Executive Summary

Whether it is a free sample in the grocery store (where the store hopes the sample convinces the shopper to purchase the item), or ‘Freemium’ software (where the developer hopes that consumers using a more basic version of their software will lead them to purchase an enhanced version), consumers are used to being offered free goods as part a company’s marketing process. But offering free financial plans remains controversial in the financial advisory community. Even if some prospects could become clients as a result of receiving the free plan, some advisors ask, might offering plans for free reduce the perceived value of financial planning in consumers’ minds?

A research study conducted by Kitces.com Lead Researcher Derek Tharp suggests that offering an initial financial plan for free doesn’t reduce the value of the plan in consumers’ minds. Furthermore, not only may it be the case that free financial plans don’t diminish the perceived value of financial plan, but offering paid one-time plans at typical fees charged by advisors could actually decrease the perceived value of ongoing planning relative to offering free initial plans! In an experimental study, participants were given a scenario in which they received a $1 million windfall inheritance and were seeking out an advisor to help them manage it. The participants were divided into four treatment groups based on the cost of their initial financial plan: either free, $1,000, $2,000, or $3,000. They were told that the advisor’s planning strategies would save them more than $500,000 in taxes during the next 30 years, and were then asked what they thought a reasonable annual fee would be to pay for ongoing services from the advisor.

While some observers might expect that participants in the experiment who were told the initial plan was free would pay less for ongoing services, those who were told they would receive a free plan suggested the highest price of all treatment groups! One possible explanation for this effect is that the price of the initial standalone plan set expectations for the participants of the value of ongoing services. In the case of the experiment, those who were assigned a non-free price for the initial plans perhaps used their respective prices as ‘anchors’ when estimating the value of ongoing planning, using those prices as reference points when considering what ongoing fees would be reasonable, whereas those who were to be given the free plan did not have any such reference points to work from (and perhaps were compelled to focus more on other details, such as the given amount of projected tax savings).

Ultimately, the key point is that goods or services that are ‘free’ are not necessarily perceived as having lesser value; on the contrary, research suggests that clients might be more willing to accept higher annual fees if they are provided with a free initial plan rather than one with a price significantly less than the advisor’s ongoing fees. Which means that advisors may want to consider either increasing their fees for initial plans (raising client expectations of the cost of ongoing planning), or using a model with a free initial plan that helps the client better understand the value of the advisor’s services and, at the same time, avoids an ‘anchor’ price that weighs down their expectations of the advisor’s fees!

It is commonly argued that offering ‘free’ financial plans upfront can diminish the value of financial planning services. The general reasoning given is that if a professional is doing something for free, surely that must mean it is not worth much. By contrast, paid financial plans – by virtue of actually having a significant dollar value assigned to them – are presumed to be perceived as more valuable.

However, this need not always be the case. In fact, there are all sorts of goods and services given away for free that aren’t presumed to be worthless. For instance, free software trials, a free initial medical or legal consultation, or even the blog post you are reading right now.

It turns out that ‘free’ is actually one of the more interesting prices that exists. Unlike the difference between most dollar values on a continuum (e.g., $107 versus $108), the reality is that 'free' is not just another point on a spectrum, but rather a categorically different price itself.

For instance, in a 2007 study in Marketing Science, researchers Kristina Shampanier, Nina Mazar, and Dan Ariely set up an experiment selling chocolates on campus to students at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. The researchers presented students with an option to buy a low-value chocolate (Hershey’s) or a high-value chocolate (Lindt truffle), and then varied the price over three conditions:

- Cost condition (“1 & 15”): The Lindt cost $0.15 and the Hershey’s cost $0.01;

- Free condition (“0 & 14”): The Lindt cost $0.14 and the Hershey’s cost $0.00; and

- Alternate free condition (“0 & 10”): The Lindt cost $0.10 and the Hershey’s cost $0.00.

