Executive Summary

In the early days of insurance broker-dealer recruiting efforts, it was so lucrative to attract new brokers who could sell the broker-dealer’s proprietary products to their clients, that insurance broker-dealers began to outright pay for new brokers to join the firm… in the form of a loan that would be forgiven as long as certain proprietary product sales requirements were met. Over time, these “forgivable notes” have morphed from being contingent on the sale of proprietary products, to overall maintenance (or growth) of the broker’s production, to (as regulators began to crack down on the conflicted incentives) simpler time-based contingencies. Yet even as the requirements have changed, the underlying structure remains – where many broker-dealers today try to attract advisors to switch firms by offering potentially substantial upfront recruiting “bonuses” in the form of forgivable notes… in the hopes of making back that recruiting cost (and then some) from the advisor’s clients.

In this guest post, Jonathan Henschen – president of Henschen & Associates, a recruiting firm that specializes in helping advisors find and match themselves to the right independent broker-dealer when making a switch to a new platform – discusses the history and mechanics of forgivable notes, some of the ethical concerns they raise for brokers and their clients, and how the evolving landscape of the industry is encouraging broker-dealers to reconsider their incentive structures (and advisors to reconsider whether forgivable note recruiting bonuses are worth their long-term consequences to clients).

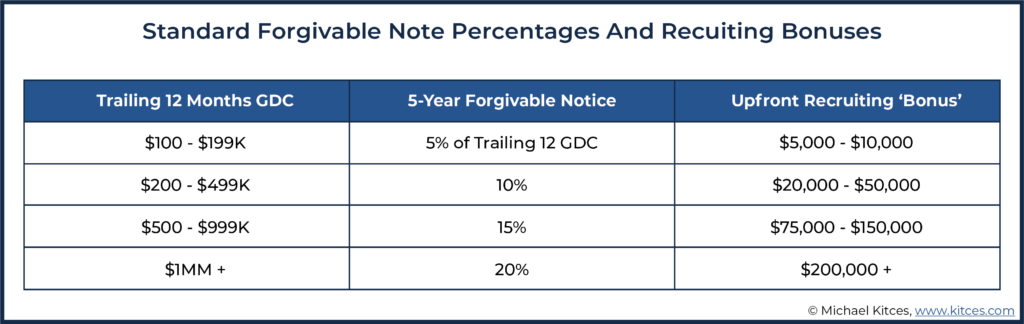

Typically, forgivable notes are structured as a percentage of the broker’s trailing 12-month Gross Dealer Concession (GDC), and have evolved from notes (issued prior to 2000) that ranged from 5 – 20% of trailing-12-month GDC and were forgiven over five years, to notes as high as 40% of trailing-12-month GDC that are forgiven over seven years. Throughout, though, the core principle has remained the same – the advisor receives an upfront “bonus” to join the new broker-dealer, but it is actually in the form of a loan, that the advisor will have to repay (i.e., the unpaid balance of the loan) if certain requirements are not met over time.

Today, forgivable notes have become so ubiquitous that many advisors who switch broker-dealer firms consider forgivable notes as a required component to their job offer. Yet the reality is that broker-dealers only offer such “bonuses” because it is profitable to do so in the long run… which means advisors and their clients must bear higher costs in order for the broker-dealer to recover its own costs!

Specifically, the particular revenue sources driven by broker production that help to recover the cost of forgivable notes include brokerage account transaction charges (often substantially marked up over the raw costs to increase the profit margin of the broker-dealer), revenue sharing with product vendors (e.g., mutual funds, variable annuities, REITs, alternative investments, and to some extent ETFs), markups on No Transaction Fee (NTF) mutual fund expense ratios, markups on third-party money managers, proprietary advisory platforms, advisory administrative fees for advisory accounts managed by the brokers themselves, platform fees for holding TAMP assets directly at the TAMP (which, without this extra fee, would otherwise avoid the broker dealer markup for being held within the TAMP provider), and platform fees for holding advisory assets at third-party RIA custodians (e.g., Schwab, Fidelity, TD Ameritrade). Some or all of which are additional layers of expenses that the advisor and their clients may not have had to pay if not pursuing a broker-dealer’s forgivable note recruiting bonus.

In fact, when determining how much to pay into forgivable notes in today’s marketplace, broker-dealers consider the advisor’s product mix and asset levels, to determine a forgivable note amount based on a profitability matrix that each broker-dealer establishes based on its various profit centers imposed and the actual revenue generated from various asset classes (influenced more by assets held in brokerage accounts or managed by the broker dealer, and less in assets held away).

Notably, though, a new crop of some fiduciary-friendly brokers are beginning to emerge, that aim to compete specifically by limiting the markups and fees (which aren’t necessary if substantial forgivable notes aren’t being paid in the first place).Instead of forgivable note bonuses, these firms often recruit brokers with more limited incentives, that may still include some transition expenses (e.g., ACAT transfer expenses to move assets over to the new broker dealer, registration costs, and broker transition/startup costs), payback loans to cover larger set-up expenses incurred by the new broker (e.g., new office space), and providing 100% of GDC for a short period (e.g., 3-6 months) to accommodate initial cash flow for the new broker… but without the need to place as much burden on the advisor’s costs to their clients.

