Executive Summary

In the span of barely 10 years, companies like Uber, Airbnb, Facebook, and Alibaba have experienced explosive growth, far surpassing the growth rate of their respective industries, and despite the fact they don’t actually produce anything themselves.

Yet in fact, that’s the whole point; they are platform businesses, and their role in facilitating a marketplace between consumers and producers is the primary form of value creation, not the production of goods and services themselves. In the process, these platform businesses have been out-competing or outright disrupting their respective industries, raising the question of whether – or when – the platform model will come to financial services as well.

In point of fact, though, the financial services industry is already filled with platform businesses. Arguably, stock market exchanges are one of the oldest and original types of platforms to connect buyers and sellers. And custodians and broker-dealers constitute a form of platform business as well, connecting advisors and the asset managers who want to reach them. Envestnet is quite possibly an even purer form of platform business, avoiding the hassles of actually being the custodian or doing the clearing, and instead just serving as technology that facilitates the matchmaking process between advisors and asset managers.

Still, this means the door remains open for an actual financial advisor matchmaking platform, that connects consumers directly to financial advisors themselves. Prior attempts at this model have largely failed, likely due to the fact that most advisors are such generalists that it’s not really feasible to match them effectively with consumers in the first place. In turn, this suggests that a successful platform in the future will need to focus not on pairing consumers with advisors, but on helping consumers find an advisor who can answer their particular question – which forces advisors to actually choose a niche specialization by which they can be matched. Which means in the end, the real platform opportunity of the future is not a financial advisor platform, but a financial advice platform instead!

The Rise Of The Platform Business Model

For most of history, the traditional business model has been some form of pipeline business – one where the consumer buys a product or service that is delivered by the business in a series of linear steps from one end of the pipeline to the other. With a relatively simple product or service, the consumer may buy directly from the original producer. In more complex businesses, the pipeline may be elongated, with one company designing the product, the next manufacturing it, and another distributing it for sale, and each business adds some value (and earns its keep) along the chain.

In the past decade, though, we’ve witnessed the emergence of an entirely new model: the platform business. The key distinction is that while pipeline business models are limited to how quickly producers can create a good or service and push it through the pipeline, the platform business uses technology to connect consumers and producers directly (and take a small slice of the transaction). The key distinction: by “merely” being the connector of other buyers and sellers, without being in the business of buying and selling directly, platform businesses can grow and scale far more rapidly than was otherwise possible with any business model of the past.

Thus, in the span of barely 10 years, some of the world’s largest companies have grown “out of nowhere”, dominating industries with companies that have been around for decades, despite the fact that the upstarts do not actually produce any goods or services. As Tom Goodwin recently noted: “Uber, the world’s largest taxi company, owns no vehicles. Facebook, the world’s most popular media owner, creates no content. Alibaba, the most valuable retailer, has no inventory. And Airbnb, the world’s largest accommodation provider, owns no real estate. Something interesting is happening.” The key driver that makes the platforms so extraordinary: “network effects”, or the phenomenon that the more people use the platform, the more desirable of a marketplace it is for other people to use.

Which raises the question: what industries will be impacted next? And is it only a matter of time before the platform business model consumes the financial services industry, too?

Financial Services: The Original Platform Businesses?

Notably, from the perspective of bringing together buyers and sellers in a central marketplace, arguably the financial services industry is the original platform business. After all, matching buyers and sellers is exactly what the stock market – or more specifically, the stock exchanges – were established to do. In this context, arguably most of the financial services industry itself is simply a collection of the ancillary businesses that support the stock exchange platform business. Apple and Facebook have “app” makers; the stock market has investment banks and broker-dealers.

Notwithstanding the fact that the stock market itself is one of the oldest and largest platform businesses, though, there are other platform businesses within the industry that help to facilitate interactions (i.e., transactions) between producers and consumers as well.

