Executive Summary

Self-worth can be an important component of an individual’s well-being, but people often base their own sense of self-worth on how they compare with others around them. And because finances are often a part of that comparison, the financial situation of the people we interact with on a regular basis can have a significant effect on how we perceive our own self-worth. For financial advisors, this could mean that comparing themselves to their own clients (who tend to have high incomes and net worth) can have negative effects on how they view their self-worth, especially when they believe that their level of success or income does not measure up to that of their clients.

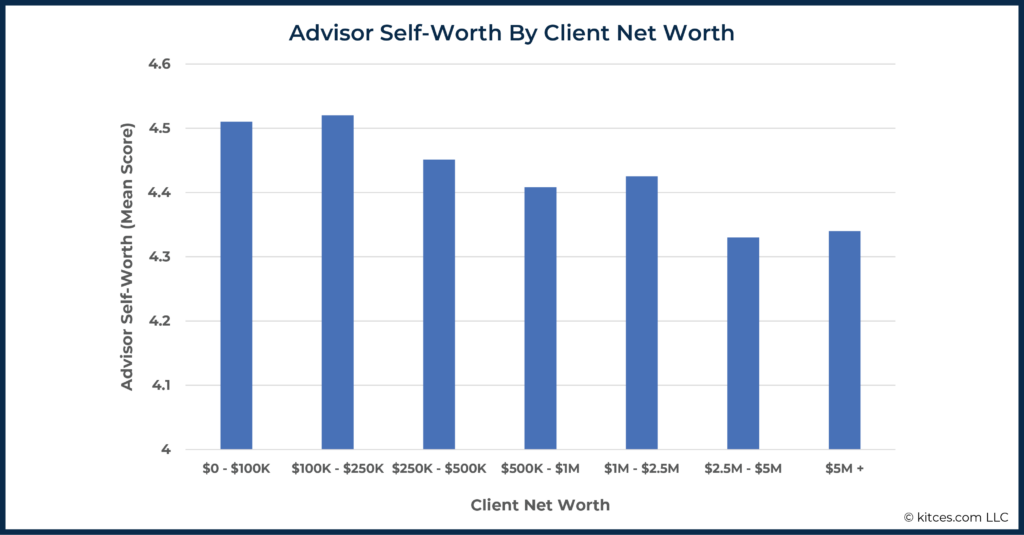

According to Kitces Research on Advisor Wellbeing, advisors on average do tend to have a high sense of self-worth. But despite being high overall, there is a small but clear pattern in which advisors’ self-worth declines as the net worth of their clients grow, with a steep drop-off coming as clients surpass $2.5M in net worth. Which suggests that being around high-net-worth clients can cause financial advisors to be constantly reminded of those clients’ affluence, and how their own financial status compares.

The effects of social comparison on advisors’ self-worth can also be felt when advisors move ‘upmarket’, serving more affluent clients as they gain experience in their careers. Doing so can cause the advisor to move out of their financial comfort zone, because if they originally served clients who were closer to the advisor’s own peer group and upbringing, moving to serve clients of a different socioeconomic status can cause tension between the advisor’s own values and attitudes toward money and that of the clients they serve. Which can in turn cause the advisor to feel as if they are inadequate to serve their (more affluent) clients’ needs, or unable to relate to those clients’ goals and desires – either of which might cause the advisor to feel dissatisfied with their place in life and consequently lower their sense of self-worth.

It is important, therefore, for advisors to avoid the traps that could cause their self-worth to suffer from over-comparison to their high-net-worth clients (since serving these types of clients is, for many advisors, the hallmark of a successful career). One method is for advisors to mark their own progress over time, not only in terms of income and net worth but also in terms of skills and overall life satisfaction. Comparing our progress and improvement over time by benchmarking against our own past performance can help us feel (just as we often help our clients feel) the satisfaction of making progress toward our goals.

Another way to improve self-worth is for advisors to use their knowledge to help those who are less affluent, such as providing pro-bono financial planning to those who cannot otherwise afford professional advice. Aside from the intrinsic benefits of helping those who are less well-off, this can also serve to balance out the feeling of having only highly affluent clients and can help the advisor feel more confident and useful in their ability to provide valuable, impactful advice.

