Executive Summary

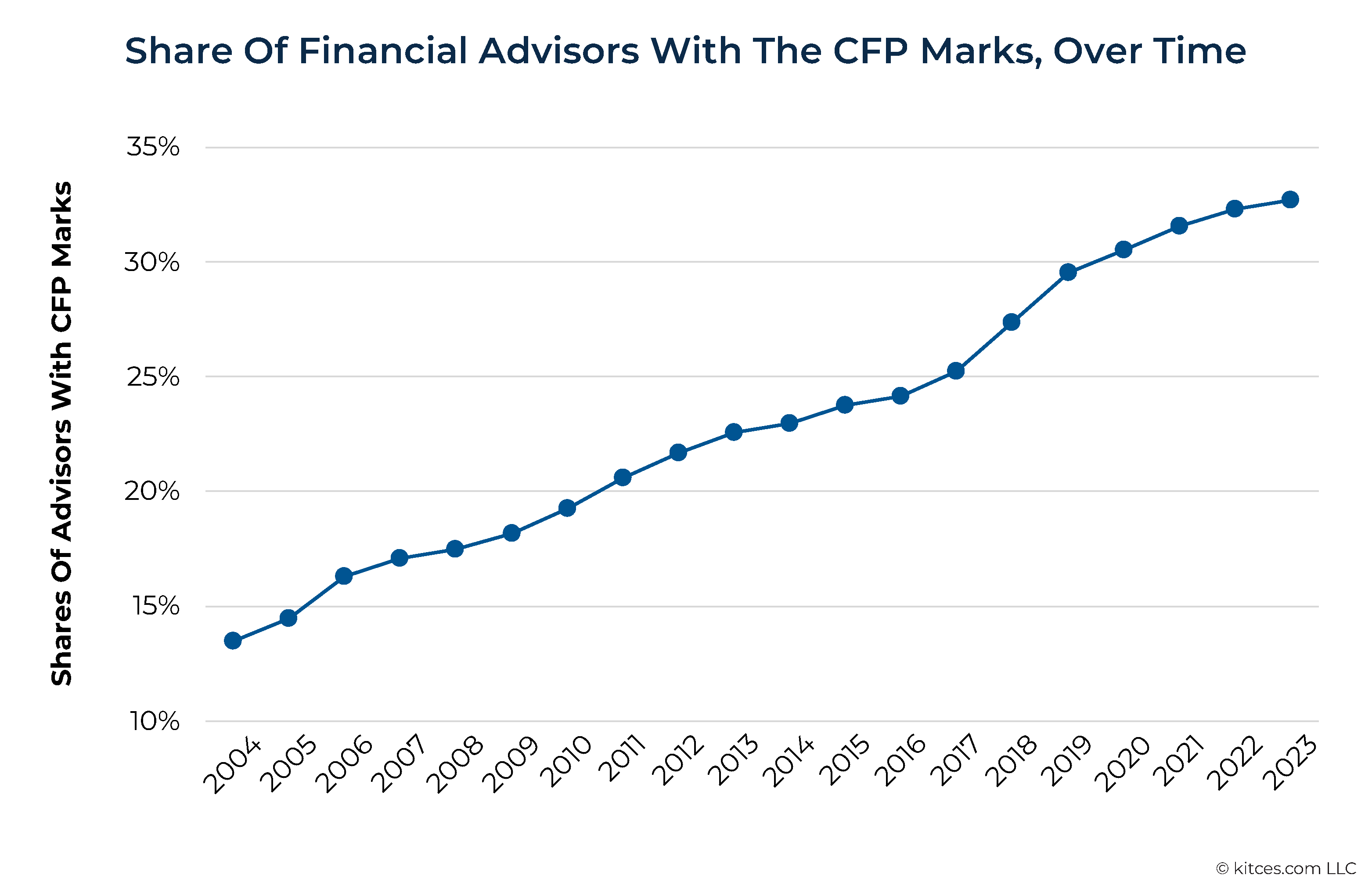

While the share of advisors with the CFP marks has risen steadily over time, today, about 2/3 of financial advisors are not CFP professionals. This means that, for most advisors, the decision to obtain this designation remains an open one. A crucial factor in an advisor's decision to prepare for the CFP exam – often requiring them to sacrifice evenings and weekends to complete the requisite coursework (which can take more than a year), and spending many thousands of dollars – is whether they will actually earn more as a result of doing so.

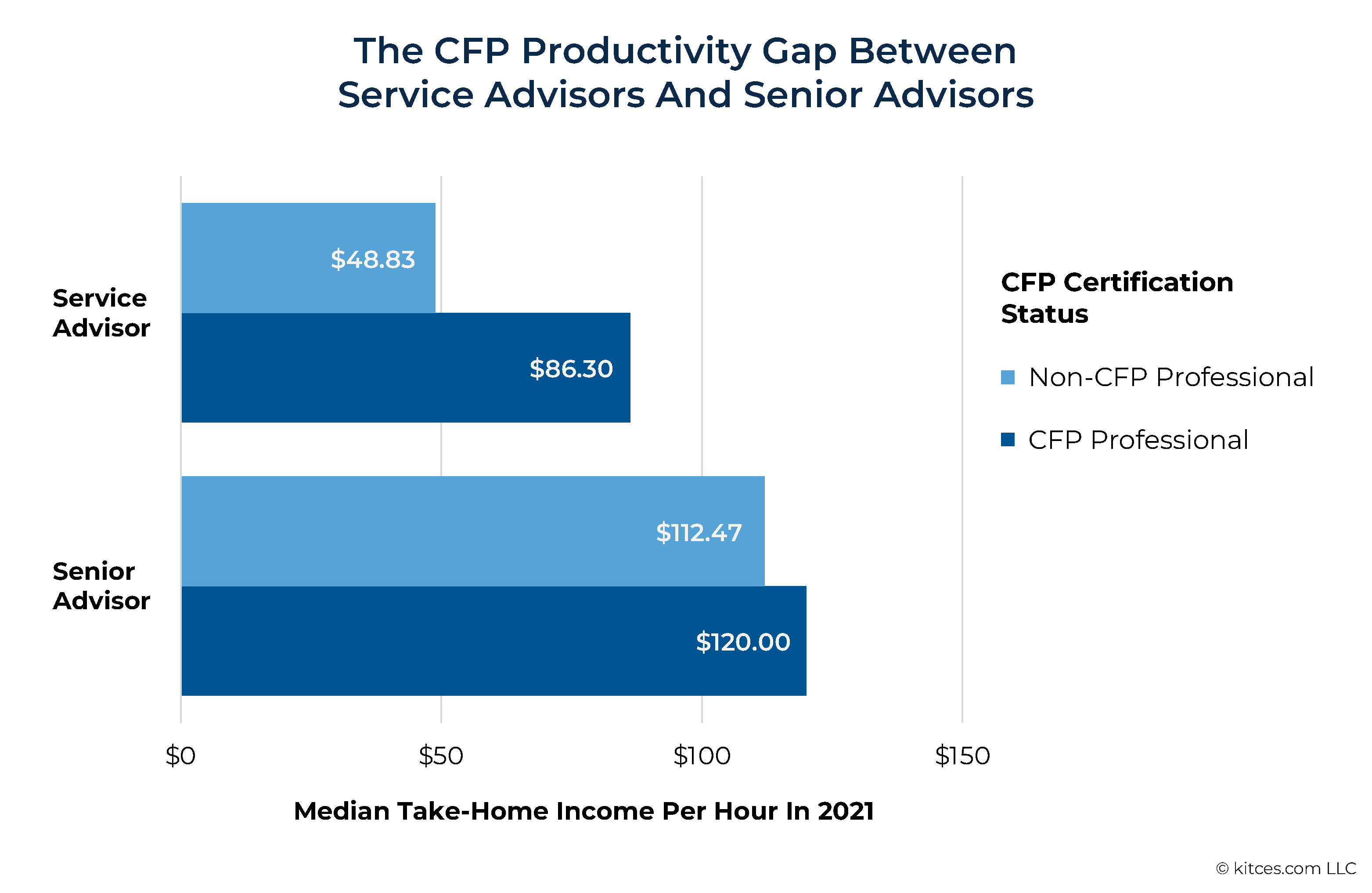

According to the 2022 Kitces Research Study on Advisor Productivity, CFP professionals take home more money per hour worked than non-CFP professionals, with this gap being substantially larger for service advisors than senior advisors. The typical service advisor without CFP certification earns $48.83 for every hour that they work, compared to $86.30 for service advisors with the CFP marks – a difference of $37.47, or a whopping 77% boost in income per hour! The typical senior advisor without the CFP marks earns $112.47/hour, compared to $120.00 for CFP professionals, a far more modest difference of only $7.53.

In this article, Michael Kitces and Mark Tenenbaum (Director of Advisor Research) explain this disparity in earnings per hour – dubbed the "CFP Productivity Gap" – and how it appears to be driven by explanations stemming from both the skills that CFP practitioners develop and deliver (supply-side explanations), and the preferences of clients – especially more affluent clients – when selecting an advisor to work with (demand-side explanations).