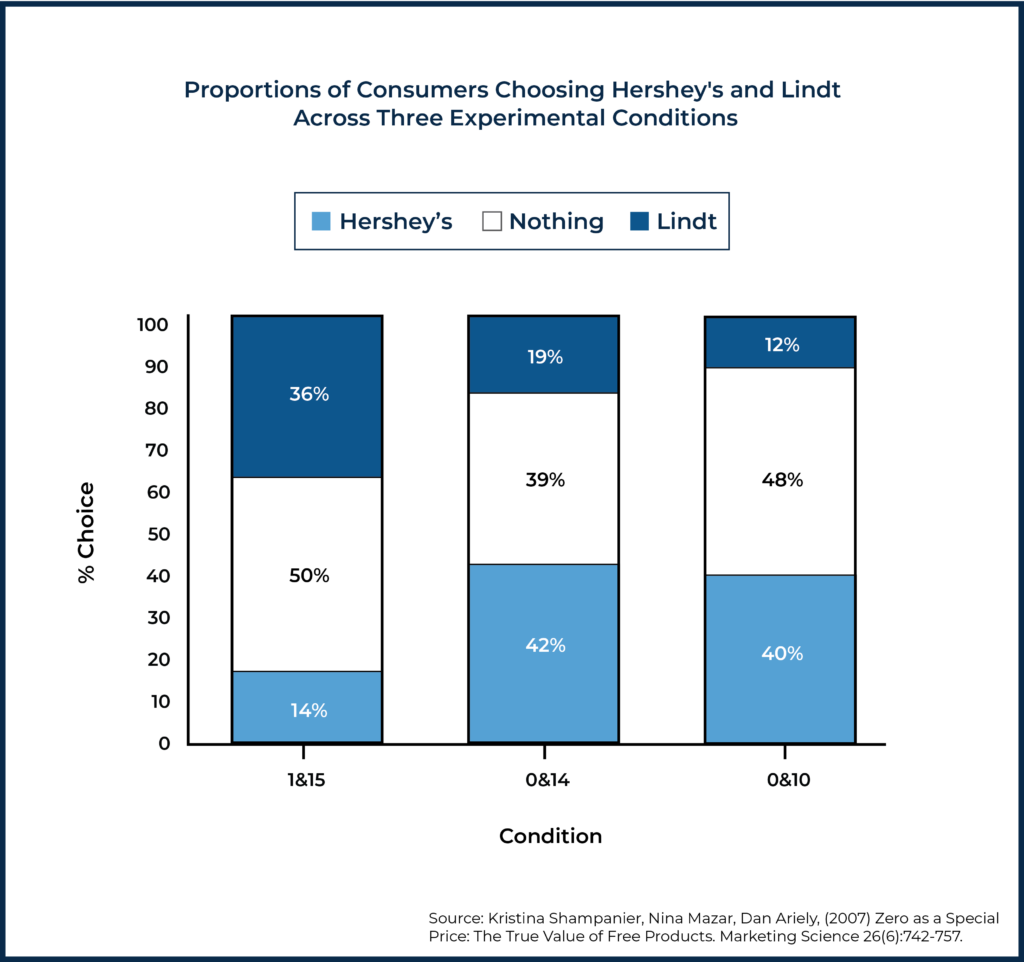

The results of the study are shown visually below.

Notably, between the cost condition (“1 & 15”) and the free condition (“0 & 14”) the price difference between the two chocolates was a constant $0.14. In other words, the Lindt was consistently priced $0.14 more than the Hershey’s between these two scenarios. And yet, when the price was decreased by a mere $0.01, the behavior of participants in the study changed dramatically.

Under the 1 & 15 cost condition, requiring students to pay at least $0.01 for the Hershey’s chocolate, 14% of students chose the Hershey’s, 50% chose nothing, and 36% chose the Lindt. But as the 0 & 14 free condition shows, once the Hershey’s was offered for free, then 42% chose Hershey’s (versus 14% previously when it was $0.01), 39% chose nothing (versus 50% previously when there was no free option), and 19% chose the Lindt (versus 36% previously, even though the Lindt was now $0.01 lower than before).

Interestingly, in the 0 & 10 alternate free condition, reducing the price of the Lindt to $0.10 actually further reduced the proportion of students who chose the Lindt, with a sizeable increase in the 48% of students who opted for nothing (versus 39% previously) between the scenarios with the free Hershey’s offered.

The key point here is that the proportion of students opting for the free Hershey’s in the 0 & 14 condition (42%) tripled versus the students choosing the $0.01 Hershey’s in the 1& 15 condition (14%) despite the price difference between the Hershey’s and the Lindt remaining constant, which would seem to be a violation of a standard cost-benefit perspective.

