Executive Summary

Using an S corporation to reduce self-employment taxes – by splitting the income into a “reasonable compensation” salary and S corp dividends – is a popular strategy that financial advisors recommend to clients in a wide range of businesses. And in point of fact, it’s actually a viable strategy for financial advisors to use for their own advisory firms.

However, the recent Tax Court case of Fleischer v. Commissioner (TC Memo 2016-238) serves as a reminder that while advisory fees can be paid to an S corporation and partially passed through as a dividend to reduce taxation, the strategy does not work for insurance and investment commissions. In Fleischer’s case, the Tax Court invalidated his efforts to assign and transfer both his LPL investment commissions and MassMutual insurance commissions into his S corporation, finding instead that he should have claimed them as personal income on his Schedule C (and paid self-employment taxes on all of it).

The fundamental challenge is that, in order for a corporation to legitimately claim income, it has to actually control the contractual engagement to earn in the income. Which in the case of insurance and investment commissions, is generally impossible, because securities and state insurance laws require that commissions be paid directly to the individual. The only way an entity can legitimately receive the income is if the entity itself is registered as a broker-dealer or an insurance agency (and then contracts directly for the commission income), which alas may be common for an RIA but is usually not feasible for a broker-dealer or insurance agency due to regulatory and compliance costs.

Nonetheless, as the Fleischer case indicates, the fact that establishing a bona fide broker-dealer or insurance agency isn’t economically feasible in most cases doesn’t change the underlying requirement of the tax law – which is that if an individual earns income personally (including investment or insurance/annuity commissions), that person must report the income for tax purposes, and can’t simply transfer it into a business account and issue a 1099-MISC to the S corporation and expect it to be honored by the IRS!

Requirements For Securities And Insurance Commission Payments

It is a fundamental requirement that for an individual to receive a commission for the sale of a securities product, he/she must actually be registered as a representative of a broker-dealer. And to ensure that this rule is honored, FINRA Rule 2040 states that no payment of compensation may be made to an entity at all, unless the entity itself is registered as a broker-dealer as well.

Similarly, most states also limit the payment of insurance commissions to either individuals licensed as an insurance agent, or entities that are properly registered as an insurance agency or insurance brokerage firm. Splitting insurance commissions to/with non-licensed entities is generally forbidden as well.

The ultimate purpose of these rules is to prevent individuals from circumventing registration rules by trying to route their (securities or insurance) commissions through non-registered entities. Instead, commissions must be paid directly to (registered/licensed) individuals, and the only entities that can be registered must honor the compliance requirements that apply to those types of (broker-dealer or insurance agency/broker) entities. Thus, non-licensed individuals have no path, directly or indirectly via an entity, to get paid commissions they shouldn’t be entitled to as non-registered persons.

The caveat, however, is that always receiving payments individually is not always ideal from a tax planning perspective. Because income that is paid directly to an independent broker or insurance/annuity agent will have to be fully reported as self-employment income (net of any expenses) for tax purposes. Whereas if the income was paid to an entity – in particular, an S corporation – it would potentially be possible to pay a portion of the income out as S corp dividends, not subject to self-employment taxes.

But as a recent Tax Court case illustrates, the fact that commission income must be payable to an individual also means it must be reported by that individual for income tax purposes; as desirable as it may be, it’s not permissible for brokers or insurance agents to try to “reassign” commission income to an S corporation, just to avoid or minimize self-employment taxes!

The Tax Court Case Of LPL Broker Fleischer v. Commissioner (TC Memo 2016-238)

In the recent case of Fleischer v. Commissioner, TC Memo 2016-238, Ryan Fleischer was a Series-licensed independent broker with LPL (structured as an independent contractor), and also an insurance agent with MassMutual for fixed insurance contracts (again as an independent agent).

In addition to being individually licensed as a broker and agent, Fleischer also had an S corporation, called Fleischer Wealth Plan (FWP), for which Fleischer was the sole shareholder and officer, and with which he had an “employment agreement” to perform duties as a financial advisor.

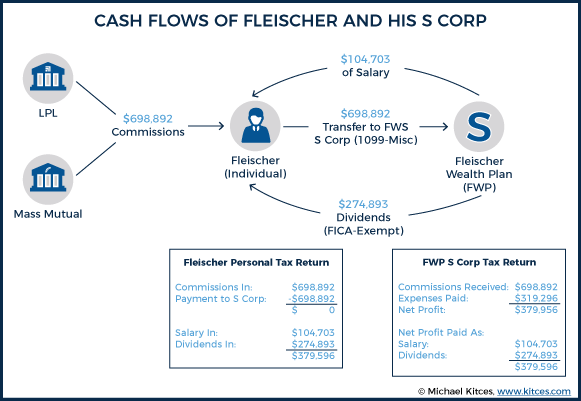

In 2009, Fleischer received a total of $147,617 of commissions from LPL and MassMutual, which he reported as income for his S corporation. The business netted $46,775 after expenses that year, of which Fleischer then paid himself $34,851 as salary, and took $11,924 as a dividend not subject to self-employment tax. None of his $147,617 of income was reported on his personal Schedule C.

