Executive Summary

In a world where it’s hard to regulate the wide and ever-changing world of advertising, one of the most common frameworks that regulators take is a ‘truth-in-advertising’ approach that simply requires whatever advertisers say or claim to be true and accurate. In recent years, regulators have begun to consider whether this approach should be applied in the world of financial advice, as consumers engage with both advice-providers and brokerage salespeople… all of whom use increasingly similar “financial advisor”, “financial consultant”, “financial planner”, and similar titles. Which has led to both the original SEC Regulation Best Interest proposal to restrict the use of the term “advisor”, and states such as Nevada proposing to regulate a(n even broader) list of titles that includes not only "financial advisor", but also terms like "financial planner", "retirement consultant", etc.

However, when it comes to understanding the extent to which “advisor” titles are truly confusing to consumers (or not), the research available has actually been quite limited. Is title confusion actually a big issue that severely leads consumers astray? And, to the extent that confusion does exist, what types of titles or policies might better promote consumer clarity?

A recent study published in the International Journal of Consumer Studies explored these questions directly, by testing (a) how consumers perceive "financial advisor" and similar titles, and (b) the extent to which clarity could be improved through the use of disclosures. The study found that, in practice, titles do matter, consumers do have substantively different expectations regarding both the competency and loyalty (i.e., trustworthiness) of those who use “financial advisor” or especially “financial planner” as their title in lieu of "stockbroker" or "insurance agent", and that more generally consumers do distinguish between sales-oriented titles and advice-oriented titles.

On the other hand, the research also shows that disclosures do matter as well, and in fact, when consumers see both a title and a disclosure, it’s actually the disclosure that was found to matter more. On the plus side, this means that the prospective harm of misleading titles (e.g., salespeople using advice-centric titles) can potentially be ameliorated by having clear disclosures about their true role as a salesperson or advisor. On the minus side, though, the research also shows that when disclosures are themselves not well crafted, consumers can misinterpret a salesperson to be subject to a higher standard than the title actually conveys as a result of the unclear disclosure.

Ultimately, this suggests that regulation of advisors in the future will likely necessitate a combination of both clearer oversight of titles, and the use of clear(er) disclosure. For instance, a ‘safe harbor’ approach of setting certain titles that can be safely used by salespeople or advisors, respectively, provides a framework for consumers to understand the types of people they can engage, and can be a good system to help bring the ‘whack-a-mole’ style of title switching to a stop. At the same time, though, further scrutiny of disclosures becomes crucial, as disclosures help to bridge the gap in consumer clarity for an ever-changing landscape of titles that may not (yet?) be regulated, but also run the risk of causing further consumer confusion if the disclosures don’t create an accurate understanding for consumers of whether they are engaging a product salesperson or an advice-provider.

Proposed Regulation Of Financial Advisor Titles

It’s no secret that “financial advisor” has become a ubiquitous term. In large part because it helps to be thought of as an “advisor” rather than a “salesperson”, the term has become widely used by everyone, from fee-only financial advisors who operate to a legal fiduciary standard at all times, to purely commissioned salespeople who aren’t even licensed to give investment advice.

Unfortunately, this overlap in financial advisor titles has caused consumer confusion. When everyone calls themselves an “advisor”, it’s not clear who lives up to the name because they’re actually in the business of advising, and who is simply using advice as a means to sell a product pursuant to that advice. In other words, consumers may at times want to hire a salesperson to implement a product, and at other times may want to seek out advice… but it’s impossible to make the choice between advice and sales when titles fail to distinguish between the two.

Accordingly, regulation of how the “advisor” title is used was recently under consideration at the Federal level under the initial Regulation Best Interest (“Reg BI”) proposal put forward by the SEC. Specifically, the initial proposal would have prohibited the use of “adviser” or “advisor” as titles by representatives of a broker-dealer. The justification for this proposal was that representatives of broker-dealers legally are in the business of selling securities products (through the broker-dealers and product manufacturers they represent) and are not licensed to be compensated for advice itself… and therefore it would be misleading to use the term “advisor” to describe what they do for clients.

Of course, the reality is that in today’s environment, few people who call themselves advisors today work solely in the capacity of a representative of a broker-dealer. Rather, even those who may primarily act in this role often do carry the licensure required to also act as a representative of an investment adviser, and therefore bring the ‘dual-hat’ issue of advisor registration. And the SEC proposal would not have prohibited a dually-registered advisor from using the term “advisor”, even in a context where it would be highly unlikely that they would serve a client in a fiduciary advice capacity (i.e., the SEC would have permitted dual registrants to call themselves “advisors” even if in practice 99%+ of their business was still operating as a brokerage salesperson and not in an advice capacity). Therefore, the actual proposal would have likely had limited impact, and was ultimately abandoned in the final Reg BI rule anyway. Furthermore, the SEC proposal would have done nothing to prevent advisors from simply adopting similar terminology (e.g., “financial consultant”) to still use a title that would likely be perceived similarly to “financial advisor” but isn’t specifically a prohibited title.