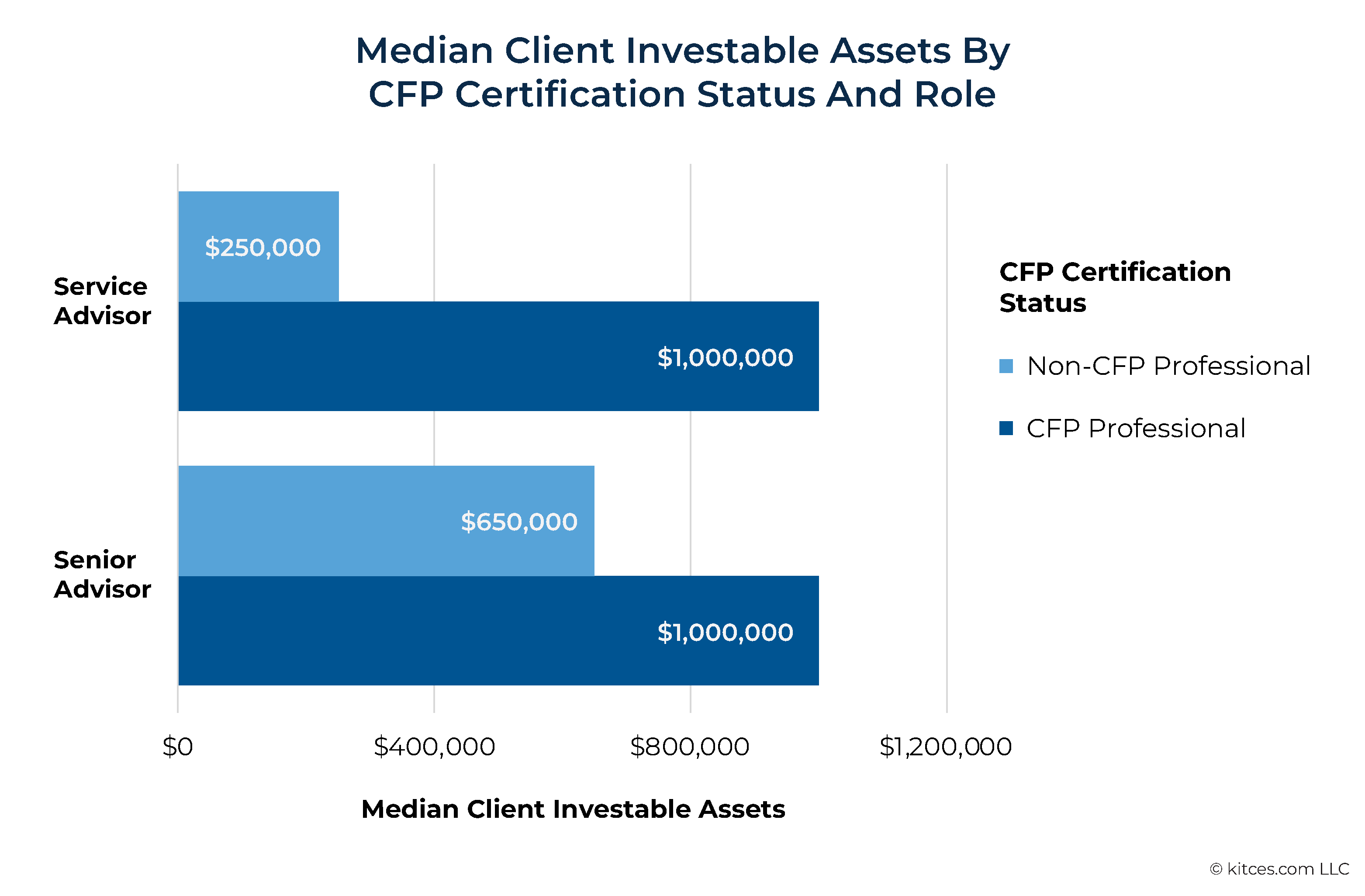

Specifically, service advisors with the CFP marks appear to spend more time on key revenue-generating activities such as meeting with clients and prospects and generating financial plans, and that these hours are put to good use because those CFP professionals both offer financial plans that are more comprehensive and update clients' financial plans more frequently than non-CFP professionals. As a result, teams with service advisors who hold the CFP marks tend to attract significantly more affluent clients than teams with non-CFP certificants, with a median client AUM of $1,000,000 AUM versus $250,000 AUM, respectively.

These wealthier clients also tend to pay substantially higher fees, which has a key implication for firms looking to attract and retain affluent clients: hire CFP professionals or help existing employees who have yet to earn their CFP marks obtain them. The knowledge obtained through CFP certification can forge a more planning-centric practice, offering financial plans that are more comprehensive and updated more frequently – which are clear value-adds for high-net-worth households who often have complex planning needs. Crucially, the research shows how the cost of employing CFP professionals (who command higher salaries than their counterparts without the CFP marks) is substantially lower than the revenue firms generate by employing them.

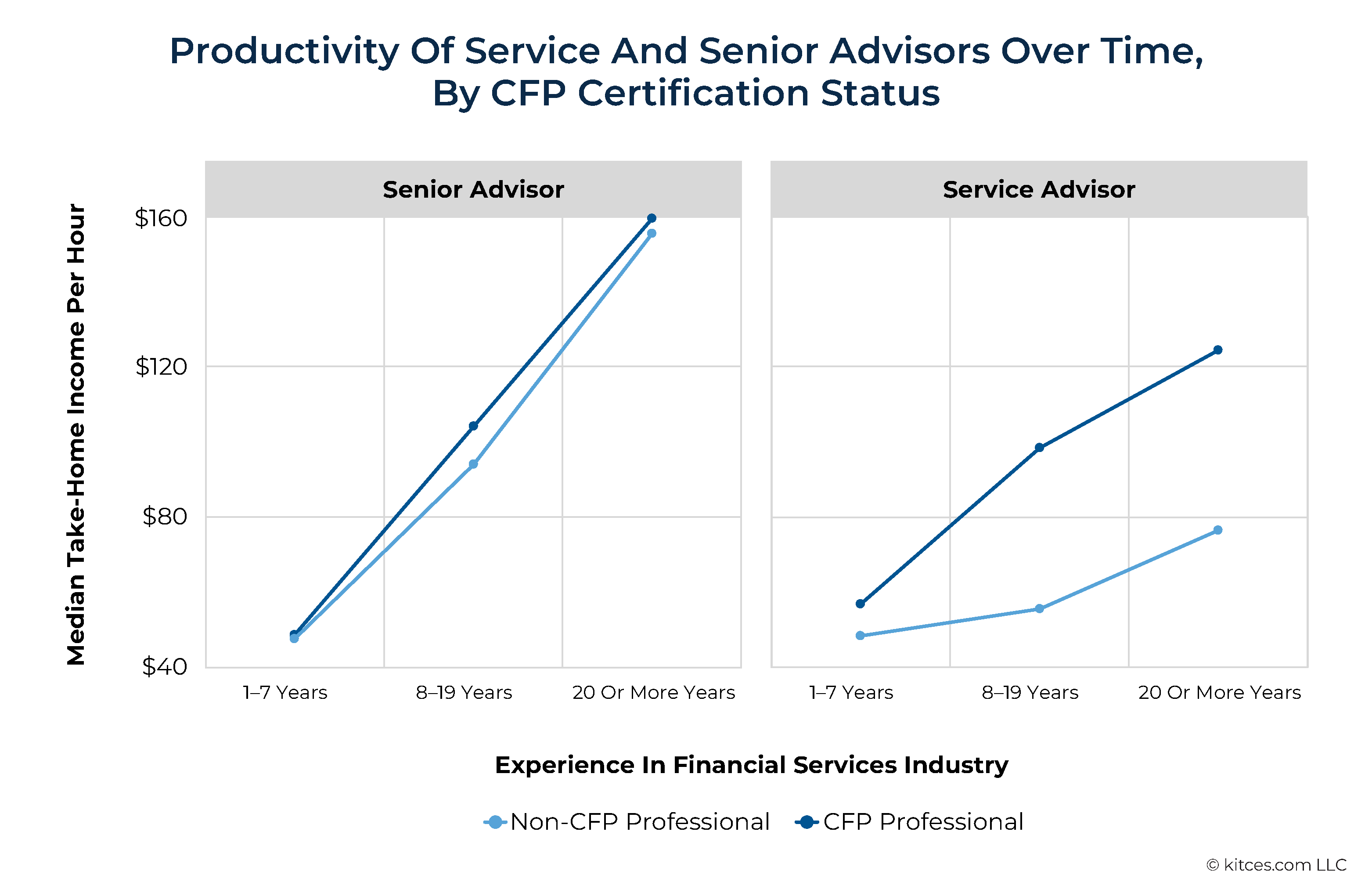

The CFP Productivity Gap also has profound ramifications for the income growth of service advisors throughout their careers. While senior advisors tend to see income growth over time regardless of their CFP certification, non-CFP professionals fall farther and farther behind their counterparts who are CFP practitioners over the course of their careers. Indeed, for service advisors, the CFP Productivity Gap grows from an earnings difference of $8/hour for those with less than 8 years of industry experience to over $50/hour (which adds up to $100,000+/year in greater earning potential) for those in business for 20 or more years. Hence, CFP certification appears to be a crucial vehicle by which service advisors can experience continued income growth over time without stalling out.

The key point is that service advisors earn substantially more by obtaining the CFP marks and firms are likely to benefit from supporting them in doing so. This helps the firm expand its teams of service advisors who can take on and support the firm's most high-dollar clientele. Which, in turn, frees up the capacity of senior advisors to continue to bring in clients and grow the firm further!

The Certified Financial Planner (CFP) certification is the dominant financial planning designation across the financial services industry, providing a valuable signal for clients seeking competent and credible professional financial advice. CFP certification was established in 1973 as a voluntary program that financial advisors could pursue to demonstrate their commitment to professional development and, over the years, CFP Board further standardized the qualifications and ethical standards required to obtain the marks, ensuring that all certificants possess an increasingly comprehensive understanding of financial planning.

As the financial services industry has steadily grown more advice-centric, so has the share of advisors who have obtained their CFP marks. Indeed, the share of financial advisors who are CFP professionals has increased from 1 in 10 25 years ago to 1 in 3 today.

Still, despite this growth, about 2/3 of financial advisors are not CFP professionals. This means that, for most advisors, the decision to obtain this designation remains an open one. A crucial factor in an advisor's decision to study for the CFP exam and enroll in the requisite education courses (which often requires sacrificing evenings and weekends for more than a year, along with many thousands of dollars to pay for tuition) is whether doing so will pay dividends for their career over years to come. Or stated more simply, for many, there is a question of whether the financial benefit of obtaining the CFP marks will be worth their efforts.

The (Positive) Income And Productivity Gaps For CFP Professionals

In theory, putting in the time and energy to earn the CFP marks should be reflected by a higher annual income, whether from working with clients willing to pay CFP professionals higher fees, having the expertise to service a broader range of clients, or simply being better able to get an advisor job (and command raises). Simply put, one of the most straightforward reflections of the 'Return On Investment' of completing the education requirement to earn the CFP marks is whether CFP professionals actually earn more.

