Executive Summary

According to the American Psychological Association, nearly 2/3 of Americans rate money and work as significant sources of stress in their lives. And because money is such a common source of stress, as well as a difficult or uncomfortable topic for many to discuss, we often tend to seek ways to minimize consciously thinking of how we use money (such as by opting for cash-free forms of payment). But people who don’t retain at least some awareness of their spending may subconsciously use other people's behavior as a guide to making money decisions, instead of consciously making choices based on their own personal values and priorities.

In this guest post, Derek Hagen – Founder of Money Health Solutions, a financial therapy and financial life planning firm – discusses how financial advisors can develop a Financial Purpose Statement for their clients to use by helping them examine their relationship with money and identifying their most meaningful goals. Furthermore, he explains how the Financial Purpose Statement can guide clients to live their (financial) lives with deliberation, ultimately helping them to (re-)align their behavior with what matters most to them!

At its core, a Financial Purpose Statement consists of a simple statement that crystallizes the purpose of money in the client’s life. To develop a relevant Financial Purpose Statement, an individual must reflect deeply on the kind of life they would like to have and the person they want to be. Advisors have several tools they can use to help clients examine these ideas and identify their most meaningful values. Some of these include the Klontz/Kahler/Klontz Life Aspirations exercise, which helps individuals consider their ideal life; the Miller/Rollnick Values Cards, which create a systematic process to prioritize meaningful personal values; and George Kinder’s Life Planning Questions, which aim to reveal important life priorities by asking clients to contemplate their own mortality.

Ultimately, Financial Purpose Statements can distill an individual’s values and priorities into an easily accessible reminder that can help them make spending decisions in alignment with what really matters most to them. And by helping clients to develop their own Financial Purpose Statements, advisors can encourage their clients to get clear on what their most important priorities are and guide them toward making the right financial decisions, helping clients live happier lives and achieve their most important goals with clarity and intention!

The Stress Of Managing Money: A Lack Of Spending Awareness And Intentional Living?

In her book The Top Five Regrets of the Dying, former palliative caregiver Bronnie Ware writes about some of the most common regrets of people lying on their deathbeds. Of these, the top regret is living the life that others expected of them, rather than being true to themselves. Followed closely by working too hard.

In her book The Top Five Regrets of the Dying, former palliative caregiver Bronnie Ware writes about some of the most common regrets of people lying on their deathbeds. Of these, the top regret is living the life that others expected of them, rather than being true to themselves. Followed closely by working too hard.

For financial advisors who want to help their clients better understand the role that money plays in their lives, a Financial Purpose Statement can be a valuable tool to show clients how to realign their use of money with what's really important to them. In other words, it helps clients use money more intentionally, thereby reducing money stress (and ideally enhancing their overall wellbeing!).

Creating a Financial Purpose Statement can help us to use money to live our lives (more) intentionally.

Modern Payment Systems Have Made It Easier To Spend Without Intention

The "pain of paying” refers to the discomfort or displeasure we tend to feel when we spend money, as we can associate the act of spending with the idea that we are losing something valuable, even though we are (hopefully) getting something equivalent in value in return.

For example, when we use cash, we must physically count the amount of money needed for the transaction, and then actually hand it over to someone, which makes us very aware not just of the fact that we are spending money, but also of exactly how much we are parting with. And because of this heightened awareness of our spending, we experience the pain of paying more so than with other forms of payment. The higher the transaction amount, the more severe the pain of paying we might experience.

Similarly, when we write a check (or, rather, when we used to write checks), we have to write the amount of the transaction at least twice – once in numbers, and then again spelled out in words. And those who balance their checkbook will write it a third time in their check register. Having to write the amount of the transaction two or three times can also induce the pain of paying because it makes us so much more aware of exactly how much we were spending.

However, with many modern forms of payment, the pain of paying often doesn't exist. We send payments to one another with our phones. We log into an account to link a payment method so we don't have to think about paying when we make transactions. If we go into a store, we tap our card to a reader, and often don't even bother to get a (physical paper) receipt. Because there aren’t as many reminders of how we spend our money with these modern payment methods, we tend to experience the pain of paying much less.

