Executive Summary

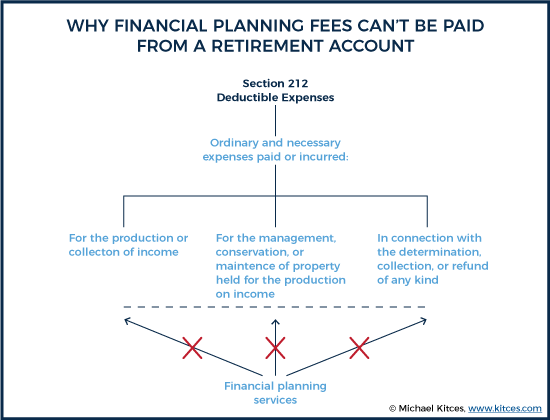

Acknowledging the need for and value of professional guidance in the long-term management of investment assets, the Internal Revenue Code allows investment advisory fees to be deducted as IRC Section 212 deductible expenses. Additionally, tax law also allows for Section 212 deductible expenses to be paid directly from the retirement account which accrued the expense, without fear of being treated as a taxable distribution (potentially subject to early withdrawal penalties) or a "prohibited transaction" (which could otherwise disqualify the entire account). However, while the benefits of investment advisory services are implicitly acknowledged in current tax law, the same is not true of financial planning services; unfortunately, financial planning fees cannot be paid from a retirement account without triggering the aforementioned adverse tax consequences... even though they may be equally (if not more) important in helping someone accomplish their long-term financial goals!

In this guest post, Derek Tharp – our new Research Associate at Kitces.com, and a Ph.D. candidate in the financial planning program at Kansas State University – delves into why it's problematic that financial planning fees can "only" be paid from after-tax accounts, the behavioral advantages of being able to pay financial planning fees from a retirement account instead, and explores how modifying current tax rules could allow more consumers to access financial advisors (while also creating better incentives for all advisors to be able to give advice that aligns with the clients' best interests).

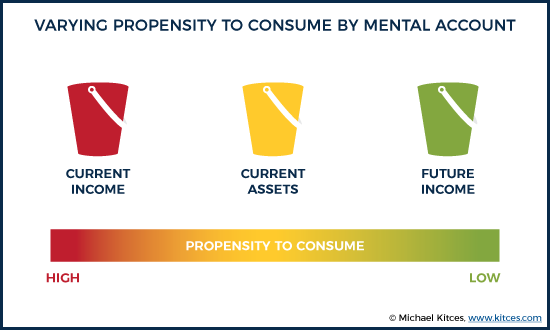

The reason why the source of financial planning fees matters is Shefrin and Thaler's mental accounting framework, which finds that consumption is broadly divided into three buckets: current income, current assets, and future income (or the assets that support future income). We know from behavioral research that people treat these "buckets" of money differently, where certain purchases are more or less likely to occur from one bucket versus another (depending on the nature of the expense). When it comes to financial planning services in particular, which is generally associated with "long-term" planning, mental accounting alignment suggests that consumers would be most comfortable paying such expenses from the "long-term" (i.e., future income) bucket. However, as noted earlier, paying financial planning fees from a retirement account isn't permitted... unless the financial planning services are bundled into a primarily-investment-management AUM fee, or a product commission paid with IRA dollars, which isn't always feasible or desirable.

There are alternative options that could be considered for giving consumers more control over their future income assets, though. One simple solution is to allow consumers to write checks or transfer funds to licensed financial advisors directly from their retirement accounts, and make the expense permissible (without adverse tax consequences) as long as it's paid to a (registered?) financial advisor. Other possibilities include giving consumers greater flexibility to roll money out of employer-sponsored retirement plans (similar to current HSA rules), or opening up paths for consumers to pay for services without rolling their funds out of employer-sponsored plans in the first place. Though, perhaps the simplest solution of all is to modify IRC Section 212 to recognize financial planning fees, which would both allow financial planning fees to be deductible when paid from an after-tax account, and also to be "safely" paid pre-tax from a traditional qualified account (perhaps with a complementary safe harbor under Section 4975 to make it clear that "comprehensive" financial planning fees are not prohibited transactions).

