Executive Summary

Developing good habits, like eating healthy, exercising, and saving for a rainy day, is a challenge that we all share. Clients of financial advisors are no exception, as no matter how carefully advisors craft financial plans and formulate sensible strategies to help clients achieve their goals, the majority of those clients struggle with following through on their tasks, even though they are 100% on board with the strategies they’ve agreed to adopt!

Future self-continuity, i.e., the ability to relate to one’s ‘future self’, is one factor that may explain why some clients struggle with plans they know, on a practical level, make sense to follow, but still have difficulty following through on the tasks they need to carry out. Research in the area of future self-continuity (FSC) – which examines three general areas: relatability, vividness, and positivity – suggests that increasing future-self continuity (i.e., improving one’s ability to relate to their future self) can increase financial self-efficacy, leading to a higher likelihood that clients will follow their financial plans and carry out the tasks outlined in their plans.

The first area of FSC research, which examines relatability, asks how a person’s perception of their ‘current self’ compares to their vision of their future self, with respect to goals, values, and priorities. This is important because the more a person considers their future self a completely different person (versus an older version of themselves) the less likely they will be inclined to act on something today to benefit their future self. For example, someone who identifies their future self as a stranger may have a difficult time committing to saving for retirement on a regular basis, even though they may understand intellectually that it is for their own benefit. The second area of research, vividness, asks how clearly a person is able to envision their future self, factoring in physical and circumstantial changes. For example, a client who has recently divorced (or whose spouse has died) that is able to clearly envision a version of their future, without their past partner, may have an easier transition recovering from what can be a devastatingly difficult situation. And the third area of research, examining positivity, asks about the level of esteem one has for their future self and how important is it for the future self to be happy and successful. Which is essential for achieving goals in a financial plan, because the more a client feels their future self is worth planning for, the more likely it is that they will follow their plan.

Ultimately, the key point is that FSC is a useful (and simple!) tool that advisors can use to help clients better relate to their future selves, which can make it easier for them to follow the strategies implemented in their financial plan, as it’s the future self who will reap the rewards of their goals. Assessing FSC can also be useful for advisors to gauge any psychological gaps that may exist for a client between their current and future selves. Not only can advisors use these concepts to determine whether to check in with their clients more or less frequently (as clients who are less attuned to their future selves may benefit from more frequent reminders of why sticking to their plan remains important in the long run), but it can also help the advisor identify the underlying reasons why their client may find it challenging to stick to their plan in the first place.

The fact that Americans just don’t save enough to successfully meet retirement and other financial goals has been a long-standing challenge, and is once again becoming a hot topic – a recent survey found that 21% of working Americans don’t save anything at all, and another 20% save 5% or less of their annual income for retirement, emergencies, and other goals. But while the propensity to save for financial goals can be bolstered by a person’s income level and how motivated they are to actually achieve their goals, there are other factors that can strongly influence a client’s motivation to save.

Future Self-Continuity: A New Solution To An Old Problem And How It Works

Future self-continuity (FSC) is the connection and perceived association between who you are today and who you will be in the future. The idea and theory of future self-continuity were developed out of research focused on understanding and curing the problem of future discounting, which is the human tendency to place less importance on future rewards when compared to current rewards. And because of this tendency, it can become very easy to put off (or even ignore) behaviors associated with future rewards, from simple ‘bird in the hand’ scenarios (e.g., taking $50 today instead of $60 next week), or (not) saving and investing for retirement. As such, FSC researchers have been exploring ways that might encourage people to develop habits now, in support of achieving future rewards, versus relying on actions much later in the future, that inevitably become more urgent and potentially more difficult. And the interesting or fun thing about FSC research is that it’s primarily conducted using innovative face-aging technology and avatars!

Despite the fact that FSC research is conducted using some fun and novel methodologies, the issues examined focus on some important and provocative topics of particular interest to financial advisors, and fall into three general areas.

The first area of FSC research relevant to advisors examines how similar a person’s perception of their current self is to what they envision as their future self. Will the future self have the same likes, dislikes, goals, values as the current self? This is important for the financial advisor who expects to maintain long-term relationships with clients, because over time, as goals and values change, a client’s financial planning needs will adjust accordingly. The second area examines the vividness of future self. This deals with the ability to actually see one’s face aged over time, and/or how vivid a future scenario is envisioned, such as imagining what being in retirement might be like. And the third area of research looks at the level of positivity one has for their future self. Do you care about your future self, and/or do you think your future self will be better, happier or sadder than your current self? For example, do you see retirement as a good thing or a scary thing?

What may be most important about this field of research to financial advisors, though, is that increasing future self-continuity can potentially enhance financial self-efficacy. Clients, through a future self-continuity practice or process, may actually engage in their financial plans and carry out their financial tasks at a higher rate. Moreover, by helping clients develop FSC skills, we may be contributing to the development of strong financial self-efficacy which goes further than our other answers to common financial planning problems like getting clients to save more or complete estate planning paperwork, not to mention setting up the opportunity to create a more client-centric financial planning process. Like risk literacy (i.e., the ability to make good decisions by understanding and internalizing risk probability) and other programs designed to improve a client’s overall financial efficacy, FSC provides another example of how to engage with clients on a very personal level to help them develop proactive behaviors with respect to their own financial lives without necessarily putting them on auto-pilot (e.g., using pre-commitment schemes), telling them what to do (which we know does not work), or teaching them (which only seems to work some of the time).