Furthermore, because humans dislike painful experiences, we tend to do more of the things that don't have pain associated with them. And because less ‘pain of paying’ can be associated with some of the more modern forms of payment, many of us have readily opted to favor those payment methods… which means that the pain of more spending-conscious modes of payment, such as paying in cash or with physical checks, isn’t there to help us stay aware of our spending!

Yet, without an awareness of our spending, it’s sheerly coincidental – at best – if that spending effectively aligns with our values (beyond perhaps some short-term desires). Which means ultimately, the ease of modern payment systems is paving a path to spending without intention.

The (Adverse) Consequences Of Spending Without Intention: Social Comparison And Relative Deprivation

The reason that spending without intention is so concerning is that, ultimately, something has to guide our financial decisions in the moment. Which means if we’re not aware of our spending (to ensure it’s aligned in the first place), we will tend to look to other cues in our environment about what spending is appropriate or not. And as we often tend to behave similar to ‘herd animals’, our most common point of comparison – in the absence of spending awareness to align to our own values – will be looking to what everyone else is doing.

As noted earlier, humans dislike painful experiences and will often act to avoid them. So, when someone feels financial stress, they may be tempted to mimic someone else’s behavior if that person appears to be stress-free. The caveat, though, is that because money tends to be a taboo topic for many people, financial stress is difficult (if not impossible) to assess by appearances alone.

In other words, sometimes the person who appears to be living a carefree life with a beautiful house, a beautiful car, and a smile on their face is, in reality, up to their eyeballs in debt and simply better at hiding their financial stress.

At the same time, the problem with spending behavior driven by social comparison is that it can result in feelings of relative deprivation when one can’t afford the same things that other people have, even though the reasons for wanting those things may not be apparent, and the person who does have those things might actually be experiencing overwhelming levels of financial stress. Furthermore, the person influenced by social comparison, who feels deprived, may already have all they actually really need!

Spending driven by social behavior can, in turn, lead to ‘conspicuous consumption’ – spending in a way that signals status so that other people will notice – effectively using “status with the herd” as the basis for spending decisions, instead of aligning spending habits with more important personal values. This is more likely to happen when we aren’t fully aware of our spending and other financial decisions.

This tendency to develop spending habits based on conspicuous consumption is particularly common for maximizers, who tend to find themselves on goal treadmills, in an endless pursuit of obtaining and achieving more, but with no real purpose other than to surpass their last achievement. As it is with running on a treadmill, when there’s no clear endpoint to the race, it may not be obvious when we’ve arrived at our destination and when it’s time to step off.

We Regret Not Living Up To The Values We Never Got Clear About Earlier

Author Bronnie Ware points out that one of the top regrets of people on their deathbeds is that they didn't live a life true to themselves – instead, they lived a life that others expected of them.

In his book The Happiness Hypothesis, Jonathan Haidt writes:

In his book The Happiness Hypothesis, Jonathan Haidt writes:

...People would be happier and healthier if they took more time off and spent it with their family and friends... People would be happier if they reduced their commuting time, even if it meant living in smaller houses... People would be happier and healthier if they took longer vacations, even if that meant earning less... People would be happier, and in the long run wealthier, if they bought basic, functional appliances, automobiles, and wristwatches, and invested the money they saved for future consumption.

He goes on to say that most people spend everything that they have (or more) on things they don't need.

In essence, a person who pursues goals and makes financial decisions that are based on other peoples' values, instead of acting on their own values, can result in living a life that the person may think they're supposed to live (as determined by others), rather than one that would actually be more likely to make them happy. This misalignment with one’s own values can lead to uncomfortable stress (and sometimes even a midlife crisis or end-of-life regret).

Many financial advisors may have worked with successful clients who don't seem genuinely happy. For example, a client who expressed that their primary goal was to become the head of his company was devastated when the choice cost him his family. Another client whose goal was to become a millionaire by age 40 ended up regretting their decision when they realized the serious toll it took on their health. Or a client who worked tirelessly for decades at a job he hated so he could retire ‘early’ at age 62, who was disappointed by the lost opportunity to enjoy his youth.

Advisors with clients like these have an opportunity not only to help them identify their most important values, but also to help them develop the key behaviors that will support those values. Ultimately, financial advisors can have a tremendous impact by helping their clients implement strategies that align their spending and other financial decisions with their own personal values.