The authors interpret the students’ behavior as an illustration of our psychological tendency to overreact to free prices, where we put too much weight on the value of something that is free versus something with a very low price – just as the authors suggest people may do when they spend hours waiting in line for a free Starbucks drink.

In his book, Predictably Irrational, Dan Ariely (coauthor of the study mentioned earlier) explores how the initial prices offered can have an anchoring effect on perceptions of value. In one study, Ariely handed out two different questionnaires to his students in class under the guise of trying to figure out how much he should charge to read poetry. Half of the class was first asked if they would pay $10, while the other half was first asked if they would be willing to be paid $10 to listen to him. After that, everyone was asked how much they felt the price should be to hear him read short, medium, and long versions of his poetry, without specifying whether that price was to pay to hear the poetry or to be paid to listen.

In his book, Predictably Irrational, Dan Ariely (coauthor of the study mentioned earlier) explores how the initial prices offered can have an anchoring effect on perceptions of value. In one study, Ariely handed out two different questionnaires to his students in class under the guise of trying to figure out how much he should charge to read poetry. Half of the class was first asked if they would pay $10, while the other half was first asked if they would be willing to be paid $10 to listen to him. After that, everyone was asked how much they felt the price should be to hear him read short, medium, and long versions of his poetry, without specifying whether that price was to pay to hear the poetry or to be paid to listen.

Students who were first shown the price of $10 (i.e., asked if they would pay this much to hear the poetry reading) offered to pay somewhere between $1 (short) and $3 (long) to hear him read a poem. By contrast, students who were first shown the price of -$10 (i.e., asked if they would take payment to hear the poetry reading) requested to be paid somewhere between $1.30 (short) to $4.80 (long) to listen to his poetry.

In his book, Free: The Future of a Radical Price, Chris Anderson explains that an anchor “…calibrates a consumer’s sense of what a fair price is. It can have a dramatic effect on what they’ll ultimately pay.” Which is precisely what the students in Ariely’s study illustrate.

In his book, Free: The Future of a Radical Price, Chris Anderson explains that an anchor “…calibrates a consumer’s sense of what a fair price is. It can have a dramatic effect on what they’ll ultimately pay.” Which is precisely what the students in Ariely’s study illustrate.

To be clear, this was the exact same professor asking both groups of students the exact same question: “What should the price be to hear me read short, medium, and long versions of my poetry?” The only difference was that those who were first asked how much they would pay (i.e., saw the positive price) tended to place a positive value on his readings while those who were first asked how much they would need to be paid (i.e., saw the negative price) tended to place a negative value on his readings.

In other words, the first price offered anchored the participants' perception of the value, and that carried through to whether they reported if they would be willing to pay or need to be paid for the service.

Anchoring And Price Perceptions In Financial Planning

Of course, financial planning is very different from a good such as chocolate or a service such as a poetry reading. Similar to how the evidence of loss aversion – that losses loom larger than gains – varies quite significantly by context, with some who argue that this shouldn’t even be treated as a generalizable finding, it’s certainly possible that the pricing of financial planning services could follow entirely different relationships.

To explore this question, I conducted a study examining how the price of an initial plan offered influenced the perception of the value of ongoing financial planning services.

For the study, 602 individuals were recruited to participate in an online survey. Participants were told that they just received a $1 million inheritance and, because they are unsure how to manage it, they would meet with a financial advisor who prepares an initial financial plan for them. Each participant was randomly assigned to one of four treatments: a $1,000 initial plan, a $2,000 initial plan, a $3,000 initial plan, or a free initial plan. After specifying the cost of the initial plan put together for them and some description of the potential long-term tax benefits of the strategies identified, participants were then asked how much they thought a reasonable fee would be for ongoing financial planning services.

Specifically, participants were shown the following prompt:

Imagine that you’ve just inherited $1,000,000. The money came as a surprise and you are unsure how to best manage it.

You meet with a financial advisor who prepares a financial plan for you [as part of a free initial consultation/at a cost of $1,000/at a cost of $2,000/at a cost of $3,000].

