Executive Summary

As almost all financial advisors have experienced, instilling behavior change in clients can be a tough task. Though we can easily see ways in which clients could improve their behavior for the better (which are often known by clients as well), the reality is that merely telling clients about how they can improve their behavior is rarely enough to actually get them to do so. While there are many reasons why this could be the case, one common barrier to behavior change is that if the client isn't self-confident in his/her own ability to successfully make the change in the first place – lacking the "self-efficacy" to be successful – then the change simply doesn't happen.

In this guest post, Dr. Derek Tharp – a Kitces.com Researcher, and a recent Ph.D. graduate from the financial planning program at Kansas State University – examines the concept of financial self-efficacy (i.e., one's confidence in their ability to complete a financial task), and looks at how research might suggest that financial advisors can help their clients build greater levels of confidence in their own ability to actually engage in (and therefore adopt) better financial behaviors.

Though it is not a term that is as popular outside of academic circles, "self-efficacy" is a broader concept which refers to one's confidence in their ability to engage in a particular behavior. Growing out of research related to positive psychology (the study of what makes people flourish), self-efficacy has been found to be an important concept related to promoting good behavior in many areas of life. Though research specifically within a financial planning context is still limited, some early findings suggest that promoting the practice tenets of positive psychology captured within the PERMA framework – which posits that Positive emotions, deep Engagement in activities, worthwhile Relationships, finding Meaning in one's life, and Achieving a sense of accomplishment – may be ways in which financial advisors can help clients improve their financial self-efficacy.

Additional research on self-efficacy more generally suggests that performance accomplishments (e.g., helping our clients develop skills that they need to be confident in taking action), vicarious experience (e.g., serving as a good financial role model for our clients), verbal persuasion (e.g., providing encouragement when our clients need some financial coaching), and emotional arousal (e.g., encouraging/discouraging financial decision making when clients are in ideal/non-ideal levels of emotional activation) may all be effective ways that financial planners can help their clients build financial self-efficacy. As a result, financial planners who wish to help their clients implement better financial behaviors should not ignore the potential power of promoting financial self-efficacy. When it comes to helping clients make good decisions, helping clients believe they can accomplish the financial behavior in the first place is crucial!

What is Financial Self-Efficacy?

Financial self-efficacy refers to one’s beliefs in his or her own abilities to accomplish a financial goal or task.

While self-efficacy may not be a term commonly heard outside of academic discussions, it is a concept with many applications for financial planners. Initially developed by psychologist Albert Bandura, Professor Emeritus at Stanford University, self-efficacy is actually a broader psychological concept which can apply to any area of one’s life.

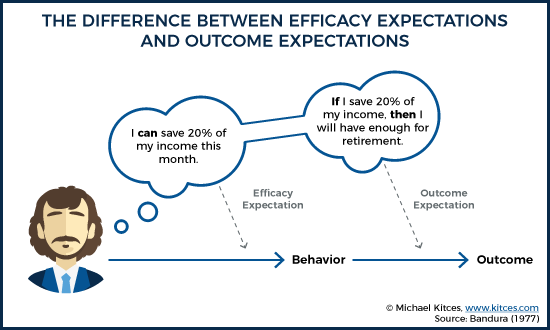

Self-efficacy relates specifically to one’s expectations of their ability to engage in a particular behavior, which is distinct from one’s expectations about the outcome of that behavior.

In Bandura’s seminal article on self-efficacy in Psychological Review, he says (p. 193):

An outcome expectancy is defined as a person’s estimate that a given behavior will lead to certain outcomes. An efficacy expectation is the conviction that one can successfully execute the behavior required to produce the outcomes. Outcome and efficacy expectations are differentiated, because individuals can believe that a particular course of action will produce certain outcomes, but if they entertain serious doubts about whether they can perform the necessary activities such information does not influence their behavior.

In other words, we can fully understand that saving and investing is essential to building a healthy retirement income, but if we don’t believe that we can afford to spend less and save more in the first place, knowledge about the benefits of saving and investing may not influence our actual behavior.