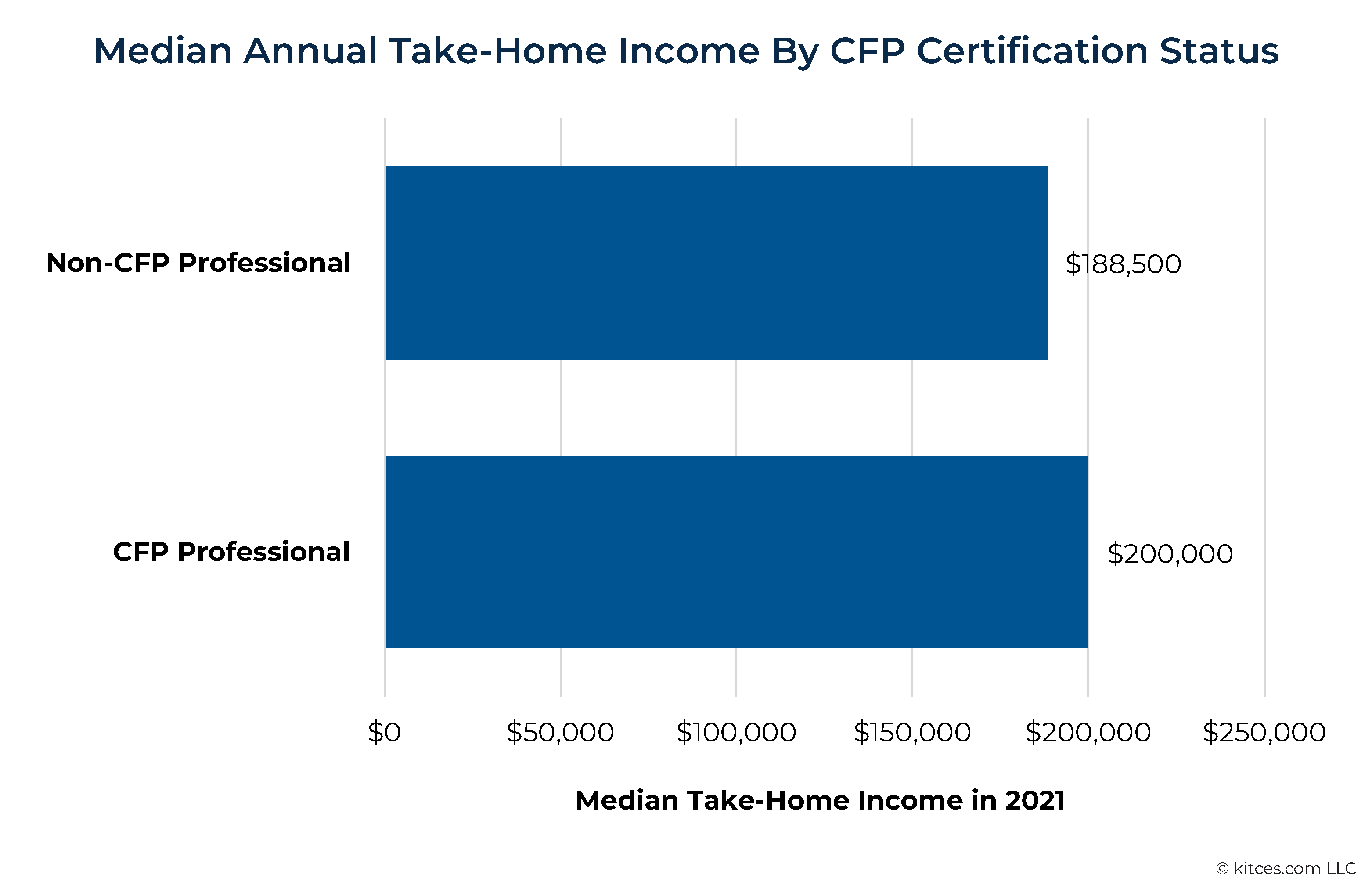

According to the results of our 2022 Kitces Research on "How Financial Planners Actually Do Financial Planning", which evaluated the median annual take-home income between advisors with and without the CFP marks, this really is the case; the typical non-CFP professional advisor took home $188,500, compared to $200,000 for CFP professionals. This means that the typical CFP professional earns $11,500 more each year, nearly twice the initial cost of earning the CFP marks (which typically runs around $6,000 to complete the education requirement for CFP certification, plus a few thousand dollars more for those who choose to take a CFP exam review program as well).

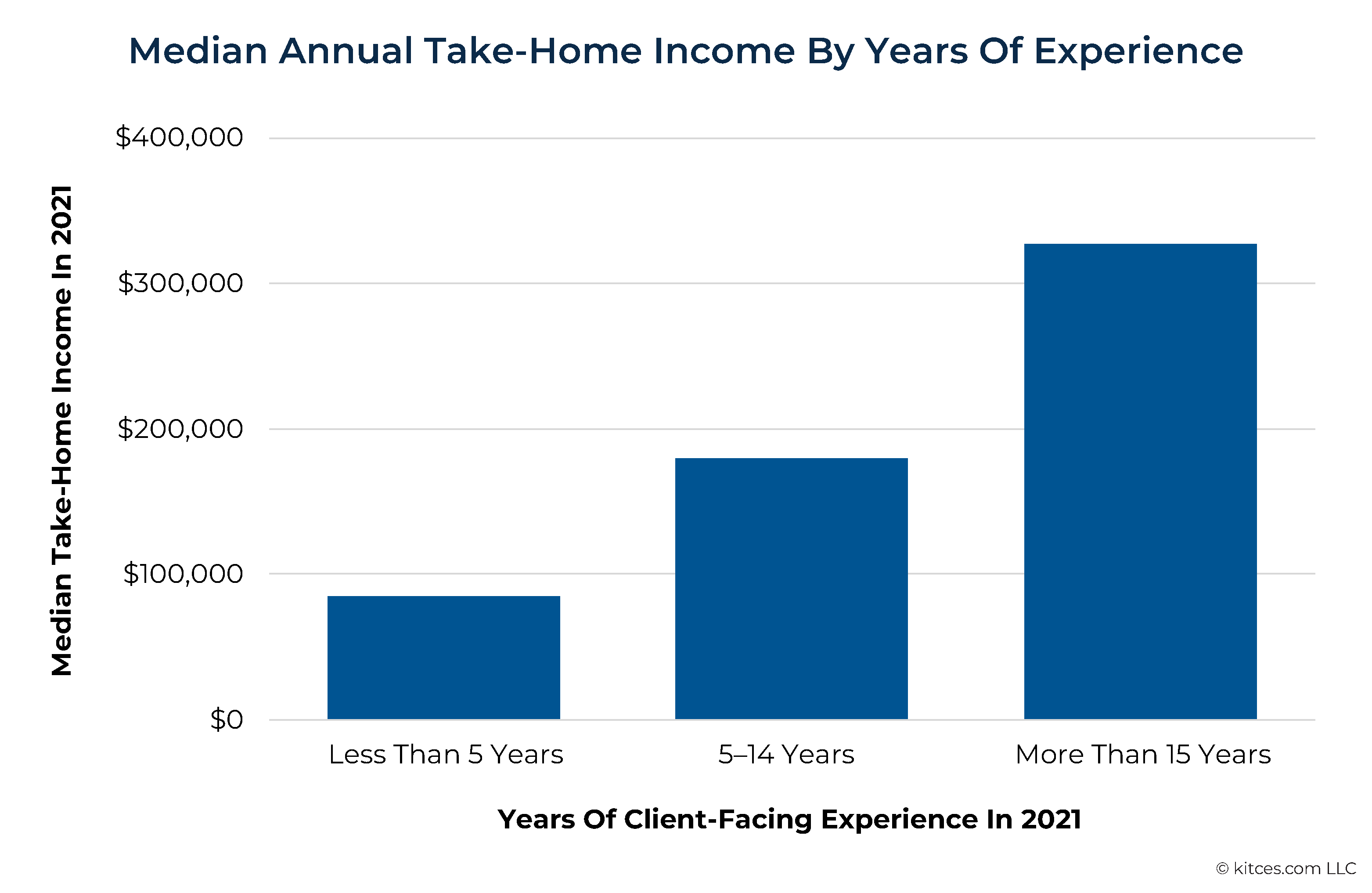

Of course, this income gap could be explained by something other than CFP status. For example, take-home pay itself is highly correlated with advisors’ years of experience for both CFP and non-CFP professionals – being lower in the early years of their careers and higher in the later years, as shown in the figure below.

Since more experienced advisors have higher incomes, one possible explanation for the income gap between CFP and non-CFP professionals might be that the typical CFP professional has more experience. However, across our research sample, the opposite appears to be true. The typical CFP professional actually has 3 fewer years of financial services industry experience (17 versus 20) and 1 fewer year of client-facing experience (12 versus 13) than the typical non-CFP professional. These differences in experience are likely attributable to new entrants to the industry facing more pressure than earlier generations of advisors to obtain the CFP designation (and other designations). Therefore, the income gap between CFP and non-CFP professionals does not appear to be attributable to the former group having more experience, because, in fact, they actually tend to have less!

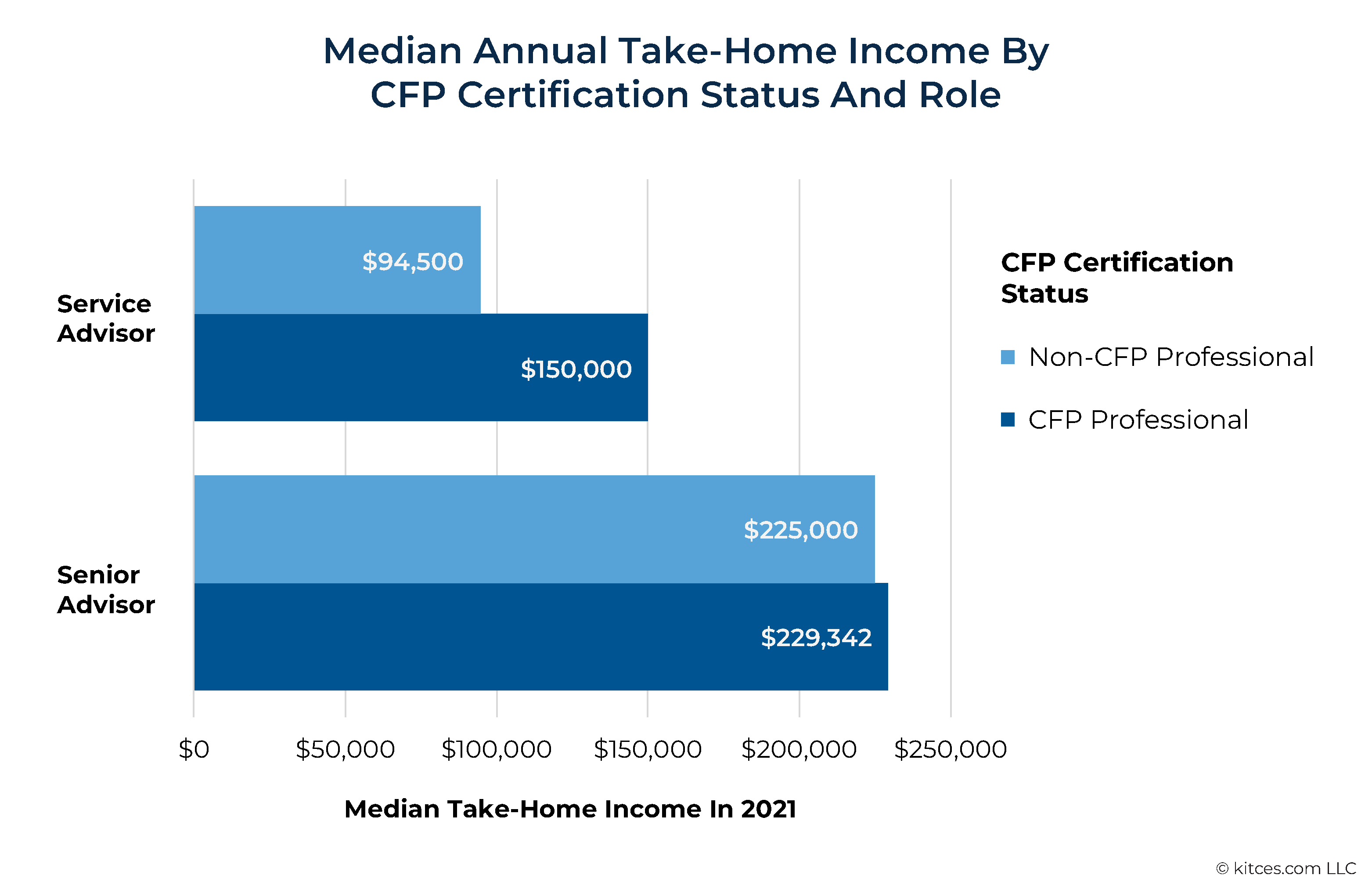

While the figures discussed so far suggest a modest income gap between CFP professionals and non-CFP professionals, further segmenting the data reveals that the size of this income gap varies dramatically based on advisors’ roles.