In addition to a strategy for growing your funds at a reasonable rate of return into the future, the financial plan also included a detailed tax planning strategy illustrating how you could reduce your tax burden by over $500,000 over the next 30 years.

If you were to hire this financial advisor to assist you with managing your inheritance on an ongoing basis, what do you think a reasonable annual fee would be for their services?

Notably, the tax planning element was intended to provide a more tangible estimate of at least a portion of the long-term value that individuals might receive from ongoing financial planning services, and, in each case, participants were told that the plan identified a strategy for reducing one’s tax burden by over $500,000 over the next 30 years.

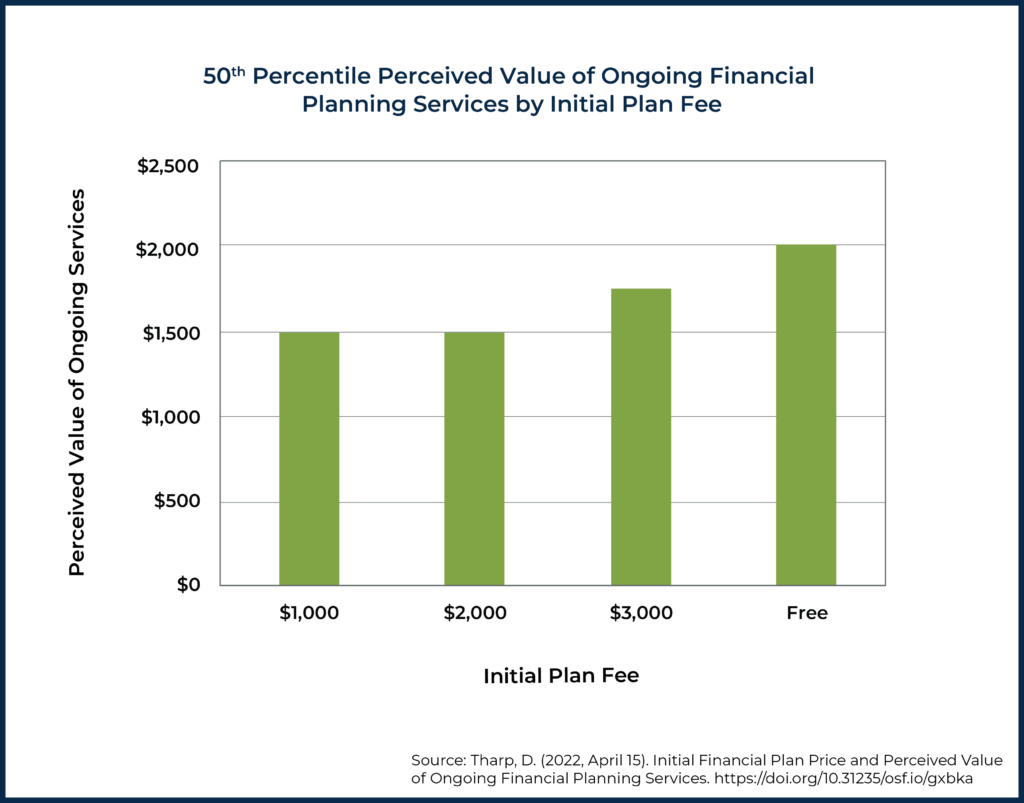

At the median, individuals who had $1,000 and $2,000 initial plans valued ongoing services at a level of $1,500, whereas the value perceived by individuals with the $3,000 plan was $1,750, and those with free plans had the highest perception of all at $2,000!

Notably, at the median, these levels are still far below what advisors would typically charge for ongoing financial planning services, regardless of the plan presented. Recall that the individuals were told they inherited a $1 million portfolio. Previous Kitces Research has found that advisors currently charge right at 1.0% for a $1 million portfolio at the 50th percentile level. So even the free plan with the highest perceived value was still perceived as valuable at a price about 5x less than what advisors are currently charging in the real world.

