Executive Summary

In the early days of the financial advice industry, an advisor’s career track was relatively straightforward. Either they met their insurance policy or investment product sales quota to qualify their contract, or they found some other way to make a living. However, amid the ongoing shift towards the recurring revenue AUM model, and the concomitant rising need for ongoing client advice and servicing, various new roles within firms began to emerge, including client service associates, paraplanners, and (not-responsible-for-business-development) lead advisors.

Along the way, advisory firms generally followed a traditional “performance review” model for determining why and when this new crop of employee advisor roles would progress (or not) on to the next level. Yet in practice, most of corporate America has shifted away from this traditional performance review approach, and towards leadership-based programs to develop and retain talent… while many advisory firms remain mired in the now-outdated management-heavy performance model.

In this guest post, Angie Herbers – Chief Executive and Senior Consultant at Herbers & Company, an independent management and growth consultancy for financial advisory firms – explains why advisory firms still favor the performance model (they’re in the advice business after all, and tend to tell employees what they should be doing instead of providing training, development, and leadership), and how those firms can instead create a stronger culture and ensure that employees are collectively striving towards the same end-goal with a different approach to employee management.

The key distinction is that there is a fine line between telling an employee what they should be doing (and how), and influencing them to go in a direction that helps advance everyone involved. And a first step towards aligning expectations with a more influencing-oriented approach is by developing well-defined career tracks that show (rather than tell) firm employees the path that’s ahead of them… so they know where they’re expected to go (and can see what it takes to get there)!

In the process, though, it’s key to avoid creating a one-size-fits-all, linear path that ignores employees’ strengths and training. Instead, advisory firm owners should recognize at least four baseline career tracks that emerge in a prototypical independent advisory firm. Each track may cater to a particular employee’s strengths and goals, including Financial Planning (for big-picture, strategic thinkers), Advisory (for relationship-driven individuals that like to make things happen), Investment Management (for aspiring CFAs who like research), and Client Services And Operations (for organizers who love to serve others).

Ultimately, implementing a variety of career tracks will provide employees clear paths to travel along as they progress through the firm (and give managers a roadmap they can use to proactively lead their teams rather than reactively telling them how to improve their performance). But first, the leadership team must also have the right mindset, expectations, and plan in place. Once that’s done, and career tracks are established, advisory firms can foster continuous communication and develop talent far more efficiently, by showing them where they can go and letting them step up to the desired challenge and opportunity.

Twenty years ago, the corporate human capital system (i.e., how businesses manage their employees) had a simple method for conducting performance evaluations and awarding raises and promotions.

You paid people what you wanted to pay them, likely had them take a personality assessment before you hired them, and then gave them a performance review quarterly or annually to track what they were doing right or wrong and to develop them within your organization.

This model was made popular by corporate America throughout the 1990’s, and independent advisors followed it, too. In other words, advisory firms made up their human capital programs as they went, based on the trends at the time that were set by what corporate America had done over the preceding decade(s).

Over time, corporate America began to modernize its human capital programs and moved on to leadership-based professional development and training programs. Meanwhile, independent advisors started to lag behind as they persisted in using top-down performance reviews where leaders would give ratings and reviews on past performance behavior in an attempt eliminate future performance issues personality assessments, and other tools to build workforces and “rate” their people.

Why did corporate America shift their programs? Because they began to understand that telling people how to change past behavior quarterly, semi-annual and/or annually created high levels of management. Think about it like this: Do you want performance to improve in the present moment instantly or do you wait to spend the next quarter and/or year side-stepping performance until a performance review? It is much easier for owners, leaders, and managers to ignore performance issues and/or not give deserved performance encouragement and praise when they know a performance review will come in the future.

In this article, we will look at some of the reasons why just talking about performance is not the best way to develop your team. And we are going to show you how to identify what you can implement in your business to create a strong(er) culture and (better) align your employees with what they do best.

The Employee Behavior Problem

Professional services organizations like law firms, accounting firms, and financial advice businesses share a common problem with understanding employee behavior.