Similarly, it’s important to emphasize that self-efficacy does not refer to one’s skills or knowledge. An individual could have objectively high levels of financial skills and knowledge, yet still lack the self-confidence and financial self-efficacy needed to engage in behavior that capitalizes on this knowledge.

Notably, the concept of self-efficacy is relevant to the distinction between financial literacy and financial knowledge drawn by Texas Tech University professor Sandra Huston in her 2010 Journal of Consumer Affairs article, who suggests (p. 307):

Financial knowledge is an integral dimension of, but not equivalent to, financial literacy. Financial literacy has an additional application dimension which implies that an individual must have the ability and confidence to use his/her financial knowledge to make financial decisions.

In other words, financial education may make someone more financially knowledgeable, but they’re not “financially literate” until they have the ability and the confidence to actually put that knowledge to use for themselves. And financial self-efficacy is an important concept to tie into financial literacy, because self-efficacy is a key component of actually changing one’s financial behaviors for the better!

Research on Financial Self-Efficacy

While the research on financial self-efficacy in particular (as opposed to self-efficacy in general) is limited, a number of scholars have been conducting research which can provide some guidance regarding how self-efficacy may apply in a financial context.

For instance, researchers have examined research questions such as how financial self-efficacy influences the financial behavior of women, is best measured, influences credit behavior, predicts financial behavior, influences the use of financial services, influences college major choice, and how financial attitudes mediate the relationship between financial self-efficacy and financial behavior.

Notably, much of the existing research relates to how financial self-efficacy influences behavior. As we would expect, higher levels of financial self-efficacy generally lead to greater likelihood of participating in positive financial behaviors. Yet while these findings do lay an important foundation, they aren’t particularly insightful for most financial planners, given that as financial planners we aren’t interested in merely knowing that financial self-efficacy can improve financial behavior… but rather, would like to know how we can help our clients develop a greater ability to engage in positive financial behaviors.

Fortunately, one early strand of research from Sarah Asebedo, an assistant professor of personal financial planning at Texas Tech University, has begun to examine the question of how financial self-efficacy beliefs might be fostered, particularly as they relate to saving behavior among those approaching retirement. Specifically, Asebedo’s dissertation, which was a 2017 recipient of the Robert O. Herrmann Outstanding Dissertation Award from the American Council on Consumer Interests, examines financial self-efficacy beliefs and saving behavior of older pre-retirees. And beyond just looking at the relationship between beliefs and behavior, Asebedo also examines psychological factors which may promote financial self-efficacy beliefs among older pre-retirees.

Drawing on insights from positive psychology (a domain of psychology dedicated to studying what makes people flourish, rather than just focusing on mental illness), Asebedo utilizes the PERMA framework, originally outlined in Martin Seligman’s book Flourish, which posits that Positive emotion, Engagement, Relationships, Meaning, and Achievement promote well-being.

Drawing on insights from positive psychology (a domain of psychology dedicated to studying what makes people flourish, rather than just focusing on mental illness), Asebedo utilizes the PERMA framework, originally outlined in Martin Seligman’s book Flourish, which posits that Positive emotion, Engagement, Relationships, Meaning, and Achievement promote well-being.

Ultimately, Asebedo finds that there is a positive relationship between financial self-efficacy beliefs and saving behavior, and that PERMA factors were associated with higher levels of financial self-efficacy. Which means that financial advisors who do want to promote higher levels of self-efficacy among clients may be able to do so by encouraging them to adopt practices consistent with the PERMA framework—such as participating in activities that provide feelings of positive emotion, engaging in hobbies or work that are so engrossing that we experience a state of “flow”, fostering strong relationships with friends and family, participating in activities so deeply aligned with our goals and values that we build a sense of meaning in our life, and pushing ourselves in pursuits that are meaningful to us so that we can develop a true sense of accomplishment.