Ultimately, while forgivable notes can be attractively alluring to brokers seeking new broker-dealer firms, the cost of recovery for broker dealer firms to offer these notes, in the end, is passed onto the client who (often unknowingly) may pay heavily in a wide array of fees and expenses related to proprietary advisory platforms. And while broker-dealers, like any other business, are entitled to generate revenue for the services they provide, the rising attention on fiduciary practices and the recent transition by many large custodians to ‘zero-commission’ trades on stocks and ETFs are pressuring many to rethink how they structure their incentive programs and profit centers, lest their advisors lose clients as the layers of additional cost risk rendering them uncompetitive in the current marketplace. The bottom line, though, is simply to understand the bottom line – that there’s no such thing as a “free lunch”, and that broker-dealer recruiting bonuses come with real costs that must be carefully considered.

The Emergence Of Broker-Dealer ‘Recruiting Bonuses’ In The Form Of Forgivable Notes

Prior to the 1990s, broker-dealers that were recruiting new brokers typically would cover advisor transition expenses plus incidentals as a part of the deal. But as competition for attracting brokers heated up with the booming 1990s, some broker-dealers began to offer an upfront “bonus” for joining the firm… in the form of what was technically a loan to the broker, that would be forgiven (in essence, “earned”) over time by staying with the firm and/or hitting certain growth or retention metrics. However, the payment was technically a loan, as evidenced by a loan “note” that came due for repayment if the required metrics were not met… and thus simply became known as a “forgivable note”.

It was primarily the insurance-owned broker-dealers that drove the forgivable note trend, with Jackson National broker-dealers being the most aggressive in using upfront dollars to entice advisors to join their firm… because, as a manufacturer of insurance products, the insurance-owned broker-dealer could make back its recruiting bonus with additional sales of its proprietary products (and if the deal didn’t work it, the broker-dealer could recover the payment as the note came due).

My first recruiting experience in the late 1990s was as the Midwest recruiter for one of the Jackson National broker-dealers, National Planning Corp. Our recruiting manager explained that they could pay 30% of trailing revenue for the purchase of an entire broker-dealer – taking on the firm’s brokers and clients, and the associated branch office locations, infrastructure, and home office staff of the firm – or they could simply bring on advisors directly, with an upfront bonus in the form of a forgivable note and pay 10-20% of the broker’s trailing 12-month revenue. At the time, the firm preferred to offer forgivable notes directly to brokers – rather than acquire the parent broker-dealers – because in the end they were only really interested in the advisors and client assets anyway, and had no need for the brick and mortar branch offices and potentially redundant home office staff.

Notably, at the time insurance-owned broker-dealers often operated at a loss (frequently because of the high volume of FINRA fines they paid because of their sales practices and/or failure to sufficiently supervise those sales practices). The real money was made via proprietary products (e.g., the insurance company’s own variable annuities) sold through the representatives at their broker-dealers. Accordingly, in the early to mid-1990s, the insurance broker-dealers would incentive their brokers into the company’s proprietary products, paying higher commissions on them, setting percentage requirements for their proprietary products (e.g., 30% of all production must be in company product), and excluding competing products from the available product shelf. By the late 1990s, though, regulators grew uncomfortable with these overt methods of steering product sales, favoring an even playing field for product choices over ones that gave disproportionately higher payouts for using company products.

How First-Generation Forgivable Notes Evolved Away From Proprietary Products To General Production

However, the insurance companies were clever and simply found more subtle ways to direct advisors to sell their proprietary products. For example, while they had to offer products from competing annuity and mutual fund companies (rather than limiting the available product shelf), they would instruct wholesalers at competing product companies that they could only respond to inquiries from their advisors, but could not initiate contact with their advisors, such that those who weren’t proactively looking for ‘outside’ products would never hear about the alternatives and only see the company’s own products highlighted in internal sales meetings. Broker-dealers also gave preferential placement to proprietary product ads and information throughout their websites, and when advisors went to the broker-dealer’s annual conference, proprietary products had high visibility, while key competing products were not invited to the exhibit hall.

By the late 1990s and moving into the 2000s, the standard forgivable note was payable over 5 years as a percentage of GDC (Gross Dealer Concession, measured as the broker’s trailing 12-month revenue with the broker-dealer), with higher bonus percentages of higher levels of production:

During the five-year note period, for most firms, the upfront bonus paid as a loan (i.e., the “forgivable note” itself) was forgiven one-fifth per year. Thus, if the advisor left the broker-dealer two and a half years into the note period, the advisor would owe half the note money to the broker-dealer.