For instance, custodians and independent broker-dealers serve as a form of platform, facilitating interactions between advisors and their suite of available products; notably, while consumers are the ultimate end-buyers of those financial services products, in this context the custodian or broker-dealer platform is the intermediary between the advisor and the product manufacturer themselves. Thus, just as Upwork connects businesses to freelancers, and provides a platform to help facilitate those transactions and the associated workflows, so too do custodians and broker-dealers offer a suite of technology tools (e.g., trading and rebalancing and portfolio accounting software) to help facilitate the transactions that advisors engage in via their platforms.

Perhaps an even better example of a platform business serving financial advisors would be Envestnet, which similar to broker-dealers and custodians facilitates financial advisors connecting with asset managers for various types of investment solutions. What’s notable about Envestnet from the platform perspective, though, is that they don’t actually serve as a broker-dealer or custodian at all; in fact, they work with those companies as a technology layer on top, using their technology to facilitate connections between advisors and third-party investment managers. The end result: Envestnet has $880 billion of platform assets, of which it only actually manages barely 11%; the remaining 89% are all under “advisement” and licensing fees for being the platform that connects advisors to other investment management solutions. And Envestnet’s ongoing technology acquisitions, from Tamarac to FinanceLogix and then Yodlee, have all helped to make it into an ever-larger platform, with a growing suite of technology tools to help facilitate more platform interactions.

Notably, though, it’s not the mere presence of technology that establishes a “platform”, but its ability to perform a matchmaking process. Pure financial advisor technology platforms, from financial planning software platforms like eMoney Advisor to CRM-based platforms like Salesforce Financial Services Cloud or the new FinLife Partners to portfolio-accounting and investment based platforms like Orion Advisor Services or Morningstar’s Advisor Workstation, may help make financial advisors more productive, but their ability to add value is contingent on the effectiveness of the advisor’s pipeline business in the first place. They cannot naturally scale the way pure platforms can, as technology to augment advisors is still ultimately constrained by the ability of the advisors to grow their own businesses.

Will There Ever Be A Financial Advice Platform In The Future?

While custodians, broker-dealers, and especially companies like Envestnet function as a form of platform business between financial advisors themselves and the financial services product manufacturers trying to reach them (and their clients), they are not actually platforms that facilitate consumers finding a financial advisor, where “advice” itself is the value interaction. But could there ever be an actual “financial advice” platform business that matches advisors and consumers, akin to how Uber matches drivers and riders?

In point of fact, some have tried in the past to build such a platform. The closest representation of the model was MyFinancialAdvice, an initiative that begin in the early 2000s but ultimately shut down a few years ago after failing to get sufficient traction with consumers. Another example still in practice is Paladin Registry, which also provides a “matchmaking” service between consumers and financial advisors (which the platform helps to vet on the consumer’s behalf). And several membership associations and advisor networks provide their own form of “mini”-platform for consumers to find an advisor, including the NAPFA “Find An Advisor” tool, the CFP Board’s “Find a CFP Professional” site, and the find-an-advisor capabilities of the Garrett Planning Network and our own XY Planning Network.

Some might suggest that the various “robo-advisor” solutions are also functioning as platforms, but in reality their managed-accounts solution is far closer to a traditional pipeline business than a platform model. Companies like Betterment and Wealthfront (and while it was still independently owned, FutureAdvisor) ultimately construct their own portfolios, and what they sell to consumers is their (automated investment) portfolio construction services, produced by the robo-advisor and directly delivered by the robo-advisor. In turn, this means that robo-advisors must ultimately still market to consumers like any/every other pipeline business trying to distribute its products or services to the public, and there are no prospective network effects; while a larger customer base can mean some economies of scale, and potential referrals, the robo-advisor “platform” value interaction itself does not become more valuable with more users (unlike a service like Uber, where more riders means more demand for drivers, and more drivers means faster response times for riders, a network effect virtuous circle).

