Executive Summary

Tax-deferred accounts have long been a boon to savers, allowing them to earn additional growth on top of the growth without Uncle Sam taking a share. But tax-deferred doesn’t mean tax-free, and sooner or later, Uncle Sam will eventually take his share, since each and every retirement account is subject to Required Minimum Distribution (RMD) rules at some point (even Roth accounts, after the death of the original owner!).

Unfortunately, though, the RMD rules can be maddeningly complicated, making it easy for taxpayers to make a mistake by taking a smaller-than-required distribution, taking a distribution from the wrong account (or even the wrong type of account), or (worse yet) missing a distribution altogether. In fact, mistakes in satisfying RMD obligations are so widespread among retirees that in just 2006 and 2007, over a quarter-million individuals failed to take an RMD from their IRAs alone... not to mention all the other types of tax-preferred accounts out there. And given that RMD rules haven’t changed, it’s not a stretch to assume that the number of missed distributions hasn’t gotten any better… especially given that Baby Boomers have since been retiring in droves and reaching the age 70 ½ threshold when RMDs begin.

The problem, of course, is that, not only does a taxpayer still have to catch up on any of their distributions that were missed (which could end out having adverse tax consequences if a large enough amount has to be taken), but the IRS will impose an additional penalty of a whopping 50% of the amount that was supposed to have been distributed in the first place… even if the mistake was purely unintentional!

The good news, though, is that the IRS isn’t entirely without compassion and understanding (truly!), and has the option to decide to waive that punitive penalty for failing to take an RMD. However, it’s important to note that the onus is on the taxpayer to reach out to the IRS, explain that their mistake was the result of a “reasonable error,” and show how they are taking “reasonable steps” to remedy the shortfall.

Unfortunately, though, the bad news is that, although there is a way to waive the 50% penalty, the means for doing so can be just as confounding as the RMD rules themselves… at least if the taxpayer hopes to have their penalty abated!

The first step towards requesting a waiver for a failed RMD is to take the missed distribution(s) as soon as possible, preferably separately and without any additional taxes withheld (so that the amount deposited into a receiving account exactly matches the shortfall). From there, the taxpayer must (correctly) file the appropriate Form 5329 for each of the years that a distribution mistake was made. The caveat is that there is one line in particular - line 54 - which can easily throw a wrench in the works, as the proper way to request the penalty waiver is to not fill out the line the way it is explained on Form 5329 itself, and instead to mark a request for waiver next to that line instead. And, in addition to that, the taxpayer must also attach a letter explaining the reasonableness of both their error and their corrective measure to the IRS.

In the end, the key point is that, while RMD mistakes are common among owners (and beneficiaries) of tax-preferenced retirement accounts, it’s actually quite likely that the IRS will waive the 50% penalty… but only if the appropriate steps are taken in a timely manner to rectify the error. Because while it may be tempting to “roll the dice” and hope that the IRS doesn’t figure out that a mistake’s been made (and then feign ignorance if/when they discover the error), the reality is that it’s far less likely that the IRS will be as understanding had the taxpayer self-reported the mistake in the first place! Especially since the failure to file a Form 5329 to report (and request a waiver of) the penalty means the statute of limitations itself for the 50% penalty never begins to toll in the first place!

Required minimum distributions (RMDs) are a hallmark of retirement accounts. Even Roth IRAs, which have no RMDs during the Roth IRA owner’s lifetime, become subject to such requirements once a non-spouse beneficiary inherits the account. Thus, it’s fair to say that if not spent sooner, each and every retirement account is subject to RMD rules at some point. Because eventually, Uncle Sam wants a crack at those tax-preferenced accounts (or at least, the taxable growth that will occur outside of them in the future).

Unfortunately, though, the RMD rules are deceptively complicated, and it's easy for a mistake to be made. This can sometimes lead to a smaller-than-actually-required “RMD” being calculated. Other times, RMDs are calculated correctly, but taken from the wrong account type. And sometimes, retirement account owners and/or beneficiaries simply ignore or forget RMDs altogether!

Indeed, some six years before even the first of the Boomers reached 70 ½ (significantly increasing the number of Americans required to take such distributions), the IRS discovered it was already dealing with massive noncompliance. A March 2010 report by the Treasury Inspector General for Tax Administration indicated that during the 2006 and 2007 tax years, an estimated 255,498 individuals had failed to take an RMD! And notably, that report only looked at IRAs, which begs the question, “How many more people were there who missed RMDs, but from 401(k)s, 403(b)s, 457 plans, Thrift Savings Plans, etc.?” as well!?