But ultimately, if the aim of tax policy is to facilitate better outcomes for consumers, it's worth acknowledging that the current framework unintentionally exhibits poor behavioral characteristics by limiting the ability of consumers to pay for long-term financial planning advice from accounts that are ear-marked for long-term goals (or forcing those financial planning fees to be bundled with AUM fees or product commissions that may not be practical or feasible in all situations)!

Current Rules On Paying Financial Planning Fees From A Retirement Account

While the rules are fairly straightforward for deducting investment advisory fees paid from a taxable account (treated as a Section 212 expense which is claimed as miscellaneous itemized deduction and limited to a 2%-of-AGI floor), there are more rules to consider when paying advisory fees from a retirement account.

Because ongoing investment advisory fees are Section 212 expenses under Treasury Regulation 1.404(a)-3(d), they can be paid directly from a retirement account without being treated as a taxable distribution or subject to early withdrawal penalties.

However, it is crucial to note that a retirement account only pay its own retirement-account-related expenses. Unlike a taxable account, which can pay advisory fees for a retirement account without being deemed a constructive contribution, retirement accounts that pay the fee of a taxable account would be treated at least as a taxable distribution (with potential early withdrawal penalties as well). At worst, though, such an IRA expenditure (on behalf of an outside account) could be treated as a “prohibited transaction” under IRC Section 408(e)(2) and IRC Section 4975, which can trigger a penalty tax of up to 100%, plus disqualify the retirement account altogether (i.e., be treated as though the entire retirement account has been fully distributed for tax purposes).

And the risk of paying non-IRA expenses with IRA dollars isn’t just limited to paying outside advisory fees. Paying financial planning fees would also be treated as a prohibited transaction, since they aren’t considered Section 212 expenses, because they don’t pertain directly to the collection of tax or the production of income. In the extreme, this can potentially even cause an issue with “bundled” investment advisory and financial planning fees, at least if the financial planning portion of the fee is a material component – again risking a prohibited transaction that incurs both the penalty tax and disqualifies the account. At best, even if it avoids prohibited transaction treatment, using IRA assets to pay a financial planning fee would be deemed a (taxable) distribution for the dollar amount of the fee.

Why It’s Behaviorally Appealing To Pay Financial Planning Fees From Retirement Accounts

One key insight of behavioral economics is that we aren’t fully rational when it comes to how we mentally account for our assets. In theory, household resources are fungible, and a dollar is a dollar, regardless of whether it came from the household’s most recent paycheck, a savings account, or a retirement account. However, real people don’t behave this way.

Shefrin and Thaler’s mental accounting framework finds that people tend to categorize their wealth across three broad buckets: current income, current assets, and future income (i.e., the assets that will support and fund future income). We have a tendency to treat these buckets differently, even if their financial value is fungible. Our propensity to consume is typically highest for current income (e.g., income and cash in a checking account), somewhat lower for current assets (e.g., investment accounts associated with shorter-term goals and less liquid assets such as home equity), and even lower yet for future income (e.g., dedicated retirement savings).

In addition to our general propensity to consume varying by mental account, we also apply both time and category constraints (i.e., budgets) within our various mental accounts . For instance, when deciding whether or not to buy coffee from a "current income” mental account, we may also ask ourselves whether doing so would violate category (e.g., only spend a certain amount on food) or time-based (e.g., only spend a certain amount this month) spending constraints. Yet, these categorical associations may vary across accounts. Buying coffee from "current income" may seem perfectly normal while buying coffee with funds from a 401(k) would likely violate our categorical associations for a "future income" account (at least for those in the accumulation stage).

Thus, one benefit of paying for financial planning services from a future income account is that the two are categorically connected, given that financial planning typically pertains to long-term planning (including future income in retirement itself). In contrast, paying $1,500 for a financial plan out of current income is more challenging, because it violates most of our categorical associations for monthly income, as financial planning isn’t something most think of as an “ordinary” monthly expense.