How We Build Self-Efficacy

In addition to financial self-efficacy research specifically, we can also turn to self-efficacy research more generally to gain some potential insight on ways in which financial advisors can promote financial self-efficacy among their clients.

In Bandura’s article, he argued that social learning is an important way in which we build efficacy expectations. In particular, Bandura’s theory indicates that we acquire our expectations through learning based on four primary sources: performance accomplishments, vicarious experience, verbal accomplishments, and emotional arousal.

Performance Accomplishments

Performance accomplishments refer to ways in which we learn from our successes and failures in attempting a given task. Based on feedback from our peers and self-evaluation, we develop more or less confidence in our ability to execute a particular behavior successfully. Generally speaking, the more success we attain, the higher our perceived mastery and the greater our confidence that we can be successful.

Unfortunately, unlike a coach who can help a player practice a certain element of a sport so that it can be applied in a game setting, it is much harder to help clients “practice” financial behavior. Many of the scenarios that can get an individual into financial trouble—particularly behavior with a highly emotional element, such as panic selling or making compulsive purchases—is inherently hard to practice without experiencing the real emotions in the moment. It’s one thing to practice not panic selling by walking a client through a simulated market downturn, but it is inherently different when a retiree is watching their actual nest egg decline.

That said, there are some areas financial planners could likely help their clients practice good financial behavior. In many cases, the barrier to a particular financial behavior may be driven by technology or some other factor that is not inherently financial. For instance, suppose a client struggles to put together a monthly budget because the process requires going online to retrieve some key information and they are uncomfortable with technology. This individual may exhibit low budgeting self-efficacy, yet that low self-efficacy may be entirely unrelated to budgeting per se.

Aside from seeing if there’s a way that the client could get the same information without going online, a planner could devote actual client meeting time to coaching the client through the process of retrieving the needed information, or even helping them set up and configure Personal Financial Management tools (e.g., a Mint.com account, or an industry PFM solution like eMoney Advisor). As the client builds confidence to engage in the behavior needed to carry out their budgeting task, their budgeting self-efficacy will rise.

Similarly, clients who lack confidence in their ability to navigate and implement changes in a 401(k) or other online investment portal may miss out on opportunities to boost their savings rates as their pay increases, not because they are unwilling to boost their savings or unaware that it will help them reach their financial goals, but simply because they lack the confidence to successfully utilize the tool in the first place. Since these fleeting moments of change can be important opportunities to help clients take action before becoming accustomed to their new income, financial advisors may want to invest time in ensuring that clients have the confidence in their abilities to make such changes when the time comes!

Financial planners may also want to be cognizant of situations in which actual therapeutic intervention may benefit their clients. For instance, individuals with agreeable personalities have been found to earn less, likely due to tendencies to avoid behavior that could increase their earnings (such as negotiating harder for a pay raise). Assertiveness training is one form of therapy which can help individuals build skills needed to be confident in negotiation. Of course, any psychological intervention should only be conducted by a qualified professional, but financial planners can always refer clients to a qualified financial therapist or merely encourage clients to be assertive and remind them of the financial significance of behavior such as negotiation.

Vicarious Experience

Vicarious experience refers to the ways in which we model our behaviors after those around us. For instance, we may look to a supervisor or someone who has been successful in a position we aspire to attain and pick up behavior from them. Though this type of learning doesn’t speak to our own abilities per se, it can still reduce our uncertainty regarding how we should act, and seeing others successfully complete a task can still boost our confidence in our ability to do the same.

Most obviously, financial planners can model good financial behaviors for clients. In practice, however, modeling good financial behavior for clients is difficult for the obvious reason that clients generally won’t be around us to witness our behavior in the moment. In contrast to how a junior advisor can credibly watch how steady and consistent prospecting efforts manifests in success for a senior advisor in the long run, clients will, at best, generally need to rely on second-hand accounts of our behavior we may wish to model to them. In fact, arguably it is our misinterpretations of vicarious experience—such as seeing a neighbor that drives a fancy car and believing that we need to do the same—that unwittingly leads to a lot of adverse outcomes when the “social proof” we often rely on is leading us to negative behavior rather than positive behavior!