The reason these types of companies tend not to understand employee behavior, is that lawyers, accountants, and financial advisors are all paid to give advice. Their daily reality is that giving advice is primarily what they do – and they want to continue giving advice in other interactions as well, even when they are not being paid (or asked) to do so!

What this often means for advisors is that as they build out their teams, they have a tendency to talk to their team members as if they were clients instead of employees. In other words, they give advice instead of training, development, and leadership.

Giving advice when it’s not asked for, however, does not generally lead a person to follow the advice given. Most often, it leads to the opposite reaction – the advice is heard but ignored, and the person receiving the unwanted advice tends to do the exact opposite of what you suggest (or in this case, what said you wanted as their manager!).

Because when someone is given advice and told to do something that they hadn’t asked for feedback on in the first place and/or not open to hearing your advice, human nature tells them that you are trying to control them. And when people feel like someone is attempting to control them, they go into a “fight or flight” mode. They will either fight back, or leave the company, most often fighting back and/or flat out ignoring what you have to tell them.

Often what Herbers & Company sees in professional services firms are employees who are treated like clients, with firm leadership making the assumption that employees want advice on their job performance. Accordingly, many advisory firms turn to performance reviews as a means to help employees improve in their roles. The performance advice given during these reviews, however, don’t always help employees as intended, because advisory firm owners conduct the evaluations with advice-driven conversations to employees who didn’t necessarily ask for (or want) advice in the first place. And when given unwanted advice, employees tend to resist the control they feel is being exerted on their own careers.

Here’s one example of this in practice.

Let’s say you have a young associate advisor whose job is to build financial plans. Naturally, they start out without much training or knowledge. After one particular meeting where they present the plan alongside a lead advisor, the lead advisor pulls them aside afterward to talk about it.

The advisor starts the conversation off on the wrong foot by saying, “Here is what you need to improve and do differently, and here is how I would have done that instead.”

While perhaps intended in a constructive manner, this type of advice session doesn’t produce the intended effect of changing behavior. Instead, it likely made the associate advisor try harder to forge their own path and create their own methods and processes to prove they were a worthy advisor. Because they weren’t ready to hear the advice; all they heard was unsolicited criticism that they didn’t measure up and, as we have seen many times with our clients, the associate advisor would get defensive.

In a case like this, if you want to change behavior and performance, the conversation must change. Instead of saying, “Here’s what I would do,” the conversation needs to begin with a question: “Would you be interested in hearing some of my thoughts for how to improve the presentation of your financial plan?”

Even better, you would hope the associate advisor takes the initiative to ask for feedback. But if they are not asking for it upfront, and you believe they need it, a leader begins the conversation with a question. In this case, you would change the way you approached those who you are leading to help them be more open to receiving what you want to tell them.

The difference in the two examples is the difference between the leader telling and asking—it’s a fine line, but it makes a difference in almost all situations in which behavior and performance are being discussed. If you ask a person if they want advice about their performance, they are more open to receiving it, implementing it, and changing their own behavior given the feedback.

As independent advisors continue to get larger with more employees there is a much-needed change in how they talk to employees about performance. Much like corporate America began to shift away from outdated performance methods, independent advisors must do the same. One 2014 study by Deloitte found as many as 70% of multinational companies who participated in the survey were reconsidering their stance about how they talk about employee performance.

Today, many leaders of advisory firms are beginning to understand that performance feedback is more dangerous than beneficial to organizational growth and company culture, if done wrong. The example of the associate advisor and lead advisor is just a small snapshot of how easy it can be to unknowingly create a damaged culture.

What Is Broken In Employee Performance?

Performance reviews are flawed at their core because they rate people on a scale of right/wrong and good/bad. Who do you know that enjoys being ranked on a scale of how good or bad they are? Unless they’re getting 10/10 marks every time, which is likely no one. And, even perfect scores communicate that nothing needs to be improved. Yet as we know, there is always room for improvement. Which means the employee in a performance review is either given no feedback about where to improve because “nothing is wrong”… or they’re just outright told they’re doing something wrong.

