Executive Summary

When a financial advisor starts their own firm, they face many important choices. One of the key decisions is determining the type of clients they want to serve. Some advisors may choose to take a generalist approach that leaves the door open to working with the broadest possible pool of prospective clients. But with hundreds of thousands of financial advisors competing for the same prospects, it can be challenging to build a generalist advisory business from scratch. Alternatively, many advisors select a client niche to serve and specialize in these individuals’ specific needs, which not only helps clients feel understood but also helps the advisor improve the efficiency of their practice.

In this guest post, Ryan Townsley, founder of Town Capital, an independent RIA, explains how he made the transition from nuclear power plant employee to financial advisor and the process he went through starting out as a generalist who transitioned into a niche where he now works with clients from his former profession.

When Ryan first opened his firm after 15 years in the nuclear power industry, and only a few months working as an advisor, he marketed himself to the broadest range of potential clients possible, using generic marketing and content creation. But after experiencing tepid business growth, he soon realized that he did not stand out in the sea of generalist advisors. So he decided to pivot and serve a niche with which he had significant experience: the nuclear power industry. As a former nuclear engineer, Ryan’s access to specialized knowledge – from understanding how workers in the industry think, to the challenges of their careers, and the financial considerations that come with employment in the industry – helped him decide that this was a niche market he could serve very well.

Ryan’s first step was to redesign his website. He replaced his generic graphics with themes that would be relevant to nuclear power plant employees and made it clear that he would be the go-to planner for those in the industry. His next step was to systematize his planning process to help him work more efficiently as a solo firm owner. And because nuclear power is a process-driven industry, the use of standard workflows was familiar ground for many of his prospective clients. He also built redundancies into his planning process (e.g., using two different risk tolerance assessments), which resonated with his target clients accustomed to built-in redundancies as a key part of operating nuclear power plants. Finally, Ryan created a private Facebook group exclusively for nuclear power workers, where he posts webinars that demonstrate his expertise in addressing the group members’ specific financial needs. And while many members view the free content for their own educational purposes, nearly 20% of the group’s members have become clients!

Ultimately, the key point is that serving a niche has allowed Ryan to build a growing solo practice that allows him to have a solid work-life balance. His experience demonstrates the benefits of using specialized knowledge to create a planning experience that resonates with a firm owner’s target market and creates a more efficient and enjoyable practice!

At one time in the not-so-distant past, I worked as a supervisor in the control room of a nuclear power plant. Yes, kind of like Homer Simpson. It was a career that was interesting, challenging, and rewarding, but I just wasn’t passionate about it. I left that career to pursue my passion for financial planning for many reasons: freedom, a better work schedule, wanting to build something from the ground up, and most importantly to me, a strong desire to make a positive impact in people’s lives.

While working in nuclear power, I was helping people at work unofficially with their finances anyway, kind of the go-to person for finance questions. I had read countless books on investing, money management, and wealth building. I was no expert, but knew more than the average person. At 2 o’clock in the morning at a nuclear plant, when you are doing your best to stay awake, the remedy is often conversations involving fun things like retirement plans and vacation homes. I really enjoyed them.

One day a coworker recommended I make a career out of it because he said I looked happy when I was helping colleagues with their finances and building wealth. So, I did. I started my path to becoming a financial planner. I went to Edward Jones for a short amount of time (a few months), but quickly realized it wasn’t for me. Even though they specialized in career-changing advisers, the methods we were taught for building a business just didn’t resonate with me. I decided to start my own firm. At the time, I had only a few months of finance experience, no clients, no business experience, and plenty of bills to pay. In hindsight, it was crazy.

Nerd Note:

For those who want more perspective (especially if you’re a prospective career changer pursuing a similar path!), I shared my journey in depth on the Financial Advisor Success podcast Episode 285: Fast-Tracking Growth As A Career Changer With A High-Touch Service To Your Prior Profession with Ryan Townsley.