On the other hand, there are a few technology firms that have at least tried to initiate a bona fide form of platform business for at least some aspects of investment management services. Motif is arguably a form of platform business after it pivoted early on from designing its own motifs to allowing others to create them – which means the platform now connects Motif designers to investors who want to buy those motifs, in a relationship that can at least potentially exhibit network effect benefits (as more investors create demand for more motifs, and more motif demand creates more income potential for motif creators, in a virtuous circle). Similarly, Wealthfront’s predecessor business model KaChing also operated as a platform that connected consumers to others who managed investments so they could mirror the trades themselves (a rough version of Envestnet but for investment managers going directly to consumers, rather than to advisors), though the company ultimately pivoted away after failing to attract substantial assets to the platform.

Again, though, even these robo-advisor solutions ultimately are (or at least were) still trying to build platforms to connect consumers with investment managers where the value interaction was portfolio management and investment selection, not more holistic financial advice, and certainly not a matchmaking service to connect to advisors themselves.

Why Aren’t Financial Advice Platforms Working Now?

Given the potential for a matchmaking platform to connect consumers with financial advisors, the question arises as to why such a platform hasn’t taken off already.

Prior advisor matchmaking platforms have seemed to fail because they couldn’t get consumer traction, in a world where client acquisition costs are already a significant inhibitor to expanding the reach of financial advice. Notably, this also implies that there was a failure for any network effects to help the platform gain traction, which can either enhance the value interactions on the platform (giving the platform more revenue to market) and/or bring down the acquisition costs (as the increasing value and usability of the platform spreads by word of mouth).

In practice, though, an added difficulty for most financial advisor matchmaking platforms today is that it’s hard to match a consumer to an undifferentiated, generalist advisor in the first place. The lack of any kind of niche or specialization for most advisors means there’s no useful criterion to match the advisor to the consumer. And the relatively small number of clients per advisor, even for an established advisor, means it’s virtually impossible to reach a critical mass of advisor ratings/reviews. The end result – most advisor matchmaking sites end out matching consumers to advisors based on location, even though an advisor’s zip code has no practical relationship to whether the advisor can effectively solve the consumer’s financial problem.

At best, the few matchmaking sites that tend to do the best now are the ones that have some kind of differentiating criterion that makes the advisor eligible to be on the platform in the first place – as NAPFA only matches consumers to “fee-only” advisors, the CFP Boar only matches to CFP Professionals, the Garrett Planning Network provides matches for the middle class looking for hourly advice, and XY Planning Network helps Gen X and Gen Y consumers find an advisor who works for a monthly fee with no asset minimums.

Arguably, though, perhaps the biggest failure of prior financial advisor platform attempts was that they tried to match consumers to a financial advisor, instead of matching consumers to the financial advice that answers their questions. Because the reality is that most consumers don’t wake up in the middle of the night saying “I need a comprehensive financial plan” or “I’ve got to find a financial planner”; instead, they wake up sweating a particular financial question, from “will I be able to afford to send my kid(s) to college?” or “am I making the right decision about starting Social Security now?” or “should I refinance my student loan debt?”

In this context, the key value interaction on a financial advice platform would not be helping consumers to find an advisor, per se, but helping them to find an advisor who can answer their pressing financial question. This also helps to explain why “financial advisor review” sites have also failed to gain traction; because consumers aren’t looking for advisors (and their ratings and their geographic location and their undifferentiated "we specialize in everything"), they’re looking for answers to financial questions (that might be provided by a particular advisor). In turn, this implies that what the financial advice platform must do well is match consumers with a particular question to the specific financial advisor who has the specialized expertise to answer that question.

Dear fellow financial advisors: this is why we can't have nice things. #CantSpecializeInEverything #NotCredible pic.twitter.com/4NdZdScwMu

— MichaelKitces (@MichaelKitces) May 7, 2016

Notably, this is exactly how most other advice platforms operate when it comes to other professional services as well. While financial advisors almost always start by offering “comprehensive financial planning/advice” even if that makes it harder for consumers to tell us apart, sites like RocketLawyer offer an “Ask A Lawyer” service (not a “Find A Lawyer” solution), and ZocDoc does pair consumers up directly to a doctor, but the first question is “what doctor specialty” is the consumer seeking? Matchmaking goes to solving the question/problem first, and introduces the professional service-provider later.