Frustrated by a lack of Federal regulation, some states have stepped in to start proposing their own title regulations. For instance, the Nevada Securities Division recently proposed that a more comprehensive list of terms be regulated, including titles that contain any of the following: adviser, financial planner, financial consultant, retirement consultant, retirement planner, wealth manager, or counselor. Under Nevada’s proposed regulation, if a representative used any of these terms in their title, name, or biographical description, it would limit their ability to claim an exemption from meeting a fiduciary duty. For instance, if you called yourself a financial advisor in Nevada, you would be automatically deemed as being in the business of advice, and thus held to a fiduciary standard typically applicable to those providing advice… preventing the broker from falling back on a claim that they were wearing their non-fiduciary broker hat at the time they were selling a particular investment product in order to be eligible for the lesser standard of care for brokers.

Nevada’s proposal was interesting from the perspective of not limiting the use of the proposed terms to be regulated, but simply making professionals adhere to a fiduciary duty if they were using titles that would be perceived to imply that they were offering financial advice. Furthermore, Nevada’s proposal went further to prevent advisors from also using similar terminology (without meeting a fiduciary standard) rather than the more limited proposal from the SEC of prohibiting certain individuals from calling themselves “advisers” or “advisors”.

The list of titles selected by the State of Nevada’s proposal was itself also interesting. For instance, why regulate “financial consultant” and “retirement consultant” rather than just the more general term of “consultant”? It’s doubtful that their intent was for titles like “investment consultant” to be okay for anyone to use without a requirement to adhere to a fiduciary duty, but it’s not clear if that title would be prohibited under the proposed rule. Granted, Nevada regulators did propose the authority to add terms to the regulated list as they saw fit, but this highlights the inherent difficulty of trying to maintain a list of regulated titles. Regulation becomes a ‘whack-a-mole’ type of endeavor, where regulators are constantly chasing whatever new term has emerged that is not specifically prohibited.

Do Financial Advisor Titles Matter?

It seems quite logical that titles used by financial advisors do matter, especially when those titles are what prospects often use to identify a suitable overseer of their life savings and financial futures. Surprisingly, though, the research exploring how individuals perceive different titles, and demonstrating the relative importance of titles in influencing consumer perceptions, is actually quite limited. Which offers ample opportunity for new research studies to examine these very issues.

Past Research Highlights Consumer Confusion Over Titles Used By Financial Professionals

Recognizing the importance of consumer perception of advisor titles, the SEC has commissioned multiple research studies over the past two decades. For instance, in 2004, the SEC sponsored a study that involved four 90-minute focus group sessions to explore how consumers understand the roles and differing legal obligations of representatives of investment advisors and broker-dealers.

The results from this focus study, which included interviews with groups in Maryland and Memphis, appear to validate that consumer confusion does exist. However, the small sample size (8 or 9 participants in each session) and limited scope of demographic range left a lot to be desired. Importantly, the study did not examine issues directly relevant to title regulation (e.g., do consumers perceive "financial advisors" and "financial planners" similarly?).

2006 SEC-Sponsored RAND Survey

In 2006, the SEC sponsored a RAND survey of 654 participants that did specifically look at consumer perceptions of various titles commonly used by financial advisors. Specifically, the study looked at perceptions of what types of services would be provided by a professional using a certain title (e.g., investment advisor, broker, financial adviser or consultant, and financial planner).

The results did reveal that misperceptions exist within the marketplace. For instance, only 49% of consumers surveyed understood that investment advisers are required by law to adhere to a fiduciary duty, while 42% also thought that brokers were required to act in a client’s best interest even though they’re not actually regulated as advice-providers.

2010 ORC/Infogroup Study For The Consumer Federation Of America

In 2010, ORC/Infogroup was commissioned to do a study for the Consumer Federation of America. The study surveyed 2,012 individuals and examined perceptions of titles that included investment adviser, financial adviser, financial planner, stockbroker, and insurance agent.

Again, significant confusion was observed. For instance, two-thirds of participants thought that stockbrokers are held to a fiduciary duty for their advice. This study did have a significant limitation, however. The survey was designed with a number of ‘double-barreled’ questions (i.e., questions that involve two more statements, making it impossible to discern which part, in particular, an individual was actually responding to). For instance, one survey question asked (lettering in bold added):

Some financial professionals are required to comply with what is called a ‘fiduciary duty’ which means that they are required to (a) put your interests ahead of theirs when making recommendations, and (b) tell you upfront about any fees or commissions they earn and any conflicts of interest that potentially could bias that advice. Based on your understanding, which of the following types of financial professionals are required to uphold this standard?

