point that they would no longer be receptive to following any recommendation, even one that is simplified (and, while the outcome may be suboptimal to that of the more complicated recommendation, that would still provide a better outcome from doing nothing at all), should they bring up the more complex recommendation in the first place?

What’s The Ethical Basis For A Fiduciary Duty?

Before diving too far into how this core dilemma might be resolved, it’s helpful to first think about why a fiduciary has any moral duty in the first place. There are several different ethical justifications for a fiduciary duty that have been proposed.

One common school of thought is the ‘contractarian’ explanation, which says fiduciary duties arise purely out of contractual or quasi-contractual obligations. Prior to reaching an actual agreement to engage in a fiduciary relationship, these schools of thought would suggest that no fiduciary relationship can exist, and, as a result, a fiduciary can have no moral duty to a beneficiary. While there is some initial logical appeal to this approach (it may seem odd, for instance, to suggest that a fiduciary duty can arise without any agreement between parties), it’s still not fully convincing that this is the proper ethical justification for a fiduciary duty.

An alternative view (that I personally subscribe to) is that a fiduciary duty is a vulnerability-based moral obligation, as argued by Robert Goodin in his 1985 book, Protecting the Vulnerable, and later elaborated on by Alexei Marcoux in a 2003 article in Business Ethics Quarterly. As discussed in the aforementioned JPF paper:

Goodin argues that while contracts often play a role in formalizing a fiduciary relationship and can explain most of the special responsibilities in such a relationship, the self-assumed obligation justification of fiduciary duty is incomplete in important ways that are not incomplete when explained by the vulnerability model. In support of his argument that fiduciary duties can exist outside of promises or contracts, Goodin treats law as a codification—though, an imperfect one—of moral sentiments within a community. Reliance (i.e., Person A’s justifiable dependence on Person B based on the implicit or explicit actions of Person B) is a particularly important concept for Goodin in making his case that a fiduciary duty can exist even when there is no contract establishing a fiduciary relationship. Consistent with his approach of treating law as a codification of moral sentiments, Goodin cites the doctrine of “estoppel” as an example in both tort and contract law that demonstrates special obligations outside of any contractual agreement.

To quote Goodin (1985, p. 45) specifically:

In law, and presumably morals as well, if you knowingly allow a person to act on the assumption that you are going to do something which you then choose not to do, you are obliged either to disabuse him of that illusion or to do as he expects. Otherwise, you would be liable (legally as well as morally) for any losses he suffered from relying upon erroneous expectations you allowed to persist.

John Stuart Mill expressed similar views in his 1863 book, Utilitarianism (chapter 5):

When a person, either by express promise or conduct, has encouraged another to rely upon his continuing to act in a certain way—to build expectations and calculations, and stake any part of his plan of life upon that supposition—a new series of moral obligations arises on his part towards the person.

So, in short, the idea here is that the contractarian explanation of fiduciary duty is incomplete because it cannot address certain implied moral duties that a fiduciary has even before a fiduciary duty has been formalized by signing a contract to establish the relationship. For further support of this notion (and consistent with Goodin’s views on the codification of moral sentiments via law), we do see that past and current codes of ethics established by organizations such as the FPA, NAPFA, and CFP Board, have all included ethical duties of a financial advisor that presumably occur prior to entering into a formal relationship, particularly related to disclosure.

At first glance, many advisors may intuitively reject the notion that a fiduciary duty can exist prior to entering into an agreement. Couldn’t this suggest that financial planners may not have the discretion to choose the clients with whom they would like to work? Or that third-parties could unilaterally impose a fiduciary duty on a financial planner?

While these questions pose valid concerns, it is possible for a duty to arise prior to entering into an agreement without the objections above being true. The reason being that a fiduciary duty arises only once a planner allows, either implicitly or explicitly, an individual to believe they have become a prospective client of a financial planner. And once this duty arises, it remains in place until an advisor makes explicitly clear that they are no longer open to engaging in a fiduciary duty with a client. This allows for a fiduciary duty to arise before someone has actually signed a contract with an advisor (avoiding an odd carve out for behaving as a fiduciary during the prospecting phase), while still also preserving the autonomy of a professional to choose whom they would (or would not) like to work with.

Behavioral Neutrality and Paternalism

One particular strategy to avoid the complications of advising clients from a behaviorally-enlightened perspective could be to suggest that advisors should just remain behaviorally neutral. If this were possible, this may be a valid argument, but the issue, as noted by Thaler and Sunstein in their book Nudge, is that behavioral neutrality is simply not possible. Even something as basic as choosing the architecture by which we present choices to clients will reflect some sort of values. Because advisors cannot avoid this inherent value preference, we cannot simply suggest that we’re going to remain behaviorally neutral to resolve dilemmas that arise from incorporating behavioral considerations.