How Would A Financial Advisor Platform Business Work?

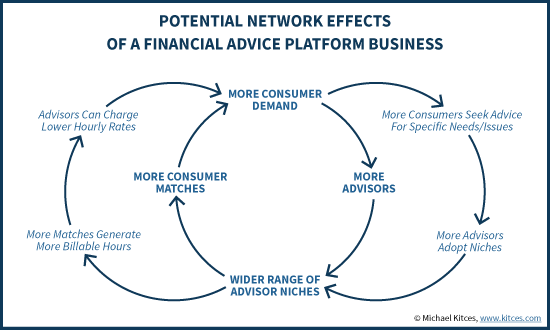

These dynamics of consumers searching for advice, not advisors, suggests that the true “financial advice platform” business of the future will most likely be a matchmaking platform between consumers and financial advisors with various specialties – i.e., niches – that make it easy to identify which advisor is the right match for the consumer’s question. The key criterion for success will be bringing together a critical mass of advisors who all have specialties individually but in the aggregate have enough breadth to answer a wide range of consumer questions. In turn, the breadth of answers can attract consumers to the platform to get their questions answered, and the greater demand for advice draws more advisor specialists to the platform, and gives them more opportunities to deliver that advice, in a virtuous circle.

Notably, in a world where the biggest challenge for advisors to specialize is finding enough clients to fill their potential “billable hours”, a growing level of consumer demand for advisor specialists – facilitated by the platform itself – would make it easier for advisors to specialize, and even make it feasible for them to charge lower rates. After all, while hourly financial planners commonly charge as much as $150 - $200/hour, an advisor specialist who was “assured” of getting 1,000+ billable hours could make $100,000 charging “just” half that hourly rate (and still have the other half of their year available to build the rest of their business). And such demand for advisor niches could itself help to persuade more advisors to adopt a niche!

Fortunately, though, to the extent that the financial advice platform encourages and drives advisors towards niches, the advisors will be easier to match in the first place, solving the fundamental problem that exists today: advisors aren’t differentiated enough to be matched based on anything but their geographic location, driving up the cost of client acquisition and the cost of financial advice in the first place. Which means in the long run, solving the matchmaking problem between consumers and financial advisors can not only make it easier for consumers to get their questions answered, but make it less expensive, too.

So what do you think? Do you think a financial advisor - or financial advice - matchmaking platform would be viable? Would you participate on such a platform, if you had to actually pick a specialization to focus on? Would matching consumers based on their financial questions be more effective than trying to match advisors based on geographic location?

“the key value interaction on a financial advice platform would not be helping consumers to find an advisor, per se, but helping them to find an advisor who can answer their pressing financial question.” …This is what we’ve built in http://www.Wealthbase.com …In launches later this year.

I just took a quick look at this website. As a 40-year-old female planner, I was struck that the advisor you chose to include in this video was the stereotype: a middle-aged-or-older white dude in a suit. To be sure, that stereotype reflects current reality. But don’t we all bemoan this lack of diversity in the profession? I would have loved to see some variation from the advisor stereotype in that video. Advertising women and minorities and younger advisors as the face of the industry is the way we *attract* women, minorities, and younger people to the industry. Maybe there will be more videos on the site that can feature other more diverse images of advisors?

We can’t help the fact that many financial advisors match the demographic of the character in the video. Sorry if you were “struck” by that. And, we’re just as interested in promoting the “face” of diverse consumers to attract to our site when we launch, not just the financial advisor depicted as the “middle-aged-or-older white dude in a suit” as you say, which is why we cast a Hispanic woman and her Hispanic child as representing those consumers. And we also cast another “ethnically ambiguous” (a casting term) woman in the executive role of a manager overseeing financial advisor interactions with consumers at the enterprise level in that video.

I actually am a middle-aged white guy and even I found that response a bit harsh. Next time you might want to say something like:

“Thank you for your comment, we’ll make certain to consider the increasing diversity of Advisors”

…or maybe…

“Our industry’s lack of diversity is an unfortunate hindrance to helping match investors with the Advisors they seek. As our product grows, we’re hoping that it will help solve this problem.”