A Financial Purpose Statement Helps Clients To Identify Meaningful Goals And To Cultivate Financial Awareness

In his book The One-Page Financial Plan, author Carl Richards recommends finding out why money is important to clients. He says that figuring out why money is important is the first step towards making financial decisions that are in line with the client's values.

In his book The One-Page Financial Plan, author Carl Richards recommends finding out why money is important to clients. He says that figuring out why money is important is the first step towards making financial decisions that are in line with the client's values.

Another book, Mind Over Money, by Financial Psychology researchers Dr. Brad Klontz and Dr. Ted Klontz, builds on the importance of contemplating the significance of money and identifying values. By referring to “money mantras” written on notecards, individuals can practice deliberate money mindfulness by consciously countering automatic financial beliefs, known as Money Scripts, that might otherwise interfere with what’s truly important to them. By keeping the notecard and reviewing their money mantra as needed, they can see it, remember it, and become more aware of (and overcome) the negative impact that Money Scripts can have on their choices.

Financial advisors can effectively combine these two ideas of the one-page financial plan and money mantra with a Financial Purpose Statement, which can help clients use money in a way that supports the life they want, and one that they'd be happy to look back on.

A Financial Purpose Statement is created through a set of exercises designed to help clients get clear about what is important to them, and how they can use money in alignment with their values. It defines what money needs to do for the client.

Financial Purpose Statements are simple documents that can be carried with the client at all times in their purse or wallet, where they can look at the card when making spending decisions. Others may choose to tack it up near their home computers, and others may even use them more metaphorically, creating a simple enough statement that they can remember and recall when spending decisions need to be made.

However a client chooses to use their Financial Purpose Statement, it will serve as a beacon or North Star to help guide their financial decisions in the right direction by encouraging them to slow down, taking the time and space they need to make choices with awareness and intention.

A Financial Purpose Statement Should Help Clients View Money As A Tool to Achieve Their Goals, And Not A Goal Itself

In his book Happiness Studies, Tal Ben-Shahar breaks the elements of happiness down into five component parts, using the acronym SPIRE:

In his book Happiness Studies, Tal Ben-Shahar breaks the elements of happiness down into five component parts, using the acronym SPIRE:

- Spiritual wellbeing involves being in the present moment and having a sense of purpose.

- Physical wellbeing represents not only basic needs, rest, exercise, and nutrition, but also attending to the mind-body connection.

- Intellectual wellbeing represents keeping our minds active, solving interesting problems, and being curious.

- Relational wellbeing represents cultivating our interpersonal relationships and having a healthy relationship with ourselves.

- Emotional wellbeing represents not only cultivating positive emotions and coping with negative emotions, but also accepting all emotions as they arise and giving ourselves permission to be human.

Notably, financial wellbeing is not on the list of components that make up happiness, even though it is very common for people to think that money is an end goal.

Many advisors have had clients who believe this. These are the clients who want to be a millionaire by age 40, or who will retire only once they have $3 million. It is the person that will leave his job when his portfolio generates $75,000 a year, or the person that wants to be financially independent by age 35. Less conspicuous is the client who wants to climb the corporate ladder to move her family to a wealthier neighborhood, even when they feel safe and are happy in their current lifestyle.

For all of these clients, the common theme is that money or financial success is considered the primary goal.

While it can be tempting to think financial wellbeing should be included as a component of happiness – because money is such an important part of our lives, and it is common to have financial goals as a part of the financial plan – the unique quality of each of the SPIRE elements is that they all represent ends, as contrasted with money and financial wellbeing, which are not ends themselves.

Instead, money serves as a means to these ends. Money can be used to support and help achieve the SPIRE elements of happiness. In other words, when it comes to designing Financial Purpose Statements, the goal is to get to the underlying elements of what will really bring happiness and wellbeing (and then the financial plan can figure out how the money will fulfill those pursuits).

Or viewed another way, for those clients who state that they have ‘money goals’, the important questions to raise with these clients are: What happens when they achieve their money goals? What will they do at age 40 once they become a millionaire? What does retirement look like when they have $3 million (and could that actually be achieved by the client with ‘just’ $2.5 million, or just $2 million instead, shaving years off their goal)? Why does the client need $75,000 of generated income, and why did they choose age 35?