That is, differences in take-home income between advisors with and without the CFP marks vary markedly depending on whether one looks at senior advisors – responsible for managing the most valued client relationships, mentoring other advisors, and focusing on business development – or service advisors, who primarily focus relationship management and retention of existing clients (but do not have substantive business development expectations). These differences are displayed in the figure below.

While senior advisors consistently earn more than service advisors (given the significant economic rewards that come to those who can successfully do business development to bring in new revenue), the income gap between CFP and non-CFP professionals is dramatically larger for service advisors than for senior advisors. The typical service advisor without the CFP marks takes home $94,500/year whereas those with CFP certification earn $150,000, a difference of $55,500, despite the fact that the typical service advisor who is a CFP certificant has fewer years of client-facing experience (6 years for service advisors with the CFP marks, versus 8 years for those without the marks)!

Conversely, the typical senior advisor without CFP certification takes home $225,000 compared to $229,342 for those with the CFP certification – a difference of only $4,342. Simply put, CFP certification status matters a lot for the income of service advisors, but much less for senior advisors.

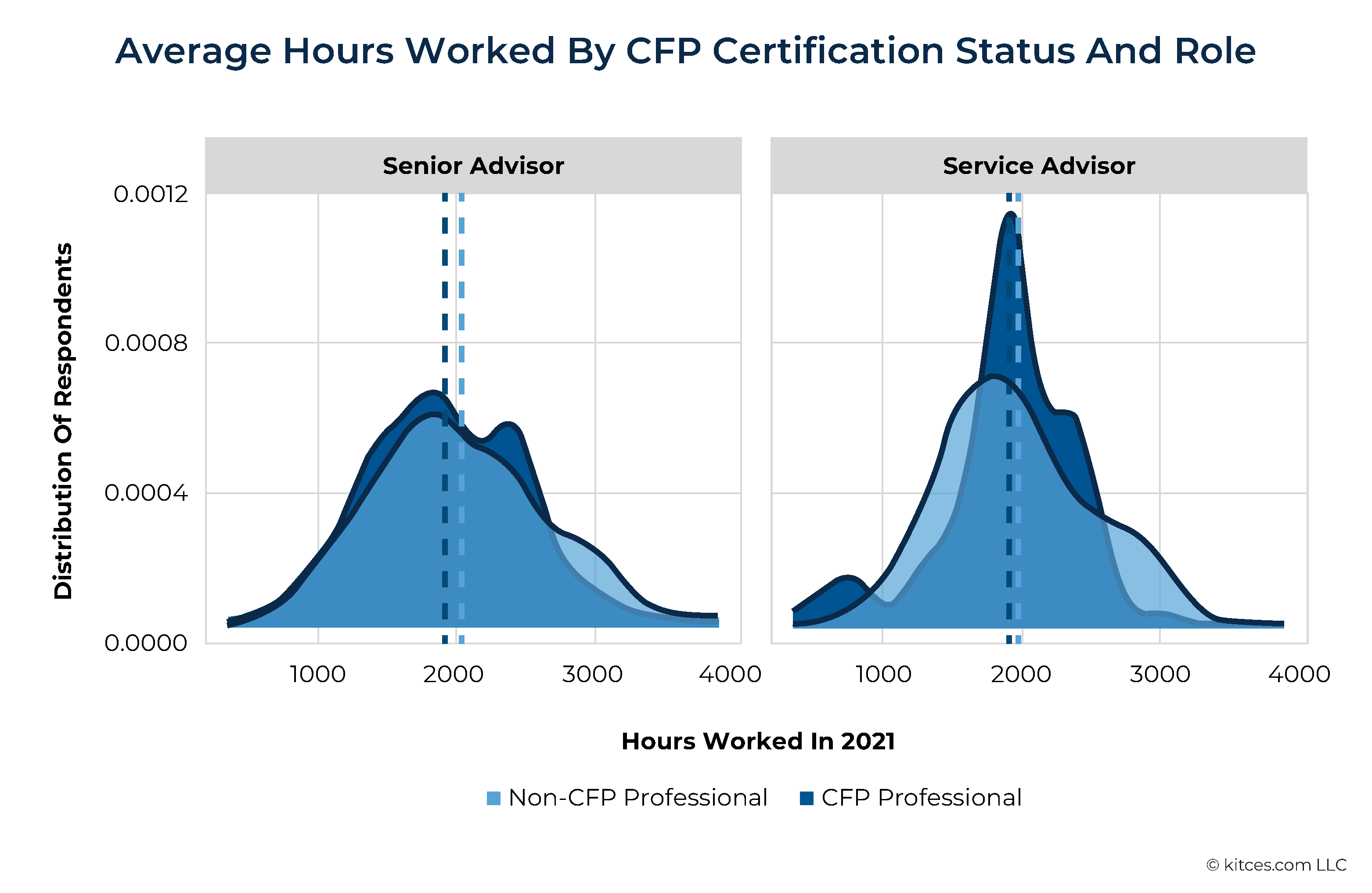

Of course, income growth cannot come at all costs. If CFP professionals make more money than non-CFP professionals merely by grinding out longer hours, they would risk simply burning out. However, it turns out that for both senior advisors and service advisors, CFP certificants work fewer hours than those in the same role without the CFP marks – not more.

Among senior advisors, those who are CFP professionals work an average of 1,919 hours/year, compared to 2,031 for non-CFP professionals – a difference of 112 hours, roughly akin to nearly 3 weeks of annual vacation and time off, assuming a 40-hour work week! For service advisors, the typical CFP professional works 1,909 hours/year while the typical non-CFP professional works 1,970 hours, a difference of 61 hours (equivalent to 1.5 weeks of time off).

The key takeaway from this comparison of working hours is simply that the higher take-home pay earned by CFP certificants is not an artifact of grueling work schedules. Instead, CFP professionals appear to be more productive – that is, they earn more income per hour worked, while enjoying more consistent time off.

In turn, when looking at productivity more directly – i.e., take-home income per hour worked – based on CFP certification status and role, as expected, senior advisors earn more per hour than service advisors regardless of whether they've attained the CFP marks. However, within these senior and service advisor roles, CFP professionals are more productive, especially for the latter group. The typical service advisor without CFP certification earns $48.83/hour, compared to $86.30 for service advisors with the CFP marks – a difference of $37.47, or a whopping 77% boost in income per hour! The typical senior advisor without CFP certification earns $112.47/hour, compared to $120.00 for CFP professionals, a far more modest difference of only $7.53 (or a 6.7% boost in income per hour).

In summary, merely observing that CFP professionals earn more than non-CFP professionals hides the fact that the size of this income gap is much larger for service advisors than for senior advisors. For service advisors in particular, the late nights of studying really pay off – amounting to over $50,000/year in additional take-home income! And rather than being the result of working unsustainable hours, this gap in income is because CFP professionals – especially service advisors – are more productive, earning more per hour worked. Or stated more simply, when advisors earn the CFP marks to enhance their knowledge, a "CFP Productivity Gap" emerges because CFP professionals really can subsequently charge more for their expertise and take more time off!

Supply- Vs Demand-Side Explanations For The "CFP Productivity Gap"

Our Kitces Research on Advisor Productivity shows that the CFP marks boost advisor productivity (i.e., income per hours worked), but that the effect is significantly greater for service advisors (who don't have significant business development obligations) than for senior advisors (where the effect is more muted). This raises important questions: why is there a CFP Productivity Gap – and why is this gap larger for service advisors than for senior advisors? Answers can be categorized into 2 camps: supply-side explanations and demand-side explanations.

Supply-side explanations focus on the characteristics and behaviors of the advisors themselves, such as their skill sets and how they allocate their time (e.g., CFP professionals tend to be more productive with their time than non-CFP professionals). Demand-side explanations, on the other hand, are based on clients' preferences, such as those with more investable assets preferring to work with CFP professionals (and/or firms that work with such clientele having a preference to hire CFP professionals to service them).

Of course, these explanations are deeply intertwined; wealthier clients, often with more complex needs, are likely to prefer CFP professionals who typically come with deeper skill sets that enable them to be more productive in delivering client value. Still, these categories offer a useful framework for thinking about different ways in which CFP certification may boost advisor productivity.

Do CFP Professionals' Skill Sets And Time Allocation Boost Productivity?

From the supply-side perspective, a potential reason that CFP professionals, and those who are service advisors in particular, are more productive is simply that they're 'better' at key aspects of their job as financial planners. One way we can measure this is by looking at whether CFP professionals offer more extensive financial planning services than non-CFP professionals; another is by examining whether they dedicate more time to key revenue-generating activities.

