Executive Summary

From October 1st through October 3rd, the Academy of Financial Services’ annual meeting was in Nashville, TN – partially overlapping with the FPA’s BE Annual Conference. The event brought together many academics and practitioners to share and discuss research, with the intention of increasing academic-practitioner engagement by holding two of the largest conferences for both researchers and practitioners in conjunction.

In this guest post, Derek Tharp – our Research Associate at Kitces.com, and a Ph.D. candidate in the financial planning program at Kansas State University – provides a recap of the 2017 Academy of Financial Services Annual Meeting, and highlights a few particularly studies with practical takeaways for financial planners.

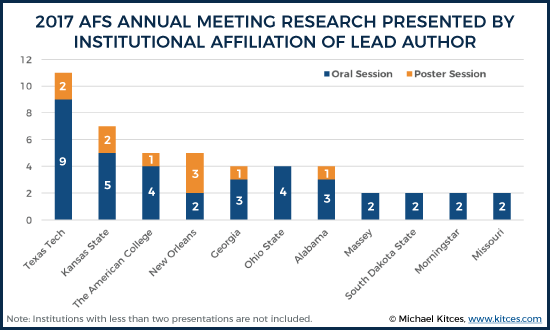

The 2017 Academy of Financial Services (AFS) Annual Meeting showcased research from scholars at a wide range of institutions – with first author affiliation on paper and poster sessions representing roughly 40 institutions. As expected, the core financial planning programs had a strong presence, with scholars from just seven of those institutions serving as lead authors for more than 50% of all research presentations and poster sessions.

The AFS annual meeting featured research on a number of different topics. Some notable sessions for practitioners ranged from topics such as whether having resources from friends and family reduces a household's willingness to establish an emergency fund (not as much as you might expect!), how bull and bear markets impact the subjective assessments of portfolio risk, the links between certain types of personality traits and likelihood of financial stress, and quantifying the financial advisor's value when it comes to making efficient investment decisions (and how that value varies depending on the investor's existing capabilities in the first place).

Overall, holding the AFS Annual Conference and FPA BE Conference in conjunction appeared to be successful in creating greater engagement between practitioners and researchers (with some research presentations filling large rooms at standing room only capacity!). As both the AFS Annual Conference and CFP Board's Academic Research Colloquium strive to create more robust platforms for sharing and engaging in academic research, the future appears bright for financial planning researchers (and research that can really be used by financial planning practitioners)!

2017 Academy of Financial Services Annual Meeting

Though perhaps lesser known among many financial planning practitioners, the Academy of Financial Services has a long history of promoting academic research within the area of financial services. Dating back to 1985, the AFS has aimed to promote interaction between practitioners and academics. One way the AFS pursues this objective is by publishing an academic journal, the Financial Services Review (FSR). In recent years, AFS began to publish FSR in collaboration with the Financial Planning Association, and as a result, FPA members receive digital access to the current volume/issue of the journal.

Another way the AFS encourages interaction between practitioners and academics is through holding their annual meeting. This objective was given even greater focus in 2017 as the AFS held its Annual Meeting in conjunction with the FPA BE Annual Conference, conducted as a “pre-conference” event of its own but with one day of overlap to the main FPA conference agenda (which allows practitioners to come early and participate in the AFS event, and for academic researchers to stay beyond the AFS meeting and participate in the FPA annual conference as well).

Academic Representation At The 2017 AFS Annual Meeting

The 2017 AFS Annual Meeting drew researchers from a number of academic and professional institutions. In total, roughly 40 institutions were represented as first authors on research presented in either poster or oral sessions.

For those who haven’t attended an academic conference before, academics generally present their research at conferences in one of two ways. The first is the poster session, which is a more informal presentation where a researcher stands in front of a large poster summarizing their findings. The second are oral sessions, where researchers deliver a more formal research presentation to an audience. Researchers must submit their sessions in advance for consideration to be selected for presentation.

