Executive Summary

The research on the optimal strategy to generate retirement income from a portfolio has been evolving for decades.

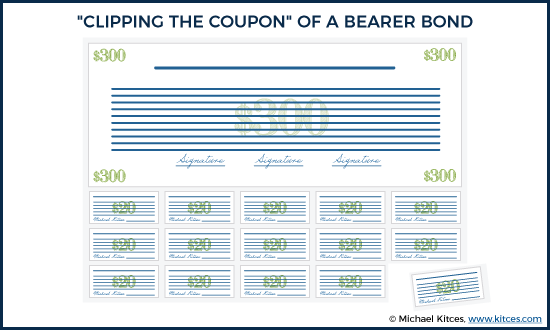

In the 1950s and 1960s, with the initial rise of a portfolio-based retirement, the leading strategy was simply to buy bonds and spend the interest (by literally “clipping the coupons” from the bearer bonds of the time). Until the inflation of the 1970s ravaged the purchasing power of bond interest.

The harsh consequences of inflation on bond portfolios led to a dramatic shift by the 1980s, as retirees increasingly purchased high-quality dividend-paying stocks instead, counting on the ability of businesses to raise prices and keep pace with inflation… which also helps their dividends to rise and keep pace with inflation as well.

The dividend strategy was popular until eventually retirees realized that owning stocks and focusing on the dividends, while ignoring the capital gains, just leads to large retirement account balances that could have been spent along the way. As a result, by the 1990s, retirement portfolio strategies shifted again, to consider a more holistic “total return” approach that incorporates interest, dividends, and capital gains as well.

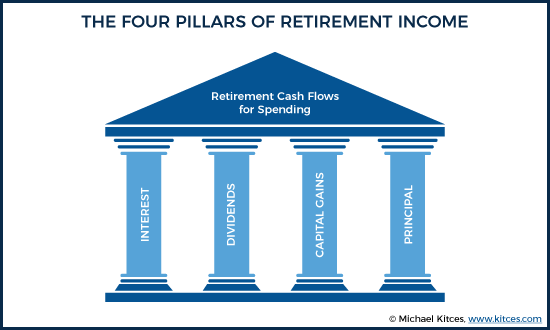

Unfortunately, though, capital gains may be one of the largest drivers of total return in the long run, but it’s also one of the least stable, forcing the retiree to periodically rely on the portfolio principal as well. Of course, in the end, retirement principal that is unspent is arguably a wasted spending opportunity – where the “optimal” retirement portfolio is for the last check to the undertaker to bounce. On the other hand, given the uncertainty of a retiree’s time horizon – not knowing when you’re going to die – means in practice, the principal can and should be used more dynamically, spending from it in some years but leaving it untouched in others.

Which means ultimately, the modern retirement portfolio will really rely on four pillars for retirement income – interest, dividends, capital gains, and principal. Or stated more accurately, the four pillars of retirement cash flows – since the treatment of the pillars as “income” for tax purposes can vary depending on both the pillar itself (interest is taxable and principal liquidations are not), and the varying types of retirement accounts (from pre-tax IRAs to tax-free Roth accounts).

Nonetheless, the fundamental point is simply to recognize that a retirement portfolio has multiple ways to generate the desired cash flows for retirement. And in fact, in a low yield environment, it can be especially important to diversify across all four pillars – or retirees take on additional risks in stretching for yield, from interest rate and default risk (from longer-term or lower-quality bonds), to the concentration risks of buying just a subset of the highest dividend-paying sectors (which, as the financial crisis showed, can expose the portfolio to severe risk along the way!).

Buy The Bonds, Spend The Coupons

In the early days of bond investing, bonds were issued as “bearer certificates” (or “bearer bonds”), which literally meant that whoever was bearing (i.e., holding) the bond was presumed to be its owner (akin to how cash works today).

In turn, this meant the interest payments that bond issuers would pay to bond owners was paid directly to whoever actually held the bond – redeemed by a paper coupon, attached to the bond, that could be physically cut from the bond and presented for payment. Thus why a bond’s interest rate is often called its coupon rate, and why collecting the interest payments from a bond is still often colloquially called “clipping the coupon”. (Because in the past, that’s literally how it was done.)