How Future Self-Continuity Manifests (And Why FSC Matters) In Financial Planning

High self-continuity (feeling highly connected to the future self) has been linked to better health, wealth, and ethical behavior. Yet, high future self-continuity is not necessarily the norm.

In fact, a study from 2009 highlighted that people, at a neurological level, tend to think of their future selves similar to how we might think about some other person – the results of the study showed that thinking of the future self and thinking of an arbitrary celebrity activated the same sections of the brain. As FSC relates to savings, a study from 2014 conducted by a number of the same researchers, concluded that a stranger/self issue impacts savings because “…for those estranged from their future selves, saving is like a choice between spending money today or giving it to a stranger years from now”.

Moreover, researchers also know from social psychology and empathy studies that individuals are more likely to help those that they feel are similar to them. Which means if you feel that your future self is a stranger with nothing in common with your current self… it will be very hard to want to “help” that person. Conversely, increasing FSC makes it easier to relate to and empathize with your future self, and can thus help to increase savings.

Increasing FSC may also help with other more common, and perhaps more difficult, financial planning scenarios like actually transitioning into retirement, getting through a divorce, or thinking about death and other major life-changing events. For example, many advisors have had a client that says they just cannot picture themselves laying on a beach, ever marrying again, or being capable of managing a household on their own – which is both a literal expression of a lack of future self-continuity, and more broadly an example of how humans are very bad at predicting what they will be like, enjoy, or want in the future (which in turn makes goal-based investing really hard because the goals aren’t certain!).

In academic terms, humans are poor affect forecasters, which means we are bad at guessing how we might feel in the future, and unfortunately, we are also bad at guessing the magnitude of how those feelings will affect us. Essentially, we do not know what will make us happy or sad, nor do we know how happy or how sad we may be – we over-estimate and under-estimate our emotions, as described by Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky in their seminal work on prospect theory.

Yet there is hope, as at least some related research has found that scenario planning, a common technique used in financial planning, can help offset bad guessing and potential future disappointment. For example, in one study investigating the impact of scenario planning, participants were asked to make insurance decisions about a valuable personal item. All participants were instructed to select insurance coverage for the item, but only some were also asked to imagine the impact on their future self if that personal item were to be stolen – how would they feel, and what would they do to replace the lost item? The participants that went through this second step, envisioning their future self, were more likely to select optimal insurance.

FSC may offer the same benefits through its three-pronged approach, which examines the similarity between perceived current self and future self, vividness of future self and future scenarios, and the level of positivity associated with the future self.

To illustrate this point, let’s consider the following hypothetical client example.

Example: Jamie is 45 years old and has come to you for retirement planning. Jamie has been a great saver over the past 20-ish years and has amassed a well-diversified nest egg – for all intents and purposes, Jamie is a great client. However, as you begin to work through the financial planning process, you uncover that worker-Jamie (her current self) cannot picture retired-Jamie (her future self). Jamie loves to work, and thinks being ‘retired’ sounds boring and purposeless. Basically, while Jamie has been a diligent saver in the past, she has no idea how she will transition into retirement, because she has no connection to a vision of her retired self. And now that she is having doubts about the purpose of her retirement savings, she has started to ignore tasks related to following her financial plan.

Jamie feels no connection to her future self, and in fact, she thinks of her future self as “purposeless”. Jamie is unable to envision her future life with vividness, and also lacks positivity as it relates to her future. Given these issues, it is going to be very difficult for you, the financial planner, to build a plan for Jamie that she will engage with and follow. As such, Jamie may be a prime candidate for a little FSC assistance.

How To Measure And Use Future Self-Continuity Techniques In A Financial Planning Office

So how might a financial advisor create a process that helps engage with and improve a client’s future-self continuity in a financial planning meeting… given that most FSC research is done by hooking patients up to electrodes to test and measure their reactions and advisors will likely need a ‘less invasive’ setup? (But let me know if you have clients that are open to being strapped to electrodes and running around as avatars – I have some experimental ideas that I would love to test out!).

First, advisors can measure FSC to get a handle on how close a client feels to their future self. Researchers have developed a simple method to test a person’s FSC using two questions, and a variation of graphics, as follows:

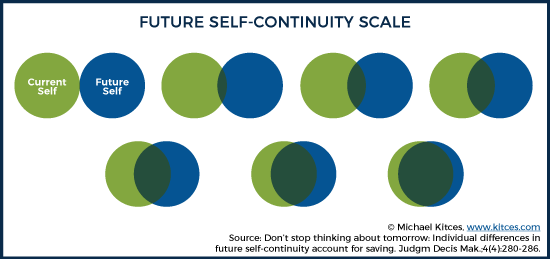

1. How similar and connected do you feel to your future self, ten years from now?

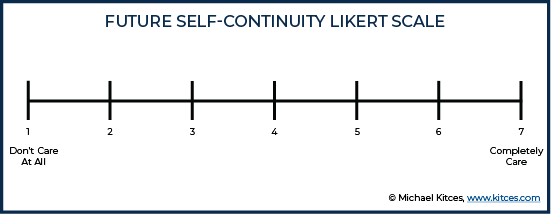

2. How much do you care and like your future self, ten years from now?

In response to question #1, the client would choose from set of given images representing relationships between ‘current self’ and future self’ (an example of which is shown below). In response to question #2, the client would respond on a rating scale with annotations representing a spectrum of choices (e.g., ranging from “don’t care at all” to “completely care”).