Nonetheless, that doesn’t mean we can’t be good financial role models for our clients. Particularly given the communication opportunities available today through blogging, vlogging, or even just periodic messaging through social media, financial advisors have more opportunity than ever to help clients build financial self-efficacy through vicarious experience. Whether such communication is through timely articles on “Why we’re buying and not selling today” during a down market, or more personal communication such as sharing a quick Instagram video with a tip on avoiding impulse purchases while an advisor is out doing their own shopping, the opportunities to be an ongoing role model to our clients (outside of a few meetings per year) have never been greater!

Verbal Persuasion

Verbal persuasion refers to the ways in which humans can motivate and influence one another. For instance, a coach may instill belief in an athlete that he or she can attain success under conditions in which the athlete does not have prior experience or has failed in the past. Similarly, the power of a trusted advisor who simply says, “You can do it – I believe in you,” should not be underestimated.

The potential to influence financial self-efficacy through verbal persuasion has some clear implications for financial coaches. However, even financial advisors who may not see themselves as a “financial coach” can still leverage verbal persuasion to help clients build financial skills.

Some thoughtful encouragement can help increase a client’s confidence to take action in a wide range of settings—from setting up an estate plan and purchasing insurance, to getting one’s financial house in order and having tough conversations about money.

For instance, in order to help a client build the confidence they need to engage in a tough (though important!) conversation at work like asking for a raise, an advisor may actually want to roleplay with the client and coach them through the conversation. Similar to how an athletic coach can help an athlete practice to build the confidence needed to perform when it matters the most, financial advisors can use an advisor’s office as a safe environment to learn what things to say and how to say them when the client can’t have a coach by their side. And similar to how social media can allow advisors to increasingly serve as good role models for clients, mobile communication technology makes it easier than ever for advisors to be in communication with their clients when it matters most—perhaps even checking in for a quick coaching call right before a client’s big moment.

Emotional Arousal

Emotional arousal refers to the ways in which our emotions can influence our confidence in our ability to be successful. Emotional arousal can either increase or decrease one’s self-efficacy. For instance, fearful thoughts may reduce one’s self-efficacy beyond what the conditions would rationally warrant (e.g., the fear of being told ‘No’ which keeps financial advisors from prospecting), whereas a nervous energy can be channeled into focus.

Of the various ways in which Bandura suggests self-efficacy is built, emotional arousal may be one of the most difficult for financial planners to intentionally leverage as a tool in the planning process, though fortunately financial therapy researchers have begun to examine the role of emotional arousal in the context of a financial planning meeting.

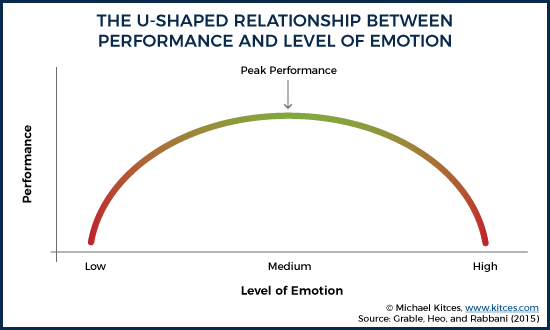

For instance, Grable, Heo, and Rabbani (2015) examined the ways in which financial anxiety and physiological arousal influence financial planning intention (i.e., one’s intent to hire a financial planner in the future). In their review of existing research, the authors note that performance often exhibits an inverted U-shape relationship with physiological activation. The authors note that in athletic competition, it is often a moderate level of emotional stimulation which leads to the best performance.