Advisors would also typically be required to maintain production during the note period, such as sustaining Gross Dealer Concession (GDC) equal to at least 80% of the amount on which the note was based. So, if the note was based on $1MM of GDC (i.e., that was their trailing 12-month revenue from the prior broker-dealer), the advisor would need to maintain at least $800K/year of production (GDC) during the note period. If production dropped below the $800K requirement as of the note anniversary, the broker-dealer would charge interest on the note, extend the note period for an additional year, and/or reserve the right to call the note and ask for what was owed at that time (i.e., the remainder of the note that hadn’t already been earned and was still technically a loan from the broker-dealer to its representative).

The Jackson National notes were especially ‘hostile’ to the broker, in that they did not forgive the notes one-fifth per year like other broker-dealers. Instead, they applied the forgiveness primarily toward the end of the note period. If the advisor left the broker-dealer two and a half years after joining, instead of owing half the forgivable note money back to the broker-dealer, they could still owe 80% of the original note amount or more.

How Forgivable Note Recruiting Bonuses Increased And Extended In The 2000s

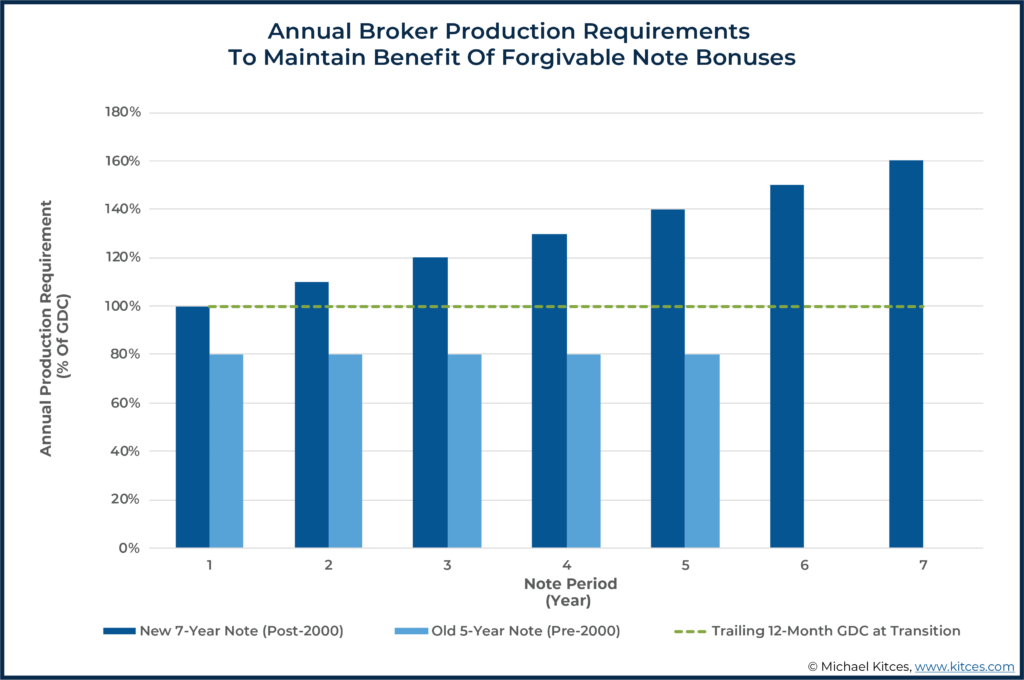

Jackson National broker-dealers led the way with even-higher upfront bonuses (i.e., larger note amounts) in the 2000s. These new notes offered 40% of trailing 12 months GDC, and an advisor with production as low as $200K GDC could request the higher 40% amount. This higher amount had more strings attached in terms of length of note period, and also production requirement—the advisor would be obligated to increase production during the seven-year forgivable note period to avoid being required to repay the recruiting bonus:

Notably, the end result of these higher GDC thresholds was that while the upfront notes seemed to be more lucrative for the broker switching firms – receiving a note amount of 40% of ‘just’ $200k of GDC, which in the past might have only received a 10% upfront bonus, the higher production requirements more than recovered this cost for the broker-dealer. After all, the ‘prior’ structure may have simply required that $200k producer to generate at least $160k/year of GDC for the subsequent 7 years, or a total of $1.12M in production, to keep their $20,000 forgivable note (which in practice was usually forgiven in just 5 years), while the new arrangement paid $80,000 to the broker but required $1.82M in production over 7 years, on which the broker-dealer might earn 15% or more (between its share of the grid, and back-end platform payments). Which meant the broker-dealer required an extra $700,000 of GDC, on which it might earn an additional $105,000 or more… in exchange for ‘just’ a $60,000 increase in the forgivable note. Not to mention that the broker’s production would likely include (and might be required to include) a sizable slice of the insurance company’s own proprietary products (on which the insurer would also profit as the manufacturer of the product, in addition to profiting at the broker-dealer level for its sale).