I am an analytical person. My undergraduate degree is in Nuclear Engineering Technology, and I have worked in nuclear power generation for both the military and commercial companies. I spent over 15 years mastering the complicated concepts of nuclear power generation, like thermal dynamics and reactor physics. I attained a Senior Reactor Operator License from the US Nuclear Regulatory Commission to supervise and operate a reactor, the highest level of licensing in the profession. To me, thus far in life, every problem could be solved with math and science.

Looking at the transition to financial advisor more like a scientist than an entrepreneur, I saw it as an equation with many variables. People succeed as financial advisors and in business for many reasons, but those reasons should be repeatable, like the scientific method. I compared it to the Neutron Life Cycle, a formula for reactor physics that describes the exact process a neutron follows in the core. Being successful as an adviser was a process, and every process has a formula. After breaking it down, here was my initial take on success as an adviser:

Success = knowledge + work ethic + decision making + emotional intelligence + business acumen + marketing skills

Seems straightforward. Not simple, but doable. Or so I thought.

Much like in the scientific world, my real-life experiment did not progress exactly as my formula had predicted. In nuclear power, the reactor, the turbine, the generator, and pretty much every other piece of equipment, behave as you would expect with only minor deviations. This is due to years of operation, observation, learning, and adjusting formulas and processes to fit the real world. The early days of nuclear technology, like new scientific discoveries, did not have that level of operating experience. There are too many unknown variables; scientists adapt their formulas and equations to account for the real world as time progresses.

It turns out the same is true for starting a financial planning firm; there are so many more variables and decisions that had to be made along the way than I expected. What software to use? What to name the firm? Fee structures? How do financial advisors even do marketing (like I really have no clue)? Who is my target audience?

This was harder than I thought. My original formula was missing some key factors, especially the most important: who is my ideal client?

To Niche Or Not To Niche At Launch

As I look back, my biggest struggle came with the decision of whether to choose a particular niche or target audience, or not. As I sit here and reflect on this decision, I am so glad I chose the route I did. But it was not a clear decision back then.

Like many prospective advisors transitioning into financial planning from another industry, I was leaving a career I was good at, with stability, job security, and medical benefits, to take a huge risk. I had a 10-year-old daughter, a wife of 15 years, a mortgage, private school tuition, etc. Who am I to say I am only going to work with a particular group of people, when I literally have zero clients? Am I really going to turn away a client who can help pay the bills just because they don’t fit the mold? In my mind, that sounded arrogant. In hindsight, I think it was arrogant to think I could serve the entire world.

My original decision was to open the firm to anyone. I had no target market, and I kept everything vanilla and generic so I wouldn’t offend or discourage anyone who might potentially reach out. Similarly, I used a very generic marketing and content creation service, kept my reach to my local area, and created probably the most boring and non-specific website in the history of advisers.

The website had a sailboat on it (because that’s what retirees like?), and the skyline of New York City in the background (because that seems very finance-industry-professional?). Even though I don’t like boats (I spent enough time on them when I was in the Navy) and I do not live in NYC. I am just outside of Baltimore. It made absolutely no sense.

I trudged along for months with this bland brand that was supposed to help me get as many prospects as possible by being open to absolutely everyone… wondering why no one cared. “I know I genuinely care about people and do a good job; why doesn’t anyone else recognize that?!” Some people came in and out of my process, and I had some very small wins, but I was not on pace to make it worth quitting my career of 15 years. Stress was setting in. I was beginning to think I messed up big time. I could split atoms and make energy, but couldn’t figure out why my new advice business wasn’t working?

I thought that perhaps I wasn’t trying hard enough, so I went back to the drawing board. Back to the math. And here is what I concluded.

Too Little Growth: Back To The Drawing Board

Assumption: As a solopreneur, I could probably serve about 100 clients max if I set up very efficient and streamlined processes.

If I tried to serve the entire United States, I could only serve 0.00004% of the population, assuming any adult was a potential. That would be impossible, and there is absolutely nothing special about me or my firm that would make anyone care. I had been in the industry for less than a year. I had no experience. I wasn’t with a recognizable firm and I did not have a great team of people whom I could lean on for help.