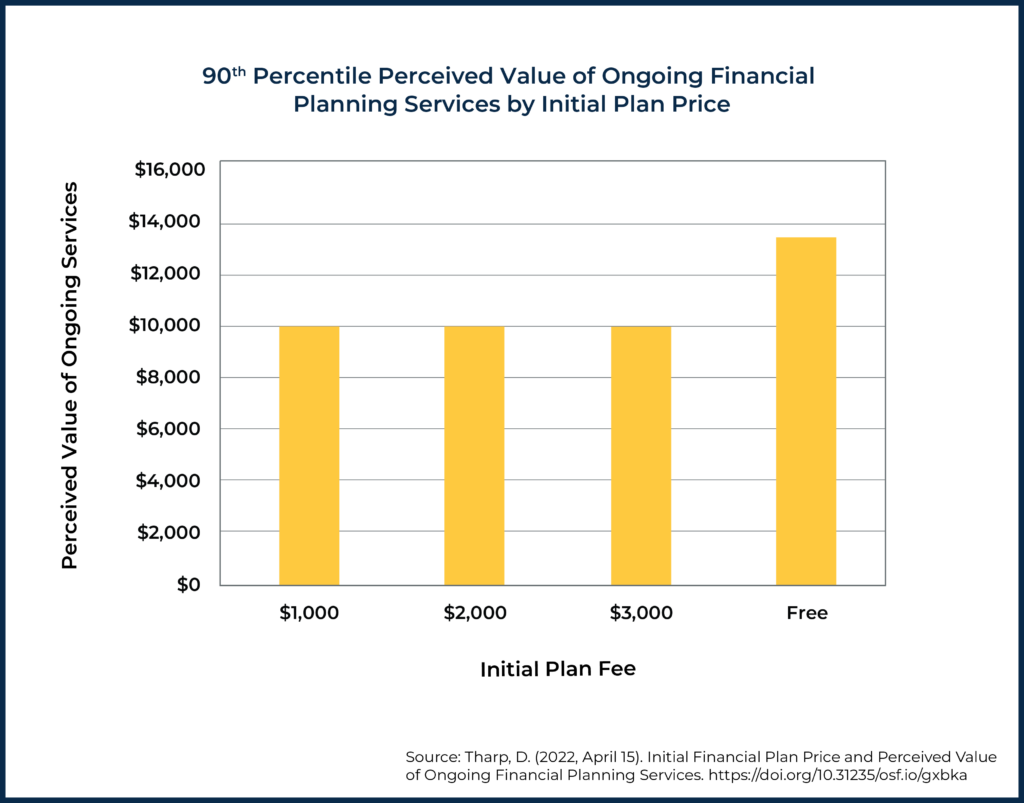

So what about at higher percentiles of perceived value? Do we see the same relationships there? Yes, we do!

Among all paid plans at the 90th percentile of perceived value, the value is fairly consistent right at the $10,000 level – which is right on par with the 1.0% typically charged within the industry. However, the free initial plan is the only plan value that exceeded this value at a 90th percentile perceived value of $13,500 – or roughly 1.35%. Interestingly, this is very close to the 1.3% reportedly charged by 90th percentile advisors at the $1 million portfolio level in our previous Kitces Research studies.