Unfortunately, though, these higher note amounts – maintaining 100% rising to 160% of GDC over 7 years – resulted in an increased incidence of advisors falling short of production minimums required on their note, triggering a forced repayment of the upfront bonus (as the ‘note’ came due as a loan). After all, independent representatives averaged a loss of 10%-25% of their production the year they changed broker-dealers alone – as inevitably not all clients switch and come along, and the transition itself is ‘distracting’ from new business development – so achieving 100% of the prior year production the first year at the new broker-dealer, let alone achieving the higher production numbers on subsequent years caused a large segment of advisors to fall short.

Not surprisingly, ethical issues started to surface as to whether appropriate investment decisions were being made for the client’s interest or for the representative’s interest as they struggled to meet the note requirements. Especially since many brokers, not realizing the stringency of the terms of the forgivable note, had already spent the upfront “recruiting bonus” and may not have had the financial wherewithal to repay the note a year or few later if their GDC growth hadn’t kept up.

The Reinvention Of Forgivable Note Recruiting Bonuses As Insurance Companies Exit

In the late 2000s into the 2010s, in the aftermath of the financial crisis, insurance companies started to shed themselves of their broker-dealers. A combination of factors spurred these sales, including:

- Lower profitability on insurance products as a result of a lower interest rate environment from the Fed’s quantitative easing

- Variable annuities that created large losses due to poor actuarial assumptions on living benefit riders that came due in the 2008-2009 market decline

- Less control on what products the representatives at their broker-dealers would choose as platforms became more ‘open’, and regulators that pushed for forgivable notes to be based only on time (and not production, having already previously limited having forgivable notes based on the use of proprietary products)

- Less appeal to broker-dealer ownership with its high litigation costs that mushroomed after the 2008/2009 recession

Filling the void left by insurance companies exiting the IBD channel, firms like LPL grew by purchasing many of these insurance broker-dealers (Pacific Life and Jackson National broker-dealers), but also the expansion of Private Equity ownership of insurance IBDs such as the purchase of AIG Broker-Dealers.

Yet with new players, that have new size and scale – and newfound access to capital, from private equity dollars to public markets capital in the case of firms like LPL – the appetite for the use of forgivable notes to attract talent has only grown. Though in practice, it’s not only the larger broker-dealers offering large note amounts up to 40% (with a few outliers that go above 40% with nine-year note periods). Midsized broker-dealers have increasingly been stepping up to the plate and offering (more modest) amounts in the 10%-15%-of-trailing-GDC forgivable note range. Though notably, regulators have been vocal regarding the potential conflicts of interest to imposing production requirements on forgivable notes, and in response, all but a handful of IBDs have made the forgivable notes based on time only.

Still, though, the practice of recruiting representatives to new broker-dealers with forgivable notes has become so ubiquitous, that many advisors have a growing sense of entitlement that if they change broker-dealer, forgivable note money needs to be part of the equation (and firms that don’t offer forgivable note money can find their recruiting efforts stunted by not offering these upfront dollars).

And as the use of forgivable notes continues to expand, so too does industry ‘innovation’ to differentiate on the value of their forgivable notes. For instance, breaking from tradition, LPL is now paying forgivable note money calculated on basis points on AUM rather than trailing-12-month GDC. Still, though, how much LPL will offer as a forgivable note is siloed, paying higher amounts on those assets that are most long-term profitable (advisory assets held in brokerage accounts that provide recurring revenue), and lesser amounts to lower profit assets such as mutual funds and variable annuities held direct at the product vendor (with less recurring revenue and/or more transactional clients). As LPL is a trend leader, the forgivable note amount based on profitability rather than production, with a skew towards recurring revenue over transactional brokers, is starting to expand to other broker-dealers as well, reflective of the overall industry shift that values recurring-revenue AUM fees at nearly twice the valuation of one-time commission-based business.

Broker-Dealer Profit Centers That (More Than) Recover The Cost Of Offering Forgivable Note Recruiting Bonuses

While the particular nature and structure of the forgivable note has continued to evolve, a function of both regulators cracking down on the more perverse conflicts of interest embodied in forgivable notes in the past (e.g., requirements to sell a certain amount of proprietary product, or potential ‘undue’ pressure to maintain or increase production), and the shifting nature of the broker-dealer model itself from commissions to fees, the fundamental approach remains the same: some broker-dealers provide upfront recruiting incentives to entice brokers to join the firm, which the broker-dealer does because it knows it can more than “make back” those upfront payments from the recruited broker and their clients over time. (As usual, there’s no such thing as a free lunch!)