Given that not much has changed over the last decade or so in terms of simplifying RMDs, one has to imagine that as the number of individuals reaching 70 ½ (or older) has begun to rapidly expand with the shift of Baby Boomers past the RMD age threshold, the number of retirement account owners failing to correctly take one or more RMDs has ballooned in a similar fashion.

The Penalty For A Shortfall In A Required Minimum Distribution

They’re called “required minimum distributions,” and not “We’d-really-like-it-if-you-would-take-these distributions” for a reason… they have to be taken. And just as children are often punished when they fail to do something which has been required, so too are owners of retirement accounts who fail to properly take an RMD. More specifically, IRC Section 4974(a) states:

“If the amount distributed during the taxable year of the payee under any qualified retirement plan or any eligible deferred compensation plan (as defined in section 457(b)) is less than the minimum required distribution for such taxable year, there is hereby imposed a tax equal to 50 percent of the amount by which such minimum required distribution exceeds the actual amount distributed during the taxable year. The tax imposed by this section shall be paid by the payee.” (emphasis added)

Thus, any shortfall in a required minimum distribution (an amount that was supposed to be distributed, but was not) is subject to a (massive) 50% penalty. This penalty is more formally known by the IRS as the “Additional Tax on Excess Accumulations."

Example #1: Ashley is 75 years old and is the owner of a single Traditional IRA. For 2018, the required minimum distribution for his IRA account was correctly calculated at $10,000, but Ashley failed to take that distribution before the end of the year. He is, therefore, subject to penalty for the error of $5,000 = $10,000 x 50%.

It’s important to recognize as well that the penalty for a failure to take the RMD obligation applies regardless of the reason that the failure occurs… even if due to a pure accident. (Though as discussed below, in some such situations, the IRS may decide to grant a waiver to the penalty.)

Example #2: Belle is 85 years old and is the owner of a single Traditional IRA. For 2018, her required minimum distribution was calculated at $60,000. Unfortunately, Belle’s hearing is not as good as it once was, and when she called her financial institution to inquire about her RMD amount, she thought they said “$16,000”.

In November of 2018, to satisfy what she believed to be her RMD, Belle took a distribution of $16,000 (from her IRA). This was the only money she took from her IRA during 2018. As such, Belle is subject to a penalty of $22,000 = ($60,000 - $16,000) x 50%.

Requesting A Waiver (Abatement) Of The 50% Penalty For An RMD Shortfall

While the 50% penalty for a missed RMD seems (and is) rather harsh, the good news for (the many) people who fail to satisfy one or more RMDs during a year is that, unlike other penalties that can apply to retirement account owners (i.e., the 6% penalty for excess contributions, the 10% penalty for early distributions), IRC Section 4974(d) allows that IRS to abate (waive) the 50% penalty.

Paragraphs (1) and (2) of that IRC Section 4974(d) subsection go on to provide that in order for the IRS to waive the penalty, an individual must show that their RMD shortfall was due to “reasonable error”, and that they are taking “reasonable steps” to remedy the shortfall.

That’s all well and good, but how do you actually do that, practically speaking? What sort of steps can an individual who’s had a shortfall in an RMD amount do to show they’ve taken “reasonable steps” to correct the error? And how does one actually convey to the IRS the (reasonable) reason the shortfall occurred, to begin with?

Show Reasonable Steps Are Being Taken To Remedy A Shortfall By “Making Up” (Distributing) Any Missed RMDs As Soon As Practicable

When a missed RMD is discovered, the first step in seeking an abatement of the 50% penalty is to take corrective action as soon as possible. In other words, “stop the bleeding.” This is best accomplished by determining the amount of each RMD that was missed, and then taking distributions of those amounts as soon as possible. Even if it’s already well past the deadline for the original tax year the RMD was due.

While there is no requirement to do so, from a practical perspective, if a shortfall in more than one year, and/or more than one account, has been identified, it is best to have each year’s/account’s shortfall remedied via a separate distribution (to most easily demonstrate to the IRS that the proper corrective actions, for each/every amount in question, was taken). Furthermore, taxpayers should consider having no taxes withheld from the distributions, so that the checks they receive (or the electronic deposits made to their accounts) precisely match the amount(s) reported to the IRS as shortfalls (more on this part of the “equation” in a bit).