Now suppose that a survey respondent indicated that they believed this was not true of stockbrokers. We don’t know if they felt this wasn’t true because part (a) was true, but part (b) was not; part (b) was true, but part (a) was not; or neither part (a) nor part (b) was true. This is an important limitation because it severely limits our ability to look at the results and discern specifically where any confusion may be occurring. And this same type of question was used several times within the study.

Furthermore, there was an added issue with respect to the use of descriptive (i.e., reporting of what’s true) versus normative (i.e., reporting of what ought to be) issues in the ORC/Infogroup study. Only one of the primary questions within the ORC/Infogroup study was descriptive in nature (i.e., examining what is), with most being normative (i.e., examining what respondents believe ought to be).

The distinction matters because while normative consumer research is important (for example, it would be useful to identify important misalignments between what consumers believe ought to happen in the marketplace and what actually does happen), normative questions do not get at the issues of whether confusion actually exists in the marketplace. After all, it could be that consumers think that something should be done differently, without realizing it’s actually how the system currently works already, but they just didn’t understand it (which would indicate that regulation is needed to promote greater marketplace clarity). Or, alternatively, it could be that consumers do understand how things are done in the marketplace, yet just don’t believe that’s how things ought to be done, which would significantly reduce the justification/need for regulatory intervention.

For instance, suppose consumers think that all cars ought to come with built-in smoothie makers. If these same consumers understand that no cars currently come with built-in smoothie makers, then we’re just dealing with a matter of consumer preference, and the case for automobile smoothie-maker regulation is very weak. If, however, consumers were somehow under a widespread misconception that many cars already come with built-in smoothie makers, then the case is stronger for regulation to promote greater marketplace clarity and help consumers better understand what is (and isn’t) already included.

2018 SEC/RAND Focus Group Studies

In 2018, the SEC’s Office of the Investor Advocate and the RAND Corporation again conducted focus groups and a survey of 1,816 US adults. This study also identified confusion among many consumers with respect to their awareness of whether they were working with sales representatives of broker-dealers or investment advisers providing advice.

This research was unique in that the study actually followed up using the Investment Adviser Public Disclosure (IAPD) database to assess how well consumers correctly identified whether their advisor was a representative of an investment adviser, broker-dealer, or dually-registered (consumers could also indicate they did not know, although only 6% selected this option).

Despite only 34% of consumers thinking they worked with a dually-registered individual, this number turned out to be closer to 70% of the advisors that could be identified. Furthermore, among those who were actually working with a sales representative of a broker-dealer, 74% mistakenly thought they were working with a representative of an investment adviser who was in the business of advice (and thus would be a held to a fiduciary standard for that advice).

This 2018 SEC/RAND study also generated some interesting findings regarding perceptions of the professional roles of those using various titles. Consumers perceived financial advisers, financial consultants, and financial planners as more similar to investment advisers (providing advice) than to brokers (selling products). However, consumers differed in some ways with respect to their perceptions of investment advisers versus financial planners, financial consultants, and financial advisors; the study indicated that they perceived titles beginning with “financial” as more comprehensive in nature, and less likely to recommend specific investments. Yet while this most recent study again illustrated consumer confusion, there were still a number of ways in which it still did not provide the type of insights into consumer perceptions that are directly relevant to questions of title regulation.

Ultimately, while conventional wisdom and prior research do both point to confusion existing around titles, that confusion has not been empirically demonstrated in an ideal manner.

New Research Examines Nuances Of Title Perception Across A Two-Dimensional Framework

To address the limitations of past research, I conducted a recent study, originally published as a Mercatus Center Working Paper and accepted in the International Journal of Consumer Studies, to get at the issue of consumer perception of various titles in a more direct manner than prior research. The study itself consisted of two underlying studies; the first was designed to examine consumer perceptions of titles used in financial services, and the second to explore the relative importance of both titles and disclosure on consumer perceptions.

In the first part of the study, a theoretical framework of linguistic perception was used to empirically measure consumer perceptions. This framework was based on the theory that adjectives used by humans to describe things in our environment vary across three important dimensions: Evaluation, Potency, and Activity. These three dimensions make up the “EPA” linguistic framework, which has received significant empirical support dating back to the 1950s.

Essentially, similar to how the Fama-French three-factor model identifies the three factors that explain the bulk of the differences in stock returns (market premium, value premium, and size premium), the EPA is a three-factor model that identifies the three linguistic factors that contribute the most to differences among adjectives (evaluation, potency, and activity).