In practice, the primary “profit centers” of broker-dealers today, that serve to recover the cost of providing forgivable note recruiting bonuses, include:

- Brokerage Account Transaction Charges: The “original” broker-dealer model was to generate revenue by providing brokerage services, and in a world where many independent broker-dealers are simply layered on top of a third-party custody/clearing firm, “marking up” those brokerage services are still a profit center for many broker-dealers. For example, postage and handling fees in a brokerage account costing $1 to the broker-dealer are marked up to $3 or more. Ticket charges on ETF trades cost the broker-dealer $7 – 9, but they charge the client $15 or more. Markups on systematic withdrawal and deposit charges, dollar cost averaging charges, inactive account fees, IRA custodial fees, and other nickel-and-diming fees make assets held in a brokerage account much more profitable for broker-dealers. There is a growing push for advisors to move direct mutual funds and variable annuities into a brokerage account. In turn, this means that broker-dealers miss out on a layer of profit center within brokerage accounts if products are held direct; accordingly, it is perhaps not surprising that Avantax recently notified their advisors that they will be charging the advisor $60 for every mutual fund held direct at the product company (effectively making up for some of the otherwise lost revenue).

- Revenue Sharing From Product Vendors: Broker-dealers typically negotiate with mutual funds and variable annuity vendors to receive some amount of basis points on assets gathered and/or products sold by their reps. Small broker-dealers may only make 1 - 2 bps on assets, while large broker-dealers will earn 5 - 10 basis points (bps) on both assets and sales of products (using their size for additional bargaining power). REITs and Alternative Investments earn broker-dealers between 1 - 1.5% (i.e., 100 – 150 basis points) of extra in commission on product sales, which is referred to as “marketing reallowance.” With REIT and alternative investing having taken a nosedive over the last three years, a combination of market shifts and crackdowns from regulators on inappropriate sales, the revenue stream to broker-dealers from these product lines have dropped dramatically. A concern from broker-dealers going forward is Regulation Best Interest (Reg BI) further diminishing sales of mutual funds and variable annuities (potentially dramatically), which for many broker-dealers, has been a sizable portion of their overall profits, as advisors shift to the use of ETFs (which typically have much smaller revenue-sharing agreements from product vendors).

- Markup on NTF Mutual Fund Expense Ratio: This charge is more common with large broker-dealers, where the mutual funds used in the broker-dealers No Transaction Fee (NTF) platform are an alternative higher-cost share class, with the broker-dealer participating in the added expense embedded in the NTF expense ratio, which may cost up to 30 bps or $25 per client position.

- Markups on Third-party Money Managers: Often, advisors are not aware that they pay a higher management fee on their third party money manager, because their broker-dealer adds anywhere from 5-25 basis points to the stated management fee that is shown on the platform in the first place, which the broker-dealer keeps as a profit center. An advisor we consulted with shared that he had called Schwab out of curiosity, and asked what the management fee was for the manager he used. To his surprise, the management fee at Schwab was 15 bps less. Broker-dealers often justify such charges as being ‘required’ for ongoing due diligence, but in reality, it is simply profit center (particularly when it continues indefinitely for a manager that was already vetted up front). Larger firms, and firms that pay substantial forgivable note money, are more apt to impose this cost than small and mid-sized firms.

- Proprietary Advisory Platforms: As advisors shift from brokerage to advisory accounts and from mutual funds to the use of ETFs and separately managed accounts, more and more broker-dealers have rolled out their own proprietary advisory platforms, effectively offering their own in-house managed account solutions to earn the entire management fee themselves (rather than ‘just’ the markup of a third-party money manager). In turn, some broker-dealers are increasingly using many of the same tactics that insurance companies used to drive business to their variable annuity products for the broker-dealer’s proprietary advisory platform. It is common that broker-dealers offer 100% payout on proprietary advisory platforms (because they’re earning additional fees directly), but the standard grid on all other managers, and may include further incentives to park more assets in their proprietary platforms, such as free Albridge consolidated client statements being one such perk for reaching a set threshold for assets. Notably, FINRA has thus far expressed no issue with these conflicts of interest, because such managed account solutions are not themselves products securities products like a variable annuity, they are “platforms”. Still, though, for broker-dealers with proprietary advisory platforms, it often becomes too tempting to not resort to direct and indirect tactics to drive advisor’s client’s assets into their highly profitable platforms. It is commonplace for us to receive advisor feedback that broker-dealer presidents and other management are telling advisors they really should put their advisory assets into the broker-dealer proprietary advisory platforms. And the rise of profitability on advisory accounts in the form of proprietary advisory platforms is one of the main reasons that forgivable note recruiting bonuses for advisors with a large base of existing client assets is now on the rise as well.