Another benefit of paying for financial planning from a future income account (e.g., retirement account) is that it can be a less salient transaction. By contrast, the traditional way of paying financial planning fees – from current income or assets – makes it more susceptible to the bottom dollar effect, increasing the potential psychological cost associated with the purchase. In other words, $1,500 financial planning fee “feels” like a bigger expense when we see it come out of our checking account than when it comes out of a future income account, and we notice it more when we have to actually write the check from our current income or assets. Which can be particularly problematic given that competition for our current income is fierce, and an intangible and hard to evaluate service like financial planning typically isn’t going to stack up well, as there are always more tangible goods and services which can provide more immediate satisfaction.

In fact, these dynamics go a long way to help explain how financial planning is typically paid for today – as an AUM fee from future income accounts. Planners focusing on hourly planning and retainers have seen limited adoption so far, likely because they rely on paying for financial planning from a current income mental account. Though, of course, consumers with little long-term savings may have no other choice.

Why It’s Problematic That Financial Planning Fees Can’t Be Paid From Retirement Accounts

As noted earlier, the AUM model has many great behavioral characteristics for those who have substantial assets), but a 1% AUM fee (and the minimums it often necessitates) unfortunately puts financial planning services out of reach for many. While companies like Schwab and Vanguard are demonstrating that a certain level of fiduciary advice can be provided to consumers with modest assets on an AUM basis, these models may not work for clients who want more local, personalized, one-on-one financial advice, especially with an emphasis on coaching and facilitating behavioral change in order to achieve financial goals. While not an intentional feature of our current tax laws, the inability for those with modest resources to purchase comprehensive financial planning services with their future income assets does, unfortunately, exacerbate inequality in access to financial advice.

For instance, a consumer with a $1,000,000 IRA has the ability to pay $10,000 or more annually for professional financial planning services from their future income assets. Yet, as discussed earlier, a consumer with a $10,000 IRA isn’t allowed to pay a one-time financial planning fee of $1,000, even though the less wealthy consumer may benefit as much, if not more, from financial planning services. That’s not to say that more is always better when it comes to purchasing financial services—it’s not—but the gap between what the wealthy and non-wealthy are allowed to spend from their future income buckets for financial advice is substantial.

Manageable retirement assets may be small or nonexistent because consumers are young and haven’t saved much yet, older and have struggled to make progress with their saving, or simply because their savings are all locked up in an employer-sponsored plan. But regardless of the reason, the only remaining option is for fees to be paid from current rather than future income, which, for reasons noted above, many consumers find unsatisfactory.

Further, these problems may persist regardless of household wealth or income. In a 2016 study of household spending based on data from a financial aggregation app, researchers found evidence that even households with sufficient savings and cash holdings live “hand-to-mouth”, consistent with the idea that these cash holdings have already been mentally earmarked for some other purpose (e.g., a cash cushion for unforeseen expenses or shocks to income). Therefore, even a household with a $20,000 cash reserve may feel like they can’t afford a $1,500 financial plan. They may feel this way because their current income is too tight to absorb a sudden $1,500 expense, and their $20,000 cash reserve is mentally earmarked for contingencies that would not include hiring a financial planner.

If the aim of public policy is to promote consumer and societal well-being, then we should ask ourselves how various policies may impede or facilitate those goals. Utilizing data from the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth, Michael Finke and Terrane K Martin Jr. found evidence of improved financial outcomes for those who work with a comprehensive financial advisor, though not those who work with an investment specialist. Studies by Morningstar and Vanguard have similarly affirmed the value of comprehensive financial planning advice (beyond “just” investment advice). If it is the case that working with a financial planner can improve financial outcomes, then it’s important to make it easy for consumers to pay for those services from the desired mental accounts.

The Irony Of Commissions Paid From Retirement Accounts

Perhaps to the chagrin of some fee-only advisors, it’s worth acknowledging that loaded A-share mutual funds actually have many positive behavioral characteristics as a means to pay for financial advice. And in some cases, A-shares have actually facilitated access to project-esque planning services paid for out of future income buckets, because clients who may not be willing to pay $1,500 for a financial planning project out of their current income may be willing to pay a 6% commission on a $25,000 retirement account. By contrast, if the only option was a levelized AUM fee, the advisor’s minimum might have to be higher than that $25,000 account, limiting access to advice for the consumer who can’t pay the financial planning fee from current income.