Several of the well-known financial planning programs had a strong showing at the 2017 AFS Annual Meeting. Texas Tech led the way with scholars serving as first author on 9 oral session and 2 poster sessions. Kansas State ranked second with scholars serving as first author on 5 oral sessions and 2 poster sessions. Other schools with a strong presence included The American College, University of New Orleans, University of Georgia, Ohio State University, and the University of Alabama. In total, these 7 schools accounted for 54% of the first authors of research selected for oral or poster sessions.

2017 AFS Annual Meeting Research With Practical Applications

Notably, a core mission of AFS is “to encourage basic and applied research in the area of personal financial planning”, which means that not all of the research presented at an academic conference like the AFS Annual Meeting will be research that is directly applicable within a financial planner’s firm.

Basic research—i.e., research conducted irrespective of practical applications—is an important element of science that is needed to help move fields forward. As such, some studies will naturally seem impractical to practitioners. Nonetheless, the 2017 AFS Annual Meeting did include many studies with practical takeaways for financial advisors.

The Value Of A Gamma-Efficient Portfolio

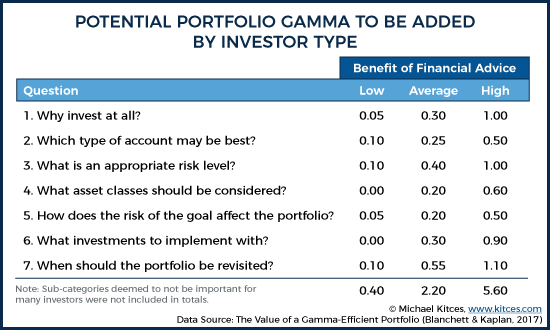

Building upon their prior study of the value financial planning can add (i.e., “gamma”), David Blanchett and Paul Kaplan, both of Morningstar, take a narrower look at gamma solely from the perspective of implementing a gamma-efficient portfolio strategy.

In their paper, The Value of a Gamma-Efficient Portfolio, Blanchett and Kaplan examine this question from the perspective of three hypothetical investors who receive varying levels of benefit (low, average, and high) from with working with an advisor, acknowledging that some people (e.g., those without the knowledge or desire to manage their own portfolio) receive more value from professional portfolio management than others (who may be comfortable with and capable of self-managing).

Specifically, they utilize a seven-question framework to evaluate the portfolio construction process:

- Why invest at all?

- Which type of account may be best?

- What is an appropriate level of risk?

- Which asset classes should be considered?

- How does the risk of the goal affect how I invest?

- What investments to implement with?

- When should the portfolio be revisited?

The authors provided a detailed analysis of the potential gamma to be added related to each investment question.

As is indicated in the chart above, Blanchett and Kaplan conclude that different levels of financial advisor value are experienced by different types of investors. And of course, different levels of value are delivered by different types of advisors, as not all financial advisors are going to fully deliver gamma in each category.

Specifically, their results suggest that when consumers receive average or high levels of benefit from working with a financial advisor (and when the advisor can actually deliver the value), the gamma that can be added from efficient investment strategy selection is significant enough to justify a typical AUM fee. However, when consumers receive low levels of benefit from working with an advisor (e.g., because they are already capable of self-implementing a long-term diversified portfolio), it may be hard to justify a typical AUM fee based on investment gamma alone.

And while this insight may seem somewhat self-evident, Blanchett and Kaplan provide some concrete estimates of the value that may actually be received by various types of consumers. Further, evaluating the different categories can help advisors see where they can generally add the most relative value. For instance, while asset class selection is important, helping clients to decide to save and invest in the first place is relatively more important for each type of consumer.

Blanchett and Kaplan’s study is a big step forward in terms of addressing the “compared to what” problem and many of the limitations of prior studies attempting to quantify the value of advice. By providing a framework that spans multiple dimensions of potential value-add, their quantification of value becomes much more meaningful. If a particular investor is “low” on questions 1-3, “average” on 4-6, and “low” on 7, a customized value-add unique to their circumstances can be calculated. While it may not be perfect, the benchmark in this study is beginning to look much more like a real person.