Yet when we start a conversation framed around what someone is doing wrong, the truth is that everything that follows in that conversation will be dysfunctional. The following are four key factors that performance reviews negatively affect, ultimately causing the organization to grow weaker.

- Employee Belief. Human beings do not like to be told they are inadequate. When that happens, their emotional state gets damaged, and their belief in their ability to do great work becomes diminished.

- Company Culture. Performance reviews can easily create a culture where employees see themselves in competition with each other to see who performs better. Instead of acting as a collaborative team, your reviews can pit employees against each other, and employees against leadership creating internal employee/employee/leadership conflict. It’s a no-win situation.

- Management Effectiveness. Reviews are subjective; if a person is rated by three different people, they may all give varying opinions on that person based on likability. If you like and connect with one person over another, the effectiveness of a review can be slanted. Furthermore, performance reviews open the door for a superior to give someone bad scores simply because they don’t like them. Even worse, subjectivity can hide and empower discrimination, as anyone can potentially be downgraded because of the color of their skin, gender, sexual orientation, or other characteristics in a performance review based on biases. It’s a fact that we have seen play out time and again in the news.

- Compensation Tables. Reviews are often used for compensation raises, but again this is an inherently flawed approach. On the surface, reviews may make compensation seem simple; If you do X, you get Y. But, the truth is much more complex. A company that isn’t performing and driving the necessary revenue growth can’t give raises, even if its employees are doing the work to deserve them. And when that disconnect occurs, managers may consciously (or subconsciously) rate employees lower to justify not giving them a raise. On the employee side of the table, greed and disappointment can both grow unchecked when reviews are the sole basis of their compensation. Achieving a high mark from a manager becomes all that matters.

The System is the Problem—and the Solution

These performance review factors that weaken organizations make it easy to see why 95% of managers and 90% of HR professionals think performance reviews are ineffective in driving higher-performing employees. When the numbers so overwhelmingly indicate that the current method is a problem, then we must begin looking elsewhere for a solution.

Because it’s crucial to recognize that the reason why you don’t get desired behaviors from an employee often has more to do with the system in which the person is placed, than with the person themselves. This is a general truth.

So, what kind of system can we create for people that will give them a better construct to grow and flourish with an independent advisory firm? The solution is simple. Every advisory firm needs well-defined career development tracks, to keep everyone on track.

The Solution to Performance Reviews: Defined Career Tracks

By nature, leaders influence. But when leaders give in to their desire for control, they create misaligned expectations within a business and its people suffer. Leadership needs to be about influencing people to go in the direction that you and they both agree is best for all parties involved, without hurting people or bringing them down in the process.

Performance reviews have a tendency to bring people down while pointing those being reviewed in the leader’s chosen direction. To overcome these types of struggles, a firm needs a system that aligns expectations, and creates controlled autonomy for each individual.

Defined career tracks within an advisory firm show employees the path ahead of them so that they know where they are going, and where you want them to go. If they want to choose a different career path within the firm, then the leadership can be supportive of them, and/or together decide if they need to graduate to another firm.

Career tracks don’t tell employees what to do, but they do clearly show them what to do if they want to continue advancing and progressing within a company down a particular path. You may have heard the term “career track” before, but the way I’m going to explain it is likely radically different than how you may have thought about a career track in the past.

Most firms run into a problem with career tracks because they try to smash all possible trajectories into a single track. In other words, every person follows the same system.