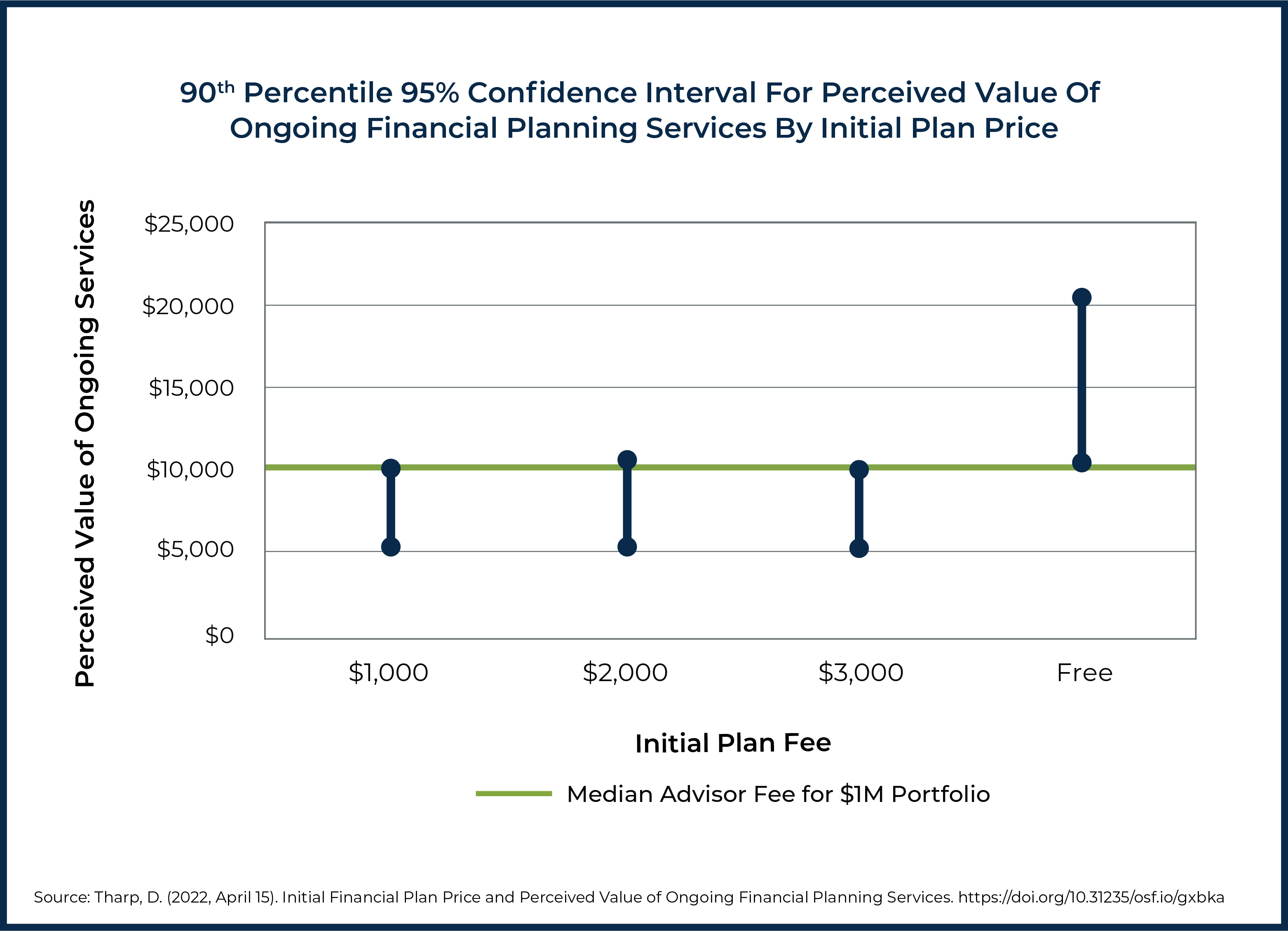

If we estimate the 95% confidence interval for the perceived 90th percentile value of ongoing financial planning services, we find that it ranges from about $5,000 to $10,000 (or 0.5% to 1.0%) for each of the paid plan scenarios (though, technically, the $2,000 initial plan scenario ranged from $5,000 to $11,000), but the free initial plan ranged from $10,000 to $20,800 (or 1.0% to 2.1%).

Or, to put it all more concisely, the perceived value of the paid plans tested was somewhere between a heavily discounted fee and median fee levels within the industry, whereas the free plan was perceived to be valuable at a level somewhere between the median fee level and a premium fee within the industry.

What Could Cause These Disparate Perceptions Of Free Financial Planning?

So why could this be? Why wouldn’t it be the case that the free plan is thought of as the least valuable, whereas the paid plans are perceived as more valuable?

One potential explanation is that the typical initial standalone plan prices (not including the free plan, which is a special case) – which are all far below market rates for annual ongoing services despite being roughly in line, albeit possibly a little low (i.e., $1,000 at 10th percentile and $3,000 at 75th percentile, based on recent Kitces Research) for standalone financial plans – actually pull down the perception of ongoing services.

After all, if an advisor is willing to put together a client’s initial plan for $3,000, then why should the client pay $10,000 (or more) for ongoing services, when they could just come back again next year and ask for another ‘one-time’ plan for $3,000? Offering the initial plan at $3,000 makes it seem like perhaps that is a reasonable estimate of what annual ongoing pricing for those services could be, which can tempt clients to think that they may be able to save money by opting for a series of one-time plans strung together, versus signing up for actual ongoing services.