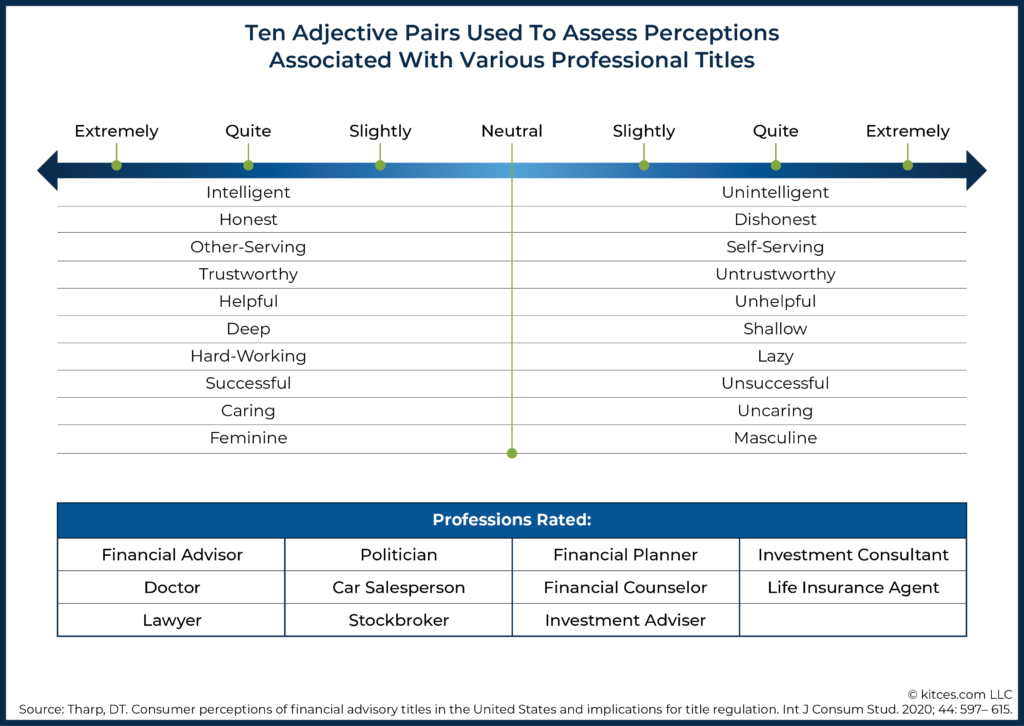

Adjective pairs (e.g., intelligent/unintelligent) that had been psychometrically validated in prior research were selected that spanned these three different EPA dimensions. Specifically, adjectives assessed included in this study included honest/dishonest, intelligent/unintelligent, other-serving/self-serving, trustworthy/untrustworthy, helpful/unhelpful, deep/shallow, hardworking/lazy, successful/unsuccessful, caring/uncaring, and feminine/masculine.

In other words, participants would see a title (e.g., “financial advisor”) and then were asked to rate that title on adjective pairs ranging from extremely intelligent on one end of a spectrum and extremely unintelligent at the other end of the spectrum (with options of “quite” and “slightly” also available on each side of a neutral option).

This process was repeated for each of the adjective pairs above among a sample of 665 US respondents who were asked to rate a set of professional titles. Everyone was asked to provide an assessment of doctor, lawyer, politician, car salesperson, financial advisor, and investment salesperson.

To get a broader representation of financial services titles, without making it overly obvious what the focus of the study was, each participant was also asked to assess one of the following: stockbroker, financial planner, financial counselor, investment adviser, investment consultant, and life insurance agent.

Additionally, participants were then asked to select which financial title they would be most likely to reach out to if they were to seek professional services across a range of financial domains, including budgeting, managing day-to-day cash flow, saving, investing, making large purchases, buying life insurance, buying home and auto insurance, and planning for retirement.

The adjectives analyzed were found to broadly contribute to one of two dimensions. Specifically, honest, caring, other-serving, trustworthy, helpful, and deep all loaded onto a factor that was interpreted to broadly reflect “loyalty”. Additionally, successful, intelligent, and hardworking all loaded on a second factor, which was interpreted to reflect “competence”.