In this context, an important topic of consideration is paternalism, which generally involves some form of authoritarian behavior limiting the freedom of another. If we aren’t worried about the influence of choice architecture, framing, and other considerations on our clients’ behavior, then we really wouldn’t have to worry about paternalism. We could just tell them what we think, in pretty much whatever manner we think best to tell them, and the pure facts should be all they need to make a decision. But once we go beyond this perspective and acknowledge that how we advise clients can be as important as what we advise clients, then we’ve opened up the door to making paternalistic decisions for our clients.

To be clear, “paternalism,” here, is used in a manner that is consistent with how Thaler and Sunstein have described “libertarian paternalism” in their book Nudge, which posits that people’s decisions should be influenced “in directions that will improve their lives”, and that “people should be free to do what they like, and to opt out of undesirable arrangements if they want to do so.” This isn’t to imply any stance for or against libertarian paternalism, but just to clarify that we’re not talking about paternalism to the level of any actual use of force against a client (e.g., pinning a client to the ground so they cannot place a trade before market close, cutting their wifi or otherwise tampering with the client’s ability to make a trade they wish to, etc.). Naturally, advisors must carry out lawful requests from their clients, and willful dereliction of their duties to a client would be a violation of their fiduciary duty, so intentionally avoiding a client’s call when an advisor knows they want to ‘panic sell’ would be a violation as well.

Do Fiduciaries Have An Obligation To Advise In A Behaviorally-Enlightened Manner?

The core dilemma here essentially involves the question of whether to present a client with more information, at the risk of overwhelming them to the point of potentially giving up and doing nothing (a potentially worse outcome arising from attempting to be as behaviorally neutral as possible), or to take a more enlightened approach, making assumptions about the simpler and most behaviorally realistic solution for the client to pursue, even though it may not result in the best possible financial outcome.

The following scenario presented in the JPF article provides an example of this dilemma:

Felicia is a financial planner and Chris is her client. In the past, Chris has demonstrated an inability to make financial decisions when presented with multiple options. He dislikes financial topics and becomes overwhelmed trying to evaluate multiple courses of action. Chris has also struggled to follow up with Felicia and get her crucial information in a timely manner. Chris has reached an important milestone and is under a deadline to implement some potential planning items. Felicia believes he has three possible options:

- Strategy A is a complex strategy. It requires careful attention to detail and follow-up from Chris in order to be implemented successfully. It potentially provides the best outcome with successful implementation, but a single mistake would make the outcome worse than Strategy B.

- Strategy B is a simple strategy. It requires no further follow-up from Chris. The outcome is worse than the best-case scenario under Strategy A, but better than implementing Strategy A with an error or simply doing nothing.

- Doing nothing is the worst possible outcome. It is better for Chris to select Strategy A or B regardless of his success in implementation.

Felicia believes she has three feasible communication strategies that she can follow:

- Recommend Strategy A with no mention of Strategy B (OA),

- Recommend Strategy B with no mention of Strategy A (OB),

- Present both Strategies A and B and let Chris decide (OC).

If Felicia recommends Strategy A (OA), she thinks the most likely outcome is that Chris will accept her recommendation, but then make a mistake further on in the implementation stage. If Felicia presents only Strategy B (OB), she thinks Chris will accept her recommendation and execute the simple implementation successfully. If Felicia presents both Strategies A & B (OC), she thinks Chris will become overwhelmed and do nothing.

Based on Felicia’s expectations of the most likely outcomes, her options rank as follows:

OB > OA > OC

As a fiduciary, what should Felicia do in this situation? Should she fulfill her fiduciary duty by recommending the strategy that has the potential to be the best, even though she thinks it is unlikely to be the best in practice? Should she present the outcome she thinks will be the best, even though there is an objectively better option? Or should she present Chris with both options, even though she thinks that will lead to the worst possible outcome?

In other words, Felicia believes that, from a purely financial perspective, the outcome of each option ranks as A > B > C; but when she attempts to incorporate behavioral considerations, the ranking shifts to B > A > C. So, which ranking should she use to guide her actions as a fiduciary?