In retrospect, if I were a client, I wouldn’t have hired me either. There was nothing distinguishing me from any of the other nearly 300,000 financial advisors and their websites that a potential client might choose from.

So then I thought: maybe I’ll become a great local adviser. My wife and I had become a part of the community, helping with events, charity, school functions, etc. It made sense. If I tried to serve just my local county, I could serve 0.05% of them. That’s better than the entire country.

However, everyone in the community knew me as “the nuclear guy.” Changing careers at my age may appear reckless. Also, I live in a place with very old money (from which I definitely do not come). There were deep-rooted firms servicing this old money all over the place. Families had been doing business with these firms for generations. I didn’t stand a chance in my local market. Why even try to compete with that?

What if I just looked to help those in STEM careers? No, there are about 10 million people working in a STEM career in the US, according to the Bureau of Labor and Statistics. Still too broad. How about just energy? 7.8 million people in the US work in some capacity of energy, according to this report. Way too many. Plus, I don’t know any of the terminologies that an oil rig worker or a transmission line repair person uses. Energy was still too wide of a net. I needed quality prospects, not quantity.

That’s when I realized that I was doing it wrong from day one. I needed to relate this problem to a process I understood to fully embrace the solution. During the nuclear fission process (when an atom is split), neutrons are released along with various other isotopes. Most fissions will release multiple neutrons, and they can go on to cause fission as well, which is what makes nuclear fission a chain reaction. Some would think that the more neutrons the better, but it doesn’t work like this. Only a very small number of neutrons from fission end up causing another fission immediately. This is because the fission process with uranium, for example, highly prefers thermalized, or slowed-down neutrons. Fission neutrons are fast. So, these fast neutrons released from fission go through a moderator (usually water) to slow them down, so they have a higher probability of absorption by a uranium atom, causing fission.

In conclusion, even though it would seem the more neutrons the better, it is their quality and the specific characteristics they hold that make them a good fit. Fast neutrons will zoom right by uranium atoms without interacting, much like the world was doing to my firm before I embraced my niche. Thermal neutrons, though, almost can’t help but interact with uranium. That’s what I needed. I was looking for any neutron, but I should have been looking for the right ones.

In the United States, there are 55 commercial nuclear power sites. If each has about 800 workers, that’s 44,000 people. And I had at least something in common with all of these people. I understood their careers and job titles (and had held many of them). I appreciate and embrace the analytical engineering mindset. I had hundreds of contacts in the industry all over the country already. I am one of them. These were definitely the right neutrons.

In retrospect, I feel like I was dumb starting out. Even if I was wildly successful in meeting my goals, I still couldn’t even serve 1% of this audience. Being this focused still left so much room for me to be successful. In fact, with all my years in nuclear, going to events and plant assessments and peer group meetings, I had already met thousands of people, way more than my firm could ever take on.

Why didn’t I do this from the start?

Starting Over In A Niche

I immediately refocused. Not only was I going to embrace this niche, but I was going all-in. My goal consisted of two parts: (1) Make it so obvious that the firm was tailored to nuclear power workers (so that nuke workers would have no choice but to at least check it out), and (2) make it very obvious to those not from the nuclear industry that there may be a better firm out there for them (so that I didn’t waste my time with prospects who, like fast neutrons, would probably just pass through anyway).

Redesigning A More 'Natural' Website

Here is an early version of the website (embarrassing):

I took the website to maintenance mode, and immediately sunk the sailboat on the cover. (At this point, I am laughing at myself for thinking this would ever work!)

Here was the headline I realized I had been building for myself: “Nuclear engineer opens investment firm to serve the entire world. No one cares because he is still just a newbie in the industry.” Here’s what I wanted to headline to be: “Nuclear engineer opens The Only Financial Planning Firm in the World Created Exclusively for Nuclear Power Plant Professionals.” Now that might work.

I put those words on the website, superimposed in front of a picture of a nuclear plant. Subtlety is now out the window. I tore the site down piece by piece; it was actually fun.