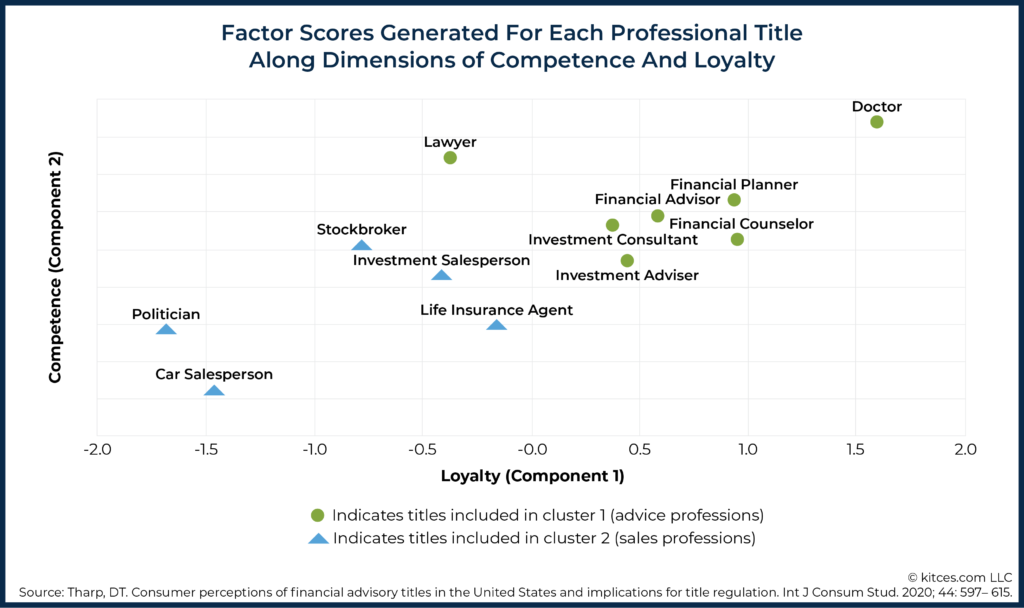

With factor scores extracted to reflect assessments of both “loyalty” and “competence” for each title, the titles, which were categorized as representing either service or advice professions, could be plotted against one another on a two-dimensional graph of loyalty and competence, to see how consumers rated each title on these dimensions.

Not surprisingly, “doctor” and “lawyer” rated significantly higher than all other titles in terms of competence. Interestingly, however, "lawyer" rated slightly negatively in terms of loyalty, whereas "doctor" rated highest of all on loyalty.

"Politician" and "car salesperson" were standouts in terms of rating very low on both competence and loyalty.

Among the financial titles, “financial planner” rated above all other terms on both competence and loyalty. This likely reflects the efforts that have been put in by the CFP Board and its public awareness campaign, along with membership associations like NAPFA and its strong media relations, to raise the status of the term “financial planner”. Interestingly, however, it also highlights the potential risk of the proposed-but-abandoned SEC rule of regulating just the “financial advisor” title, when, at least, according to this study, “financial planner” would be a comparable unregulated term that is perceived in even higher standing within the marketplace (which also suggests it would be even more problematic when used by non-fiduciary salespeople).

What’s also notable about the financial titles is the clustering that we see formed. A cluster analysis was conducted to statistically test and confirm what seemed to be visually apparent – that titles considered within this study broadly clustered into two groups: advice professions (doctor, lawyer, financial advisor, financial planner, investment adviser, investment consultant, and financial counselor) and sales professions (politician, car salesperson, stockbroker, life insurance agent, and investment salesperson).

In other words, using a psychometrically validated approach to assess consumer perception, this study found that important perceptual differences exist between titles perceived as sales-oriented (which respondents assessed as relatively less loyal and less competent) and titles perceived as advice-oriented (which were assessed as relatively more loyal and more competent). Or stated more simply, consumers really do appear to rely on titles to understand the important distinctions between salespeople and advice-providers.

Do Disclosures Matter In Sales Versus Advice?

The second study included within my International Journal of Consumer Studies paper explored the relative importance of both titles and disclosure. As while title regulation (i.e., limiting or restricting the use of certain titles) is one approach to try and promote consumer clarity, alternatively regulators can also use disclosures to explain the differences in professional roles to accomplish the same purpose. In fact, adopting a disclosure-based approach over a title-regulation approach is arguably what the SEC did in their final Reg BI rule, utilizing Form CRS to disclose to consumers the difference between brokers and investment advisers.

To test the relative importance of disclosures and titles, participants in a second study of US respondents (with incomes of $75,000 or higher) were shown a 2x2 experimental design—meaning that participants were randomly assigned a series of prompts that included one of two titles (either “financial advisor” or “stockbroker”) and one of two disclosures (either an “advisory disclosure” or a “brokerage disclosure”). Disclosures were generated from hypothetical disclosures provided within the Reg BI proposal.