I think Meg’s comment is indicating another powerful reason why our industry hasn’t seen as much success developing modern, digital platforms. The businesses Michael mentions in the article serve a radically diverse clientele with products and services that are designed, in some way, to support or accept such diversity. They are operating in, or have created, an entirely different sort of environment.

Here’s a FinTech company I am starting to follow that has great potential. It will help advisors automate the fixed income side of their clients’ portfolios. BondIT http://www.bonditglobal.com/

Since most successful advisors build their business on introductions and to a lesser extent referals, these type of sites are more useful for beginning advisors and for advisors who only work on an hourly basis and who lack skills in prospecting. If you are truly doing holistic planning, why would you pay for this type of service.

Perhaps advisors build their businesses on introductions and referrals BECAUSE there’s no effective clearinghouse to match consumers to advisors, forcing them to rely on time-intensive inefficient in-person marketing strategies instead… 🙂

– Michael

There are different ways to look at time spent on prospecting. I prefer a client to come in as an introduction versus lead through a website. I have much lower client acquisition costs on an introduction. I will spend less time making the client comfortable, much easier to connect, much higher chance the client will trust me and disclose me most of their assets and issues. Client that comes in as an introduction is also more likely/easily to refer me to others. I will spend less and less time over time prospecting.

The lead I get from a financial super website is someone who instead of asking their friends for recommendation to their advisors is googling for a solution. even if they become a client, they are less likely to refer me and I have to spend time to teach them how to introduce me to others. At the end of the day, they may be happy with me and refer all their friends to the website instead of me directly. I have lower margins in the long run if a client comes in through a lead versus introduction.

There are incentives for beginning financial advisors to use these sites but over time if they become succesful, they realize they have lower client acquisition costs in the long run through other means.

It is easy to build a lead site that generates quotes for car insurance, much harder to generate leads for long term care issues for a married couple with 3 kids when one of the in laws is moving in. Would you really go on to the web and look for a financial advisor if you suspect your parents has dementia or how about when one spouse has a terminal illness. Most people in these cases ask for their friends in finding a financial advisor. I don’t think you can build a web site that can make people comfortable in looking for advice in cases like these.

Michael,

I agree that large scale institutionalized support for fiduciary counsel that supports professional standing in advisory services based on objective non-negotiable fiduciary criteria authenticated back to statute. This is because there are issues beyond the control of advisors which must be managed like (1) treating trade execution as a cost center to be minimized as required by statute (2) adoption of a prudent process (asset/liability study, investment policy. portfolio construction, performance monitor) authenticated back to statute,.which definitively establishes professional standing.(3) retooling of the brokerage product menu proving access to real time holdings data essential for continuous comprehensive counsel required for professional standing (this is highly disruptive to expensive packaged product the packaging of which make it impossible to manage client holding data).What is needed is a large scale advisory services firm (Luminous, CapTrust, Dynasty, HighTower to evolve an entirely different advisory services business model and enabling technology which outdates the conventional brokerage support of advice. The DOL is moving the industry in the right direction, the question is will any brokerage centric organization take the culturally difficult steps in the best interests of the investing public, or will b/d’s continue to stop at nothing to thweart innovation. SCW

This is a super good article! I tend to get a lot of financial adviser companies and and CRM people.

https://chrome.google.com/webstore/detail/callndr%C2%AE-call-talking-hea/jaijncdnkdmebcpgihfdmpibhkffddgi?hl=en

It already exists, it’s called “Google” :-). You are better off figuring out how to make Google point to you when the right question is asked (e.g., in your niche), than waiting for some matching service to gain traction.

With that said, imagine if Google created a Mint like service for account aggregation. Think about how they could use that information to provide even more customized answers to your questions. And target their adsense to an even scarier degree.

I agree. I’ll highly specialize a blog posts along with Youtube video (to increase rank) to reach a targeted audience. Works like a charm. Just need to know what they are asking.