With the rise of the ‘modern’ investing and retirement era after World War II, the strategy of “buying bonds and clipping the coupons” was the leading approach for retirement income from a portfolio, either in lieu of a pension or Social Security (for those who didn’t have one or weren’t eligible), or to supplement it. The stable coupon payments were an effective substitute for stable pension payments, and were increasingly appealing through the late 1950s and into the 1960s as interest rates drifted higher with economic growth.

And of course, for those who needed a little more money as well, they could always sell the bonds (or wait for them to mature) for some additional cash flow. In the context of pension funds and institutions that needed to support a large volume of ongoing payments, it was common to “ladder” the maturities of the bonds sequentially, specifically to ensure that the principal value of a maturing bond would be available to supplement cash flows that year. Though for individuals, the liquidation of the bonds themselves was often more ad hoc, given the uncertainty of the retirement time horizon in the first place.

Inflation Triggers A Shift To Dividend-Paying Stocks

One of the key challenges of the “clip the coupons” bond strategy for retirement income is that bonds – particularly the ones issued in decade past – simply paid a “nominal” coupon rate that was always the same, regardless of inflation. Which meant that over time, inflation could and did erode the purchasing power of the bond income. Fortunately, though, inflation rates were modest in the 1950s and 1960s. And most people didn’t necessarily plan to live for decades in retirement, which further limited any material long-term danger from inflation.

Then the 1970s struck, and an inflation rate that had averaged only 2.0% in the 1950s and 2.3% in the 1960s jumped to 6.2% in 1973 and then spiked to 11.0% in 1974, severely damaging the purchasing power of bonds purchased in the preceding decades. In fact, from 1973 to 1982 the average annual growth rate of inflation was a whopping 8.7%, which cumulatively cut the purchasing power of bond interest by 57% in a decade. And at the same time, a growing realization was underway that with improving health, “retirement” can actually last a very long time (where the cumulative impact of inflation really matters!).

As a result, by the early 1980s, the focus of retirement income planning portfolios had shifted from buying bonds and clipping the coupons, to buying stocks and spending the dividends, instead. The bad news about dividends is that the yields weren’t as high – in 1982, the S&P 500 dividend yield was about 5%, while the 10-year Treasury was 12.5%. The good news, however, was that the rising price of goods (from inflation) was lifting up the earnings of the businesses that sold them; of course, the businesses would have to pay employees more in a rising inflationary environment as well, but the net result was still a significant increase in nominal profits.

For instance, if a company used to generate $1,000,000 of revenue with $800,000 of expenses and the remaining $200,000 paid out in dividends, and inflation caused prices to double, then revenue would rise to $2,000,000, expenses would jump to $1,600,000, and the business would pay out $400,000 in dividends. The end result: the business profit margins remain the same, but inflation doubling prices causes the dividends to double along with it, allowing the dividend investor to maintain purchasing power.

And throughout the 1980s, this is exactly what happened. In 1981, the S&P 500 paid out approximately $7 of dividends (when the index was at $133, for a 5.3% yield), and by 1990 it was paying out about $12.5 (when the index was up to $340, for a 3.7% yield). The end result was that the yield actually fell, as stock prices rose, but the retirement spender saw their retirement cash flows rise almost 80% (from $7 to $12.5), easily keeping up with the inflation rates of the decade (which averaged 4.7%, or a cumulative increase of “just” 58%).

Of course, the caveat of the dividend-paying stock strategy for retirement income was that dividends are not guaranteed, and in fact, the stocks themselves have economic risk. Which meant dividend-paying strategies of the day typically focused on the highest quality “blue chip” stocks, that were most likely to stick around and continue to raise their dividend payouts over time.

The Bull Market Stokes Appreciation For Capital Gains

By the 1990s, the leading retirement income strategies began to shift again.

The “challenge” was that while dividends were in fact growing at a more-than-ample rate to keep pace with inflation, the underlying value of the stocks were growing as well, quite significantly. As noted above, not only did dividend payouts rise 80% through the 1980s, but the raw price level of the S&P 500 was up 150% as well. In other words, the retiree’s account balance by the end of the decade was more than 2.5 times the account balance at the beginning of the decade, even after spending all those dividends along the way.