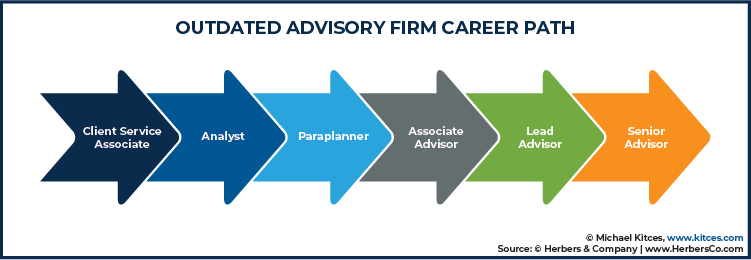

The reality is that different skill sets sit within different people; no one is the same. Not everyone in your firm wants or needs to end up at the same endpoint. The traditional (and outdated) “career path” for a person in an advisory firm for years looked something like this: client service associate, analyst, paraplanner, associate advisor, lead advisor, senior advisor.

But when a career track looks like that, one person advances through wildly different jobs. The idea that they can do them all equally well is largely fantasy, and it does not take into account the different skills of different people.

As one example of this, let’s consider new graduates from CFP programs that get hired as client services associates, which is often where those individuals will enter an advisory firm. Those graduates have been trained for the last four years to do one thing: Give advice. (I know this because over the past two decades I graduated from a CFP program, have taught the classes, contributed to the textbooks, served as faculty, and consulted firms.) When they get slotted into an entry-level client services position, they spend their day scheduling meetings and doing everything except give advice.

The financial services industry does the equivalent of taking someone who was trained to be a doctor and forcing them to be a nurse first. Nurses are necessary, of course, but the people who need to fill those roles are the ones trained to be nurses, and doctors who train to be doctors work as doctors, not nurses.

Think about what the performance reviews will be like for a client services associate who spent the last few years learning to provide advice. A review doesn’t judge them on what they’ve been training to do, simply because the system they’ve been put in isn’t built to help them be successful in that path in the first place.

If someone trained to give advice gets put into a position where they are asked to use skills they haven’t developed, the person is not the problem when their performance suffers. The system is the problem.

It’s here that we need to acknowledge that every firm is different, and so each firm’s career tracks may look different as well. However, every person is also different, and needs different options to choose from based on not just where they want to go, but also based on where they want and have the skills to start.