Remember, the actual decision of whether or not to abate an individual’s 50% penalty will be made by a human, not a machine (yet). So, in short, it’s a good idea to make things as easy as possible so you can earn whatever “brownie points” might be available with the IRS agent in charge of reviewing the abatement request. Matching up check/deposit amounts to requests for relief helps them to do that.

(Note: Theoretically, there shouldn’t be any such thing as “brownie points,” and an IRS agent’s decision should be based solely on an analysis of the corrective actions and the reason provided for the error(s) presented by a taxpayer. But theory and reality don’t always perfectly align. IRS agents are humans (yes, complete with heart, and all), and it is simple human nature that when others are helpful to you – making your work-life a bit easier, for instance – you are helpful to them in return.)

Also worth noting is that when an individual takes a distribution from an IRA or other retirement account to correct a previous RMD error, there is no automatic notification made to the IRS explaining the nature of the corrective distribution. Instead, the 1099-R provided to the taxpayer at the beginning of the next year that includes the make-up distribution will simply report the distribution as a “Normal Distribution,” using Code 7 in Box 7 of the form. Thus, such a corrective distribution (or distributions) will look exactly like a “regular” distribution to the IRS… which is why this is just the beginning of the correction process.

File Form 5329 (Additional Taxes on Qualified Plans [Including IRAs] and Other Tax-Favored Accounts) For Each Year An RMD Was Missed

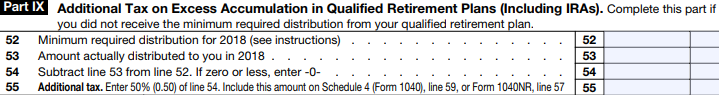

Once an individual has taken remedial action with respect to an RMD shortfall (i.e., actually taken out the amounts that weren’t withdrawn in the first place), they should make sure that they report their error, and formally ask for “forgiveness” from the IRS. This is done by filing Form 5329, Additional Taxes on Qualified Plans (Including IRAs) and Other Tax-Favored Accounts, and properly completing Part IX, Additional Tax on Excess Accumulation in Qualified Retirement Plans (Including IRAs).

(Note: Part IX of the 2018 Form 5329 – the most recent year for which a Form 5329 has been published by the IRS – is used to report the Additional Tax on Excess Accumulation in Qualified Retirement Plans (Including IRAs) for such matters occurring in 2018. However, in previous versions of the form, the Additional Tax on Excess Accumulation in Qualified Retirement Plans (Including IRAs) was reported in a different/earlier section.)

If RMD corrections are limited to a single year, then a single Form 5329 from the year in which the RMD(s) was (were) missed should be filed. Thus, for instance, if in 2019 an individual discovers that they forgot to take an RMD in 2017, after “making up” the distribution, they should file a 2017 Form 5329… even though the form (the 2017 Form 5329) itself, isn’t being filed until 2019.

The filing of a single Form 5329 is sufficient as long as all RMD shortfalls are attributable to the same individual’s retirement accounts, and as long as the shortfalls occurred for the same (original) tax year.

In other situations, however, the filing of multiple Form 5329s is generally necessary. For instance, if a married couple both miss an RMD during the same year from their respective IRAs, they must each file their own Form 5329 for that year to request relief. Form 5329 is applicable only to an individual taxpayer… even if that taxpayer files a joint return.

In addition, if a taxpayer misses RMDs during multiple years, a separate Form 5329 should be filed for each year that an RMD shortfall occurred, using the specific Form 5329 for that year.

Example #3: Rhett and Scarlett are married taxpayers who file a joint return. Rhett turned 70 ½ in May of 2015, and Scarlett turned 70 ½ in June of 2017. Both have owned IRAs since the 1980s.

In May of 2019, the couple decided to meet with a financial advisor, who noticed that no distributions were being taken from either of their IRAs. And upon closer investigation, it was discovered that neither Rhett, nor Scarlett, had ever taken even a single dollar of their required minimum distributions.

In order to avoid being subject to the 50% penalty on the missed RMDs, after “making up” the missed distributions, Rhett and Scarlett must file the appropriate Form 5329s. In this case, it means Rhett would file a 2015 Form 5329, a 2016 Form 5329, a 2017 Form 5329, and a 2018 Form 5329 to report the specific shortfall in required distributions that occurred in those years. Similarly, a separate 2017 Form 5329, and a 2018 Form 5329, should be filed to report Scarlett’s missed RMDs.