This recognition that it’s necessary to consider the impact of stock growth and capital gains reformed the thinking on retirement income portfolios once again. The shift was on to view portfolios more holistically, considering the availability of interest, and dividends, and capital gains, and spending on the basis of the “total return” portfolio. And the impact was substantial, given the sheer magnitude of the capital appreciation potential. Personal finance publications of the day routinely suggested that 7% to 8% withdrawal rates would be ‘reasonable’ and sustainable, given total return expectations for markets at the time.

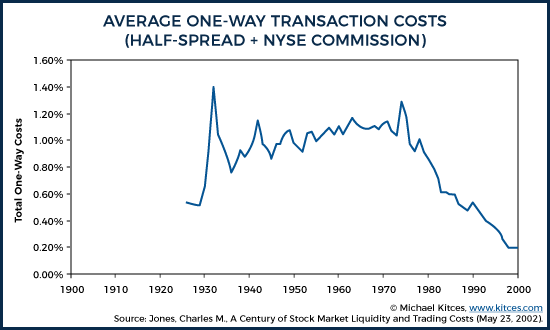

Notably, the inclusion of capital gains as a pillar of retirement income portfolios was also aided greatly by the decline in investment transaction costs since stock trading commissions had been de-regulated on “May Day” of 1975. In the subsequent 20 years, the average cost to complete a stock transaction had fallen by about 90%, which made accessing capital gains (via a sale) “almost” as liquid as just receiving dividend or interest payments.

Spending Principal, But Not Too Soon

In the early years of a portfolio-based retirement, it was often used as a supplement to a defined contribution pension plan or Social Security (or other income-producing assets like real estate). However, with the decline of the defined benefit plan and the meteoric rise of the defined contribution plan throughout the 1980s and 1990s, the use of a retirement portfolio shifted from being supplemental to the core of funding retirement itself. Which introduced a new challenge to thinking about retirement planning: what to do with the retirement account balance itself.

In a world of defined benefit pension plans, there was no account balance. The retiree received payments for his/her life, or payments for the joint survivorship of the retiree and his/her spouse, and at death, the payments simply stopped. With a defined contribution plan, though, there was an account balance, which if not fully used, would remain available for heirs.

In some cases, the potential to leave a “legacy” of the remaining retirement account balance was simply a gift to bestow upon family members or charitable entities. But in many cases, the fundamental goal of the retiree was to “use the money” in retirement – which meant not only the growth on the retirement account, but the principal, too. From this perspective, the retirement account was something to be spent and maximally consumed; a remaining balance at the end meant wasted opportunities of how the money could have been spent during life. The perfect retirement plan was one where the last check was for the undertaker, and it would bounce.

Of course, the challenge to this approach is that retirees don’t necessarily know how long they’ll live. Which means planning to bounce the undertaker’s check was risky, as if the retiree spent the principal down too soon, and then “failed to die in a timely manner”, all the money would be gone. Thus, the use of retirement principal became another part of the balancing act – spending down too soon would lead to disaster, but not spending down at all was a “waste”, too.

Coordinating The Four Pillars Of Retirement Cash Flows

Ultimately, these components of interest, dividends, capital gains, and principal form the four pillars of retirement income planning. And as noted earlier, ever-declining transaction costs made it comparable to spend interest and dividends, or reinvest them and liquidate capital gains from some other investment instead, or keep it all invested and spend from principal… in other words, the four pillars of retirement income became increasingly fungible and interchangeable, to be shifted amongst from year to year as necessary to fund the retirement goal.

In fact, liquidations from the modern retirement portfolio will likely shift amongst all four pillars from year to year and decade to decade. In some years, the biggest drivers to total return are from interest and dividends, which can be taken and spent. In other years, a bull market means ample capital gains that can be liquidated for retirement spending instead, especially in times of low yields from interest and dividends. In “bad” years, it may be preferable to tap principal, in order to leave the rest of the portfolio invested for a hopeful future rebound. In fact, diversification across the four pillars of retirement income can be a highly effective way to protect against the potential stressors that can adversely impact a retirement plan.