Specifically, the disclosure-related prompt that study participants received stated, “Imagine you have just hired a [financial adviser/stockbroker]. He/she provides you with some disclosure information that includes the following.” And then participants were randomly assigned either the advisory disclosure for a professional held to a fiduciary standard or a brokerage disclosure for a professional held to the newly developed Best Interests standard.

Specifically, here are the disclosures provided in the study (and modeled after proposed disclosures from the SEC):

SEC’s Advisory Disclosure:

Imagine you have just hired a [financial advisor/stockbroker]. He/she provides you with some disclosure information that includes the following:

- As your [financial advisor/stockbroker], I am held to a fiduciary standard that covers our entire investment advisory relationship with you. For example, I am required to monitor your portfolio, investment strategy, and investments on an ongoing basis.

- My interests can conflict with your interests. I must eliminate these conflicts or tell you about them in a way you can understand, so that you can decide whether or not to agree to them.

- If you open an advisory account, you will pay an on-going asset-based fee at the end of each quarter for our services, based on the value of the cash and investments in your advisory account.

SEC’s Brokerage Disclosure:

Imagine you have just hired a [financial advisor/stockbroker]. He/she provides you with some disclosure information that includes the following:

- As your [financial advisor/stockbroker], I must act in your best interest and not place my interests ahead of yours when I recommend an investment or an investment strategy involving securities. When I provide any services to you, I must treat you fairly and comply with a number of specific regulations. Unless we agree otherwise, I am not required to monitor your portfolio or investments on an ongoing basis.

- My interests can conflict with your interests. When I provide recommendations, I must eliminate these conflicts or tell you about them and, in some cases, reduce them.

If you open a brokerage account, you will pay a transaction-based fee, generally referred to as a commission, every time you buy or sell an investment.

So, in total, there were four different combinations of title and disclosure that study participants may have seen:

- Financial advisor with advisory disclosure;

- Financial advisor with brokerage disclosure;

- Stockbroker with advisory disclosure; or

- Stockbroker with brokerage disclosure.

After reading the disclosures provided, participants were asked to provide perceptions related to three different prompts:

(a) In this case, my [financial adviser/stockbroker] would receive a commission on financial product purchases that they recommend to me.

(b) In this case, my [financial adviser/stockbroker] would be required to act in my best interest when providing recommendations.

(c) In this case, my [financial adviser/stockbroker] must act as a fiduciary when providing recommendations to me.

The structure of this experiment—varying both titles and disclosure—provided an opportunity to empirically assess whether title effects or disclosure effects had a larger impact on consumer perception.

While a full dive into the results of that study is beyond the scope of this blog post, the key insight was that while both title effects and disclosure effects on consumer perception were observed, disclosure effects were much larger and more important than title effects, with respect to promoting consumer clarity.

For instance, when only seeing the term “financial advisor” or “stockbroker” (i.e., before disclosures were provided), consumers reported greater uncertainty regarding whether a “financial advisor” would receive commission compensation. Specifically, the probability of reporting uncertainty of how a professional was paid increased by 5 percentage points when seeing the “financial advisor” title rather than the “stockbroker” title.

However, once disclosures were provided, the title effects were no longer observed. In other words, if consumers received the clear disclosure that the financial advisor or stockbroker received commissions, then perceptions of the compensation and/or professional responsibilities were similar regardless of the title used.

The sizes of disclosure effects were also significantly larger. For instance, being presented with the brokerage disclosure (versus the advisory disclosure) was associated with an increase of 0.22 (for “financial advisors”) or 0.24 (for “stockbrokers”) in the probability of agreeing that a professional would receive commissions for the products they recommend.

Similar results were observed for the other factors considered in this study (i.e., whether the professional would be required to act in the client’s best interest, and whether they would be required to act as a fiduciary when providing recommendations). In short, both title and disclosure effects were observed to impact consumer perception, but disclosure effects tended to be considerably larger than title effects, and the title effects were often not observed once disclosures were also provided.

However, there are some important caveats to note with respect to this study. First, the findings regarding the relative importance of title effects and disclosure effects only hold if people actually read disclosures in the first place… and we know that in the real world, this isn’t often the case. Like most experimental psychology work, the context here is a bit contrived in that participants were presented with a short task (read the disclosure) that was occurring in a context that was very different from how a consumer may actually view (or rather, not fully view) disclosures when hiring a professional.

This limitation should not be understated. This study found that if individuals actually read disclosures, then potentially misleading perceptions of different titles can be overcome. But this is a big if. If, instead, in the real world, people tend to gloss over disclosures, then in practice the fact that disclosures have a greater effect is a moot point, because consumers may mostly or fully rely on title perceptions alone without getting to the disclosures. Or, to put it differently, if disclosures are going to be relied on, then it is essential to have a means to ensure that disclosures are really read.