CFP Professionals Offer More Extensive Financial Planning Services

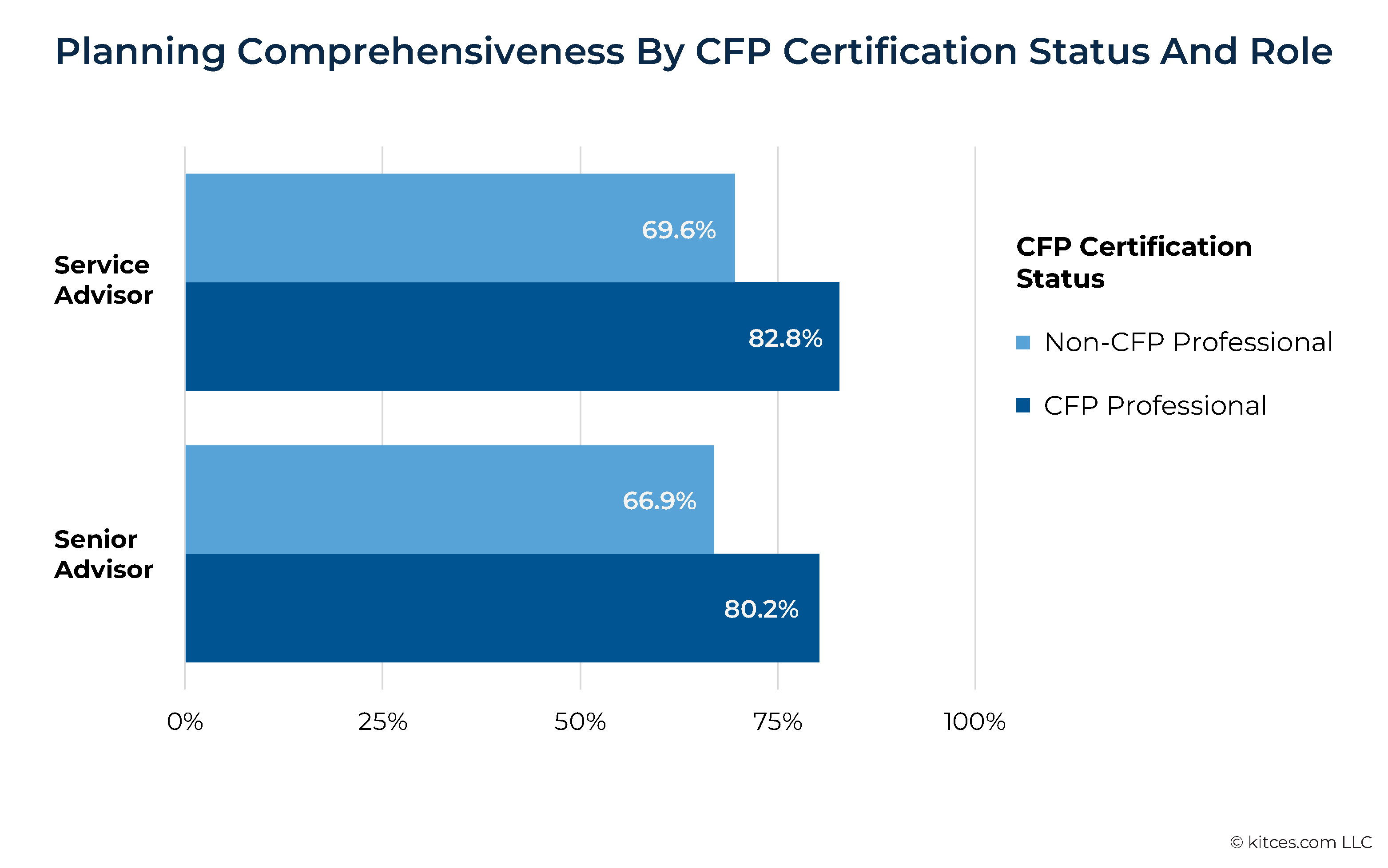

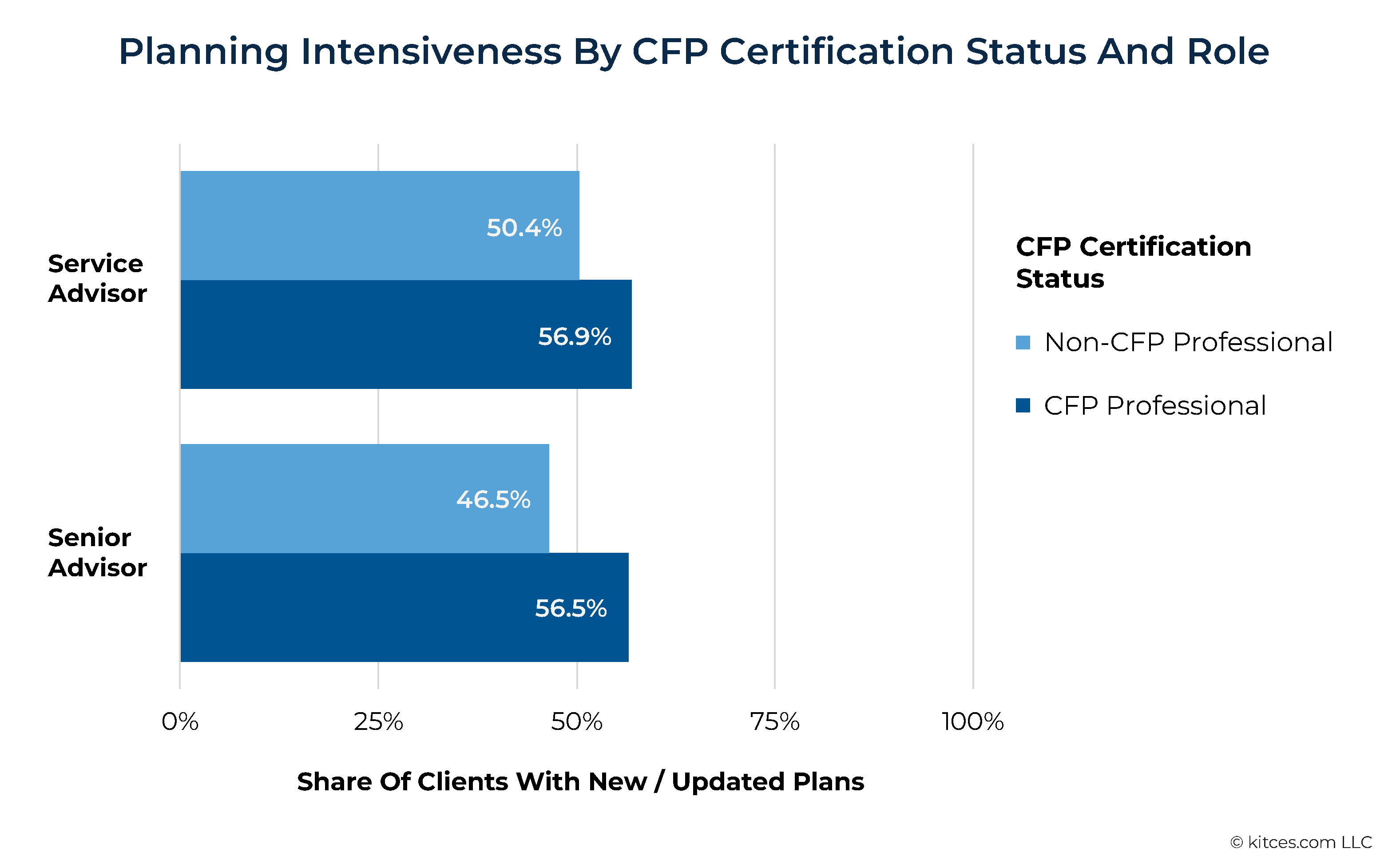

One way we can explore whether the CFP Productivity Gap is attributable to CFP certificants offering more extensive financial planning services is by examining rates of planning comprehensiveness – defined by Kitces Research as offering financial plans that cover 10 or more financial planning domains (e.g., estate planning, college planning, retirement income planning, etc.). Another way is by examining the proportion of advisors' clients who have received new or updated plans within the last 12 months – a metric Kitces Research refers to as planning intensiveness.

Together, planning comprehensiveness and planning intensiveness capture the centrality of planning in advisors' practices: the first indicates the breadth of plans that are created, while the latter indicates the frequency with which these plans are created or modified.

The data from our Kitces Research on Advisor Productivity shows that CFP professionals are more likely to offer comprehensive financial plans than non-CFP professionals regardless of advisors' roles. Approximately 80% of both senior and service advisors with the CFP marks offer comprehensive financial plans, compared to under 70% of those without the CFP marks.

Turning to planning intensiveness, a similar picture emerges. About 57% of clients serviced by CFP professionals have new or updated financial plans in the past 12 months, compared to about half of the clients serviced by non-CFP professionals, and these results are again remarkably consistent regardless of advisors' roles.

Taken together, the fact that more frequent and comprehensive planning is central to the roles of CFP professionals more than for non-CFP professionals offers one supply-side explanation of the CFP Productivity Gap. Simply put, CFP professionals develop more comprehensive plans that they update more frequently and get compensated for doing so.

However, these findings alone do not explain why the CFP Productivity Gap is larger for service advisors than senior advisors – a finding that requires further exploration.