In 2010, Fleischer received $284,963 of insurance and brokerage commissions. He claimed all $284,963 as an “expense” on his Schedule C – netting out to zero – and that even though they’d originally been paid to him, the commissions were all income of FWP, his S corporation. Overall that year, FWP generated $289,201 of total revenue, the business netted $182,498 after expenses, and Fleischer then paid himself another $34,856 as salary, taking the remaining $147,642 as a not-employment-taxed dividend.

In 2011, the process repeated. Fleischer received another $266,292 of combined LPL and MassMutual commissions, and again claimed a matching $266,292 of “expenses” for a net profit of $0 on his Schedule C. The commissions (of $266,292) were again reported as gross revenue to the S corporation, from which then paid Fleischer $34,996 of salary, and $115,327 of pass-through dividends, after deducting his (valid) business expenses.

Across all three years, Fleischer showed a net Schedule C income of $0, while the S corporation’s net profits (after Fleischer’s salary) were reported on a Form K-1 as pass-through income and claimed on Schedule E of Fleischer’s personal tax return instead. Cumulatively, Fleischer took $104,703 of salary (subject to payroll taxes), and $274,893 of pass-through dividends not subject to employment taxes.

Unfortunately, though, the IRS caught wind of the situation – ostensibly through a random audit – and upon evaluating the situation, noted that since all the commissions were paid to Fleischer directly (and not the S corporation) that the income should have all be reported directly by Fleischer (on his Schedule C) and not via the S corporation and its pass-through to Schedule E.

The key difference – if the income had been (properly) reported on Schedule C, all the income would have been subject to self-employment taxes. By contrast, with the S corp structure, there was $274,893 of (pass-through dividend) income never subject to payroll/self-employment taxes. Accordingly, IRS issued a deficiency notice that Fleischer owed $41,563 of self-employment taxes across all three years.

Limitations On Shifting Personal Commissions To A Related S Corporation

The key issue in the Fleischer case is that, under long-standing principles of taxation, income is taxed to the person who earned it. This rule avoids people simply shifting and ‘assigning’ income at will, which could otherwise be used for substantial tax avoidance, particularly in our current world of progressive tax rates. For instance, if income could be shifted so easily, those in high tax brackets could just distribute income across multiple family members in lower tax brackets to reduce their tax bill, or even just create a series of corporations and split the income evenly across as many entities are necessary to keep them all within the bottom (corporate) tax bracket.

Notably, determining who “earned” the income can be more complex in situations where there’s a corporation and an employee who does the “work” that generates the income. In the logical extreme, income could never be taxed to a corporation, because it’s always the human being employed by the corporation that is actually doing the work to “earn” the income.

To distinguish when an individual earns money in his/her personal capacity instead of merely as the employee of a business, the tax code looks to who controls the earning of the income. Thus, in a standard corporation-employee scenario, the employee may do the work, but the corporation has the contractual agreement with the client and ultimately controls whether the contract will be fulfilled and controls how services will be rendered. Which means the income would be taxed to the corporation (even though the employee “did the work”).

Specifically, under existing case law and Treasury Regulation 31.3121(d)-1(c)(2), to claim that the corporation is the controller of the income, “the individual providing the services must be an employee of the corporation whom the corporation can direct and control in a meaningful sense”, and “there must exist between the corporation and the person or entity using the services a contract or similar indicium recognizing the corporation’s controlling position”.

Except the problem in the case of Fleischer – or any independent B/D or insurance/annuity agent – is that there is no contract between the corporation and the person paying for the services (in this case, the B/D or insurance company for whom the broker/agent is a representative), because the actual engagement is between the broker-dealer (or insurance company) and the individual broker/agent who is (individually) licensed to do the work as a registered representative or insurance agent. The broker’s S corporation is not a party to the engagement with the insurance company or broker-dealer (much less a controlling one!).