Ultimately, maintaining a healthy sense of self-worth is key for financial advisors to stay focused on themselves and the positive impact they are providing through their advice. While social comparisons are inevitable – being hard-wired into most of our brains – it is possible to reshape and augment those perceptions by deciding who to compare ourselves to, which gives us the power to determine (and improve) our own self-worth!

Self-Worth Is Contingent On How We Compare Ourselves To Those Around Us

Having a high level of “self-worth” – i.e., feeling good about one’s self and place in life – has long been recognized as a major driver of wellbeing. With the caveat that in practice, self-worth can be very difficult to measure; after all, there really is no quantitative measure of our ‘worth’ as a human being – to know whether it’s ‘worthy enough’ to feel good about. As a result, self-worth is often defined as a contingent construct, which means its measurement is contingent on something (or more often, someone) else.

In other words, because there is no natural system to ‘score’ whether someone is worthy enough to have an intrinsically high level of worth, having high self-worth often implies that a person thinks they are better than at least some other individuals. And ironically, while some books (and even some religions) strongly advocate the importance of finding one’s self-worth internally within ourselves – and not by comparison to others – the reality that these are teachings that some people spend a lifetime trying to learn simply reinforces how our natural state does tend to be comparative to others (i.e., as uncomfortable as that likely makes many readers feel, this is how researchers of self-worth define it, because it’s what we most often do as human beings!)

Except since we can’t necessarily measure other people’s level of intrinsic worth either, even social comparisons often rely upon more outward measures that we can see and evaluate. Notably, these comparisons can be ‘domain’ specific – one person may derive their self-worth from the domain of their job (and how it compares to others), while others may derive it from the domain of their family (and how the connections with their family compare to others).

But given that there’s no universal agreement about the ‘best’ jobs for social comparison, and measures like family are even harder to evaluate, in the end, social comparisons often come down to the most visibly quantitative measure: our finances. This is a view supported by researchers like Keith Payne, who wrote the book, The Broken Ladder: How Inequality Affects the Way We Think, Live and Die, which delves into when and why our self-worth often becomes tied to net worth.

But given that there’s no universal agreement about the ‘best’ jobs for social comparison, and measures like family are even harder to evaluate, in the end, social comparisons often come down to the most visibly quantitative measure: our finances. This is a view supported by researchers like Keith Payne, who wrote the book, The Broken Ladder: How Inequality Affects the Way We Think, Live and Die, which delves into when and why our self-worth often becomes tied to net worth.

An interesting example of this self-worth/social comparison phenomenon comes to us from a study by David Hemenway and Sara Solnick, professors at Harvard’s School of Public Health, who asked students about income. Students were asked to pick between two income situation options, and were told that they could assume the prices of goods and services would be constant:

Option 1: Earn $50,000 a year when others earn $25,000

Option 2: Earn $100,000 a year when others earn $250,000

The surprising thing was that 52% of students chose Option 1, where they would earn less income, as long as it meant that their earnings would still exceed what other people earned. The social stigma perceived to be associated with Option 2 – a higher absolute level of income, but one that is still much lower than peers – and its impact on self-esteem/self-worth, led fewer students in the study to choose Option 2 even if it meant they would earn half as much overall ($50,000 instead of $100,000)… simply to stay ahead of their peers.

For financial advisors, this study is especially relevant, as it highlights the power of comparison groups. After all, if so many of us evaluate our self-worth via a comparison group, it’s important to highlight how financial advisors compare. Importantly, when it comes to financial advisors, the good news is that most really do quite well for themselves (at least the ones who survive, and successfully ‘make it’ in their advisory career).

In fact, the latest Kitces Research study showed a median income for lead advisors of $155,000/year, more than double the average American household at about $68,700). However, the reality is that financial advisors don’t typically work with the median household – instead, advisors are disproportionately concentrated amongst the top 1/3rd of most affluent households – which makes the dynamics of self-worth and social comparison far more complicated.

Serving Affluent Clients May Negatively Impact Financial Advisors’ Sense Of Self-Worth

In 2020, Kitces Research conducted a study investigating advisor wellbeing, and the associated factors that lead to greater wellbeing of financial advisors. To measure wellbeing itself, the study used what is known as the Comprehensive Inventory of Thriving, a well-known positive psychology measure with 18 sub-scales looking at a wide variety of constructs that pertain to overall wellbeing.