Grable, Heo, and Rabbani measured physiological arousal through peripheral skin temperature as individuals participated in an interview in a financial counseling clinic. In describing their methods, the researchers say:

At the end of the interview, participants were asked, “On occasion, the clinic offers financial planning services to the community. If an opportunity arose to meet with a financial planner, on a scale of 1 to 10, with 10 being absolutely certain and 1 being very unlikely, how likely is it that you would be willing to set up an appointment to meet with a financial planner?”

The researchers ultimately found that physiological arousal did influence one’s self-reported willingness to participate in a follow-up meeting with a financial planner. However, the researchers note that the relationships were not as straightforward as expected, concluding that “…short-term arousal itself may, in fact, help focus attention and promote action. It is not, however, arousal alone that matters. It is the interrelationship with financial anxiety—or longer-term financial stress—that appears to shape planning intention.”

While some more nuance is certainly needed in order to understand how financial planners can best leverage emotional arousal in a client meeting, it is almost certainly true that emotional arousal can either promote or inhibit financial self-efficacy. This may be particularly true in the context of highly emotional financial decisions, such as those related to divorce, life insurance, and estate planning.

As a result, financial advisors may want to be cognizant of a client’s emotional level when making important financial decisions. For instance, advisors may not want to present clients with a challenge to save an additional 5% of their income next year when the client is completely emotionally deactivated (perhaps due to a highly technical investment review that was 45 minutes longer than they wanted). Similarly, advisors may wish to refrain from asking clients to make decisions when they are overly emotional. If a client just broke down in tears talking through financial goals or other considerations, their level of emotional activation may be too high for optimal decision making. Instead, if a client is adequately primed emotionally for the importance of a decision—perhaps feeling the emotional weight that underlies the seriousness of decisions such as purchasing life insurance without being overwhelmed—then the client may be in a good emotional state to achieve a higher level of financial self-efficacy, as the extra emotional weight may instill the confidence needed to push past a barrier that has been previously hard to overcome.

Though it’s not a term many of us are likely familiar with, financial self-efficacy is an important concept for financial planners to understand and help promote in clients. Our clients’ confidence in their ability to carry out a financial behavior is ultimately a key driver of successfully implementing a financial plan. Whether it is through promoting the positive psychology concepts within Seligman’s PERMA framework (e.g., the importance of engaging in activities that promote meaningful accomplishments that provide us with positive emotion); looking for opportunities to leverage performance accomplishments (e.g., developing skills with our clients that they need to be confident in taking action), vicarious experience (e.g., serving as a good financial role model for our clients), verbal persuasion (e.g., providing encouragement when our clients need some financial coaching), or emotional arousal (e.g., encouraging/discouraging financial decision making when clients are in ideal/non-ideal levels of emotional activation) in helping clients build financial self-efficacy; or even some yet to be identified methods that financial planners can utilize with their clients, financial self-efficacy is an important tool for promoting good financial behavior.

So what do you think? Is financial self-efficacy an important concept for helping clients engage in better financial behavior? What are your favorite strategies for helping clients boost their financial self-efficacy? Please share your thoughts in the comments below!

This article is of particular interest to me. As a former mental health counselor, I believe in the use of cognitive behavioral therapy techniques when addressing financial obstacles that clients are facing. I am mindful not to act as my clients’ therapist (that is not my role), but some of the techniques are very applicable to helping clients change their financial behavior and decision-making. I cringe when I see advisors dole out advice in the “I’m the expert-do as I say” manner. Not surprisingly, most clients have a hard time following such advice. And a word to the wise: if you are not skilled in this area, don’t practice it on your clients. Get some training first!

Excellent article, Derek. This is an area where an advisor might want to work in tandem with a financial coach who could work more intensively with the client, or refer the client to a financial therapist. Motivational Interviewing is also a very effective technique for increasing the client’s intrinsic motivation to change.

Mind over money and having a positive attitude will definitely go far in reaching your dreams. It’s incredible how looking back and where one started has got you to where you are now. A lot of the times what you thought would never happen, happens and then happens even bigger than you originally thought. So why not dream big! 🙂