Here is my current homepage:

I also created a video called Why Financial Planning for Nuclear Professionals Should Be Special and Unique outlining the planning process and placed it on the homepage.

If you looked at that title and thought it was a little strange, you are correct. Anyone not from nuclear power wouldn’t recognize what is interesting about that title. Anyone from nuclear would know that one of the Principles for a Strong Nuclear Safety Culture is “Nuclear technology is recognized as special and unique.” If a nuclear professional read that, there is a great chance they would get the wordplay.

Along with that, I added my former nuclear power credentials like my Senior Reactor Operator license, a picture of me in front of my former power plant, and other pictures that made sense, like a plant control room, gauges, etc.

I was committing to serve the nuclear community. It felt good. I felt reconnected, and also like the past 15 years hadn’t been a waste since I was still serving this community in some capacity. Website traffic went through the roof. Google Analytics provided good insight, but I also added a deeper website tracking program called Lucky Orange so I could see how people were interacting. I could actually view their interactions, a heatmap of the site, see if they watched videos, and much more.

I felt I had a purpose now, and was speaking to the community that taught me so many things, many of which were very transferrable skills (like risk management and attention to detail). It felt right. Previously, when I was marketing to everyone, it felt forced. This felt natural.

Systematizing The (Right) Process

Nuclear power is all about process. We have a procedure for everything, routine and emergency. Procedures are expected to be followed step by step, marking each as you go. If there is any discrepancy, stopping work is the only choice. The consequences are too great.

I wanted to recreate a similar environment in my business for several reasons. One, it would resonate with clients. The type of people that work in nuclear are analytical, love details, live for process, and want to know the “why” behind everything. They want things to be systematic. I am good with that. That is me. Also, it would ensure all clients went through the same process, from a quality assurance perspective.

I started by putting into place internal workflows for all aspects of the process. There was nothing particularly unique about the planning process, with the exception of timing. My process is very slow. Due to the analytical nature of my client base, it takes us longer to work through data, charts, graphs, assumptions, etc. Engineers and other scientific types can get caught in ‘analysis paralysis’, keeping them from making timely decisions. Time and repetition of information help break through that barrier.

I basically start with an intro and discovery like everyone else. We triage anything urgent, then systematically work through retirement, investments, taxes, education, risk management (insurance), and estate planning. As the firm grew, clients would talk to each other and ask, “Where are you in the process?” It was working.

This next part might be a bit crazy, and I am not recommending it to you. This would not work for most clients or advisers. What I am recommending is the spirit of this change: finding a way to make your financial process mirror your clients’ everyday work and what’s important to them.

I use two different financial planning tools… I use MoneyGuidePro (the Elite version) for Monte Carlo analysis and Income Lab for historical analysis. I like to see both methodologies. I run my client’s entire financial plans through both of them, analyze the discrepancies, and dig into what the different outcomes mean. I also use two different risk tolerance tools, TIFIN Risk (formerly Totum Risk) and Riskalyze. Most of the time they agree, but there may be instances where a particular question causes a big divergence in the results. I like to know that and use it as a conversation piece.

Yes, this is completely unnecessary for 99.9% of advisers. And inefficient. And time-consuming. It is literally double the work… maybe even more than double.

However, consider why. A nuclear power plant is built with systems in redundancy. If 1 pump is needed to cool a system, there are 4. There are fail-safes upon fail-safes. Although an accident is statistically unlikely, the consequences are too great to risk it. Just like running out of money in retirement has too many consequences. In the nuclear industry, it’s called the Swiss Cheese approach. One piece of Swiss has holes in it, representing risks. If something falls through the hole, it becomes an event. The more pieces you stack on top, the higher the odds that one of the subsequent layers is covering the holes above it, eventually making them smaller or covering them completely due to the random pattern. More layers equal more redundancy equals more protection.