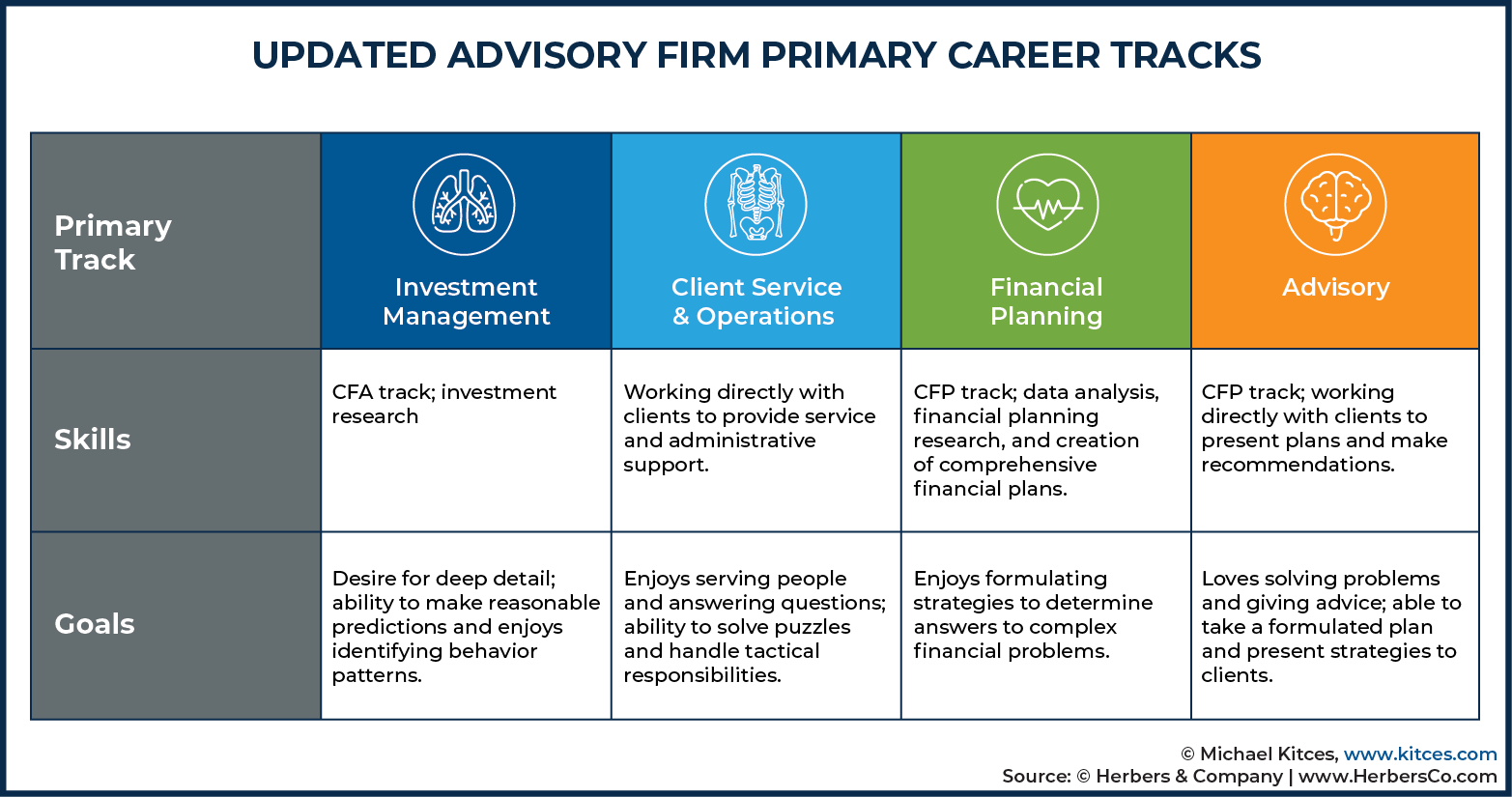

With that, we do need to start at a baseline, which can be framed through four primary career tracks in an independent advisory firm:

- Financial planning

- Advisory

- Investment Management

- Client Services and Operations

In the next section, we’ll look at each track in detail.

How to Create Baseline Career Tracks in Your Advisory Firm

Creating career tracks requires that you understand the skills needed for each track, and understand the goals that a person brings when they decide to pursue that particular track. A good career track outlines the skills needed at each level to advance in your firm depending on the four areas of specialty; financial planning, advisory, investment management and client service and operations. A good way to think about a career track is to create a syllabus, much like how you worked through developing your skills in college, creating a sets of skills and goals for Level, 1, 2, 3, 4, etc.

Let’s look at the goals and skills needed for all four of the primary tracks common to each independent firm.

Investment Management

Skills: This is a CFA track, not a CFP track. It requires a professional with deep (investment) research skills. The best ones tend to understand human behavior as well, because they know how it moves the market.

Goals: Individuals in this track possess a desire to go very deep into detail. They know how to give information to reasonably predict what might happen, and they derive satisfaction from putting behavior patterns together to that end.

Client Service and Operations

Skills: In general, these individuals love to serve people and to work directly with clients. They have great organizational skills, are good at doing the little things with a high level of attention to detail, and are able to work systematically and accurately.

Goals: Their goal is to make clients happy by answering their questions and providing answers. The best ones can assemble puzzles quickly, but they have no idea how to create the picture on the puzzle because they are not strategic. Their job is largely around complete tactical responsibilities.

Financial Planning

Skills: As convenient as it may be to use this example, you can think of these people like Michael Kitces. They have a deep understanding of financial planning principles, and are able to apply them in creating a comprehensive financial plan from client data. They are happy to remain behind the scenes and don’t necessarily want to be client facing, and are constantly seeking new information on everything from financial planning to the laws and regulations, because they want to know what is changing. They’re on the CFP track, and not the CFA track.

Goals: They enjoy using complicated strategies to determine answers to financial problems, and ultimately may look to be movers of change (where their strategies improve the advice across the entire firm, rather than for any one client in particular).