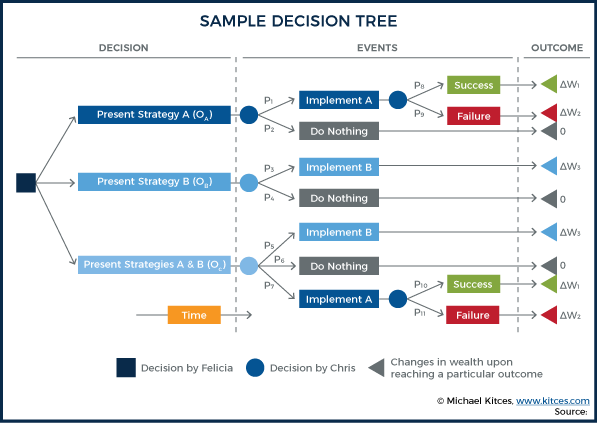

There are a series of arguments made in the paper that ultimately conclude that a fiduciary must advise a client from a behaviorally-enlightened perspective, but that the information provided in the thought experiment above is actually inadequate to resolve the dilemma. A primary reason why the information above is inadequate is that we haven’t addressed relative magnitudes or probabilities of outcomes at all. The thought experiment is set up in terms of better/worse outcomes, but the reality is that how much better (or worse) and how much more likely (or not) outcomes are is also relevant. To consider the various options, consider the following decision tree:

Within this decision tree, probabilities (P1, P2, ... P11) relate to the specific node from which they branch off and each node must equal 100% (e.g., P5 + P6 + P7 = 100%). Using the probabilities associated with a particular path and the change in wealth (ΔW) that results from a particular outcome, the expected value of each of Felicia’s decisions can be determined.

The baseline is assumed to be Chris “doing nothing,” so his change in wealth for each of these paths is zero. Based on the assumptions given in this particular thought experiment, ΔW1, ΔW2, and ΔW3 are all greater than zero.

The decision tree helps us recognize that Felicia can make rational decisions based on hypothetical outcomes that she can derive by considering her estimated probabilities of each decision, as well as the anticipated dollar amount values resulting from each pathway.

Ultimately, I conclude that Felicia has a “prima facie” duty of disclosure, meaning that there should be a strong presumption in favor of disclosure of any ideal course of action in order to preserve Chris’ autonomy, but that disclosure is not an absolute duty, and, under the right circumstances, Felicia could be justified in not disclosing a certain course of action to Chris that may be the best course of action from a purely financial perspective. However, I conclude that in order to override her prima facie duty, the upside of any non-disclosed option must be small, the downside to any non-disclosed option must be large, and Felicia must have sound justifications underlying her beliefs around what is actually in the best interest of her client.

From a practical perspective, I actually doubt there are many scenarios that truly fulfill the requirements identified above. In particular, the scenarios we encounter are likely often not properly balanced with respect to the relative magnitudes of upsides and downsides of non-disclosed options. More commonly, the disparity between potential outcomes would not be sufficiently large enough to warrant Felicia to choose to behave paternalistically with her client. Furthermore, even in the event that disparities were sufficiently large enough to avoid disclosure, it may be difficult for Felicia to fulfill the requirement of having a sound justification for her beliefs of what is truly best for her client.

So, what does this mean from a practical perspective? Ultimately, it means that fiduciary advisors do have a strong presumption in favor of disclosing courses of action that can lead to the best financial outcomes for a client. We may think a client will not carry through a particular course of action, and we may even have good historical reasons to believe that, but that’s often not the type of determination we should be making for a client. First and foremost, we need to let clients make their own decisions.

However, that’s not to say that we can or should ignore behavioral considerations. Certainly, the way we frame things with clients is going to influence their behavior, and we should be cognizant of those influences, and, to the extent possible, transparent about how we do try to help clients through framing.

Additionally, advisors who wish to be more paternalistic with their clients do have some opportunities to be upfront about that wish and request a client’s consent in advance. If Felicia had approached Chris and said, “Chris, throughout our time working together, I want to give you the advice that’s best for your situation, but I also want to take into consideration scenarios that I think may or may not be reasonable for you. If I felt that suggesting a particular course of action may be good in theory but may not a great fit for you in practice, do you mind if I make that assessment and just suggest the course of action that I think will ultimately lead to the best outcome for you?” (You might want to wait using this approach until some trust has been established, or you could run the risk of just sounding sketchy!)

An approach like this is being respectful of Chris’ autonomy, while still opening the door for more paternalistic behavior from Felicia. If Chris is okay with this type of approach, he can consent. If not, then Chris has a chance to state his preference.

Ultimately, the key point is simply to recognize that there are moral dilemmas for fiduciaries that arise in a behaviorally-enlightened world, that are not present in a behaviorally-ignorant world in which advisors don’t have to think about how communication and other considerations influence client behavior. As we learn more about how heuristics and biases influence our decision-making (for both good and bad!), we will inevitably encounter even more dilemmas, so it is important to start considering how fiduciaries should (or should not) incorporate behavioral insights into their advice.

Being a fiduciary is far more important that just expense ratios on investments. Sadly, many miss this. Financial commentators, financial media, and regulators. Candidly, if one is not a practicing financial advisor, let alone providing comprehensive financial planning, not sure that opinion should hold much weight.