Furthermore, it is likely also the case that titles used are themselves related to real-world disclosure-reading behavior. If, for instance, an advisor is using what this study has shown is a high trust title (and therefore leading a prospective client to believe that the individual is acting in an advice-giving fiduciary capacity that wouldn’t necessitate material disclosures), it’s likely that a consumer’s propensity to read a disclosure will be lower than when they are aware that they are dealing with a salesperson (titled as such).

Again, disclosures trump titles when disclosures are actually read, but if certain titles dissuade consumers from reading disclosures in the first place, relying on disclosures that may contradict titles (e.g., permitting “advisor” titles with disclosures that explain the individual may actually be acting in a sales capacity instead) could actually be harmful to consumers.

Another caveat regarding the findings with respect to the relative importance of title effects and disclosure effects is that disclosures can both inform and misinform. To the extent that any disclosures are misleading regarding capacity – e.g., utilizing a stockbroker title with a “best interests” disclosure for a broker who is not actually subject to a fiduciary obligation to act in the client’s best interests at all times – consumers may actually have a lesser understanding of their broker or advisor’s role. And in fact, this study showed that based on the use of the sample disclosures provided by the SEC under the Reg BI proposal, consumers reported a greater likelihood of thinking that brokers (rather than advisors) needed to act in their best interest as a fiduciary would!

This was almost certainly an artifact of the “best interests” standard introduced in the Reg BI proposal, and the similar language used in the SEC proposal samples (i.e., the proposed language literally used the term “best interests” rather than the lesser-known term “fiduciary”), but this highlights the fact that “best interests” may itself be significantly better understood than “fiduciary” by consumers. This could suggest that some consumers may actually develop a more favorable impression of advisors held to a “best interests” standard than advisors who describe themselves as being held to a “fiduciary” standard, and because of the “power” of disclosures when read, consumers may even misinterpret a stockbroker titled as such being held to a fiduciary best-interest standard under Reg BI’s “Best Interests” disclosures that are actually supposed to highlight the broker is not held to a fiduciary best-interests standard!

Practical Implications For Promoting Greater Consumer Clarity

There are several key takeaways from my recent study that are relevant to promoting greater consumer clarity. First, titles do matter. This study provided the first empirical evidence using psychometrically validated methods to demonstrate that consumers do actually perceive advice-focused and sales-focused titles differently. Which means that how titles are used does create expectations in the consumer’s mind, even before they meet with their advisor or broker, about what the nature of the relationship will be… which may or may not reflect the actual nature of their relationship to the client and the advice-versus-sales capacity they may be operating in.

Furthermore, the title “financial planner” was held in particularly high regard, scoring the highest in terms of both perceived competence and loyalty. This may suggest that “financial planner” should be given particular consideration when thinking about potential title regulation. For instance, the SEC’s proposed policy that would have regulated the use of “financial advisor” but not “financial planner” would have likely led to many brokers simply shifting from describing themselves as financial advisors to financial planners. Which could then actually amplify consumer confusion about the role of brokers versus advisors.

While the more comprehensive list of titles regulated under proposals from states like Nevada would capture a number of titles under regulatory scrutiny, it is also worth noting the inherent difficulty of trying to maintain an ever-growing list of titles that the regulator may seek to bar from use by salespeople.

Instead, a “safe harbor” approach to using titles may actually be a better course of action to pursue. Rather than maintaining a growing list of potential titles that could be confusing to consumers, regulators could instead establish a small list of titles that have been demonstrated to be reasonably well understood by consumers, and then designate these titles as “safe harbor” options that firms can opt to have their representatives use without regulatory scrutiny.

For instance, advisors selling investment products could choose to refer to themselves as a “stockbroker” or an “investment salesperson” without fear of being determined to be using a misleading title. If, however, companies choose to still use terms like “financial advisor” when selling investment products, then they would open themselves up to additional scrutiny of whether their approach to selling products is truly consistent with the use of the “advisor” title. Similarly, firms that used titles like “financial planner” would automatically be deemed to be operating as fiduciary advisors, since that term goes outside of the “safe harbor” of terms that are generally understood to be sales-oriented.

Notably, this approach would maintain greater freedom for firms in the marketplace who may feel that their approach to selling investment products truly does live up to use of the “advisor” title, while also being likely to lead many (most?) firms to take the risk-averse approach and simply stay within the “safe harbor.”

Or, alternatively, another more principles-based approach is simply to take a ‘truth-in-advertising’ framework that stipulates, “if the professional uses a title that a consumer would reasonably interpret as connoting an advice relationship, and not a sales relationship, the professional will be held to the (fiduciary) advice standard”.