In other words, if Fleischer’s S corporation was contracted directly with LPL or MassMutual, such that the S corporation was going to be the insurance agent or registered representative (and Fleischer himself was merely an employee), it might have been permissible for the S corporation to claim the income. A similar 1991 Tax Court case – Sargent v. Commissioner – was decided this way, where two hockey players formed an S corporation that established player contracts directly with the hockey team, and the team then paid income directly to the S corporation (which in turn remitted salaries to the hockey players as employees).

Unfortunately, though, given the licensing requirements applicable to broker-dealers (and their registered representatives) or for insurance agencies (and their insurance agents), for LPL and MassMutual to have paid Fleischer’s S corporation FWP directly (rather than Fleischer himself), Fleischer would have had to form a broker-dealer entity (and/or insurance agency), with all the costs, capital requirements, and compliance obligations that go along with it. Which Fleischer himself noted wasn’t very feasible.

Nonetheless, the conclusion of the Tax Court was straightforward: if FWP wasn’t directly a party to the commission agreements with LPL and MassMutual, it couldn’t claim the commission income. Instead, Fleischer was the licensed broker and agent, and thus should have claimed the income directly. And as a result, he was found liable for the $41,563 of unpaid self-employment taxes as calculated by the IRS.

Are Brokers And Insurance Agents Running Afoul Of The Fleischer Case Now?

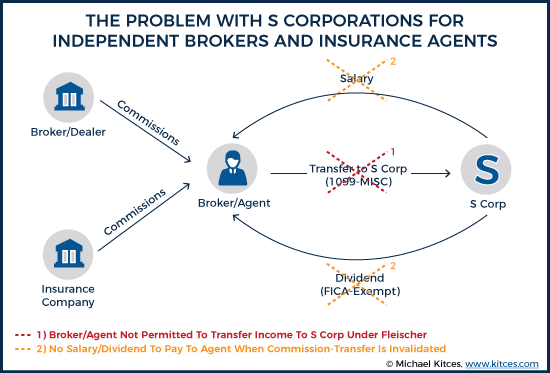

Notwithstanding the Tax Court’s very straightforward conclusion that an S corporation shouldn’t claim investment or insurance commissions as income if that income isn’t actually paid to the S corp in the first place, the Fleischer strategy appears to be engaged in frequently amongst many independent brokers and insurance agents.

The standard scenario, akin to Fleischer, is that the individual broker/agent receives commissions directly, and then immediately moves those dollars into the S corporation’s bank account, claiming a deduction (and likely issuing a 1099-MISC) for all the money transferred to the S corp, for which the S corporation subsequently splits the net profit payments back to the advisor as part salary, and part dividend. And the broker/agent saves tax dollars to the extent of the self-employment taxes not due on the dividend portion of the income.

Except the case of Fleischer v. Commissioner makes it clear that this is not permitted! Again, if the S corp isn’t contractually engaged with the broker-dealer or insurance company to receive the securities or insurance commissions directly, it cannot claim them as income. The mere fact that the advisor may be transferring the money to the corporate account, issuing a 1099-MISC to the S corporation, and claiming a deduction, doesn’t make it legitimate or binding, when there’s no actual legal basis for transferring the income in the first place. In the Fleischer case, it wasn’t a matter of whether Fleischer “properly” transferred the income or properly reported it; the conclusion of the court was that the income should have all been on his personal Schedule C. Period.

Practical Implications Of The Fleischer Case

Unfortunately, the outcome of the Fleischer case may be bad news to a lot of independent brokers and insurance agents, currently engaged in a similar strategy using an S corporation to reduce their self-employment taxes!

Of course, the reality is that the Fleischer case didn’t actually cause a change in the tax rules; instead, it merely reiterated existing laws as they stand. But it does reaffirm that brokers and insurance agents transferring commissions to their S corporation (to shift the income for tax purposes) is not permitted. And the fact that the IRS caught Fleischer in the act, and defended it all the way to Tax Court, suggests that the IRS now has the issue more squarely on their radar screen and is ready to pursue it.

Notably, the challenge for advisors shifting compensation to an S corporation is unique to those working under a broker-dealer or insurance agency, but not those who own an independent RIA. Because in the case of an RIA, it really is possible to register the S corporation entity directly as a Registered Investment Adviser (at a drastically lower cost than what it takes to establish a broker-dealer). And once the RIA is registered, clients can engage the firm directly and pay fees directly to the RIA, which in turn can pay a salary to the advisor/owner (who ideally should have a formal employment agreement in place to substantiate the arrangement as an IAR of the RIA), and then pass through the remaining income as a (not-self-employment-taxed) dividend. Notably, it’s still necessary for the advisor to be paid “reasonable compensation” salary.