Advisory

Skills: These individuals are what you might refer to as “people person” employees. They can establish strong relationships with clients, while delivering advice and giving recommendations. Like financial planners, advisors are on the CFP track, not the CFA track.

Goals: Advisors love to solve problems and give advice, especially when they’re sitting across from clients, and they would be happy doing this all day long. They are fed information from the planning department, and like to create strategies about how to make things happen by taking that information and turning it into advice to present to their clients.

While each career track is unique and separate, they also all work together to create a high-functioning organization full of individuals able to focus on their skills and play to their strengths.

Think of your firm this way – the advisors who give advice are the heart, the financial planning department is the head, and the investment management team is the lungs. Keeping everything together and running smoothly—the muscles and skeleton—is the client service and operations teams essential for everything else to happen.

Getting Started with Career Tracks As A Replacement For Performance Reviews

Before you implement and develop career tracks, it’s important to take stock of your firm and your attitude. It is no small task to implement career tracks. You need to know that you have the right mindset, expectations, and leadership plan before you begin.

Mindset That Identifies And Solves For System Problems – Not People Problems

You need to look at your business as a system problem, not a people problem. In other words, if you continue to think people are the problem then you are constantly going to have problems because well … of course you know you cannot fix and control people, right? The only thing you can really control is the system you create and deploy for people to follow.

At Herbers & Company we explain to our clients that career tracks are building sidewalks for people to travel down, not asking someone to go blindly into a field where you must run around trying to keep people walking straight. How long do you think people are going to stand in a straight line for you with no sidewalk? Trust me; it is a management heartache.

When you don’t provide the path, people will create their own paths (killing your grass), and they go wherever they want to go, not where you go together. As the leader in your firm, making the transition to a career track system begins internally with you. You need to first be fully supportive of the move to the new system, which means you’re responsible for building that sidewalk.

Alignment of Expectations

Clear career tracks are the system that make those ‘sidewalks’ known to your employees.

Setting your own expectations for how career tracks will transform your firm is important here. For the best results as you transition to career tracks, scale down the scope of expectations you have of others in your firm.

Here’s how simple it can be. If your only expectation for someone in client service is to “be kind”, then you are wide open to training and developing them without needing to control them. Interestingly, your employees will also perform better when your expectations are scaled back – you are not lowering your expectations for a high-quality work product, just reducing the scope of how the role is defined.

We studied this phenomenon at Herbers & Co. in 2008-2010 (we call it the P4 system) and found that when an advisor had high expectations of a new hire, they projected those expectations onto them. But instead of performance increasing, it almost always decreased.

Why would performance decrease when expectations are high? Because bringing in a ‘star’ and expecting them to perform immediately is unrealistic. You set them up to fail right from the start.

Leadership Plan To Replace Performance Reviews with Career Tracks

Businesses use performance reviews because they want to lock themselves into a single point in time where they give employees feedback on performance. So, what would happen if you didn’t have a planned time for feedback? Would the communication within your firm go silent, or would the feedback loop evolve to something that happened constantly?

If you think about human behavior, we want to be in communication and relationships with each other. Eliminating the timed performance reviews creates a desire to communicate on a more frequent basis, opening a feedback loop that evolves people faster through a career track.

With career tracks, there is no set performance review scheduled. Instead, employees will begin to ask for help from those around them, and they learn and grow together. Eliminating performance reviews is the final step of the career track system. After you’ve implemented your tracks, begin practicing the constant feedback loop while you continue to give performance reviews for one or two more quarters, and have a plan in place for when to drop them completely.

The way you shape your business career tracks is up to you and it is often unique to every firm. I do know this to be true, however, that as a leader, if you give a person a path to walk down, they will walk down it. And if you take the time to evaluate where a person is on the track, make efforts to help them grow down a track further, and listen to their feedback, both you and your employees will gain performance.

As while the major issue behind performance problems generally stems from a faulty system of broken sidewalks, the problem generally is not caused by incompetent employees with poor performance!