A Financial Purpose Statement, including the process of creating it, helps clients answer these questions, and to detach themselves from the idea that money is the goal.

A Financial Purpose Statement Creates Mindfulness And Awareness About Our Financial Lives

Jon Kabat-Zinn, author of Wherever You Go, There You Are, defines mindfulness as paying attention to the present moment without judgment and without trying to change how it is. Teaching clients to think about their financial decisions through the lens of their Financial Purpose Statement helps slow down their decision-making process by making it a more mindful process. This act of slowing down enables clients to assess their financial decisions more carefully, and to recognize when their decisions may reflect social comparison or conspicuous consumption, rather than being actions that are in alignment with their true personal values.

Jon Kabat-Zinn, author of Wherever You Go, There You Are, defines mindfulness as paying attention to the present moment without judgment and without trying to change how it is. Teaching clients to think about their financial decisions through the lens of their Financial Purpose Statement helps slow down their decision-making process by making it a more mindful process. This act of slowing down enables clients to assess their financial decisions more carefully, and to recognize when their decisions may reflect social comparison or conspicuous consumption, rather than being actions that are in alignment with their true personal values.

Meditation teacher Joseph Goldstein often advises his students to know what they're doing; to sit and know they're sitting, or to breathe and know they are breathing. Similarly, living with financial mindfulness and awareness means knowing what's going on underneath the hood of our financial lives. It involves reintroducing the ‘pain of paying’ so that it becomes more financially salient and helps us become more aware of our spending.

This occurs through the lens of the Financial Purpose Statement, which provides a means to help clients make financial decisions with awareness and, thus, with intention.

How To Create A Financial Purpose Statement To Help Clients Understand Their Priorities

Because Financial Purpose Statements tend to be short, they can seem simplistic. Beneath the seeming simplicity, though, is a powerful way to tap into what motivates clients, what they want out of life, and the kind of people they want to be.

Before crafting a Financial Purpose Statement with clients, it's helpful for advisors to prime clients to think about their most important values, aspirations, and priorities. Guiding clients through exercises like these helps them pause and contemplate these themes in their lives, which is valuable as many have never thought about their money in this way before. They may still be hung up on what they think they’re supposed to do (as determined by what others think, versus what is most personally important to them), or they haven’t ever thought about their own priorities as they relate to financial goals.

Exercises To Help Clients Consider Their Goals And Values

Below are some priming exercises and thought experiments that can help clients determine their priorities, so that they can craft their Financial Purpose Statement. These are simply suggestions; advisors don’t have to use all of them. In fact, only the exercises with which they feel comfortable ought to be used, as many exercises can induce a variety of emotions and feelings, including excitement, motivation, fear, sadness, and even death anxiety (such as the Kinder questions, the Life In Weeks exercise, or the Tape Measure exercise).

It may take several meetings to go over the exercises. That's okay; it's better to take it slow than to rush through them. However, spacing these exercises out too far apart runs the risk of earlier discussions becoming stale in the clients' minds. Thus, advisors can be most helpful by determining the pacing for clients that will give them enough time to thoughtfully reflect on these exercises, but that will still maintain the momentum of the discussions. There’s no hard and fast rule, but trying to get through the exercises within a month, give or take a week, will help keep the exercises fresh in the client’s mind.

Life Aspirations Exercise

In their book Facilitating Financial Health, Brad Klontz, Rick Kahler, and Ted Klontz offer an exercise called the “Life Aspirations” exercise (which also shows up in an earlier book, Conscious Finance by Rick Kahler and Kathleen Fox). With this exercise, clients are asked to imagine a world with no financial restrictions, time restrictions, talent restrictions, and reality-based restrictions. Clients write down what they would do in such a world.

In their book Facilitating Financial Health, Brad Klontz, Rick Kahler, and Ted Klontz offer an exercise called the “Life Aspirations” exercise (which also shows up in an earlier book, Conscious Finance by Rick Kahler and Kathleen Fox). With this exercise, clients are asked to imagine a world with no financial restrictions, time restrictions, talent restrictions, and reality-based restrictions. Clients write down what they would do in such a world.