Notably, it’s crucial to recognize that not all retirement “income” is actually taxable income. In fact, the process to optimize the tax-efficient liquidation of retirement accounts is entirely separate, including determining when to tap taxable vs pre-tax (IRA) vs tax-free (Roth) accounts, proper asset location of available investment assets across the different types of retirement accounts, as well as ongoing tax-efficiency strategies like the timing of harvesting capital gains and losses and engaging in systematic partial Roth conversions.

In fact, arguably when thinking about a retirement portfolio, it’s better to think in terms of “retirement cash flows” than retirement income, as what constitutes “income” for investment purposes (interest and dividends, but not principal) is different than what constitutes “income” for tax purposes (as interest and dividends might be tax-free coming from a Roth, while principal may be fully taxable if withdrawn from a pre-tax retirement account).

In other words, while it’s necessary to consider (and possible to optimize) the tax treatment of income, ultimately the purpose of the retirement portfolio is to generate the cash flows on a total return basis to satisfy the retiree’s spending needs, regardless of whether the Internal Revenue Code calls it “principal”, “income”, “taxable”, or “tax-free”.

Risks Of The Traditional “Income” Approach

Notwithstanding the shift in thinking and research about retirement income from portfolios over the years, it’s notable that a material segment of retirement investors still focus on a “traditional” income-based approach to retirement, with a focus on investing for interest and dividends.

As noted earlier, the first challenge of this approach is that it completely ignores the other two pillar of capital gains and principal. While some might simply argue that leaving the principal untouched and letting capital gains be a bonus is simple conservatism, the sheer magnitude of their potential introduces a risk that the retiree drastically underspends relative to the lifestyle that the portfolio could afford. As is, even a total return approach already leaves a high likelihood of not touching principal until the last decade of retirement.

However, the situation is clearly further complicated in today’s environment due to the low absolute level of yields, including both dividend yields and bond interest rates. In turn, this can lead retirees to “stretch for yield”, which typically entails an increase in risk, as bond investors must either buy longer-term bonds (increasing interest-rate risk) or lower quality bonds (increasing default risk) to get more yield. Similarly, stock investors looking for better yields by focusing on the highest-dividend-paying stocks typically end up concentrating the portfolio into narrow sectors, which introduces new risks as well; after all, financials were the highest dividend-paying sector of the mid-2000s (right up until they weren’t, when the financial crisis unfolded in 2008!), and in today’s environment, the top-paying dividend sectors also include utilities and basic materials (energy), both of which are now attracting warnings as valuations move to historically dangerous levels. In the meantime, as investors have stretched for yield in bonds and dividend-paying stocks, the S&P 500 is up over 200% from the market bottom in 2009.

But again, that’s actually the whole point of relying on (all) four pillars of retirement income. You don’t necessarily know which one will produce the desired results from year to year, but diversification gives you the best shot to get it from somewhere, without taking on excessive risk or portfolio concentration in stretching for yield along the way.

So what do you think? Do modern retirement portfolios rely on four pillars of retirement income? Is it important to diversity across all four pillars? Are there risks to the "traditional" income-based approach to retirement? Please share your thoughts in the comments below!

Inclusion of an income annuity (NOT an equity index annuity) but a low cost immediate annuity solution can take a lot of risk out of one’s portfolio and help with Longevity Risk. It was not mentioned here and should have been. Certainly, there is an inflation risk with a fixed stream of payments, but in many cases the guaranteed income stream benefits outweigh the inflation risk, especially during market swoons.

At the beginning Michael mentions that the focus is on income generated ‘by a portfolio’. I think he was purposely focused on that alone, not SS, not annuities, tontines, pensions, etc.

I agree 100%. If you are fortunate and have a large enough portfolio to meet all your spending needs and desires, then you don’t have to deplete it as you near death.

A pure income approach will focus only on dividends and the income risk that the dividends will not be grown or that they may be reduced. The price of the security along the way is not a factor. This is the substantive difference between a total return vs. pure income approach. The benefit of ‘ignore the price’ is primarily psychological to the retiree, but that does not mean the perceived benefit is not real.

This is my 16th year of managing our retirement portfolio only for income. 5 of the 51 income stocks (all financials) I was holding in 2008/2009 cut their dividends, leading to about a 7% decline in income that fully recovered in 5 quarters due to organic portfolio income growth. Income risk is real and must be managed through income diversification.