Although this particular process may not resonate with your clients, it means the world to mine. The overwhelming feedback is that the redundancy built into the planning process reminds them of the redundancy of the power plant, and makes them sleep better at night. Finding a way to relate your planning process and make it appear very similar to your target market’s everyday processes is key; it builds trust and comfort with your clients (and soon-to-be clients). Since implementing this, more than 9 out of 10 people who started the planning process with me have become clients.

Rebuilding Presentation, Marketing, And Education Materials

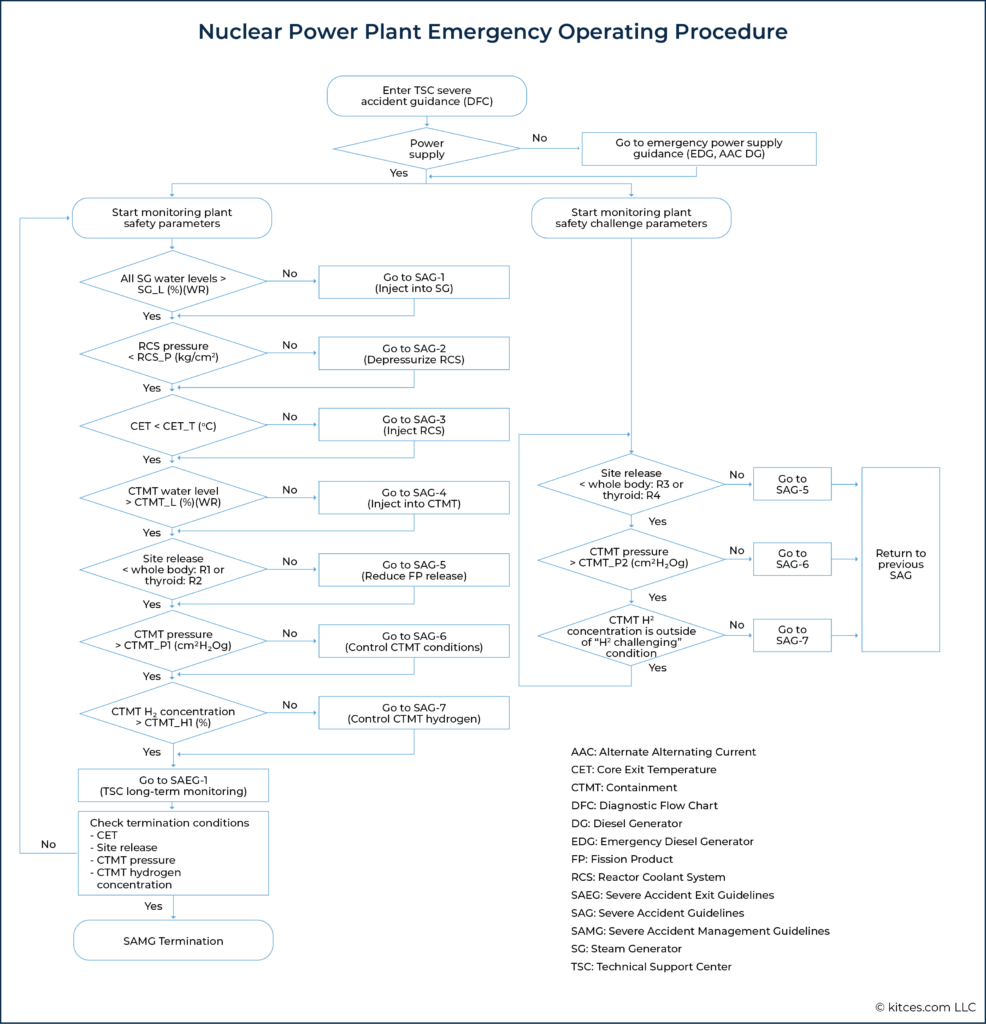

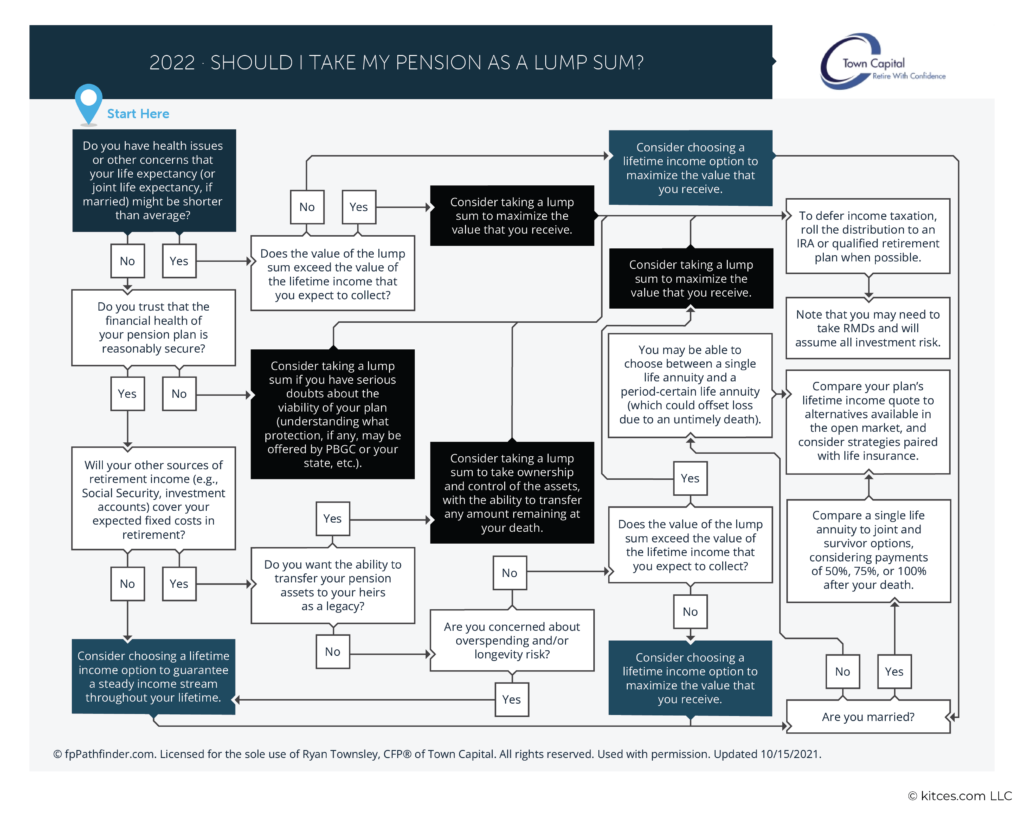

I also tried to make a lot of my presentation materials look like what my clients are used to seeing. This may be a little cheesy, but it also works. As I was exploring tools and solutions, I came across fpPathfinder. On its own, it offers fantastic tools that provide a lot of value to advisers and clients. However, at first glance, I knew it was a winner. Why? It looks like a nuclear power plant procedure!

It literally looks like an fpPathfinder flowchart. I rebranded them and, instead of Emergency Operating Procedures (EOPs), I call them Financial Operating Procedures (FOPs). Clients love it. They chuckle at it. But they also remember it.

One of my goals in this industry is to educate first. I love teaching. Knowledge is second to nothing. As a person who went through years of training to learn how to supervise the operation of a nuke plant, I realize the importance of knowing why you are doing something. We don’t push buttons blindly in a control room. I wanted my clients to learn the details of why we were making different decisions, not just because their adviser said so.

I created a Facebook group exclusively for nuke workers called Critical Finance: A Nuke's Guide to Financial Planning. Again, someone who looks at that title may see critical as meaning “important to know”. A nuke would see it as that, but also as:

Critical: The normal operating condition of a reactor, in which nuclear fuel sustains a fission chain reaction.

Another play on words, but it serves the purpose of speaking to the audience that I’m trying to connect with while knowingly not connecting as well with others (who can just find their path to a different advisor, because they’re not a good fit for my process anyway).