Example 1. John is a consumer who has a very good understanding of the importance of investing, appropriate risk levels, asset allocation considerations, and how the risk of his retirement goal affects a portfolio allocation, but he only has an average knowledge of what types of accounts to use, what investments to implement with, and when he should revisit his portfolio. Therefore, assuming John’s prospective financial advisor is of high competence in all areas, John’s benefit of working with an advisor (or developing the skills and knowledge on his own) could be estimated as 1.4% per year.

Of course, this study doesn’t even attempt to quantify the value of financial planning gamma (meaning the true potential value-add would be even higher), but Blanchett and Kaplan have provided a solid foundation for beginning to more precisely quantify the value-add of an efficient portfolio.

Fragile Families’ Challenges For Emergency Fund Preparedness

While the importance of maintaining an emergency fund is no secret amongst financial planners, understanding the relationships between household characteristics and emergency fund preparedness can help financial planners identify situations in which extra precaution should be taken to ensure client households are prepared to face financial adversity.

Unmarried parents with children—i.e., “fragile families”—are one group that is particularly at risk of needing to rely on an emergency fund. Because non-married households are more prone to breaking apart than married households—a process which can create a shock to income while simultaneously increasing expenses (e.g., needing to make two rent/mortgage payments instead of one)—an emergency fund is even more important for fragile families.

As Elizabeth Warren and Amelia Warren Tyagi have noted in their book, The Two-Income Trap, these dynamics are not unique to low-income households. In fact, in some respects, fragility can be even higher for young, affluent, dual-income households, as an unexpected drop in income may result in larger month-to-month deficits with fewer options to offset that decline (e.g., public support or a non-working spouse entering the labor force).

In an effort to examine emergency fund preparedness among fragile families, Abed Rabbani, an Assistant Professor at the University of Missouri, and Zheying Yao, a Ph.D. student at the University of Missouri, analyzed data from the Fragile Families and Child Wellbeing Study.

In an SSRN article, Rabbani and Yao report their findings. While not all of their findings are particularly surprising—e.g., higher income, saving behavior, and homeownership were all found to increase the likelihood of having an emergency fund (defined as two months’ income in savings)—the authors also examined whether the likelihood of having an emergency fund was impacted by the gender of the individual who controls household spending, or whether the family could obtain financial support from other friends or family members.

The authors expected that financial reliance would be negatively associated with having an emergency fund (as having an emergency fund may be less crucial when households can access resources elsewhere) and that households where a female has financial control would be more likely to have emergency funds. However, the authors found that neither exhibited a statistically significant relationship with the likelihood of having an emergency fund after controlling for factors such as debt, saving, income, employment, and homeownership.

In a practical context, this study can provide a few different insights—particularly for advisors who may specialize in working with younger, non-traditional families. First, some objective factors that we would expect to be correlated with the likelihood of having an emergency fund were found to be. While this finding isn’t groundbreaking, it is good to check that professional intuitions align with empirical findings. Second, the findings suggest that neither gender of the financial decision maker, nor the availability of family/friend financial support, were significant predictors of the likelihood of having an emergency fund.

In the case of the latter, this may suggest that merely having access to funds through friends and family does not sufficiently disincentivize creating an emergency fund for one’s own household. This is actually an encouraging finding, as it may suggest that households are looking to be self-sufficient even when other friends-and-family resources may be available as a last resort. This may be particularly relevant for financial planners given that our clientele—even in the case of non-traditional clientele served through retainers and other business models—does tend to be more affluent, and likely has more affluent social networks as well. Additionally, this finding may lessen the concern of parents that serving as a financial backstop could undermine their children’s willingness to develop their own emergency funds and fiscal responsibility.