The dating model applies to many industries. In general, it works best for consumers with lower discrimination and/or the consumer with infrequent need. For example, you may go on match.com and it’s a free-for-all. Then there are services like “its just lunch” and others for the more discriminating “buyer.”

So a person that inherits money or retires and gets a lump sum but has done little if any investing prior would be a perfect candidate.These people would also not know enough to seek out a specialty. These people are also infrequent users, much like the person who would call 1-800-dentists. Clearly, these people have not had their teeth cleaned every 6 months.

The lawyers who advertise on late night TV do advertise a speciality (injury, divorce, specific-issue-class-action) as the public is aware that the legal professional has specialities. Not so with financial advisors–the public has little to no understanding of any specialty or categorization.

Paladin is a very good example of the dating model for financial advisors. But to reach the less-discriminating consumer, the marketing needs to be on TV. So unless a platform comes to the business with sufficient capital, the matchmaking in the financial advisory business will remain fragmented.

Thanks for this great article. You’ve summarised the challenges we’ve been facing for the past 9 years building and growing Planet of Finance. Planet of Finance is a network that regroups independent finance experts (including Lawyers,HR firms and specialised IT firms) on a global scale. We started off as an online M&A tool for financial advisors and have grown into the largest social network for private wealth professionals. Our experience in Europe and Asia tells us that most wealth professionals are looking for expansion channels and client acquisition opportunities. We successfully created an alternative to the usual lengthy face to face meetings required to drive expansion opportunities by creating a global and secure online network. Today, our ambition is to remove the frictions in customer acquisition and lowering the cost to almost zero. We do this by democratising access to financial services to the largest client base possible and by intelligently matching client requests with a pool of global wealth professionals through our online tool (you can learn more about us here: http://www.planetoffinance.com).

Although this post is quite old now, it still holds true. And we at Zoe are hoping to change the game. We offer a bespoke matching service for clients and financial experts (financial planners, advisors, insurance experts, etc.). We too realized that there was no such platform available in the market. To overcome the obstacles that you mentioned in your blog, we are targeting high earning young professionals who perhaps don’t own many assets (yet), allowing financial experts to start working with these people now, with the idea that their wealth will grow. However, we are not boxing our clients into this category at this stage. It’s our current target market but we may find that this changes based on what our data shows us as we grow.

From a consumer perspective, it is very difficult to find trusted financial advice. So what we do is vet the experts on our platform. We are VERY strict about who is able to join, and we don’t charge a fee. So we don’t have an incentive to add hundreds of advisors to our platform, our sole goal is to have the best people on the platform. The matching process is then managed by matching the client’s specific needs (as you mentioned they don’t necessarily want a comprehensive financial plan) with what the advisor can offer them and help them with. We speak to the client and discuss exactly what they are looking for, pitch this to the advisor that we feel is best suited, if they are happy to proceed we then introduce the parties. The client interviews the advisor and if they are happy they work together. If not, we find someone else for them. As a few people have mentioned below. client acquisition costs are high for advisors and introductions are generally much more valuable as they save time and have a higher conversation rate. So we fill that need for advisors. And from the other side of the coin, there are clients that need good financial advice from experts that they can trust, but they don’t know where to begin or how to know if they can trust them – which we make sure they can.

http://www.zoefin.com

Michael-what is the difference between Orion and Envestnet as it relates to a platform? In other words, why isn’t Orion a platform?

Do we really even need financial advisors?

I second that on your thought. We have to keep in touch with doctors no matter how minor the issue be. Such that in case with hair and skin issues, we should be bounded to at least consult with a best dermatologist nearby once so that the precise problem may apparent. Best Dermatologist near me Pakistan

Very much true, digitalized world has given us much too much bliss, making our lives comfortable. The most frequent element of this new realm are the websites and there is availability of bulk companies in Pakistan who are well known in developing best websites.

I love your work here, honestly, you are the best. Your words can simplify the confusions that we had during figuring out the best fast food deals. best pasta near me