“Correctly” Complete Form 5329 To Avoid Common Traps

Requesting relief from the 50% shortfall-in-RMD penalty is deceptively complicated. Indeed if one were to look at Form 5329, by itself, without first thoroughly reading through the Form 5329 Instructions, it’s likely that the form would be completed incorrectly, significantly reducing the chances of securing the desired penalty abatement.

To avoid making such mistakes, below are the line-by-line steps – in “English” – that a person should take to correctly complete a 2018 Form 5329, in order to request a waiver of the 50% RMD penalty. (Note: The same general rules apply to previous version of the form, but the lines on which the information is reported may be different).

Following The Instructions For Part IX, 2018 Form, Additional Tax on Excess Accumulation in Qualified Retirement Plans (Including IRAs)

Line 52: This one is pretty straightforward. Simply indicate the correct amount of cumulative RMDs that the retirement account owner was supposed to take. Only include RMDs from the account(s) for which there was an RMD shortfall.

Line 53: Here, a taxpayer should indicate whether they took any amounts of the RMD from the account(s) for which there was an RMD shortfall. If no distributions were made from that/those accounts during the year in question, Line 53 should be “$0”.

Line 54: Here’s the place where the majority of mistakes occur. The text of Line 54 on Form 5329 is seemingly innocuous and reads (in part), “Subtract line 53 from line 52. If zero or less, enter -0-”. It looks like simple math, but it’s anything but.

Simply following the guidelines on the actual form, one would logically complete some basic subtraction, put the answer on Line 54, and move on to complete the form… but’s that’s not how the form is supposed to be completed when requesting an abatement of the 50% penalty! Worse yet, completing it in that manner will likely spoil any attempt at securing a waiver.

Rather, when a taxpayer is seeking relief from the 50% penalty, they should ignore the instructions provided on Line 54 of Form 5329. I repeat…

WHEN A TAXPAYER IS SEEKING RELIEF FROM THE 50% PENALTY, THEY SHOULD IGNORE THE INSTRUCTIONS PROVIDED ON LINE 54 OF FORM 5329!

Instead, a deep dive into the instructions for Form 5329 yields that the proper way to complete Line 54 when requesting a waiver of the 50% penalty is to write “$0”! Then, to the left of actual Line 54, on the dotted line, a taxpayer should write “RC” (short for reasonable cause), followed by the amount of the RMD shortfall on which they would like the 50% penalty waived.

In essence, the “standard” instructions for Line 54 actually help to calculate the amount on which a penalty will be owed. If the desire is to have the penalty abated, the proper process is to report no shortfall in the RMD, and make the case that it was timely corrected and that therefore it should not be treated as a shortfall (such that the penalty would be abated).

Line 55: Here, it really is a matter of straight math. If Line 54 is completed correctly with a “$0”, as indicated above, then Line 55, too, will be $0. Because again, the whole point is to make the case that, due to the corrective action, there was no failure to take the RMD… at least if the IRS approvals the penalty waiver request.

It’s also notable that, unlike many other types of IRS penalties, an individual does not have to pay the 50% penalty first, and then ask for relief and the money back. That used to be the case, but the procedure was changed more than a decade ago. Since 2007, prior payment of the 50% penalty is not required, and it is generally advisable not to make such payments voluntarily.

Example #4: Frank is a 72-year-old retiree who is the owner of a Traditional IRA and a 401(k). 2018 was the first year in which Frank had required minimum distributions (for both accounts), and while Frank fully satisfied his $15,000 IRA RMD, he failed to take any distributions from his 401(k) plan, where he had a $10,000 RMD due as well.

Recently, Frank’s plan notified him of his missed RMD, and Frank immediately took a distribution of $10,000 to “make up” the missed amount.

Accordingly, here’s how Frank should complete a 2018 Form 5329 to request relief from what would otherwise be a $5,000 = $10,000 x 50% penalty.

Line 52: “10,000”. Note that even though Frank’s cumulative RMDs for 2018 totaled $25,000, he successfully satisfied the RMD for his IRA. Thus, only the $10,000 RMD that was owed from the 401(k) need be included here.