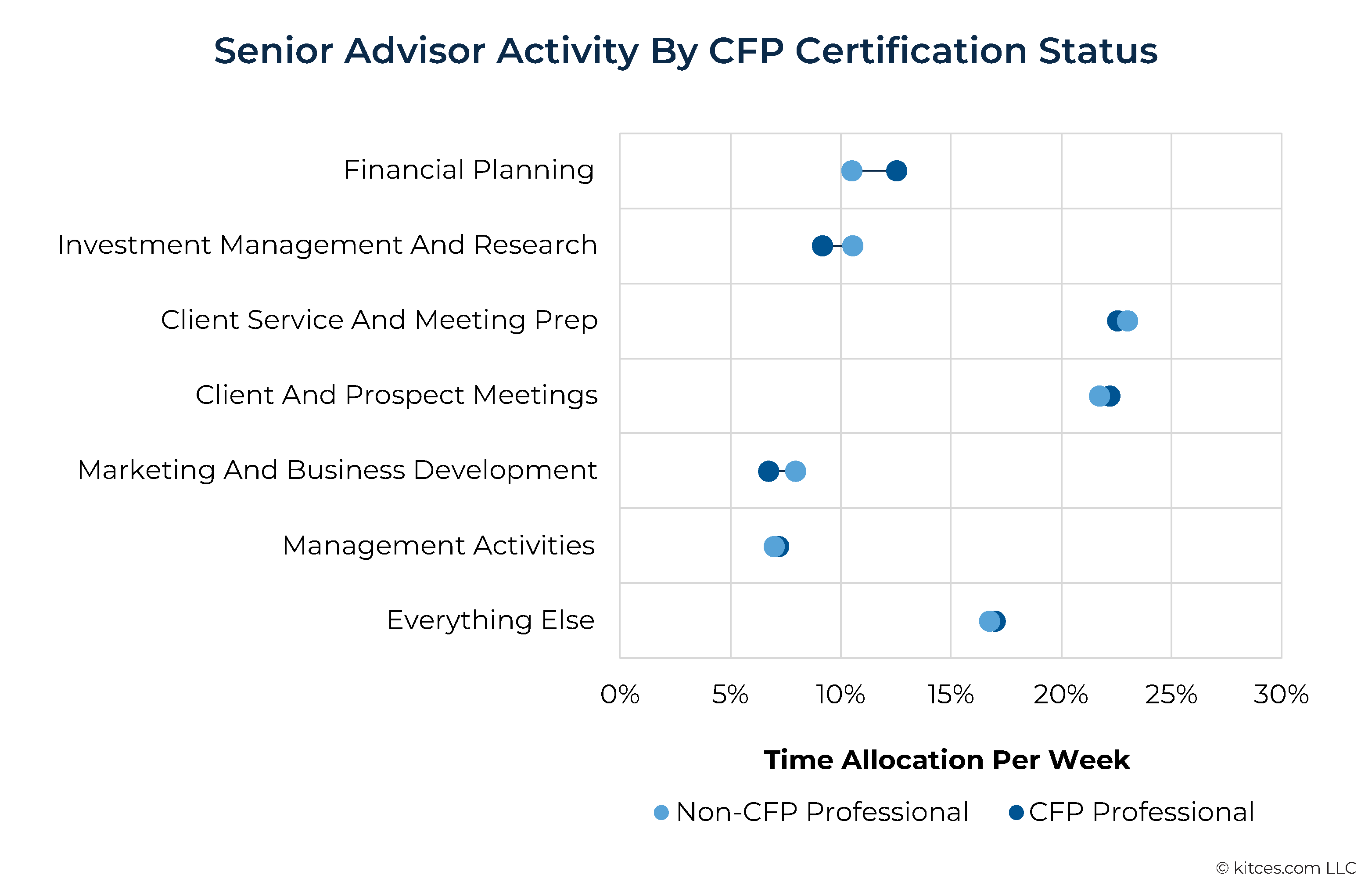

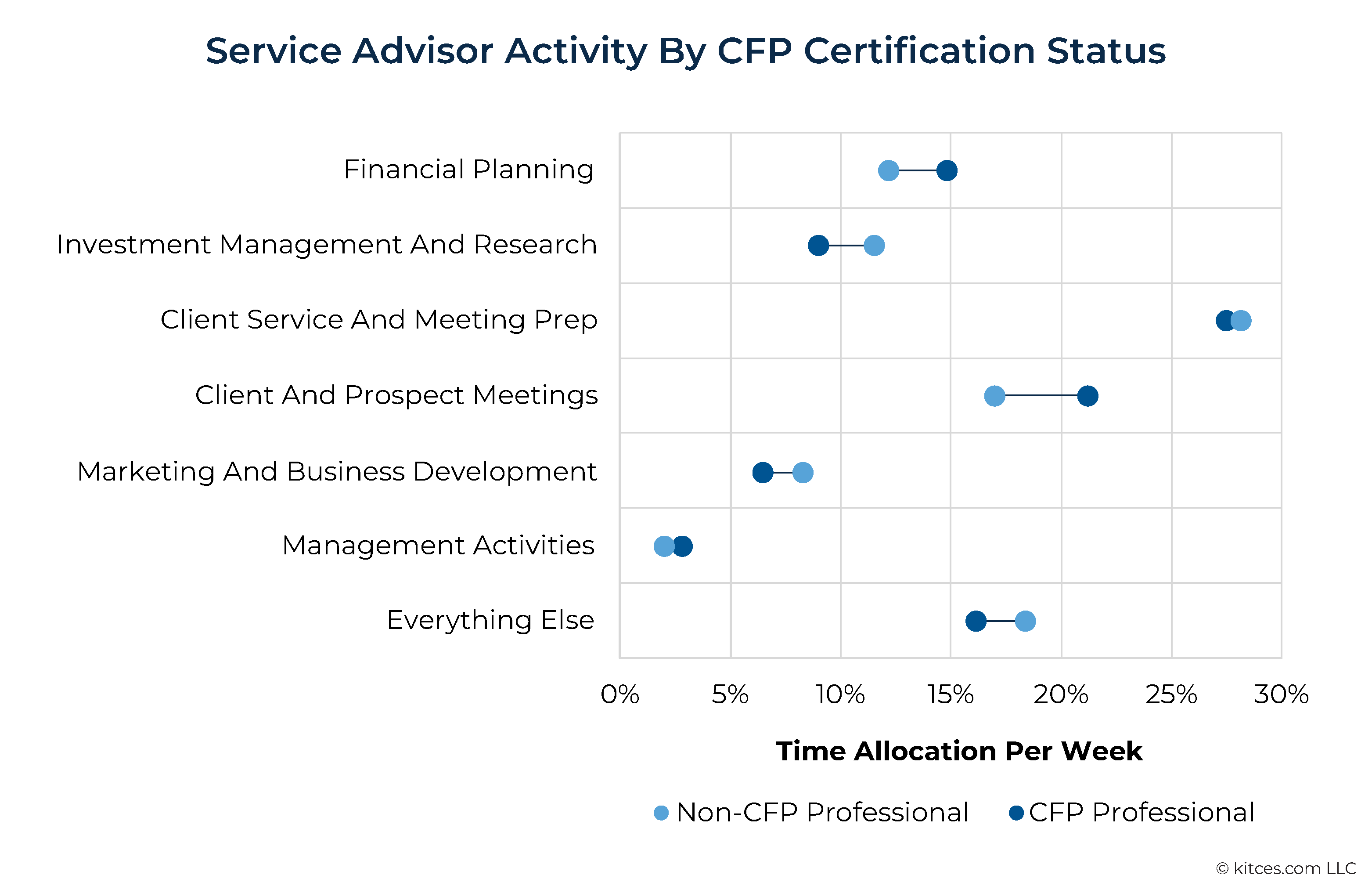

CFP Professionals Spend More Time Meeting with Clients and Actually Doing Financial Planning

Financial planners have many tasks to cover throughout their workdays, from doing planning work for existing clients to getting new clients, handling administrative tasks, managing compliance, seeking professional development, and more. Accordingly, one potential explanation for why CFP professionals are more productive is that they're more consistent at engaging in key revenue-generating activities such as meeting with clients and financial planning (and less time in other tasks less associated with revenue generation).

To explore this, we examine the hours financial advisors dedicate per week to different areas, based on CFP certification status and role. The 7 domains we included in our study are as follows:

- Financial planning;

- Investment management and research;

- Client service and meeting preparation;

- Client and prospect meetings;

- Marketing and business development;

- Management activities; and

- Everything else (e.g., administrative work, compliance, and professional development, among other activities).

For senior advisors, there is little difference in the time CFP professionals dedicate to these 7 domains compared to non-CFP professionals. Both dedicate about 23% of their time to client service and meeting preparation, 7% to management activities, and 17% to "everything else." Senior advisors with the CFP marks do dedicate slightly more time to financial planning (12.6% versus 10.6%), which is partially compensated for by working fewer hours on investment management (11% versus 9.5%) as well as marketing and business development (8.4% versus 7.2%). However, for senior advisors, the key takeaway is that, for the most part, CFP and non-CFP professionals allocate their time similarly across our 7 domains.

For service advisors, however, larger disparities emerge based on CFP certification status. Service advisors with the CFP marks spend more time on financial planning (15.3% versus 12.7%) and meeting with clients and prospectus (21.3% versus 17.1%) – each of which are key revenue-generating activities. They dedicate fewer hours to investment management (9.1% versus 12%), marketing and business development (6.7% versus 8.5%), and "everything else" (16.4% versus 18.6%). Both groups of service advisors work about 28% of their time on client service and 3% of their time on management activities.

In the aggregate, these differences are quite material. When looking at overall hours worked, service advisors with the CFP marks spend 2 additional hours per week in client meetings. 2 hour-long meetings per week adds up to more than 100 additional client meetings per year, which can enable a substantially higher amount of client revenue served (either by working with more clients in more meetings or more sophisticated clients who pay more and demand more service).

Allocation of time, then, offers a possible explanation for why the CFP Productivity Gap is larger for service advisors than for senior advisors. Namely, among service advisors, CFP professionals dedicate more hours per week to key revenue-generating activities – meeting with clients and generating financial plans – than non-CFP professionals, while spending less time on tasks such as marketing, investment management and research, and other miscellaneous tasks.

High Net-Worth Clients Who Pay Higher Fees Prefer CFP Professionals Over Non-CFP Professionals

As the preceding data from our Kitces Research on Advisor Productivity has shown, CFP professionals are offering more extensive financial planning services than non-CFP professionals (as measured by both planning breadth and intensiveness) and, among service advisers, those with their CFP marks are spending more time on key revenue-generating activities (i.e., generating financial plans and meeting with clients and prospects).

We turn now to investigating demand-side explanations – i.e., explanations rooted in the preferences of clients – for the CFP Productivity Gap. Namely, we explore the possibility that CFP professionals are earning more at least in part because of their ability to attract more affluent and complex clients who are willing to pay higher fees in the first place.

One of the most straightforward ways to examine this is simply to evaluate whether CFP professionals' clients have more investable assets than the clients of non-CFP professionals (as a proxy for CFP professionals' ability to attract more affluent and complex clients) and, crucially, whether this gap in clients' investable assets is larger among service advisors than senior advisors.

Nerd Note:

Kitces Research captures variables such as revenue, client investable assets, and the number of clients at the service-team level. One challenge when displaying typical levels of these variables based on a respondents CFP certification status and role is that, for teams with multiple senior and/or service advisors, segmenting team-level variables would be based on features of the particular team member who happened to complete our survey. Which means that they may not be representative of the team as a whole.

In addition, service advisors are more likely to work in larger teams while many senior advisors in our sample are solo advisors. This risks making comparisons between senior and service advisors that may be distorted by large differences in team size.

To address these concerns, the following analyses restricted samples to those with respondents on service teams containing 1 senior advisor and 1 service advisor. This was not required in earlier analyses because all variables were captured at the individual level.

As the results reflected in the graphic below show, more affluent clients do indeed appear to have a strong preference for CFP professionals over non-CFP professionals! Amongst senior advisors, those with their CFP marks had a median client household of $1,000,000, compared to 'only' $650,000 amongst non-CFP certificants, reflecting a whopping 54% increase in typical client affluence of CFP professional senior advisors.

When it comes to CFP professional service advisors, though, the difference is even more dramatic, with service advisors who have the CFP marks averaging $1,000,000 AUM households, while service advisors without the CFP marks average only $250,000 clients. Given that CFP professionals who are service advisors have the same median AUM client as those who are senior advisors while non-CFP professionals who are service advisors have clients that are half the size of those who are senior advisors, this further suggests that senior advisors who have their CFP marks might be more effectively able to transition their 'average' client to a service advisor to create capacity for themselves, while senior advisors without the CFP marks may be primarily shifting only their smallest clients to their (non-CFP professional) service advisors.