Do Investors' Subjective Risk Perceptions Influence Their Portfolio Choice? A Household Bargaining Perspective

Misalignment between perceived and actual risk is a genuine threat to sticking with a financial plan, as it means that even if a client does have the “right” portfolio consistent with their risk tolerance, if they misperceive the risk of their own portfolio, they may try to make inappropriate portfolio changes anyway.

Xianwu Zhang, a Ph.D. student at Texas Tech University, explores whether subjective risk perceptions influence portfolio choices, in his paper, Do Investors’ Subjective Risk Perceptions Influence Their Portfolio Choices? A Household Bargaining Perspective.

In general, Zhang finds that investors perceive the stock market to be riskier than objective measures suggest it is. However, what is particularly interesting about Zhang’s research is his examination of the role that household bargaining plays in portfolio selection.

Traditional models of households assumed that all members of a household act as a team—altruistically putting the interests of the family ahead of their own. However, household bargaining models acknowledge various individuals within a group have different preferences, and, as a result, conflicts of interest arise within the household. Thus, households can act either cooperatively or competitively as individual members seek to maximize their own satisfaction.

When analyzing the different ways in which families can act cooperatively or competitively, bargaining power is an important concept to acknowledge. In the context of household portfolio selection, disproportionate bargaining power can mean that one spouse dominates decision making.

Zhang utilizes several proxies of bargaining power—such as gender, education, income, and hours worked—to see how risk perceptions (measured as perceived likelihood that a mutual fund invested in blue-chip stocks would experience a 20% decline over the next 12-months) of a spouse with more bargaining power may influence the percentage of risky assets in a household’s portfolio. Utilizing data from the HRS, Zhang finds that, all else equal, the subjective risk assessments of females, spouses with more education, and spouses with lower income have a greater influence on risky asset investment.

One interesting aspect of Zhang’s findings is that it is not always the household member who is assumed to have more bargaining power whose subjective risk assessment seems to influence portfolio holdings. For instance, spouses with more income are assumed to have greater bargaining power, though Zhang finds it is those with less income whose subjective risk perceptions have a greater influence on portfolio allocation. Zhang notes that this may be because the higher earning spouses may have higher opportunity costs, and thus delegate this decision making to a lower earning spouse.

Zhang does note some important limitations to this study (e.g., it is only based on one point in time rather than evaluating behavior over time), but it is certainly a fascinating and important topic.

From a practical perspective, these findings reiterate the importance of engaging both spouses in the financial planning process. And this is particularly true in light of our industry’s historical neglect of the female members of households, as even if it is the case that a higher-earning male possesses more bargaining power within a particular household, it may actually be the lower-income female’s risk assessment which is driving portfolio risky asset investment decisions of the household!

Further, this type of analysis raises all sorts of important questions. How do couples delegate portfolio decision making between themselves? How do they delegate portfolio decision making when an advisor is involved? If an advisor is struggling to get buy-in from a couple, who should they try and influence and how should they do so? It's unlikely that any of these questions have simple answers, but they are the types of research questions that fiduciary advisors who want to help their clients fulfill their goals must consider.

The Effect of Advanced Age and Equity Values on Risk Preferences

In another paper examining risk preferences, David Blanchett of Morningstar, Michael Finke of The American College, and Michael Guillemette of Texas Tech University examine the effect of advanced age and equity values on risk preferences.

Utilizing a unique data set of risk tolerance questionnaire (RTQ) responses from participants in a defined contribution managed account solution offered by Morningstar Associates, the researchers are able to analyze how RTQ responses from January 2006 to October 2012 were associated with age and equity values after controlling for other factors such as account balance, annual salary, and savings rate.

The researchers find that as the S&P 500 increases, workers become less risk averse, and vice-versa. Additionally, participants who were older, had lower income, and had lower account balances were found to have higher levels of risk aversion.