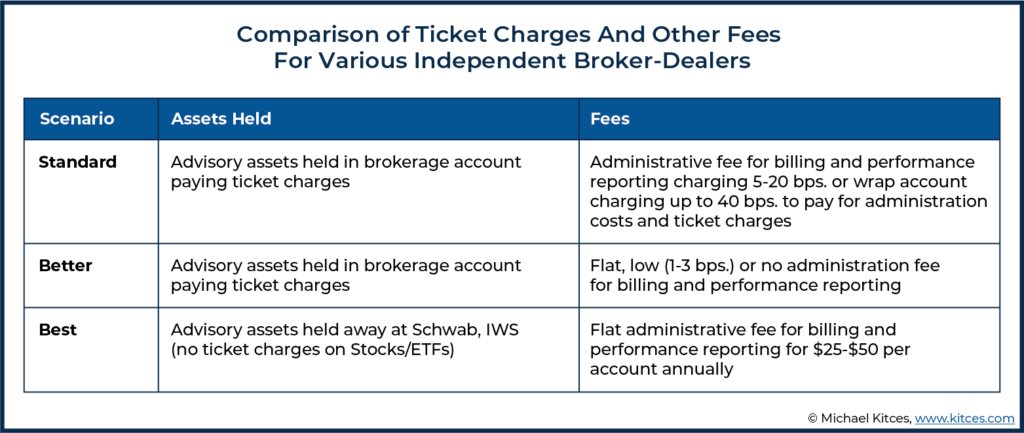

- Advisory Administrative Fee For Rep-Directed Advisory: When brokers want to manage their own advisory accounts, a growing number of broker-dealers charge an “Administrative Fee” that often runs 10 - 20 basis points. Nominally, this fee is meant to cover the costs of billing and performance reporting on behalf of advisors, but the reality is that the hard cost of such software solutions to the broker-dealer often runs little more than 2 - 3 bps; the remainder is a major profit center for broker-dealers to make up for the otherwise foregone revenue when their brokers refuse to their broker-dealer’s other profit centers (proprietary advisory platforms and revenue-sharing third-party money managers).

- Platform Fee For Holding TAMP Assets Direct At TAMP: While third-party managers selected directly through the broker-dealer’s platform are often assessed a markup, brokers who hold assets directly with a TAMP can avoid a broker-dealer’s markup; accordingly, broker-dealers often apply a “Platform Fee” for brokers that choose to hold their assets directly with the TAMP provider. Five bps is the typical cost being imposed, and like markups on third-party money managers, the rationale is that the broker-dealer is performing due diligence on the TAMP, though evening out the lower profit than if held in a brokerage account (or encouraging brokers to use potentially-even-more-profitable on-platform managers, where the markup is embedded and may feel less salient) is the motivator.

- Platform Fee For Holding Advisory Assets At Third-Party RIA Custodians (TD Ameritrade, Schwab, or Fidelity Institutional): Similar to the platform fees when brokers hold other assets direct and outside the purview of the broker-dealer’s brokerage-account-based profit centers, hybrid brokers who have an outside RIA and an external third-party RIA custodial relationship may be assessed a 10 - 20 bps “platform fee” by their broker-dealer for “administration” (billing and performance reporting), though again in practice the hard cost of such software solutions is often a fraction of this amount. In some cases, broker-dealers simply outright apply a charge for holding the assets away rather than in a brokerage account to discourage their brokers from doing so (again given that the broker-dealer’s on-platform profit centers are more often in the form of back-end markups that the broker may not see, sometimes making it appear like the external platform fee is more expensive when in reality it may or may not be).

Notably, this evolution of broker-dealer profit centers largely mirrors the evolution of the advisor business model itself over the past two decades, from what was originally getting paid for “traditional” brokerage services, and revenue-sharing agreements for facilitating the sale of securities products, into the evolution of third-party and then in-house managed accounts, and the rise of various “platform” and “administrative” fees that broker-dealers increasingly apply for their brokers (particularly hybrid brokers) that try to avoid the broker-dealer’s profit centers by holding assets away (resulting in the broker-dealer simply assessing those fees directly to the broker instead).

Of course, the reality is that broker-dealers are for-profit enterprises, and entitled to generate revenue for the services they do provide. Yet the challenge in practice is that, particularly when many broker-dealer profit centers are still less visible, or are only assessed directly to the client (e.g., in the form of markups on the solutions they receive), there is a substantive temptation for brokerage firms to incentivize brokers to join the platform (e.g., with recruiting bonuses in the form of forgivable notes), and offer higher-cost versions of their solutions to recover the recruiting bonus (and potentially earn even more on top).

How Broker-Dealers Tie Forgivable Note Recruiting Bonuses To A Broker’s Anticipated Profitability Matrix

So given these dynamics and various broker-dealer profit centers, how do broker-dealers determine how much to pay on forgivable note money?

With the amount of note money being offered increasingly based on anticipated profitability of the overall broker relationship (and less on specific production), for the profitability model, an advisor’s product mix, asset levels, where assets are held, and even compliance record are entered into a calculation matrix.

The way the matrix calculates the anticipated profitability of a broker (and therefore what the broker-dealer can offer as a recruiting bonus) varies from firm to firm. The calculation matrix will determine a number to pay in note money, with the most money awarded to advisory assets held in brokerage accounts or managed by the broker-dealer (as noted earlier, one of the broker-dealer’s largest profit centers) and lesser amounts for assets held away (on which the broker-dealer’s platform and administration fees are still relatively less profitable). In practice, some firms stick to the number determined by the matrix, while others may be willing to negotiate a higher amount in certain circumstances.