As with any principles-based regulation, that determination is made on a facts-and-circumstances basis, using accepted industry practices (such as how the fiduciary standard works now). Which would also make it naturally dynamic to a changing marketplace – when consumers interpret a newly-emerged title as connoting an advice relationship, then it does. And therefore, there’s no need to play regulatory whack-a-mole with specific titles.

In such an environment, firms that don’t want to ‘risk’ being caught afoul would generally choose titles and proactive disclosures to make it crystal clear they’re not acting in that capacity. For instance, consider how firms proactively avoid using “tax” titles, and give “no tax advice” disclosures, all to make it crystal clear they’re not engaging in (regulated) tax advice as non-CPAs.

Of course, significant challenges would still remain with respect to the majority of advisors who can both sell products and act in a fiduciary capacity. The approach of simply allowing anyone to use the title “advisor” so long as they do some business in an advisory capacity is likely not ideal, as that creates a dynamic where a consumer may think they are getting financial planning advice from a financial advisor, but are actually being sold a product by a salesperson who isn’t required to provide guidance in accordance with their best interests.

Perhaps one solution would be to actually require the use of multiple titles. If an advisor consistently described themselves as “Financial Advisor and Investment Salesperson”, that at least draws attention to the fact that they do work in multiple capacities.

Another major takeaway from this study, however, is that title effects seem to be significantly smaller than disclosure effects. Therefore, crafting disclosures that consumers will actually read is especially important, as it can counteract even ‘problematic’ titles that advisors and brokers may use (and/or obviate the need to regulate titles at all).

Yet on the other hand, as this research also highlights, relying on disclosures also puts a significant burden on crafting the ‘right’ disclosures, which is challenging unto itself, as consumers appear to be interpreting the SEC’s “Best Interests” disclosures as implying a higher standard of care for brokerage salespeople than for those actually in the (fiduciary) advice business. While at the same time, there is also a question of whether certain high-trust (e.g., “advisor” or “planner”) titles may dissuade consumers from reading disclosures in the first place (making their potentially clarifying benefit a moot point).

Despite the many challenges of helping consumers better understand the roles of financial services professionals, it is still important to acknowledge that when consumers were given disclosures, they were significantly more likely to understand how advisors and brokers operated, and that once read, their understanding was not influenced by titles used. Which suggests that while the use of different titles does introduce some confusion, the best way to promote clarity may actually be to worry less about titles that are used and worry more about crafting disclosures that empower consumers to make informed decisions. But only if regulators can ensure that disclosures will actually be read, and that the use of high-trust titles doesn’t reduce disclosure-reading behavior of consumers in the first place.

Of course, this still opens up a whole set of questions regarding what ‘effective’ disclosures should ideally look like. Disclosures that are easily ignored may be of little use, and the common practice of burying disclosures in a mountain of legalese would not be an effective form of disclosure either.

Simpler, summary disclosures consistent with standardized mortgage disclosures or even the Form CRS developed via Reg BI, may be examples of providing high-level summary disclosures that are more easily (and more likely to be) read. But still create a burden to get the right disclosure information within documents so consumers gain the correct understanding of the advisor or broker’s role, and require that they are presented in a way that consumers have to actually engage with them. Those challenges are beyond the scope of this present study, but certainly need to be considered within the broader scope of understanding the various ways in which consumer clarity can be better promoted in the marketplace.

Titles, within the financial services industry, are absolutely designed to lend credibility to an individual and to influence prospective clients. Often, they ARE misleading. The simple solution (albeit an inflexible one) would be to use the regulatory terms for these financial professionals. A sales person with a Series 6 or 7 license is a Registered Representative. A fiduciary with a Series 65 is an Investment Adviser Representative. And, someone who sells insurance/annuities is an Insurance Agent. Collectively, firms could refer to a group of these individuals as Financial Professionals. Additionally, if you wanted to use the term “Financial Planner” then you would need to be an Investment Adviser Representative AND hold one of the following certifications/designations: CFP, ChFC, or PFS (and/or, maybe, others could be considered – such as CPWA or AWMA). Furthermore, a lot of confusion would be resolved by not permitting an individual to serve in two or three capacities (i.e., Registered Representative, Investment Adviser Representative, and Insurance Agent). The client will often not understand which “hat” the financial professional is wearing. Make the financial professional pick ONE (i.e., you can’t be BOTH a Registered Rep AND an IA-Rep). All the ambiguous designations are disallowed. Hence, clarity (at the expense of flexibility). Unfortunately, nothing is ever this easy. The industry will push back. There is simply too much money involved.

Interesting article. I’d be interested to know where wealth management or wealth manager would fall on the loyalty and competence chart.