Amongst those sub-scales is a measurement of self-worth, which was evaluated via the following three statements, where advisors could rate themselves on a scale of 1 to 5 (where 1 was equivalent to an answer of “Strongly Disagree”, and 5 was equivalent to an answer of “Strongly Agree”):

- What I do in life is valuable and worthwhile;

- The things I do contribute to society; and

- The work I do is important to other people.

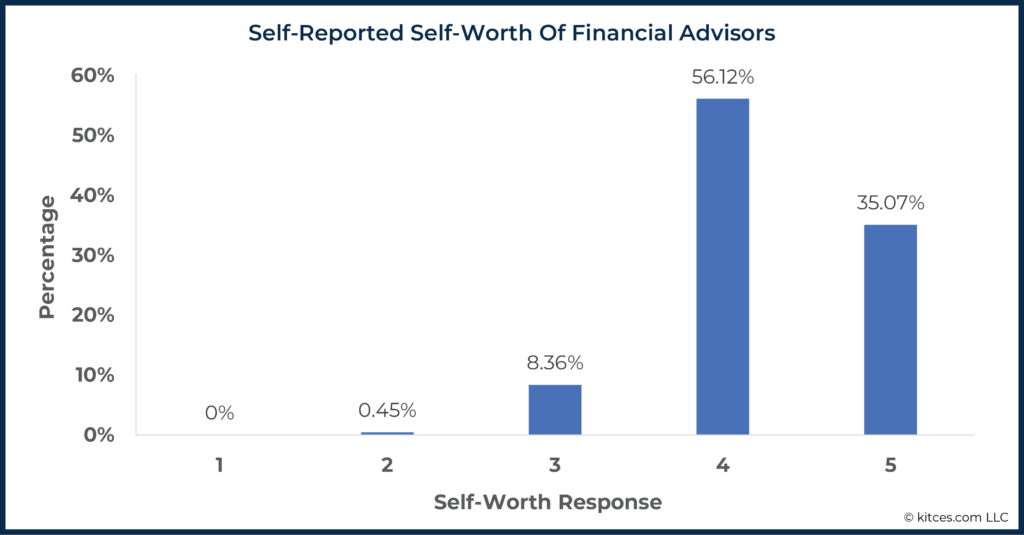

As seen in the chart below, the results paint a positive picture. Of the 670 respondents, most financial advisors (over 90%) rated themselves in the 4 to 5 range (with a mean of 4.23, and a standard deviation of 0.62), indicating that they either agreed or strongly agreed with the self-worth statement(s).

What’s even more notable in the context of self-worth – and its common framing around social comparison – is that advisor wellbeing is quite positive, despite the fact that financial advisors themselves tend to work with fairly affluent clientele. In fact, the aforementioned Kitces Research on Advisor Wellbeing found that the mean annual income of clients was over $200,000 (putting them in the top 20% of US households or higher), with mean investable assets of about $1,500,000, and a mean net worth of almost $3 million (where fewer than 5% of American households have a net worth over $3 million). Which suggests that the typical client of a financial advisor was (and continues to be) very affluent.

Still, not all financial advisors earn the same income – the low end of advisor income in the same Kitces Research study being approximately $95,000 (25th percentile), and the high end around $750,000 (90th percentile) – which means many might still not be as affluent as their clients. In addition, the reality is that not all financial advisors serve the exact same types of clients (with the same level of affluence). Which, from the broader research on self-worth and social comparisons, is important, as clients themselves can become a comparison group for financial advisors.

All of which raises the question: does being constantly reminded that their income and net worth levels are lower (sometimes much lower!) than that of their wealthiest clients impact how financial advisors think about themselves and their own self-worth? As it turns out, it does matter, as our Kitces Research Study shows a small but clear relationship between advisors’ self-worth and the affluence of their clientele!

As the results above show, financial advisor wellbeing generally declines as the net worth of their clients grows, particularly when working with millionaires and those even wealthier. The effect is most acute when working with clients with $5M+ of net worth – beyond the average net worth of most financial advisors themselves, a fact that advisors are constantly reminded of as they provide upfront and ongoing financial planning with their (most affluent) clients.

In other words, to the extent that self-worth is often driven by social comparisons to others, spending a lot of time with others who are ultra-high net worth (even in the advisor-client context) is still associated with a decrease in the advisor’s own reported self-worth. (And the higher the net worth of the clientele, the greater the adverse impact on advisor self-worth.)