However, the price itself may have little bearing on what the true value of a professional’s services is. When presented with the free initial plan, individuals in the study did not have the same price to use as a cue for estimating value (compared to the other individuals in the study who were given dollar amounts for their initial plan), and instead needed to rely on other details shared – such as the $500,000 of tax savings projected over the next 30 years. Notably, these same tax savings were present in every scenario presented to all respondents, but it appears that offering services at a non-zero price may weigh a bit heavier and have an anchoring effect on consumer perceptions of indicators of value.

But what about the notion that someone might just be able to come back and get services for free every year? Isn’t that a concern?

Well, not really. Unlike putting together a standalone plan for $3,000 – which one might interpret as a reasonable rate for a future plan – we’re all aware that a professional service provided at no cost is not an offer for repeated services at no cost. Rather, we’re likely to interpret such an offer as more of a demo, trial, or possibly even a sales pitch. In fact, one of the downsides of offering a free initial plan could be that it may increase skepticism and reduce trust. If the client is sitting through a free plan presentation wondering when the “Gotcha” will come and what’s in it for the advisor, then they may not be engaged the same way.

Of course, avoiding skepticism and maintaining trust aren’t necessarily difficult to accomplish, and can be achieved by demonstrating through one’s actions that a plan is meant to educate and is not (at least purely) a sales pitch.

The key point here is simply that typical costs for standalone plans are much lower than typical costs for ongoing services and that consumers may mistakenly confuse the two as equivalents for one another. After all, it doesn’t seem that unreasonable to ask an advisor who charges $3,000 for an initial standalone plan why a consumer couldn’t just buy that plan once per year rather than pay an ongoing $10,000 per year fee.

Of course, that overlooks all of the many additional benefits that can come with truly ongoing planning and asset management. Asking for a standalone plan once per year is not necessarily as equivalent to receiving ongoing services as one might think, but we can at least understand why an initial price like $3,000 could pull down the perception of the value of ongoing financial planning services.

“But No Other Professionals Work For Free!”

Another common argument against free initial plans is that no other professionals work for free. However, we can find numerous examples across other areas of medicine, finance, law, engineering, and related professional fields where some significant investment is put into an initial pitch, demo, or consultation before rendering paid services.

For instance, consider cosmetic surgery. Some cosmetic surgeons charge for consultations and some don't, but there's often a fair amount of planning work that goes into a consult. Evaluating a patient, determining their goals, coming up with a strategy, and presenting that strategy (possibly including visualizations and other ‘work’ to help the patient understand the plan and potential outcome).

In many ways, an initial financial plan may be a lot like a 3D visualization of a nose job. Very different in obvious ways, of course, but in both cases, the ‘work’ done is simply making the future outcomes of working with a professional more tangible. It's certainly not the most valuable aspect of the work, though. If someone wants their nose (or financial situation) to look different in the future, it is going to take some further work to make that happen. The real value of rhinoplasty (or financial planning) comes from getting stuff done, and nothing actually gets done during a free consultation.

The debate on charging for initial consultation versus not charging is not unique to the financial advisory industry. Going back to the cosmetic surgery example, the American Board of Cosmetic Surgery has an overview on their blog that covers the pros and cons of charging for initial consultations – specifically noting that “not charging a consultation fee does not mean that a surgeon is desperate for patients or less reputable.” Rather, reasons given for not charging for an initial consultation include the professional’s confidence that those who see their process will want to move forward, eliminating the fee as a barrier keeping prospective patients from learning more, encouraging patients to get more consultations (which may be cost-prohibitive if each was paid), and to reduce pressure to go forward with services because of a fee (particularly when the fee is refundable if the patient moves forward with a provider).

The point here is not that arguments don’t exist on the other side of the debate – certainly, they do – but rather that the concept of free initial consultations is not at all unique to financial planning. Moreover, we also see free services offered in areas of law (e.g., free malpractice suit evaluation), engineering (e.g., bidding for a project/design when there’s no guarantee it will be selected), finance (e.g., an investment banking pitch), and many other fields.