Line 53: “$0”. Simple enough. Frank took $0 out of his 401(k) during 2018.

Line 54: “$0”, and to the left of the line on the dotted line, it should say “RC ($10,000).” Remember, this is the place where mistakes are often made. Despite what the actual language on Line 54 says, if you’re seeking relief from the 50% penalty, this should be “$0”!

Line 55: “$0”.

Historical 5329 Forms

Once complete, all necessary Form 5329s can be filed. If an RMD shortfall was caught and is being remedied early in the following calendar year, and before the tax return for that year is filed, the form can be filed along with an individual’s Form 1040. For instance, if a 2019 RMD shortfall was discovered and “corrected” in January of 2020, a 2019 Form 5329 requesting relief from the 50% penalty for that error should be completed and submitted whenever the taxpayer files their 2019 Form 1040 by April 15th of 2020 (or October 15, 2020 if on extension).

Many times, however, RMD errors are discovered long after the return for a tax year has been filed. Indeed, oftentimes such mistakes stretch back several years – and sometimes over a decade – before they are recognized and rectified. In such situations, the necessary Form 5329s can be filed by themselves, as standalone forms. (Note: Standalone Form 5329s cannot be electronically filed, though. They must be submitted via mail to the IRS at the location where the individual would paper file their Form 1040.)

Notably, the “making up” and correcting of prior-year RMD shortfalls does not, by itself, require a taxpayer to file an amended return for the years in question. Those returns were, and remain correct (absent other, unrelated errors)! Because individuals are cash-basis taxpayers, which means that they report income when it is received. And if an individual is taking make-up RMDs now, it is precisely because they were not taken correctly during past years, and instead should be reported when actually taken.

Thus, absent a hole in the space-time continuum that allows an individual to travel back and take any missed RMDs in “real time” (In which case, one has to wonder, are/were the RMDs ever even missed? Ooooo. That’s deeeeep), the corrected distributions are income now, when they are taken. Thus, all of the income from all of the corrected distributions would be reported on an individual’s current-year tax return, when filed.

Attach A Letter Of Explanation To Each Form 5329 Submitted For Penalty Relief

Click Here To Download Our Sample Letter Of Explanation For Missed-RMD Penalty Relief Alongside Form 5329

Form 5329 provides the IRS with the hard data, but it doesn’t, by itself, provide a taxpayer with a way to explain to the reasonableness of both their error and their corrective measure to the IRS. That part must be accomplished by attaching a note to Form 5329 to make the taxpayer’s case for penalty relief.

In general, the note should be short, and to the point. It should include the years in which RMDs were missed, the amount of the RMD shortfall in each year, the corrective actions taken, and the reason the errors occurred in the first place. See our Sample Letter Of Explanation For Missed-RMD Penalty Relief Alongside Form 5329.

There Is Generally No Statute Of Limitations For The 50% Missed-RMD Penalty

One common misconception among both the public, as well as many tax professionals, is that if the IRS doesn’t “catch” the missed RMD within three years, the 50% penalty for an RMD shortfall is unenforceable due to statute of limitations constraints. The Tax Court, however, has largely rebutted this notion in Paschall v. Commissioner.

Three-Year “Regular” Statute Of Limitations And The Six-Year Extended Statute For Substantial Understatement Of Income

In general, there is a three-year statute of limitations for the IRS to make changes to a taxpayer’s return. Which means, in essence, if the IRS discovers an error after the time window, it’s too late for the IRS to try to apply any applicable tax penalties. The three-year window starts on the later of the due date of the return, or on the date the return was actually filed.

The general three-year statute of limitations is extended to six-years (from the due date of the return or date the return was filed) when there is a “substantial understatement of income,” which is defined as a shortfall in reported income by more than 25% of an individual’s gross income. In addition, as a result of the Surface Transportation and Veterans Health Care Choice Improvement Act of 2015, an overstatement of an individual’s cost basis that has the effect of a more-than-25%-understatement-of-income also extends the statute to six years.

However, there is no statute of limitations in the event of fraud (i.e., it’s not permissible to deliberately fraudulently misstate the applicable income or deductions in the hopes that the IRS simply won’t catch it until after the statute of limitations).

Paschall v. Commissioner Case Determines That Form 5329 Is A Tax “Return”

As noted above, the general statute of limitations runs three years from the later of the due date of a taxpayer’s return, or the date on which he/she files the return. Thus, if a return is never filed, the statute of limitations clock never begins to toll!