It's not always easy for clients to imagine this hypothetical world, so it might be helpful to provide some examples meant to prime them to think big (so they don’t remain anchored in any way to the limitations of their current life). Some examples might be to move to the moon, to live in every country on earth, to learn every language, to own a sports team, to cure cancer, or to invent a new species of tomato.

After clients come up with several examples of their own, the advisor can ask them about the reasons they chose those answers. Assuming they could achieve whatever they wrote down, ask them what would be desirable or important about that accomplishment.

These answers should follow the form "to be ______", but will be different for everyone, even with the same aspiration. For example, three people might say they want to move to the moon. For the first client, that might be important because she wants to be an adventurer. For a second client, that might be important because he wants to be well-known. For a third client, that might be important because she wants to be away from people.

After clients go through this exercise, they'll have a list of "to be" statements that give insight into their values, and that help indicate the kind of people they want to be.

Exploring Personal Values With The Values Card Sort

We can help clients discover their personal values (i.e., beliefs about what they find important) in several ways. Some of them are quick and fun, like asking a client what kind of tattoo they would get if they were offered a tattoo that represented the kind of life they wanted to be reminded to live. Others take a little more time and require more introspection. There are several “Values Worksheets” provided by positivepsychology.com that can be helpful to advisors when guiding their clients through an exploration of their values.

William Miller and Stephen Rollnick offer one particularly useful exercise called the Values Card Sort in their book Motivational Interviewing (available to download from the Motivational Interviewing Network Of Trainers website). With the Values Card Sort, advisors present the client with about 100 values, one at a time, and ask them to rank each value based on their initial reaction. Value cards can be printed and laminated, or an electronic version can be created using form software (e.g., Google Forms). Interested advisors can order a physical deck of cards from Money Health Solutions.

William Miller and Stephen Rollnick offer one particularly useful exercise called the Values Card Sort in their book Motivational Interviewing (available to download from the Motivational Interviewing Network Of Trainers website). With the Values Card Sort, advisors present the client with about 100 values, one at a time, and ask them to rank each value based on their initial reaction. Value cards can be printed and laminated, or an electronic version can be created using form software (e.g., Google Forms). Interested advisors can order a physical deck of cards from Money Health Solutions.

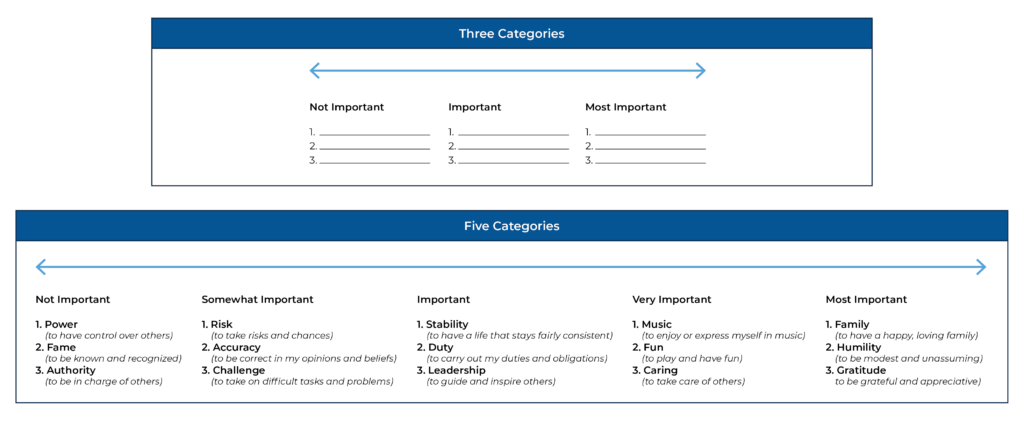

To rank the values, a series of either three or five categories can be presented to the client, as follows:

Whichever way is chosen, it is important to urge clients not to censor themselves and to assure them that there are no right or wrong ways to rank each value. The intent is not for them to rank some values highly because they think they are supposed to, or to feel embarrassed about how they want to rank other values lower.