In other words, the claim that A-shares provide a means to effectively serving certain client segments is not entirely dubious. However, the reason why A-shares are effective is not because inherently conflicted product sales are needed to reach these clients, but rather because A-shares provide the only means for clients with modest resources to pay for services with their future income assets. Nonetheless, the fact remains that some advisors may currently feel “forced” to rely on commissions, just to serve a clientele who can only afford financial planning from retirement accounts, and commissions are the only way to make those accounts “liquid” enough to pay the fee!

Clearly, this is not an ideal mechanism to facilitate the payment for advice, as the conflicts of interest introduced through the sale of mutual funds and other investments with large upfront commissions are problematic (and particularly when those who sell the investments don't actually intend to provide much financial advice anyway). On the other hand, what is often vilified as an “unreasonable” commission for a standalone sale (e.g., 5-6% front-end load) might, in fact, be very “reasonable” compensation for broader financial planning services that were actually delivered and paid for by that commission.

Giving Consumers More Control Over Their Future Income Bucket

Given these dynamics, arguably it’s time to revisit the control and flexibility that consumers are provided over their future income buckets, as “forcing” compensation through commissions just to pay for advice from a retirement account is not ideal – and particularly for those who need substantial advice and have very modest retirement accounts.

Example. A young graduate has accumulated $1,000 in a 401(k), but is buried in student loan debt and about to switch jobs. He would like to get a basic financial plan for $1,000, but doesn’t have the available cash in his checking accout, and thus would “have to” use his retirement account to pay for advice.

Arguably, paying a planning fee equal to 100% of a modest account balance may very well be a better use of those funds than parking it in an S&P 500 index fund for the next 40 years. Getting out of debt, learning to budget, and developing good financial skills at a young age are all tremendously valuable. Sure, that $1,000 may turn into $20,000 or so by retirement, but establishing a solid plan early in life is likely worth a lot more than $20,000 come retirement. This is particularly true if a financial planner can help meaningfully change an individual's income and career trajectory. Unfortunately, though, trying to use the funds in a retirement account would trigger taxes and an early withdrawal penalty at best, or a prohibited transaction at worst!

Fortunately, there are many ways that consumers could be given more control over their future income buckets. One simple solution is to allow consumers to write checks or transfer funds to licensed financial advisors from their retirement accounts.

From a regulatory perspective, this would necessitate clarifying and substantiating which financial advisors are actually providing financial planning advice and which are simply making investment recommendations or selling investment products (which is arguably an important clarification for consumers, anyway!).

Another option to facilitate paying for financial advice from retirement accounts is to give consumers greater flexibility to roll money out of employer-sponsored retirement plans. This actually has the dual benefit of making employer-sponsored plans compete harder to maintain participant dollars, while also providing flexibility for those who feel they may benefit from working more directly with a professional. An effective alternative may be a system that operates more similar to how Health Savings Accounts (HSAs) work today, where most employees stay with the employer selected plan, but flexibility does exist, including the flexibility to transfer the assets and hire an advisor.

Other avenues for a financial advisor to be compensated through employer-sponsored plans are an option as well. For instance, employer-sponsored plans could be permitted to add portals which allow advisors to access, manage, and be paid for their services – including the non-taxable (and non-prohibited) withdrawal of a financial planning fee without the need for any rollover. Some may object that advisors have little opportunity to add investment alpha through this type of arrangement, which may be true, but as noted above, the primary benefit would be allowing consumers to utilize their future income resources to pay for financial planning services such as behavioral coaching, tax planning, and other higher impact value-adding services that advisors provide.

Though, perhaps the simplest approach would simply be to modify IRC Section 212 to recognize financial planning fees, along with fees for tax preparation and the management of property, which would allow financial planning fees to be deductible when paid from an after-tax account and to be paid pre-tax from a retirement account (with perhaps a complementary safe harbor under the Section 4975 prohibited transaction rules to make it clear that a “comprehensive” financial planning fee that goes beyond the retirement account doesn’t disqualify the account).