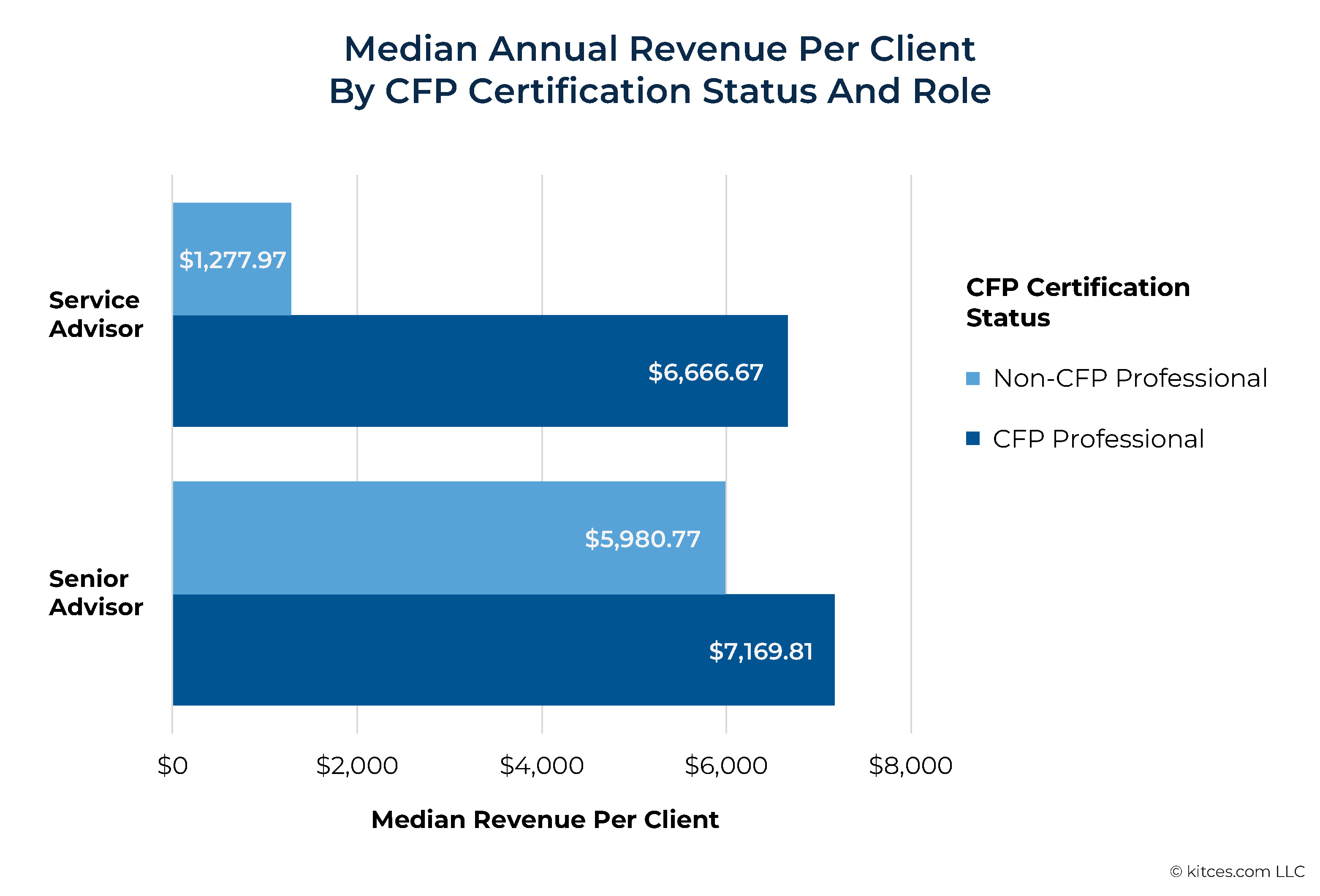

CFP Professionals’ Wealthier Clients Pay Higher Fees

If differences in investable assets between CFP professionals and non-CFP professionals explain the CFP Productivity Gap, it would be because CFP professionals can generate more revenue per client, earning more for each hour they work. And this is precisely what the data suggests. Among teams consisting of 1 service advisor and 1 senior advisor, the typical team with a non-CFP professional service advisor generates $1,278 in revenue per client, compared to $6,667 for teams with a service advisor who has their CFP certification – a difference of $5,389. For these same teams, we see smaller differences in revenue-per-client based on the CFP certification status of the senior advisor.

Teams with a non-CFP professional senior advisor typically generate $5,981 in revenue per client while teams with a senior advisor with the CFP marks typically generate $7,170 – a difference of $1,189. Which implies that the key boost in productivity is not only due to CFP professional senior advisors who can attract slightly higher revenue clients than those who don't have their CFP marks, but that the CFP professional senior advisors are able to delegate such clients to service advisors (who also have their CFP marks) to create team leverage (whereas non-CFP professional service advisors again appear to take on only the smallest of clients, potentially leading to a 'capacity bottleneck' amongst senior advisors).

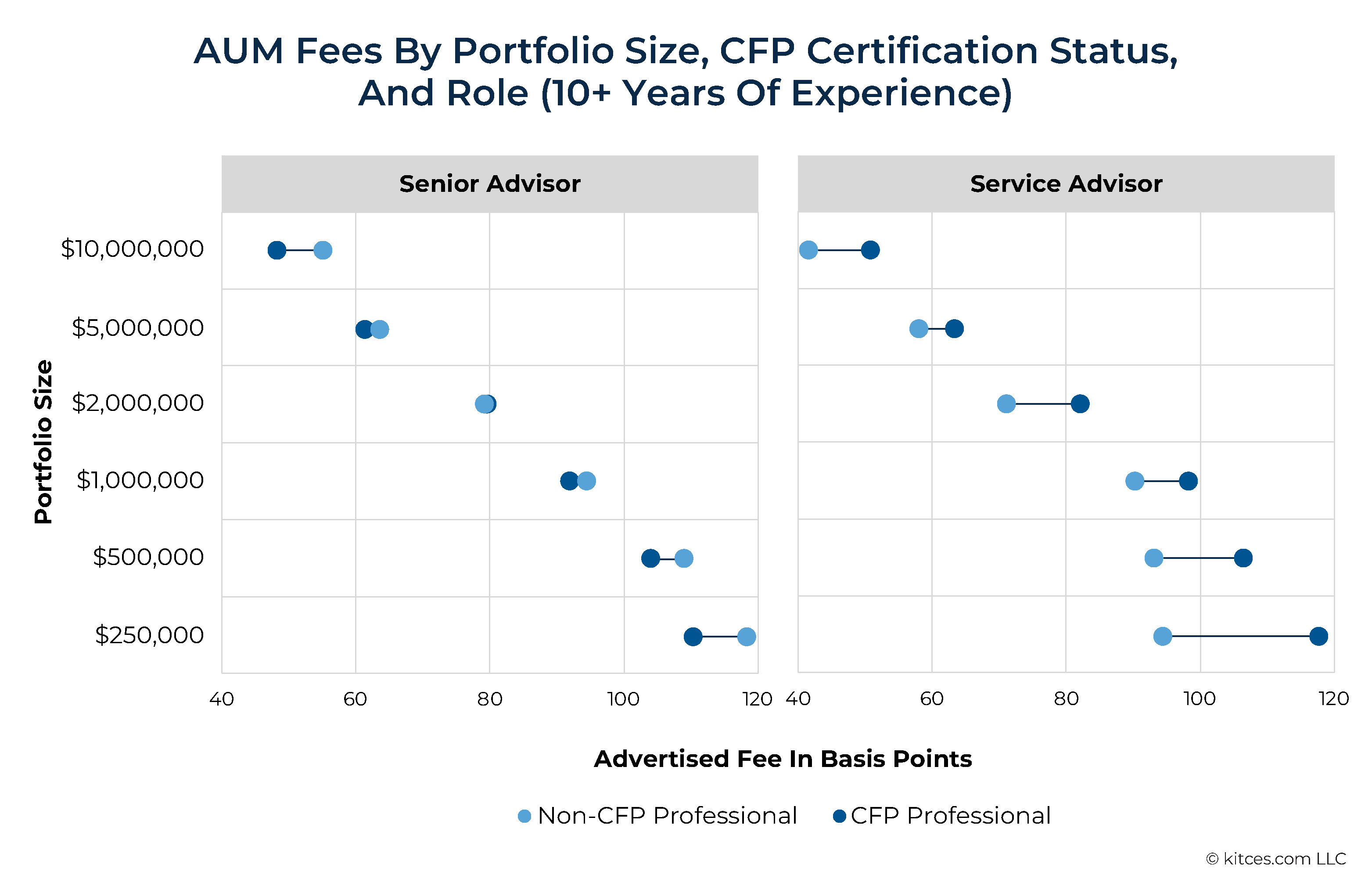

This, in turn, raises an interesting follow-up question: Do CFP professionals generate more revenue per client merely because they have wealthier clients (i.e., clients with a larger portfolio on which AUM fees are based) or because they also charge higher fee rates in the first place? Indeed, it is mathematically possible for CFP professionals to have lower fee schedules than non-CFP professionals and still earn more revenue per client because they bring home a smaller slice of a much larger pie. Another possibility, however, is that CFP professionals charge more than non-CFP professionals and outearn them in part because they can command higher fees from the same client (e.g., because they offer more services to that client to merit the higher fees).

We explore this by looking at reported AUM fees for various portfolio sizes among firms that generate at least some revenue from AUM fees. Further, because CFP professionals tend to average fewer years of industry experience than non-CFP professionals (as newer advisors are more likely to have their CFP certification because they are growing their practice at a time when the industry places greater emphasis on financial planning and greater value on professionals with CFP certification), we control for this by restricting our sample to advisors with 10 or more years of industry experience.

Among teams consisting of 1 service advisor and 1 senior advisor, there is little difference in advertised fees based on the CFP certification status of the senior advisor other than for the smallest ($250,000) and largest (more than $10,000,000) portfolios. Teams in which the senior advisor has CFP certification charge lower fees than teams whose senior advisor does not have their CFP marks, possibly because these advisors are more likely to be compensated in other ways such as separate financial planning fees and/or by being able to better attract clients with more investable assets.

Across portfolio sizes, AUM fees only vary an average of 4.1 basis points based on the CFP status of senior advisors. By contrast, though, AUM fees vary substantially based on the CFP certification status of service advisors – with this difference amounting to 12.6 basis points.

The implication of these results is that, again, CFP professional service advisors appear more fully capable of taking on the 'typical' client of the senior advisor, while non-CFP professional service advisors not only take on smaller clients but also appear to discount their fees more aggressively to earn or retain those clients.