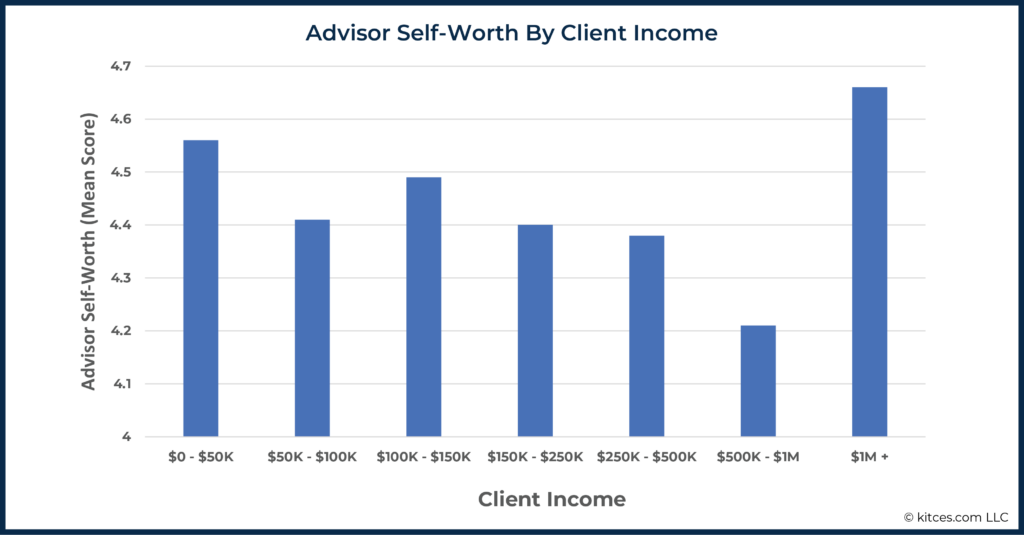

Notably, the challenge of social comparison of net worth may be exacerbated for financial advisors, who themselves tend to be very goal- and accumulation-oriented. Accordingly, comparisons of net worth with clients who have greater net worth may be especially grating. In fact, advisors appear to be so accumulation-centric that, when advisor wellbeing is evaluated relative to the income their clients earn, the exact opposite effect from the comparison against net worth emerges!

When it comes to client income, financial advisors tend to show rising levels of wellbeing as the income levels of their clients increase, especially when working with clients who make more than $1M/year in annual income. In practice, this is most likely related to the fact that clients with more affluence spend, at least on average, a greater dollar amount on ‘extravagant’ expenditures and aren’t always the best savers (at least relative to their much-higher income), as contrasted with more goal-oriented accumulation-minded advisors who may be more likely to save their income. Accordingly, some advisors might consider their clients’ spending behavior to be ‘wasteful’ and evidence of poor stewardship of their wealth, which may lead them to feel better about (and experience a greater sense of self-worth because of) how they steward their own income.

In other words, when it comes to high-net-worth clients, the advisor who hasn’t been able to accumulate as much wealth (yet!?) may feel pressured with respect to their own perceived self-worth. On the other hand, with high-income clients, the advisor may view ‘wasteful’ expenditures as an affirmation of their own more-prudent or frugal saving habits, boosting self-worth with respect to how they manage their income.

Which ultimately is another demonstration of the domain-specific nature of self-worth; relative to net worth, we may judge ourselves against the net worth of our clients, but relative to income, we judge ourselves not on the level of income but on the savings habits that go along with that income (where the advisor proudly sees themselves as having greater financial responsibility and impulse control when compared to their clients).

Notably, the declines in perceived self-worth associated with high net worth, along with the increases associated with greater client income, were not dramatic. Advisor self-worth scores shifted by 0.15 to 0.30 across the ranges of client income and net worth, respectively, relative to an overall advisor self-worth mean of 4.25, with a standard deviation of about 0.62. Still, the trends of declining self-worth (with rising client net worth) and rising self-worth (with rising client income) are clear, especially in their cumulative effect.