Kicking The Tires – The Value of Free Plans In Financial Planning

One of the most valuable aspects of a free financial plan is that it helps a client learn more about a financial advisor and how they operate. So much of financial planning is intangible and highly abstract. If asked to describe their services, advisors tend to sound very similar (e.g., “We are fiduciaries who put your interests ahead of our own, provide comprehensive financial planning, etc.”).

Financial planning is a ‘credence good’ meaning that it is hard to ascertain its value even after receiving such services. Unfortunately, this is largely because one would need to have some expertise themselves to really assess the quality of a professional’s technical aspects of financial planning.

Instead, consumers may tend to key in on other factors, such as how responsive the advisor is, how well they connect with them, how trustworthy they seem, and whether the advisor came referred from a trusted third-party. While it may still be hard for consumers to assess quality even after 10 years of working with an advisor, a free initial plan can at least provide some perspective that a consumer might have trouble credibly obtaining otherwise. Moreover, the general practice of offering free plans helps consumers shop around when they may be unwilling to invest in hiring multiple advisors for initial plans.

The initial plan also becomes an opportunity for advisors to educate prospective clients about the value of financial planning more generally. Most advisors have probably had the experience of opening a client’s eyes to a planning opportunity that the client didn’t even know was possible and wasn’t on their radar. Whether it is Vanguard’s Advisor Alpha, Morningstar’s Gamma, Envestnet’s Capital Sigma, or other estimates of advisor value, studies have consistently found considerable value, such as Vanguard’s measure of Advisor Alpha, which estimates that advisors using their framework can potentially add approximately 3% annually in net returns when averaged over long periods of time.

Yet many of the ways that advisors do add value (e.g., asset location, retirement withdrawal sequencing, behavioral coaching) may not be in areas where most consumers even realize there’s value to add. Therefore, education is crucial to help prospective clients better understand the value of working with an advisor in the first place, as some prospective clients new to hiring a financial advisor may naturally be hesitant about spending several thousand dollars on a one-time plan or the prospect of paying thousands of dollars per year in annual fees.

For example, if an advisor can show a prospective client how strategic Roth conversions in retirement could end up saving the client $500,000 in after-tax wealth without taking any additional risk, suddenly the prospect of paying $10,000 per year (or more!) in annual fees may seem more reasonable to the prospective client – particularly when considering all of the other benefits that they may receive from working with an advisor. The key point here is that a prospective client who may be initially unwilling to pay for one-time or ongoing services may become willing to pay once they understand the value that an advisor can provide.

Can Advisors Charge More For One-Time Plans?

One reaction to the plan pricing study above may be that advisors should actually be charging more for one-time plans, which is an interesting hypothesis that the study could have addressed more directly.

One considerable challenge to this, however, is that ongoing planning is, itself, truly more valuable than anything that a one-time initial plan can offer. A single change by Congress could entirely upend even the best-laid plans. Moreover, half of the battle is staying on top of and identifying when such changes occur. Professionals who are deeply engaged within a niche and see similar clients going through the same processes hundreds of times simply gain a perspective and some insight that is difficult for a DIY investor to maintain.

Nonetheless, it is worth at least considering what standalone plans with prices that are comparable to (or more than) the cost of a single year’s worth of services provided by an ongoing plan could look like. Even though it may be a very tough sell – particularly when so many other competitors are delivering free financial plans – there is probably some room for really niched advisors to reach that pricing level.

And, of course, the discrepancy between the pricing of the one-time plan and ongoing services goes away once the advisor charges more for an initial plan. For instance, if an advisor charges $15,000 for a one-time plan for a client with $1 million or $10,000 per year for ongoing services (a discount model that is similar to retailers providing a discount when someone subscribes to the ongoing delivery of a good), then the effects observed in this study could be different (and possibly even reversed) when one-time fees are equal to (or greater than) the cost of standalone plans.

Ultimately, the 'Freemium' model is a well-established and valid business model. It works particularly well when there are cross-subsidies involved, such as how a free financial plan could be used to sell financial products (historically) or ongoing financial planning services (more recently).

The key point, however, is that ‘free’ is not necessarily associated with perceptions of lesser value. Moreover, the presentation of a price for initial plans that are not free can serve as an anchor point or cue for generating a certain perception of value for future services based on that initial price, which can mean that the (typically) lower prices charged for one-time plans could actually be diminishing the perceived values of ongoing financial planning services!