Clients can go over their ranked list when they're done and change their minds if they want to. For the first pass, though, they should be encouraged to rank the values according to their instincts. Advisors can take this exercise as far as they want to. For example, clients can be asked to get their list down to their top five or ten values, so they prioritize only their highest-ranking values.

Then, depending on what feels most comfortable, advisors can choose to have a conversation with clients about the exercise, or to ask them to journal about what it is about their top values that are important to them. This will help the clients understand the kinds of things that are important to them.

George Kinder’s Three Life Planning Questions

George Kinder, known as the “father” of life planning, developed an exercise involving the following three questions for advisors to ask their clients and help them explore what’s most important to them.

Question 1: Design Your Life

I want you to imagine that you are financially secure, that you have enough money to take care of your needs, now and in the future. The question is, how would you live your life? What would you do with the money? Would you change anything? Let yourself go. Don’t hold back your dreams. Describe a life that is complete, that is richly yours.

Question 2: You Have Less Time

This time, you visit your doctor, who tells you that you have five to ten years left to live. The good part is that you won’t ever feel sick. The bad news is that you will have no notice of the moment of your death. What will you do in the time you have remaining to live? Will you change your life, and how will you do it?

Question 3: Today’s The Day

This time, your doctor shocks you with the news that you have only one day left to live. Notice what feelings arise as you confront your very real mortality. Ask yourself: What dreams will be left unfulfilled? What do I wish I had finished or had been? What do I wish I had done?

These questions are a great way to help clients uncover priorities that may not be getting the attention they should be. This is especially true for questions two and three.

Life-In-Perspective Tools

Helping clients put their lives in perspective can shine a light on areas of their lives that may not be getting enough attention, or other areas of their life that are getting too much attention. Some people who have had a near-death experience have been faced with this level of clarity, reporting a significant change in priorities after their experience. These situations can be used as powerful examples to remind clients that they don't have unlimited time, which can help them focus (or refocus) their lives on what's most important to them.

There are many tools that help clients put their lives in perspective without having to face a near-death experience. Tim Urban, founder of the blog Wait But Why, created an exercise to help individuals see how short life is, and to help shine a light on areas where they may want to consider changing, in order to live more enjoyable and fulfilling lives.

Specifically, Urban created a powerful visual Life Calendar tool that shows one box for every week of a person's life with a 90-year life expectancy.

The idea is to fill in the boxes for those weeks that clients have already lived. This same exercise can be used with months or years, as well. Then advisors can ask clients to reflect on the life they've lived, and how they want to spend the rest of the boxes that aren't yet filled in.

Ted Klontz and Brad Klontz, who founded the Financial Psychology Institute, created a similar exercise using a measuring tape. With the Tape Measure exercise, clients are given a flexible sewing measuring tape (if working with a married client couple, one tape measure is given to each person). It should be 120 inches long (or 120 centimeters – we don’t use the units, just the numbers). Have the client take a pair of scissors and cut the tape at their current age. Have them reflect on the life they’ve lived while they hold their lives in their hands. After they’ve reflected, have them throw that piece of tape (representing the life they’ve lived) to the floor, signifying their acknowledgment that the past is over and can’t be changed. Ask about any thoughts or feelings that arose after throwing this piece away. Next, have the client cut the tape at what they think their life expectancy will be. This leaves them with the rest of their life. Have them reflect on how they want to “spend the rest of their tape”.

All of these life-in-perspective exercises are powerful tools that have the potential to invoke many different emotions ranging from excitement to fear. Accordingly, to prepare for some of the strong emotions that can arise, it’s recommended that advisors do this exercise for themselves before using it with clients.

Reflecting On Regrets

Asking clients to reflect on some common regrets other people have as they look back on their lives can help them identify potential regrets of their own, and can also help them recognize that they still have time to do something now to avoid them in the future.

Bronnie Ware writes that the top five regrets of the dying are:

- They lived the lives others expected of them rather than being true to themselves.

- They worked too hard.

- They didn't tell others how they truly felt.

- They didn't stay in touch with their friends.

- They didn't allow themselves to be happier.

The most important thing for advisors considering which exercises to use is their own comfort level. If advisors don't feel comfortable using a particular exercise with clients, clients will notice that and may not be comfortable fully engaging in the discussion.