The pure income approach requires careful planning if it is to work through market declines, and this is planning unique to this form of investing. Those not willing to do so should not attempt it.

For retired households with ‘normal’ levels of Social Security and Pension income(s), there will be room in the 15% bracket to take full advantage of qualified dividends taxed, at least under current law, at 0%.

Unrealized capital gains in a taxable account are indeed an issue for those who have been employing this strategy. Portfolio value, although not part of a pure income strategy, will become dominated by dividend growth stocks that have been the most successful in dividend growth over the years. The ideal outcome would be a full step up in basis at death to beneficiaries, assuming such estate rules continue as they are. The risk in sitting on such long term gains is that companies are bought out, merged or go private and we get all that gain in one year. One long term solution to such a condition is the gradual annual sell/immediate repurchase of such appreciated shares.

So what to do with all of this appreciated valuation in later years of retirement? That’s a good question. One strategy might be to sell and spend down. Another might be to begin a charitable gifting plan of the most highly appreciated stock. Another plan might be to use such appreciation in value as a source of self-insuring long term care. Its always preferential to problem-solve the affliction of excess.

For a deeper dive into the principal moving parts of the pure income approach, take a look at my book ‘Retirement Investing for Income Only: How to Invest for Reliable Income in Retirement Only from Dividends’

Once again another very limiting discussion by advisors that don’t have the access to or the understanding to evaluate the risk/reward of using truly self-directed IRAs to allow retirees access to investing directly into secured real estate investments that have higher yields than stocks and bonds. By avoiding investing in real estate and private equity people miss out on the majority of investments that are even in their own communities. FYI, anyone thinking they have an allocation to real estate in a REIT just either added stock market volatility and high fees to their portfolio

Sounds like a grinding axe in search of a whetstone. I don’t see anywhere that Mike specifies what assets are in the IRAs. You can read most of this blog post with a self-directed IRA in mind.

I only see a reference to stock dividends and bonds, no direct reference to any asset classes like real estate, I may have missed that reference point but just pointing out that most advisors do not incorporate private equity, commercial real estate, private notes etc into a portfolio. I do not have a series 7, just a 66 so I am under the assumption that many firms do not allow directly holding or selling private placements due to internal compliance and regulatory issues. Forgive me if I misread the article

Michael,

I like your graphical depiction of a bearer bond. It brought back memories of client’s calling because they lost the coupon’s. Thankfully, they no longer issue bearer bonds and most outstanding ones have matured.

This evolution of retirement income is something I have been speaking to clients and others about for years. As usual, you did a nice job of encapsulating it. Your article can serve as a good reference piece for all advisors serving the pre-retirement and current retirement client.

Your point about the presence of a large segment of retirement investors who still focus on the “traditional” income-based approach is very evident in the discussions I have with people, especially new clients.

Great piece. Not explicitly mentioned is the notion that if an investor is going to maintain an asset allocation – for example 60% equities/40% bonds – in a rising equity period stocks will be sold for rebalancing purposes but also, as a byproduct, generating cash for current and future spending.

is 2 million enough in this day and age to retire on?

I’m having more trouble with this particular model than most of your excellent essays. It’s about what is included or excluded, and how you divide it up. (As an engineer I always relate models back to underlying time and space, and look for “eigenvectors” of components that span the space with minimum overlap.)

In my mind, in retirement you start with your actual/estimated spending needs, then deduct what I call “perennial income streams”: Rent, royalties, pensions (including SS), annuities, interest, dividends. What’s left, if you have a shortfall (and of course the amount varies over time depending on many factors that change both spending and returns) must come from liquidating principal.

And of course even my “pillars” are somewhat fuzzy in several ways… You can make buy/sell decisions to create/delete various income streams; pensions, SS, and annuities have some overlaps; etc.

Your pillar model focuses on interest and dividends, and then mixes them with capital gains (only accessible by some liquidation) and principal (presumably the original cost basis?)

Alan,

To put it in your terms – this was only intended to discuss the portfolio vector in particular. Not the others (Social Security, immediate annuitization, etc.).

Though yes, it’s worth noting that the potential for the portfolio to be switching over to other vectors (e.g., annuitizing assets) is a crossover I didn’t discuss here. Thought the article was long enough already? 🙂

– Michael