The Problem With Moving ‘Upmarket’ Out Of The Advisor’s Financial Comfort Zone

One of the biggest drivers of financial advisor income is simply their years of experience as a financial advisor. In part, this is simply due to the fact that it takes many years to accumulate a critical mass of clients (adding a handful each year while retaining the ones brought on in prior years). Though it is also driven by the cumulative effect of the advisor building their brand and reputation in their community (to generate greater inbound referrals).

In the end, though, the growth of an advisor’s reputation and experience not only allows them to attract more clients, but also typically to attract more affluent clients. Consequently, it is worth discussing how the wealth of financial advisors’ clients might influence an advisor’s self-worth as they progress through their careers.

Because as a financial advisor grows in their career, they may seek out wealthier clients to grow their businesses and increase their capacity, revenue, and income. Which means that, despite the success they may enjoy in achieving these goals, it is possible that their success may ultimately experience a negative impact on their sense of self-worth!

The evolution of an advisor’s career – and the clientele they serve – is further complicated by the fact that people often have a certain ‘financial comfort zone’ – the lifestyle (and peer group) to which they’re most accustomed. Such that moving out of one’s comfort zone by starting to spend time with a different (more affluent) crowd – such as more affluent clients – can create additional tension. If you have ever noticed in yourself that serving a certain client makes you bristle – this might be at least part of the reason!

Lora is a financial planner who grew up in a middle-class household, but now serves the ultra-wealthy. She makes quite a bit of money herself, and so now she feels that she no longer fits in exactly with her family. However, she doesn’t feel she makes enough to fit in with her ultra-HNW clients, either. As a result, Lora is not able to fit in well financially with her family, nor does she fare well when she compares herself to her clients. This combination makes Lora especially uncomfortable.

Nerd Note:

One way to conceptualize a “financial comfort zone” is socioeconomic status. Growing up in the middle class, a financial advisor may likely feel most comfortable with others also in the middle class (who have middle-class spending and lifestyle habits, and similar middle-class income and net worth). But as an advisor now working with high-net-worth and ultra-high-net-worth clients, their financial comfort zone is going to be stretched. They may not be able to relate to the way clients live their lives and may also feel uncomfortable not being able to keep up with them. They may even judge (and resent) clients for their wealth and the way they spend their money.

For another way to imagine how this could play out, consider the issue of countertransference – when an advisor inadvertently takes out their own financial stress, issues, or trauma on a client. Countertransference may very well be triggered by feeling inadequate in front of clients, and unless we talk about these things, or at least acknowledge that they certainly can happen (especially with data that reveal how factors such as income and net worth can affect an advisor’s sense of self-worth), we can’t get better or overcome it.

Lora notices that she cannot stand working with her client, Lloyd. Lora feels Lloyd is a lazy trust-fund kid. When Lloyd comes in with yet another ‘financial problem’, it makes Lora annoyed. She helps him because it is her job, but helping him does not make Lora feel all that great because Lloyd’s financial circumstances are outside of Lora’s financial comfort zone.

How Financial Advisors Can Protect Themselves From Self-Worth Traps

Advisors are not alone in gauging their self-worth using financial criteria, though it is interesting to consider how the finding that advisors serving ultra-high-income earners actually tend to have higher levels of self-worth might underscore the social comparison phenomenon even more. We cannot control that we do this; as human beings, we are social animals who want to feel good about how we see ourselves in comparison to others. This does not suggest we are evil or self-obsessed; it is simply a normal characteristic of all humans to want to fit in and feel good about ourselves.

Fortunately, the reality is that with above-average earnings and a strong psychic gratification for helping others, the majority of financial advisors who participated in our Kitces Research study had very positive levels of self-worth, which is a great indicator that many in our profession feel good about themselves and their work. Even so, it is natural for everyone to feel down every once in a while – particularly when meeting with especially affluent clientele. Learning how to maintain and increase self-worth can be a powerful way to combat the blues.

Compare To Your Own Progress (For Your Income, Net Worth, Or Skill Development)!

While self-worth is hard to evaluate without comparing to something, comparing to others in our personal sphere – whether ‘the Joneses’ we live next to, our friends and colleagues, or our clients – isn’t the only way to compare. Another way to compare is to ourselves… in the past.

For instance, consider where you were five years ago. How have you grown? How has your income, assets, or skills as an advisor (and the associated life satisfaction) changed for you? Odds are good that you have changed more than you may realize. And going hand in hand with that is the realization that you have the ability to change even more in the future. Especially if creating change in yourself (to improve how you perceive your self-worth) is your goal.