Helping Clients Draft Their Financial Purpose Statement

The exercise of crafting the Financial Purpose Statement is simple. After clients have had a chance to contemplate their experiences facilitated through the previous exercises, advisors can ask them to create their own Financial Purpose Statement by completing the following sentence:

Money's purpose in my life (our lives) is to ___________.

That's it. It's simple, yet profound.

It's best to assign this as homework so that clients can work it and rework it as many times as they need to, with the ultimate aim for clients to come up with something that will be genuine and easy to remember. For couples, advisors can have each partner draft their own Financial Purpose Statement, and then help them to create a combined statement.

In their book Find Your Why, authors Simon Sinek, David Mead, and Peter Docker advise coming up with a short, powerful “Why” statement, which can be considered similar to a Financial Purpose Statement. They prefer a shorter statement to a longer statement because it's easier to remember, similar to money mantras that Ted and Brad Klontz write about in Mind Over Money.

In their book Find Your Why, authors Simon Sinek, David Mead, and Peter Docker advise coming up with a short, powerful “Why” statement, which can be considered similar to a Financial Purpose Statement. They prefer a shorter statement to a longer statement because it's easier to remember, similar to money mantras that Ted and Brad Klontz write about in Mind Over Money.

Although one could make the argument that shorter is better, that need not be the case. While some clients will be able to distill this down to 1–3 sentences, others will write a paragraph. These are all perfectly fine because the client is drafting the statement for their own benefit. If their Financial Purpose Statement is written in their own words, it is more likely to resonate with them.

Below are some real-life examples (slightly changed for anonymity).

- Money's purpose in my life is to support a calm, fulfilling, and enjoyable lifestyle.

- Money's purpose in my life is to allow me to share experiences with my family and raise responsible, independent children.

- Money's purpose in my life is to live life fully and contribute generously.

- Money's purpose in my life is to provide security and stability to my family. It should never be valued over relationships or my values. Excess should be freely and joyfully shared with others in need.

- Money's purpose in our lives is to allow us to spend quality, connected time together as a family, supporting a lifestyle that satisfies our needs with opportunities to give, travel, and save.

- Money's purpose in my life is to enable me to live life to the fullest.

Notably, these examples don’t involve simple equations. For some clients, a concise statement will work well. For others, a longer statement will work better. The right answer is what speaks to the client.

Using A Financial Purpose Statement To Live More Intentionally

A client's Financial Purpose Statement becomes the lens through which they view their financial life. Advisors can use them to help clients live their lives more intentionally by encouraging them to focus their decisions towards the role money needs to play for them.

I print and laminate a client's Financial Purpose Statement for them. I give them a larger (3.5” x 5.5”) version as well as two smaller wallet-sized versions. Some clients like to keep them visible, such as around their desk or on a tackboard. Others will keep a copy in their purse or their wallet, so they have it with them at all times. One client printed their Financial Purpose Statement on a large sheet of paper and framed it.

But that's just how I use Financial Purpose Statements with my clients. Advisors can figure out what works best to serve their own clients. Some examples might be to put Financial Purpose Statements at the top of clients’ Investment Policy Statements, or to include it on all of their investment reports, or at the top of their One-Page Financial Plan.

Alternatively, advisors might choose to review it at the beginning of each meeting, restating the client’s Financial Purpose Statement at the top of every review meeting agenda. When clients face a tough decision, they can be guided through their decision with reminders of their financial purpose.

Clients can think of their Financial Purpose Statement as the foundation of the rest of their financial lives. All aspects of their financial lives, including the work that they do, their goals, how they manage their cash flow, when and how they want to retire, and even lifestyle decisions rest on the foundation of what their money needs to do for them, both currently and in the future.

Below are some examples of how clients have benefited from the use of a Financial Purpose Statement.

Example for an Overspender: Jackie is an overspender. She grew up in poverty and only got out of her situation after effectively running away. She eventually made her way into college and became a successful professional earning a six-figure salary. Now that she finds herself with an upper-middle-class lifestyle, it's easy for her to justify buying things that she could never have when she was growing up. Unfortunately, Jackie knows she should be spending less and saving more, but information alone hasn't been enough to help. She doesn't save enough of her paycheck and sometimes dips into her portfolio to help cover her spending.