Still, how much broker-dealers pay in the form of forgivable notes is evidenced by how much they generate from different asset classes, and also by the number of profit centers they are able to impose. Those broker-dealers with a greater number of profit centers, or charging higher amounts, will be able to pay more in forgivable note money.

The Emergence Of ‘Fiduciary-Friendly’ Broker-Dealers That Eschew The Recruiting Bonus/Markup Game

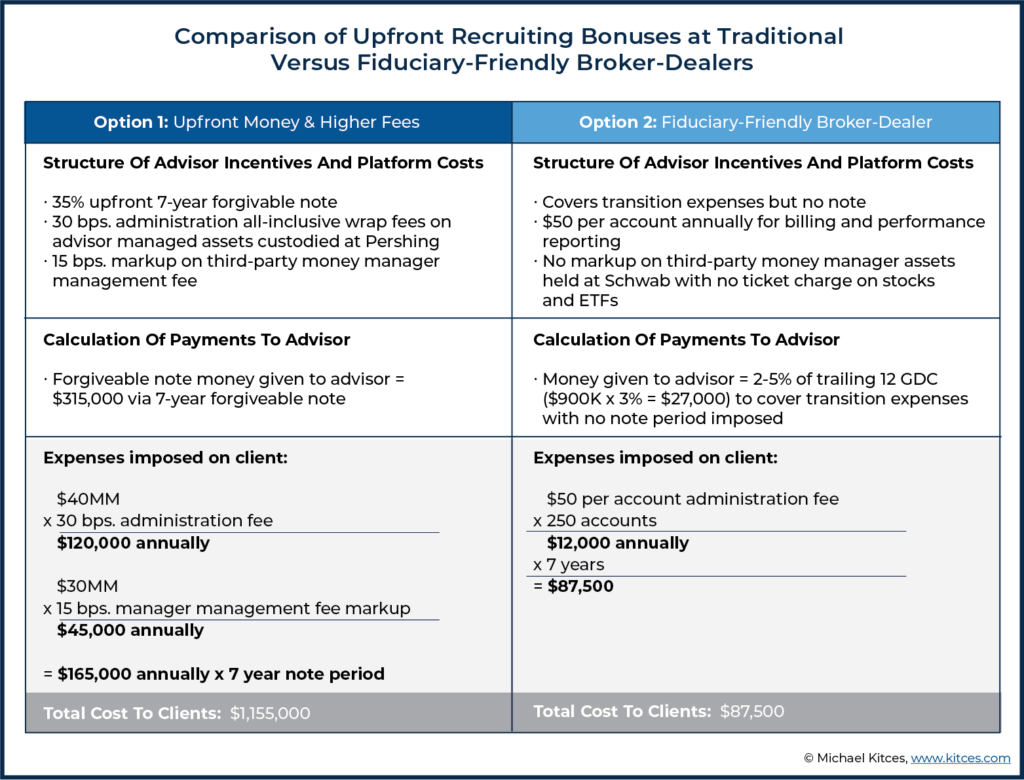

While broker-dealers can and should be able to generate revenue and earn a profit for the service they provide, the fundamental challenge of forgivable note recruiting bonuses is that they add an additional layer of cost to the broker-dealer recruiting process, that the broker-dealer can and will ultimately recover in the form of higher costs… which in turn are passed through to the client, raising the cost of the advisor’s services and potentially even making it more difficult to grow in the future (by being saddled with higher-cost providers that the broker-dealer requires that makes it difficult to charge a competitive advisory fee).

However, while some broker-dealers have gone further down the road of trying to entice switching brokers into their often-higher-cost profit centers, an alternative crop of more “fiduciary-friendly” broker-dealers have begun to emerge, which may still be involved in some product distribution revenue sharing and brokerage platform markups (the original broker-dealer model and still their core model) but do not:

- charge platform fees on assets held away

- charge markups on third-party money managers or on NTF fund expense ratios

- twist advisor’s arms to custody mutual fund assets in brokerage accounts

- have proprietary advisory platforms

- charge over 5 bps for advisor directed advisory administrative fees (numerous broker-dealers offer quality billing and performance reporting for a flat $50 per account annually to as low as zero with payout grid covering the administration fee, given that in practice these services are relatively low cost for a broker-dealer to provide at scale given modern AdvisorTech tools available today)

Broker-dealers that fit the fiduciary-friendly criteria are not applying these additional expenses… though it means they won’t have a lot of discretionary revenue for them to also offer large amounts of forgivable note money.