Research by Jennifer Crocker and Katherine Knight, professors of psychology at the University of Michigan, suggests that individuals can take more control of developing their self-worth by thinking more critically about making changes – in particular, by consciously considering actions that can be controlled and that will help how self-worth is perceived. Or stated more simply, we can increase our self-worth by setting goals for ourselves that we believe we can (and subsequently take action to) achieve.

Fortunately, the reality is that setting goals and charting a course of action to achieve them is a natural part of the financial planning process in the first place, something we can apply internally to ourselves as much as we apply externally to clients. In fact, our original Kitces Research Study on How Financial Planners Actually Do Financial Planning examined advisor personalities and motivations, and found that advisors really do have a natural tendency to set goals and meet them (we score especially high on accomplishment and self-efficacy)!

The key, though, is to keep our eyes on our own goals, even as we sit daily across from clients working with them to achieve their (potentially more affluent) goals. Which ultimately means more than just writing down our own goals to identify them. It means creating a spreadsheet (or using financial planning software on ourselves) to track our own progress over time, so we can reflect on the social comparison not of our own finances to our clients, but our finances compared to ourselves from 3, 5, or 10+ years ago.

Help Those Who Don’t Have As Much As You

While our Kitces Research shows that advisors working with more affluent clients may experience at least a slight diminishment in their own feelings of self-worth by spending so much time with those who have more, it also highlights the reality that we can also improve our own feelings of self-worth and increase the gratitude for what we have by working with those who are less affluent.

Doing pro-bono work, or taking on at least a few clients who may be below our minimums as a conscious exception to serve those with a little less (i.e., instead of serving wealthier and wealthier clients, consider creating holding space to be able to serve a few more middle-income households) can help advisors recalibrate their own feelings of self-worth.

After all, feeling good about helping someone who is in a relatively tougher or worse position is not an indicator that someone is evil or bad. There is a big difference between feeling confident, useful, and skilled in what we have to offer to help those less fortunate (which is great), and feeling arrogant and using your skills to bully, intimidate, or feed one’s ego. There is absolutely nothing wrong with purposefully working with clients who make an advisor feel confident and useful!

Here are a few ways that advisors can find pro bono work or clients who need help and who might not fit the ‘traditional’ financial planning client:

- The Financial Planning Association (FPA) Pro Bono Program helps to connect interested financial planners with individuals, families, and wider communities that need financial planning services.

- The Foundation for Financial Planning also has a pro bono program. The Foundation's program allows planners to find individuals and families in need, but they also have support for financial advisors who want to start their own in-firm pro bono program.

- The National Association of Personal Financial Advisors (NAPFA) also has a pro bono program where advisors can list themselves as pro bono advisors.

- For financial planners interested in tax planning, the IRS offers Volunteer Income Tax Assistance (VITA) programs.

The work that advisors do, for all of their clients, is really important. And an important aspect of being great for them is for advisors to feel good and confident about themselves. There are always going to be clients (maybe even groups of them) that make us feel a bit uncomfortable – we don’t like the way they spend their money, we don’t feel they truly appreciate what they have, we simply can’t get past how much they have or how they earned it and how our path has been different or harder. While these can be uncomfortable questions and lines of thought, they are not unimportant or even uncommon. Embracing how you feel and making changes to feel better are powerful actions – your internal work matters to the work you do with clients, so give it your all.

Having high self-worth is important. Everyone wants to feel good about themselves and yet, self-worth is a rather fragile construct in that it relies on social comparisons to those around us. Moreover, advisors may very well find that their self-worth declines as they start to move upstream, which can unwittingly lead to them spending too much time comparing themselves to their (even more affluent) clients. And if this happens, just know that you are normal and that you can make changes – you don’t have to chase the Joneses or beat the Joneses to feel better.

Instead, focus on comparisons to yourself and how far you’ve come from where you were. Are you doing better than you were five years ago? Are you actively tracking personal and professional growth and taking the time to celebrate and acknowledge those wins? If not, this can be a valuable yet simple way to get started and build self-worth.

Another strategy is to share your gifts! Pro bono work is a great way to give back. Even working with a non-traditional client every now and again can help boost feelings of confidence and usefulness, which is incredibly empowering – not only for you but also for those that you serve!