Blanchett et al. note that the higher levels of risk aversion among older participants provides justification beyond time-horizon considerations for reducing equity allocations with age. Further, these findings suggest that annuitization should be more common than it is, though the authors note that several factors may decrease the attractiveness of annuitization, including mortality salience and framing effects.

The authors also note that an interaction found between age and S&P 500 levels suggests that risk preference assessment of older individuals may be influenced by stock market valuations. Specifically, if risk preferences were assessed when market values are high, respondents exhibited more desire to take on risk. But, of course, investing more in stocks because they’re up only makes investors more at risk of losing money in the next bear market! Fortunately, target date funds and other strategies can take the rebalancing responsibility out of the investors hands, which may help shield the investor form losses due to changes in shifting risk preferences.

From a practical perspective, financial planners should consider that risk tolerance assessment should not just be a one-time occurrence. A growing body of research suggests that investors exhibit time-varying risk aversion. Of course, this too raises questions.

If risk aversion is not stable, then how should it be used in practice? Does behavior change as stated risk preferences change, or are people were changing the way they answer questions related to risk preference (perhaps driven by risk perception instead)? Does a one-dimensional measure of risk aversion even tell us much in the first place? And to what extent should retirement strategies be designed differently if there’s an anticipation up front that retiree risk tolerance will decline in their later years?

Multidimensional Financial Stress: Scale Development and Relationship with Personality Traits

As financial planners shift from simply thinking about the quantitative aspects of financial planning to helping clients achieve more holistic financial health, understanding measures of financial stress and well-being will be increasingly important.

In their presentation, Multidimensional Financial Stress: Scale Development and Relationship with Personality Traits, Wookjae Heo of South Dakota State University, Soo Hyun Cho of California State University Long Beach, and Phil Seok Lee of South Dakota State University, presented their work in developing a multidimensional measure of financial stress.

In an SSRN paper covering a similar topic, the researchers provide a glimpse into some of the topics which are important in developing a more comprehensive measure of financial stress. The authors note that there are affective (i.e., how people feel), psychological (i.e., cognitive and behavioral), and physiological (i.e., bodily responses) dimensions to stress. As a result, they aim to bring these different dimensions together into a single scale that can be used to assess financial stress.

Further, the researchers used this measure in a survey of 1,162 respondents to examine its potential use and possible relationships between Big Five personality traits and financial stress. Those who exhibited the highest level of financial stress were moderately extraverted, were low in agreeableness, low in conscientiousness, high in neuroticism, and high in openness. Conversely, those who exhibited the lowest levels of financial stress were highly extraverted, highly agreeable, highly conscientious, low in neuroticism, and highly open to experience.

From a practical perspective, gaining a better understanding of what types of clients are more or less likely to experience higher levels of stress can help advisors manage client comfort and look out for various behavioral tendencies. Research in this area still has a long way to go before advisors can use such findings with confidence, but this is one area where the importance of basic research is highlighted—even if the immediate applications are limited. If we don’t even truly understand what financial stress is, we will struggle to effectively help our clients alleviate it (or identify the clients most prone to financial stress in the first place)!

Overall, the 2017 AFS Annual Meeting was successful in bringing together a wide range of scholars to share their research in personal financial planning. And hosting the conference in conjunction with FPA BE provided an excellent opportunity to increase the interaction between practitioners and academics as well.

The AFS Annual Meeting will be held in conjunction with the FPA Annual Conference in 2018—again providing an opportunity for greater engagement between financial planners and researchers. So, if you would like to stay on top of some of the latest ideas in academic research, would like to consider possibly getting involved in research yourself, or simply just want to experience an academic conference first hand, attending the AFS Annual Meeting and FPA Annual Conference in 2018 may be a convenient opportunity to do so!

So what do you think? Did you attend the 2017 AFS Annual Meeting? Do you have plans to attend in the future? What else can be done to help further engagement between practitioners and academics? Please share your thoughts in the comments below!

Leave a Reply