Jackie's advisor helped her craft a Financial Purpose Statement that reads: Money's purpose in my life is to provide security and peace of mind for my family and me. Jackie's advisor helped her understand how to use her financial purpose to increase the space between impulse and purchase by simply asking herself if the purchase she's about to make is in alignment with her financial purpose. It is essentially a way to intentionally introduce the pain of paying.

Now, whenever Jackie feels like making a purchase, she remembers to look at her Financial Purpose Statement. That's all she has to do. If, for example, Jackie feels like buying a hot tub after visiting a friend who has a hot tub, she simply asks herself if buying a hot tub will provide security and peace of mind for her family. Often, the answer is no. Sometimes the answer will be yes. Either way, by using her Financial Purpose Statement, Jackie can make decisions intentionally and not impulsively.

Example for an Underspender: Jason is a saver. He's been saving his whole life and is proud of the nest egg he's been able to accumulate. He grew up watching his father make some bad financial decisions and end up bankrupt. He vowed that that would never happen to him, so he decided money was to be saved and not spent.

Now that he's getting to the age where he wants to stop working, it's hard for him to imagine not being able to save, and even harder to imagine having to rely on his savings for his living expenses. He and his wife fight regularly because he believes she spends too much, and she believes he’s too cheap. Although they have an eight-figure net worth, Jason still stresses out over relatively small purchases that feel like too much to him, like when the restaurant tab for a family of five is over $100.

When Jason and his wife visited their financial advisor, their advisor guided them through some priming exercises, including the Tape Measure exercise. This exercise helped the two of them realize that life is short. Importantly, Jason realized that he didn’t have many more active years left and that leaving millions to his children wasn’t his main goal.

Their advisor helped them craft a combined Financial Purpose Statement that reads as follows:

Money's purpose in our lives is to share our fortune with family and community, and to enable happy, meaningful times for the two of us.

The advisor helped Jason and his wife understand how they could think about their financial life through the lens of their financial purpose. It was helpful for them to be reminded that money is not a goal, but rather a tool they can use to enjoy the fruits of Jason's labor.

Now, Jason and his wife can enjoy vacations, renovations to their house, and even date nights out without fighting about spending too much.

Example for a Social Comparer: Phil is a real estate agent and has trouble avoiding social comparison. He jokes that he not only wants to keep up with the Joneses, but that he wants to be the Joneses. When he sees other people with a newer phone, fancy gadget, or other luxuries that he doesn't have, he feels an immense feeling of deprivation. He feels that he is missing out. In many ways, it’s not his fault; he works in an industry that focuses heavily on status. He feels that being a real estate agent makes him feel compelled to impress potential clients and even other agents.

After guiding Phil through some life-in-perspective exercises, his advisor helped Phil craft a Financial Purpose Statement that reads, “Money's purpose in my life is to help me connect and create.” The exercises leading up to the creation of his Financial Purpose Statement really helped Phil ground his identity to his personal values.

Being guided through these exercises revealed an epiphany that helped Phil realize he’d been using his money, time, and energy in ways that didn’t align with what was important to him. Phil’s advisor helped him realize that he feels happiest when he’s connecting with other people and engaging in creative pursuits.

Over time, Phil has learned to compare himself to prior versions of himself rather than to others. It has taken practice, but when he feels a sense of deprivation, Phil checks in with his Financial Purpose Statement and simply lets that feeling pass.

When teaching clients how to use a Financial Purpose Statement, it's important to highlight the fact that this is not meant to be a deprivation tool; instead, it should be thought of as an intentionality tool. If clients can find a loophole and justify their purchases or their decisions, that's actually okay. Because having intentional thoughts about whether to make the decision to find a loophole in the first place, in fact, serves to help them put space between the initial stimulus that triggers their desire to make a decision and their final response, ending out with a more thoughtfully considered outcome that can be recognized in the context of their Financial Purpose Statement.

Helping clients think through and craft a Financial Purpose Statement encourages them to become more mindful of their financial decisions and to become less susceptible to social comparison. By thinking about the kind of lives they want to live, they can use their money as a tool to design – and live! – that life, so that they can enjoy happier lives and, in the end, look back with fewer regrets.