I made a pledge in my Facebook Group: “Absolutely no selling or pitching.” I host live webinars on various topics like withdrawal rates and Roth conversions, then post the replays. Only nukes are allowed, the group is private, and I do the necessary due diligence prior to allowing admission (this is a must, because I get 2-3 people from the finance industry per day trying to join as well!)

If a group member contacts me and wants to talk, that is fantastic (and yes, it is the ultimate goal.) However, if someone wanted to watch my material for the rest of their life and never contact me, I’m okay with that, too. I cannot tell you how many referrals I have gotten from someone who is a DIYer. They didn’t need my help and would never hire me… but when the DIYer’s friend was looking for someone, they referred me solely based on the content I have been producing to educate them.

Critical Finance has 115 members. About half of these are clients. Of the 50 that are clients, 10 of them weren’t clients when they joined the group. They contacted me when they realized their advisor wasn’t doing the things I was talking about in the webinars. These webinars are an incredibly efficient way to communicate what we are already doing for clients on a recurring basis.

For the other half who are not clients... maybe they will be someday, or maybe they won’t. But you don’t need very many people in your Facebook group when you’re so focused that nearly 20% who join (12 out of 60) become a client! And ironically, if they all decided to become clients tomorrow, I could not handle the influx anyway.

The main thing I learned, though, is that none of these people would have joined the group had it been a general finance group on Facebook. There are thousands of them. Way too much noise. They joined because it was for them, exclusively. And a big number of them have now become clients because I serve them exclusively.

To Niche Or Not To Niche – Takeaways

So, what should you do differently? It really depends. Niches are not for everyone, and it is okay if that is not your vision. However, consider the efficiency you gain with a more niche focus, and how it helps both you and your clients.

I work with people who have relatively similar mindsets. I can say there is a high probability that if I present in a particular way to them (high detail, redundancy, facts and figures, etc.) then they will respond favorably. There are only so many nuclear companies out there and I worked for the largest, so I know their 401(k) plans, pensions, and benefits very well. (Tip: I have offered a free financial plan to people employed by a large nuclear utility company that I was unfamiliar with just to gain access to the available 401[k] plan investment options, pension plan guidelines, and other benefit details so I could reach out to other employees with specifics rather than generalities. It works.)

With the efficiencies that come from having a consistent clientele who don’t have a lot of variability amongst themselves, I am able to spend less time sifting through new data and information, like company benefits, and can more quickly provide better recommendations to clients. This makes more time available to work on their planning, to work on the business, or to be with my family.

If I were to sum it all up into a few bullet points of what worked for me:

- Speak to an ‘uncomfortably’ small group of people, as long as there are enough in the group that you could build a business that would make you happy and successful. People are intuitive. If they sense you are committed to them, they are more likely to commit to you. If you commit to everyone, that isn’t a commitment at all. And because it only takes 100 or even just 50 great clients to have a successful business, you really can be remarkably ‘narrow’ and still have more than enough prospects to be successful.

- Make your financial planning process resemble a process that your target market is used to; it will be easier for them to relate. Use subtle (and sometimes not-so-subtle) ways to recreate their daily routine into your financial planning process to create familiarity.

- Don’t be afraid of being overly cheesy with how you incorporate terminology, visuals, and jargon from your target market into everything you do. Wordplay works. Give them a reason to stop scrolling. Even if they laugh, they will remember you.

These three simple things made a huge difference in my firm, my success, and my happiness. My first year in business, the firm grew to $8M in AUM (the first half of that year, while still operating under the 'Bland Brand’, AUM was only $500k.) In the second year, it grew to $18M in AUM. In the 3rd year, $48M, plus a considerable portion of "fee" business not related to AUM.

I am the only person at the firm: no assistant, no paraplanner. However, due to the efficiencies of having strong processes, working with like-minded clients, and committing to a particular niche, I am far from overworked. I vacation regularly, work a normal schedule, and genuinely enjoy my work-life balance.

I live by this motto, “The key to success is being pleased and proud, but never satisfied.” Give yourself a pat on the back occasionally. Celebrate. Then get back to work and find something to improve.

Don’t give up. You can do this.

Leave a Reply