Ways To Guard Against Abuse

A skeptical reader may suspect that all of this talk about mental accounting is just an attempt to rationalize new revenue opportunities for the financial planning industry. It’s fair to acknowledge that what economists refer to as “rent-seeking” is a legitimate concern (e.g., industry members seeking regulatory policies that further their interests at the expense of consumers or competing firms), but it shouldn’t be assumed that what’s good for advisors is necessarily bad for consumers. With some safeguards in place, it is possible that both advisors and consumers could benefit from consumer ability to pay financial planning fees from retirement accounts.

Time Or Dollar Limits On Planning Fees Paid From Retirement Accounts

Planning-related “churning” – charging a high volume of ‘unnecessary’ fees for superfluous advice – is one potential concern that could arise from increased ability to pay planning fees from a retirement account.

To guard against this, time- or dollar-based restrictions could be put in place regarding distributions to pay planning fees. For instance, a consumer may be limited to one project engagement over a certain dollar limit every 12-months. Additionally, an annual fee limit for distributions paid towards retainers or other ongoing engagements could be put in place, akin to the “maximum” level of deduction or credit applied to many other tax preferences under the Internal Revenue Code. However, to avoid the problem of cutting those without substantial assets off from using their future income assets to engage a professional (as is currently the case with AUM), these guidelines would ideally provide reasonable flexibility.

For instance, instead of just a flat dollar amount or percentage-based limits, the rules could establish some fixed guidelines as well as more dynamic ones. For instance, annual distributions could be limited to the greater of $5,000 or 2% of assets. A $5,000 plan should be more than enough to get most average consumers a solid financial plan, while those who need more than $5,000 worth of planning would likely be eligible for higher limits under the 2% of assets guideline.

Interestingly, A-shares again provide a real-world example of some attractive compensation dynamics. The structure of A-share compensation implicitly acknowledges that higher percentage based fees are reasonable for smaller accounts, reasonable fees should decline as a percentage of the account as the account gets larger (as A-share typically have breakpoints at higher asset levels), and larger one-time fees should be subject to greater scrutiny for transactions that are excessive in frequency.

Annual Fee Disclosure And Summary

Notably, one of the biggest potential risks of making it easier for retirement accounts to pay financial planning fees is that, similar to commissions and even some AUM fees, some consumers may take on high-cost providers without fully realizing what they’re actually paying.

Richard Thaler’s “Smart Disclosure” framework provides an opportunity to make disclosures more meaningful and help consumers become more aware of what they are paying. If consumers received a standardized summary of fees at the end of the year - both for investment management, and financial planning – they could use these fee disclosures to evaluate what they are paying relative to the fees experienced by other consumers. Ideally something similar to Thaler’s “Choice Engines” would exist to help consumers make use of their standardized disclosure and evaluate alternatives.

Ultimately, the reality is that there is a lot of room for improvement in addressing the behavioral dynamics associated with the mental accounting of paying for financial planning services.

Our current tax framework allows advisors to be compensated for few of the services found to be truly value adding – like financial planning – yet explicitly permits compensation for a service (investment management) that is rapidly being commoditized and has not been shown to add value. Notably, in practice, most advisors actually bundle services in a way that confounds what they get paid for and what they actually do for clients, making any clear delineation of what consumers are actually valuing and paying for difficult, but at some point, the IRS may catch up to industry practices and realize there is a significant opportunity to enhance consumer well-being by allowing consumers to use their funds to pay for services beyond investment management!

Facilitating healthy financial behaviors not only benefits consumers directly but society more generally. By adopting more innovative tax rules to allow retirement accounts to pay for both investment management and financial planning services, regulators and policy makers can better incentivize financial advisors, while also giving consumers more opportunities to enhance their long-term financial well-being in a manner that aligns with their natural inclinations for financial decision-making.

So what do you think? Should consumers be able to pay financial planning fees from retirement accounts? Have A-share mutual funds played a historically underappreciated role in facilitating the payment of fees for financial planning services from future income mental accounts? What safeguards would be needed if consumers were given the ability to pay financial planning fees from retirement accounts? Please share your thoughts in the comments below!