The Fleischer scenario is also a moot point for brokers who operate under an employee model and are treated as wage employees of the broker-dealer (or insurance company). Because in that case, the broker-dealer itself is already paying FICA payroll taxes as a part of the W-2 wages to the broker, and there is no self-employment tax obligation (nor any role for an external S corporation in the first place).

But in the case of those working for an independent broker-dealer (or as independent insurance or annuity agents), the challenge remains that commissions can only be paid directly to an individual, unless the S corp entity itself is established as a broker-dealer or insurance agency, which alas usually just isn’t economically feasible.

It’s important to recognize, though, that the Fleischer case doesn’t necessarily mean no dollars could ever be legitimately paid to a related S corp. For instance, in a situation where the S corp actually has other staff employees, the employees could be employed by the S corp, and the advisor could pay the S corp for those support staff services. Of course, that doesn’t necessarily generate any employment tax savings, since that staff compensation would have been deductible anyway. But it might be appealing for some partial liability protection purposes, and avoids what would otherwise be a problematic scenario where the S corporation has all the (employee) expenses but no income, producing not-currently-deductible “business” losses that couldn’t be netted against Schedule C income. And in some cases, there might at least be indirect tax savings, such as in a situation where the advisor lives in a higher-tax state while the S corp is in a lower tax state (that doesn’t have a special gross receipts tax on S corps).

Example 1. Jeremy generates $450,000 of gross commissions, and has three support staff members to which he pays a total of $200,000 of salary and related employee benefits. While Jeremy is directly licensed with his broker-dealer, his employees are all employed by his related advisory firm S corporation. On his personal tax return, Jeremy claims a $200,000 business expense for “Advisor Support Services” to his related S corporation, which then uses the $200,000 of “income” to pay the employees. The end result is that Jeremy’s Schedule C shows $450,000 of gross income and $250,000 of net income (after the expenses paid to the S corporation), and the S corporation shows $200,000 of gross revenue and $200,000 of expenses for net income of $0.

Notably, the end result of this example is not any improvement in Jeremy’s personal tax situation – as he could have paid the employees directly and deducted the $200,000 of staff expenses on his Schedule C for the same net income. But if he wants an S corporation in place – perhaps because it generates other income that can be paid to the S corporation, and he wants to group it all together – the $200,000 should be recognized, because he’s not merely “transferring” income, but actually paying for bona fide services (albeit to a related business he owns).

In point of fact, it’s also fair to recognize that if a third-party S corp “service” business were working with the advisor, it might charge a reasonable markup to generate a profit as well. After all, if the broker had to hire a third-party outsourcing solution, it could reasonably charge a markup to actually make a profit over its staff costs, not merely price them as a pass-through. Which means it may be possible to at least slightly shift some additional amount of income to the S corporation (and reduce self-employment taxes).

Example 2. Continuing the prior example, Jeremy might recognize that if he had to hire a third-party outsourcing firm on the open market, it would reasonably have charged $230,000 for his “service contract”, allowing for a 15% profit margin on the engagement. Accordingly, Jeremy agrees to pay (his related business) $230,000 for his “advisor support services”. This reduces his Schedule C income to just $220,000, and creates a $30,000 profit for the S corporation (since it is “paid” $230,000 but only has $200,000 of actual employee expenses).

In this case, Jeremy’s total income is still $220,000 + $30,000 = $250,000 (the same as an Example 1), but the $30,000 of S corp profits could be taken as a pass-through dividend, which means the $30,000 is still taxed as ordinary income but not subject to self-employment taxes. Given Jeremy’s income (and that he’s above the Social Security wage base), this would produce a moderate $30,000 x 2.9% = $870 of self-employment tax savings.

The fundamental point remains, though, that paying a portion of a broker’s (or insurance agent’s) income to an S corporation for services (even if it’s a related S corp he/she owns) is one thing, but simply transferring/assigning income from yourself to your S corporation is another. Because even if you take back what would have otherwise been a “reasonable compensation” salary for your work under the S corp, it doesn’t matter, because the S corp wasn’t contracted and engaged to earn the income in the first place.

Given the popularity of this strategy in recent years, brokers and insurance/annuity agents who have been engaging in it anyway, and may have been running afoul of this issue in the exact manner that Fleischer did, may want to contact their accountants to consider whether/how to rectify the situation (potentially retroactively, as well as going forward). Especially since, as the Fleischer case notes, this is an issue that appears to now be on the IRS’ radar screen!

So what do you think? Does the Fleischer ruling impact you? Do you have any clients with S corps that may be similarly impacted due to licensing within their industry? Do you think it's still worth using S corps for other reasons? Please share your thoughts in the comments below!