Here’s what they typically offer as an incentive:

- Transition expenses, which include covering the cost of ACAT transfers, registration costs, business cards and stationery, plus a small amount of additional revenue to compensate the broker for the downtime during the transition itself (e.g., 2% - 5% of trailing-12-month GDC)

- Payback loans if larger amounts are needed for expenses such as setting up a new office space (a payback loan is effectively an upfront loan to the broker in exchange for an agreement to take a lower grid payout for 2-3 years until additional note amount has been paid back). For instance, a $500k GDC advisor joins a broker-dealer and is offered a 90% payout. The advisor needs an additional $100K beyond what the broker-dealer offers in their transition package. The broker-dealer may front the advisor $100k in the form of a loan, and then put the advisor at an 80% payout for two years (instead of 90%), with the 10%-less payout paying back the $100k loan in two years ($500k production x 10% difference = $50k per year x two years = $100k repayment). At the end of two years, the payout will be raised back to 90%. Notably, if advisor production falls below $500k during the two-year payback timeline, payments will go longer than the two year period, and if production goes above 500K during the two year period, payments will be shorter than two years.

- Provide 100%-of-GDC payout for perhaps 3-6 months (saving the transitioning broker the normal grid haircut as a way to help get a little more cash flow into the broker’s firm during the otherwise-disruptive transition period)

Taking the long-term view regarding the savings achieved by avoiding the added expenses, clients come out way ahead versus the upfront money and paying the extra fees approach.

Here’s what it looks with a hypothetical but real-world example of a transitioning broker:

- $90MM total assets

- $40MM advisor managed Stocks & ETFs

- $30MM with third-party manager

- $20MM in mutual funds and variable annuities

- $900K GDC

- 250 brokerage accounts

Looking at this example, the advisor makes $288,000 more with Option 1 in upfront money. However, the client pays $1,067,500 more in Option 1 expenses over the 7-year note period. Which not only means the clients incur far more in expenses than the advisor earns in additional benefits… but the added cost layer of the broker-dealer’s markups can make it even more difficult for the advisor to compete for new clients in the years after the switch and the forgivable note, as the advisor’s investment solutions are burdened with the additional cost layers. And it may not be feasible to walk away later… or else the remainder of the forgivable note is no longer forgiven and instead comes due, requiring repayment with cash the advisor may no longer have available.

How The Collapse Of Ticket Charges And “ZeroCom” Will Further Change The Equation

The recent implementation of no ticket charges on stocks and ETFs at Schwab and IWS (Fidelity Institutional) has introduced a new competitive dynamic to the broker-dealer marketplace, as it makes holding advisory assets at popular broker-dealer clearing firms like Pershing and NFS less attractive (and makes wrap accounts obsolete).

The fiduciary-friendly broker-dealer realizes this dynamic, and that the elimination of this traditional broker-dealer profit center will, in turn, put newfound pressure on the advisory administration fee structure, so the bulk of their advisors are now transitioning to custody advisory assets away at Schwab & IWS while their broker-dealer’s fee structure is reduced to just the hard cost to provide the underlying billing and performance reporting services.

The president of a fiduciary-friendly broker-dealer shared his perspective:

“We favor the open-architecture to strategically leverage the best of brands in the marketplace. We are advocates of flexibility and choice in a conflict-free environment so our independent financial professionals can serve the best interests of their clients. Therefore, we do not mark-up or revenue share with any of our investment management service providers such as investment advisory custodians or money managers, nor do we private label such investment management service providers to create proprietary platforms.

This makes the recruiting process a little more difficult because we have to educate the advisors on how they and their clients come out ahead when some competitors may be attracting them with huge upfront bonuses or higher payouts.

It’s easy for advisors to narrowly focus on payout or upfront money when all other things appear equal. Our firm has competitive payouts and does offer upfront transition assistance, but requires us to really peel back the onion and analyze all the hidden fees at other firms. After that process is complete, it’s easier for advisors to see that they can not only make more but simultaneously reduce the fees charged to clients at other firms.

The BD, RIA, financial professional, and the client all win when they have freedom of choice to avoid proprietary platforms, high fees and having flexible options to choose based on our open-architecture environment.

Upfront forgivable notes can mesmerize an advisor as the instant gratification buttons go on steroids, given the sheer size and magnitude of some recruiting bonus checks.

A recruiting story recently shared with me reflects the power of this temptation. An advisor shared with a broker-dealer recruiter how his firm was the perfect match for his practice, but another firm that was a lesser fit was offering a big upfront check. The advisor and his wife had been looking at purchasing a beach house, and the large note would enable them to buy the property. They decided to go with the firm paying the big note. The note won, and the advisor may not have even realized how much his clients lost.

But the reality is that just as the fiduciary movement requires greater disclosures of costs to clients, an emerging fiduciary-friendly movement amongst broker-dealers is similarly bringing light to the less transparent costs that some broker-dealers add to the equation, making it feasible for advisors considering a change in platform to effectively assess the true net cost of the platform, for their business, and their clients.

Tune in to my conversation with Jon, Podcast Episode #83: Switching to the Right Independent Broker-Dealer by Understanding its Profit Centers with Jon Henschen