Your solution seems like to alleviate the financial advisor of his/her responsibility to create innovative products and services and justify their value to potential clients. If consumers won’t pay for financial planning, then the service is wrong, the price is too high, or the value isn’t clear.

Hypothetically, if you had a $5 million revenue company and balked at a $100,000 contract for payroll services but accepted a 2% of revenue charge, your evaluation of the service’s value did not change, you just can’t equate 2% with $100,000. While this cognitive bias can sometimes be used to trick people into good decisions (e.g., investing for retirement), it doesn’t change the fact that people are moved towards decisions they otherwise wouldn’t make if they had an apples to apples comparison of cost to perceived value.

If consumers wouldn’t purchase a given product or service if they understood the value vs. price on a simple invoice, then regulating bodies should take no action to allow providers to further obfuscate the price or allow consumers to pay it with dollars traditionally prohibited from making similar purchases.

If the low-end consumer won’t (or can’t) buy financial advice because the perceived value is less than the price, then the market should create new products or services or at least better communicate the value of existing products and services, not lobby for access to a larger pool of consumer funding.

Again, this seems like more of a sales problem for financial advisors than a problem for consumers.

Finance,

To the contrary, the whole point of this discussion is to drive LESS obfuscation in how financial advice is priced to consumers.

As it stands now, consumers whose assets are in retirement accounts can only “buy” financial advice with those assets by turning them over to manage, or putting them into a product. There’s no option to unbundle and simply use (less of) the money to buy just financial advice.

The kind of change being advocated here would make it easier for consumers to buy what they want, more transparently and more flexibly.

And again, the problem for many consumer segments is that if you “ban” them from buying advice with their retirement accounts, they can’t buy it at all, because that’s the only place they HAVE dollars to spend. That’s not a value perception problem. That’s a tax liquidity problem, artificially created by tax policy, that prevents consumers from using long-term retirement assets to pay for long-term retirement advice.

– Michael

Point taken, thank you for your response. I overlooked the liquidity issue and the author’s solutions provide multiple workable solutions to that challenge.

Should all services provided by a financial advisor be eligible for payment with retirement funds?

Given the nature of how bundled commission or AUM payments are taxed, any/all services already ARE eligible for payment with retirement funds, as it exists today.

The problem is that it’s ONLY available in bundled form, which not every consumer actually wants. :/

In essence:

Tax policy today: Buy any financial advice you want with your retirement dollars, as long as you buy it as a free throw-in to some OTHER product or (managed account) investment service.

Proposed tax policy: Let people buy what they want separately, particularly if they just want to buy advice and not an accompanying product or managed account.

– Michael

Michael,

I agree that it is unfortunate consumers are forced to purchase planning as a bundled service and I hope that IRC 212 is amended.

With that being said, I understand that consumers cannot simply withdraw a specific dollar amount (upfront fee or retainer), but is it possible to manipulate your AUM fee based on the services you provide within your Adv?

E.g.

0.25% All Asset mgt only

1.00% Comprehensive planning

Client can choose to pay for asset mgt or both.

As an advisor writing a new Adv, I’m just confused how advisor’s can legally waive their retainer fees for financial planning when clients have over $100k in their account yet the IRS still intrupets the AUM fee as “ordinary & necessary”.

Thank you for all that you do!!

-Colin

I’ve always thought it inherently unfair that financial product developers/promoters get to deduct all the expenses they incur as they develop and promote ever-increasingly complex (and often dubious) products, yet individuals are rarely able to deduct all of the costs that they incur to get competent advice to help/protect them. What’s fair about that?

I gave up on trying to understand this some years ago. However, my investment advisor never itemized the fees he was taking form my tax-advantaged accounts. I could only find them by looking at my Schwab statements (Schwab was the custodian).

To that extent, I feel the advisor was attempting to hide the true costs from me. No statements from him, no tax forms, …

I was also surprised to find another advisor who claimed that the fees taken from tax-advantaged accounts were not taxable, but they counted towards RMDs. That seemed odd, though I did not go down that road.