What, however, constitutes a “return” in the first place? This was the central question in the Paschall case. In brief, Robert Paschall engaged in some “creative” Roth IRA conversion “planning” in 2000 (led by a major U.S. accounting firm). The “planning” was meant to allow Paschall to effectively transfer the value from his traditional IRA to a Roth IRA, without paying any income tax. Clearly, this “strategy” doesn’t pass the “smell test.” Nevertheless, and despite being aware of the transactions within the “regular” three-year statute of limitations, it took the IRS some eight years to address the matter. And in February and July of 2008, the IRS sent Paschall notices of deficiency for excess contribution penalties related to the “Roth Restructure” for years 2002 - 2006.

Not surprisingly, Paschall’s attorney’s main argument to the Tax Court was centered around the statute of limitations. That Paschall, he said, had timely filed tax returns for each of the tax years in question. Thus, by the time the IRS issued its notices of deficiency (in 2008), he argued, the IRS was precluded from assessing tax liabilities related to 2002 – 2004 (past the statute of limitations time window).

The IRS, however, rebutted Paschall's argument, stating that, although Paschall had timely filed their Form 1040 for the years in question, they had not filed Form 5329 for any of those years. It further argued that Form 5329 should not be considered “just” a form, but rather, its own “return,” and that, by failing to file that return, Paschall had not started the statute of limitations clock for any of the taxes/penalties associated with that tax return.

The Tax Court agreed that Form 5329 constitutes a “return” unto itself (and isn’t merely a form of another return), and upheld the IRS’s assessments of well over $500,000 in penalties… before interest that also had to be stacked on top (which at that time, was not the nominal amount it is today!).

Impact Of Paschall On RMD Errors

As its name, “Additional Taxes on Qualified Plans (Including IRAs) and Other Tax-Favored Accounts”, indicates, Form 5329 covers the gamut of penalties that apply to retirement accounts, from the 6% excess contribution penalty, to the 10% early distribution penalty, to, of course, the 50% penalty that applies to an RMD shortfall. As such, even though the matter at hand wasn’t specifically RMDs, the Tax Court’s ruling in Paschall has a significant impact for those who have missed an RMD as well.

Simply put, if you missed a required minimum distribution, but haven’t filed Form 5329 for the specific tax year in question, you’re not safe from the IRS. And you never will be.

To make matters worse, Form 5329 isn’t one of those forms you typically end up filing from year to year. In fact, unless you “know” you have a penalty that should be reported on the form, it’s typically not filed at all. And while it is theoretically possible to file the form with all “$0s” each year along with an individual’s Form 1040 (and other required tax forms) – just to try to start the statute of limitations for any/every year as a “just in case” effort – that might draw some attention unto itself. Plus, if out of all the many IRS forms you could file in any given year, you just happen to choose only Form 5329 to file with “$0s” each year, and the IRS later finds that you’ve been hiding penalty amounts, you open yourself up to a stronger fraud argument from the IRS.

Thus, in most situations where Form 5329 is not filed, the IRS can, in theory, discover a taxpayer’s missed RMDs many years after the fact, and then go back and retroactively assess the 50% penalty. And if the IRS wanted to, it could also hit the same taxpayer with failure-to-file (the Form 5329) penalties, and failure-to-pay (the penalty that should have been reported on Form 5329) penalties, and interest on those “underpaid” penalty amounts that weren’t paid in the original year they would have been due! If the deficiency is bad enough, the accuracy-related penalty (for materially misstating the total amount of taxes-plus-penalties owed) could find its way into the mix as well.

Clearly, not correcting and self-reporting RMD errors when they are discovered is a risky game. And quite honestly, given the rate at which the IRS tends to approve abatements of the 50% penalty when the correct actions are taken, it’s also a fool’s game.

Post-Death RMD Shortfalls For Inherited IRA (And Other Retirement Account) Beneficiaries

While most retirement account owners (other than Roth IRA owners) become subject to RMDs once they reach age 70 ½, non-spouse beneficiaries of any retirement account (including Roth IRAs) must generally begin taking required minimum distributions almost immediately from their inherited accounts (with the first such RMD due by the end of the year following the year of death).

In the event that a beneficiary fails to take the correct RMD amount from an inherited retirement account, they should follow the same steps to rectify the error as original retirement account owners: identify the shortfall, distribute the shortfall, and report the shortfall and corrective distribution to the IRS using Form 5329.