This tool to measure FSC could be used as part of a client intake form, or it could be used as part of an interactive ‘retirement-planning’ exercise (more on that momentarily). Either way, the results can give the advisor an idea of just how well (or not) goals-based planning may work. Because clients who are very connected to their future self may only need to check in with you once a year, and probably only need to re-evaluate their plan every 5 years, while conversely, clients who are very disconnected from their future self may benefit from more frequent follow up meetings, perhaps every six months, and may need a plan update each year.

Face-aging technology is another FSC tool that is a little more interactive, and there are a number of inexpensive and safe examples (such as the Changemyface.com website, AprilAge software, a simple face-aging phone app like AgingBooth, or the face-aging filters in popular apps like Snapchat) that can help your clients meet their future selves as part of a retirement or scenario planning activity. When a client sees their own face aged, as per the FSC research, this helps clients identify a vivid future self, employing one key area of FSC theory. And after showing your client a rendering of their future self, you can next engage the other aspects of the theory – identifying the similarity between current and future self, and exploring the positivity held for the future self – which may be as simple as asking the client questions about their future self, ultimately helping them create a relationship with their future self, and also guiding the client to think about themselves, their behaviors or goals, and their emotions in those scenarios. Questions might include:

- What is one trait that you value about who you are today, that you want to be sure is a part of who you are in retirement?

- What is an activity that you enjoy doing today, that you would like to ensure you can do more of in the future when you retire?

- What relationships do you value currently, that you want to be sure your future self continues to cultivate?

Advisors may also consider having clients create a “vision board”, consisting of a collage of images and/or phrases, to represent their future self and goals. This can be done using websites such as Pinterest, or it can be done the good old fashioned way with magazine cutouts and tape. Moreover, while vision boards might really sound strange for a traditional financial planning client meeting, they can be ‘marketed’ as a retirement exercise that can encourage clients to give it a try. And, hey, if the simple fact that it works for Oprah isn’t enough, there is also a growing body of research that also supports the use of vision boards for future goal-setting.

For advisors uncomfortable with face-aging technology and art projects, another great way to help a client engage with their future self is to have them write a letter to their future self. Writing letters to the future self is a common practice used in leadership training exercises and higher education programming. Both the act of writing the letter to pen future goals, and receiving the letter at a given time in the future to be reminded of those goals, can be very powerful. Specifically, as it pertains to the latter (being reminded of one’s goals by an ‘earlier’ self, which can prompt personal reflection), clients will find it much more difficult to ignore whether or not they have been taking steps towards their goals when they’re effectively being held accountable to the expectations set by their younger selves to themselves. Thus, it can be either a wake-up call, or an opportunity to reflect on the progress they have made.

There are a variety of methods advisors can use to introduce clients to the idea of writing a letter to their future self. One way relies predominantly on advisors themselves. After the financial plan has been presented and agreed upon, the financial planner can work with the client(s) to write a letter about their goals and the tasks pertaining to those goals. For example, the advisor can guide the client through creating a bulleted task list with ways to increase savings, obtain life insurance, or to update a will. A second option relies more directly on the client. Financial planners can introduce the idea of the client writing a letter to their future self, explaining that it is a powerful exercise relating to goal-setting and task achievement. Then, again, once the financial plan has been presented and agreed upon, the client(s) can spend 20 or 30 minutes to write a letter to themselves pertaining to the goals they have committed to, and the tasks at hand that they intend to complete in order to progress towards those goals.

In each scenario, the last step is for the financial advisor to take the letter and to mail it out to the client at a later point in time, such as halfway between when the client wrote the letter and when the next meeting is scheduled. The client should receive the letter after enough time has passed, allowing them to settle back into their normal routines, but with still enough time to adjust their behavior (if needed), before meeting with their advisor again.

Ultimately, the key point is that FSC tools (such as focused discussions, face-aging technology, vision boards, and letter-writing exercises) can help bridge the psychological gap between the current and future self. In so doing, advisors can guide their clients not only to identifying future goals that make sense for them, and clarifying the tasks required to achieve those goals, but improving the client’s own buy-in and follow-through to implement and achieve those goals.

In other words, while the advisor’s responsibility is to help their clients and provide advice, the reality is that even more can get done when the client and the advisor are on the same page working diligently toward the same goals. FSC provides a highly personalized way for advisors to connect with clients and to help them build their financial self-efficacy by improving their ‘personal’ connection to the future self they’re planning towards and trying to achieve… which makes the advisor’s job and the client’s financial plan more fruitful and enjoyable for all parties involved.