Taken together, the key point is that teams with service advisors who have their CFP marks earn more revenue per client than teams with service advisors who don't have the CFP marks, not only because they have wealthier clients but also because they are able to command higher fees for their expertise.

The CFP Productivity Gap Widens Over Time – Especially For Service Providers

The fact that CFP professionals are able to attract wealthier clients (who are willing to pay higher fees) suggests that this group has better earnings trajectories over the course of their careers than non-CFP professionals. This is important because, as advisors often tell their clients, consistent average annual compound growth over long periods of time can lead to substantial increases in portfolio values. At a given rate of compound growth, a larger initial portfolio will result in a greater absolute increase in portfolio size over a fixed period.

Which means that when CFP advisors attract more affluent clients with larger portfolios in the first place, as their clients' portfolios grow, so does the absolute size of the asset base from which firms can generate revenue. For advisors charging asset management fees (or recurring commissions based on the size of assets, such as 12b-1 fees), wealthier clients translate into more revenue both now and in the future. Hence, advisors with CFP certification should experience greater income growth over their careers than those without CFP certification.

Further, there is good reason to expect that the gap in income growth between CFP professionals and non-CFP professionals will be larger for service advisors than for senior advisors. This is because while service advisors have much less consistent compensation structures, compensation for senior advisors (whether they have their CFP marks or not) almost universally are based on revenue-based models; the more revenue they generate, the more they earn. While senior advisors who are CFP professionals generally have wealthier clients than those who are non-CFP professionals, the compensation models and income growth trajectories are fundamentally the same: As client headcount increases and portfolios (hopefully) experience steady compound growth, advisors’ income follows suit. The primary limiting factor is typically not the senior advisors’ personal productivity, but their ability to hire and expand their teams and to sustain their business development efforts to keep growing the client base itself.

By contrast, service advisors tend to have an array of different compensation structures. Some are partially compensated by the revenue that they help generate but tend to have lower payouts than senior advisors because they typically do not participate in the profitability of the overall business; they're 'just' paid to service their own client base. Others are entirely compensated through a salary alone for the clients they serve. And while the salaries that service advisors earn are significantly shaped by the service team's revenue (with high-earning practices often able to afford 6-figure salaries), over the long term, receiving a share of a growing revenue base is almost certain to yield more income based on business development skills, while service advisors that are more heavily salary based have financial outcomes more directly dictated by their own productivity and financial planning skill set.

Accordingly, the more time CFP professional service advisors are spending on revenue-generating activities – such as meeting with clients and financial planning – as was shown earlier, the more their income trajectory should outpace non-CFP professional service advisors. And this is precisely what the data suggests when the productivity trajectories of CFP versus non-CFP professionals – for both service advisors and senior advisors – are mapped out over time.

For senior advisors, there is little difference in productivity – as measured by take-home pay per hour worked – between those with CFP marks and those without during their first 7 years in the financial services industry; both groups generate about $48/hour of take-home income. However, the irony is that because of the apparently rising demand for service advisors with CFP certification – who increasingly have access to more stable salaried jobs out of the gate, without needing to build their own client base from scratch – service advisors with their CFP marks actually out-earn senior advisors, both with and without CFP certification (taking home an average of $56.80/hour, which would equate to an annual salary of more than $100,000 with ~2,000 working hours in a year), in addition to beating out service advisors without CFP certification (who earned only $48.50/hour).

On the other hand, part of the reason that senior advisors (with and without their CFP marks) are less productive in the early years is simply that they haven't built their client bases yet… and, as a result, we unsurprisingly find that by the mid-career stage (firms that have been in business between 8–19 years in the business), senior advisors are catching up to service advisors with their CFP marks.

However, service advisors who are CFP professionals themselves also experience a huge lift in productivity as they build their own experience – rising to $98.40/hour of earnings – such that CFP service advisors still stay slightly ahead of non-CFP senior advisors (who earn only $94/hour). And even senior advisors with the CFP marks only slightly surpass service advisors who are also CFP professionals, growing their average take-home earnings to $104/hour. (Given that there are approximately 2,000 working hours in a year, these are roughly akin to $200,000/year in advisor earnings.)

Service advisors without their CFP marks begin to substantially lag in earning potential by their mid-career stages when they are neither building their own client base (as a senior advisor) nor deepening their expertise (by earning CFP certification), taking home only $55.60/hour during this career stage (and not much higher than the $48/hour they were earning in their initial career stage!).

By later career stages, the cumulative investment that senior advisors make into building their own practices really does begin to show up; amongst those with 20 or more years of experience in the financial services industry, both groups (senior advisors with and without CFP certification) begin to substantially out-earn CFP professional service advisors, with CFP professional senior advisors taking home $159/hour, compared to non-CFP professionals who take home $156/hour, and CFP professional service advisors who earn 'just' $125/hour at the same stage.

Notably, because career success at this stage is almost entirely driven by cumulative growth of the senior advisor's client base – which has a natural self-selection bias for those most able to bring in their own clients – there doesn't appear to be a substantive gap between senior advisors who are CFP and non-CFP certificants in the late career stage (as again, the CFP marks don't appear to contribute as much to the particular business development skill set that defines senior advisor success and longevity).

Nonetheless, because senior advisors naturally face capacity constraints as their client bases grow – driving a need to hire service advisors, for which the data is increasingly showing a preference for service provided by CFP professionals – the results do show that for service advisors with 20 or more years of experience, the productivity gap and income benefits of CFP certification are most evident! As noted above, service advisors with CFP certification are taking home an average of $125/hour, a whopping 64% more than service advisors who are not CFP certificants, who take home an average of only $76.40/hour at this career stage; notably, this nearly $50/hour difference, writ large across nearly 2,000 working hours in a year, amounts to a $100,000+ take-home income difference between service advisors who have their CFP marks versus those who don't!

Advisory Firms And Their (Service) Advisors Grow By Investing Into Their CFP Certification

Ultimately, our Kitces Research on Advisor Productivity shows CFP professionals take home more per hour than non-CFP professionals, with this gap being substantially larger for service advisors than for senior advisors ($48.33/hour versus $86.30/hour, respectively). This disparity in earnings per hour – what we have dubbed the CFP Productivity Gap – appears to be driven by explanations stemming from both the skills that CFP professionals develop and deliver (supply-side), and the preferences of clients – especially more affluent clients – when selecting an advisor to work with (demand-side).

Taken together, then, it appears that service advisors really benefit from pursuing the CFP marks, and firms are likely to benefit from supporting them by expanding their teams of service advisors who can take on and support the firm's most high-dollar clientele (in turn freeing up capacity of senior advisors to continue to bring in clients and grow the firm further!).

Career Service Advisors Unlock Significantly More Earning Potential With CFP Certification

While income growth among senior advisors is robust regardless of CFP certification status (there is a modest CFP Productivity Gap for senior advisors with more than 7 years of experience), as outcomes are driven more by business development capabilities than delivering financial planning services, income growth for service advisors appears to be especially driven by CFP certification, for both the training it provides and the preference of more affluent clients to have a financial advisor with CFP certification.

Notably, this does not necessarily mean that earning CFP certification results in an immediate salary raise or boost in clientele; nonetheless, the results show that service advisors with CFP certification see their earnings lift by $41/hour (amounting to more than $80,000/year in additional income potential) from early career (7 or fewer years of experience) to their mid-career stage (8–19 years of experience), compared to a lift of less than $8/hour for those without CFP certification.

Hence, the CFP marks appear to be a crucial vehicle providing service advisors with continued income growth over time. For which the long-term income potential far exceeds the cost of not just the coursework required to meet the educational requirement for CFP certification but also the supporting CFP exam review program.

Firms Looking To Attract, Retain, And Especially Delegate More Affluent Clients Benefit From Hiring CFP Professionals (Or Helping Its Employees Obtain The CFP Marks Themselves)

One demand-side explanation for the CFP Productivity Gap is that teams with CFP professional service advisors have wealthier clients who are willing to pay higher fees. This fact has a key implication for firms looking to attract and retain affluent clients: hire CFP professionals or help existing employees obtain them. The knowledge obtained through CFP certification can be used to forge a more planning-centric practice, offering more comprehensive financial plans that are updated more frequently – each of which are clear value-adds for high-net-worth households who often have complex planning needs.

The Higher Wages Of Service Advisors With CFP Certification Are Offset By Increased Revenue

Our Kitces Research in Advisor Productivity shows that service advisors with CFP certification typically have significantly more affluent clients who pay substantively higher fees compared with those without the CFP marks ($1,000,000 AUM versus $250,000 AUM median clientele, respectively). Which has profound implications for larger advisory firms looking to move upmarket or scale their financial planning services by freeing up capacity from senior advisors (who need to be able to delegate all their clients, not just their smallest "C" clients, to other advisors on the team).

Nerd Note:

While Kitces Research captures the CFP certification status and income of individual respondents, we also capture revenue at the level of respondents' service teams. Examining differences in service teams' revenue based on CFP certification status of the particular member of the team who happened to complete the survey is problematic because teams vary substantially in their number of advisors, all of whom contribute to firm revenue. Therefore, we restrict our sample to teams containing only 1 service advisor, and contrast levels of revenue based upon their CFP certification status.

Yet, while there appears to be a clear benefit for firms to hire and train CFP professionals, especially in service advisor roles, they must also bear the financial cost of doing so. After all, by definition, service advisors, with their CFP marks, make more than those without CFP certification, and they do so because their firms are paying them more! This raises the question: Does the revenue generated by employing service advisors with CFP certification and/or supporting the firm's existing advisors to get their CFP marks outweigh the costs of employing them at CFP professional salaries (plus the cost of supporting their education itself)?

Our data suggests that the answer is yes.

When a service advisor with CFP certification is the sole service advisor on a service team, they earn a median of $200,000, compared to $109,302 for service advisors without CFP certification, a difference of $90,698. However, teams with a service advisor who is a CFP professional typically generate $500,000 in revenue per full-time advisor, compared to $158,083 for teams with a service advisor without the CFP marks – a difference of $341,917 in revenue per advisor. This means that the typical firm with a single service advisor generates about $350,000 more in gross revenue per advisor, at a cost of 'just' $90,000 more per CFP professional, representing a clear net financial benefit of about $250,000 per advisor!

Ultimately, the data collectively suggest that the CFP marks offer a powerful productivity boost both to service advisors and to the firms that employ them, driven by both the capabilities of CFP professionals delivering financial planning services and the preferences of consumers – especially more affluent consumers who pay more in fees to solve more complex financial problems – to work with a CFP professional in the first place!

Leave a Reply