Critically, though, the failure to take one or more required minimum distributions from an inherited retirement account does not preclude a beneficiary from “stretching” distributions. In other words, just because a non-spouse beneficiary fails to begin stretch distributions to avoid the dreaded 5-year rule doesn’t mean they’re automatically relegated to the 5-year rule for failing to begin the stretch in a timely manner.

Rather, when “the stretch” is the default – as it is for virtually all inherited IRAs and some inherited employer-sponsored retirement plans – the stretch remains the distribution regime, even when required minimum distributions are missed. Thus, a beneficiary who has missed one or more RMDs from their inherited account should simply make up whatever distributions were missed, and pick up the stretch at that point, as if they had been correctly taking distributions all along.

(Note: While some employer-sponsored retirement plans use the stretch as the default distribution schedule for non-spouse beneficiaries, many require such beneficiaries to distribute assets much sooner, often within five years. In such instances, the beneficiary can take timely (directly) roll the funds to an inherited IRA that allows the stretch (by the end of the year after the year of death). If, however, the funds remain in the plan past December 31st of the year following the year of the plan participant’s death, then the beneficiary is subject to the plan’s distributions rules (even if the funds are later moved to a stretch-allowing account).

Beneficiaries Should Take Corrective Action To Rectify A Decedent’s Missed RMDs From Before Death

Occasionally, the mistakes of a retirement account owner are not discovered during their lives, but rather, by loved ones after their death. In such instances, it’s important to understand that, while the 50% penalty is applicable to the decedent’s estate and does not carry over to the beneficiaries, it is the beneficiaries who must take the corrective distributions to remedy the situation.

Because technically, once a retirement account owner dies, everything in the account belongs to their beneficiary. There is no way, or mechanism, for an executor to pull missed distributions back into an estate. In fact, given that retirement assets generally pass by contract and not via the probate process, the executor of an estate has no control over those assets whatsoever (in that capacity – though oftentimes an individual’s executor is also one of their beneficiaries)! Thus, the only people who can make up the decedent’s missed RMDs are the beneficiaries of the decedent’s account (who control the account after death).

Of course, since the 50% penalty still “belongs” to the decedent, the executor should coordinate with the beneficiaries to ensure that such distributions are made, and that the proper Form 5329s are filed on behalf of the decent with the IRS to request an abatement of 50% penalty on behalf of the decedent.

While this might seem like overkill (pardon the expression!) for a dead person’s past tax mistakes, the executor him/herself should be certain to take such action. Because as noted above, the IRS can generally assess the 50% penalty retroactively for an indefinite period of time, because the form (return) on which it is reported is not generally filed. That penalty is a debt of a decedent’s estate, which an executor is responsible satisfying before closing the estate and distributing assets to beneficiaries of the estate. Thus, if assets are passed to beneficiaries, and the IRS subsequently identifies the missed-RMD error on their own, they could seek to recover such penalty amounts from the executor themselves if there are no longer assets in the estate via a process known as transferee liability!

RMD errors are some of the most common mistakes made by retirement account owners and beneficiaries. Between the timing, calculation, and location requirements associated with RMDs, it’s easy to make a mistake.

But while the 50% penalty is rather harsh, the abatement (i.e., the IRS granting a waiver) of the penalty is actually quite likely, when the appropriate steps are taken. The key is to avoid the natural temptation to “let it slide,” or to “let the IRS figure it out on their own.” As the IRS is much less likely to be gracious when they make the discovery of the error themselves (rather than the taxpayer voluntarily coming forward to self-report a correction).

And again, the danger of “letting sleeping dogs lie” in the case of missed RMDs is that, unlike many other tax matters that are appropriately “covered” by the filing of Form 1040, RMD mistakes and the penalties associated with them are reported on Form 5329, a form which is rarely filed. Absent the filing of that form, penalties can be assessed indefinitely because the statute of limitations never begins.

Thus, the only logical course of action when an RMD error is discovered is to take action to fix it. Take the missed distributions as soon as possible, and seek an abatement of the 50% penalty from the IRS by filing Form 5329 with an accompanying explanatory note. The result will almost always be favorable when done properly, as, in practice, the IRS is often quite generous regarding good-faith errors of RMDs that were promptly rectified when discovered.