Executive Summary

Gifting is a common planning topic discussed between advisors and clients – often raising questions about which gifts are taxable, need to be reported to the IRS, or may be exempt from reporting altogether. The rules around gifting are nuanced and can create confusion for clients, but advisors with a clear understanding of gifting strategies can guide them toward informed decisions.

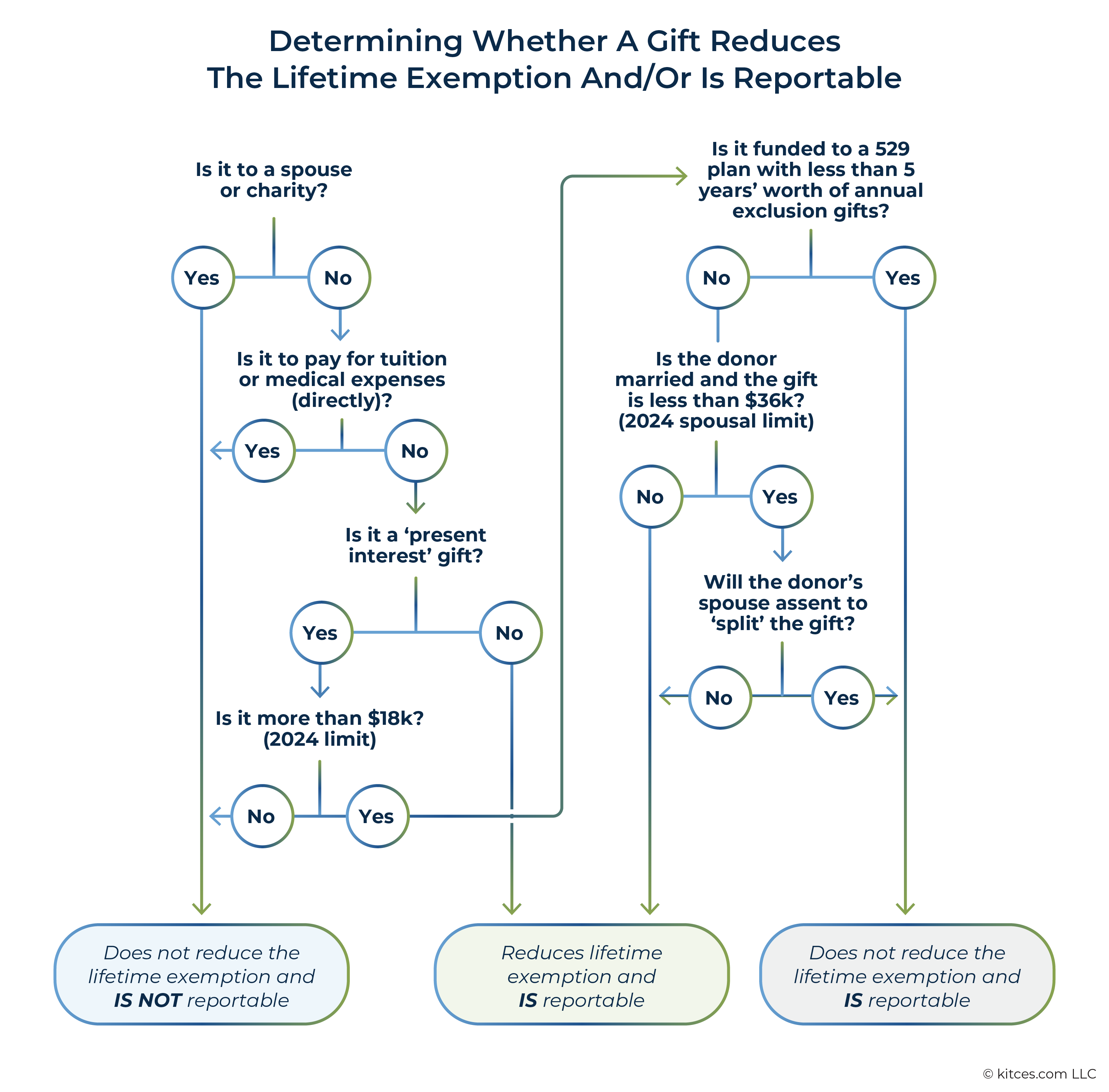

While all gifts could technically be considered taxable to the donor, the annual gift tax exclusion (currently at $18,000) provides for a practical allowance that makes it unnecessary to track and report every small gift (because no one wants to spend time accounting for the value of birthday gifts like bikes, books, or cash!). Furthermore, every individual also has a lifetime gift and estate tax exemption ($13.61M per recipient in 2024). Both the annual gift tax exclusion and the lifetime gift and estate tax exemption come with various nuances that determine what counts toward these exemptions.

For clients looking to give sizable gifts, advisors can help navigate any tax implications by considering how the gift will be given. For example, direct gifts (e.g., those given by cash or check) are simple transfers from donor to recipient, with no limitations on how the recipient can access the gift. On the other hand, gifts in trust allow donors to maintain some degree of grantor-retained control over the recipient's access, which can safeguard the assets under certain circumstances (e.g., divorce, poor decision-making, or claims by creditors). Finally, there are some contributions that get special treatment. For example, transfers into a 529 plan are considered gifts for tax purposes, even though the donor retains significant control over the transferred funds. And gifts of tuition payments made directly to an educational institution or medical expenses paid directly to a medical provider are exempt from both the annual exclusion and the lifetime exemption, meaning that these can generally be made ‘tax-free’ regardless of amount.

Ultimately, the key point is that despite the many complex rules relating to gifting, clients will rarely be required to pay taxes on a gift. They would need to have both an ultra-high net worth and a desire to gift a substantial portion of their estate during their lifetime to be subject to a gift tax liability. For clients who do fall into those categories, advisors can help them implement relevant gifting strategies to minimize gift tax (e.g., by 'gift-splitting' for spouses or dividing gifts across multiple tax years). For others, advisors can offer them peace of mind by clarifying which gifting situations are actually applicable and when they might be obligated to file with the IRS to help them better understand gift taxes. All of which can do a great deal for clients aiming to make the most informed decisions possible!

Gifting is a topic that will come up with perhaps the majority of clients, yet it's a concept with rules that are riddled with nuance and confusion. The Internal Revenue Code has a litany of laws relating to the taxability of gifts, but in reality, rarely will a client actually receive a tax bill for something they gifted. However, while a gift may not mean the client incurs a tax, it may still require the client to notify the IRS about the transaction. Without a clear understanding of the rules surrounding gifting, clients might gift less than they desire for fear of a tax bill or fail to report a gift to the IRS when they should have. Luckily, there are strategies available to help a client accomplish their gifting goals without the added stress of using their tax exemption or reporting the gift to the IRS.

First, it's important to understand why the government seeks to put a tax on gifts at all. Quite simply, a person could avoid the estate tax by simply giving everything away before they die. The gift tax is essentially a 'backstop' for the Federal estate tax. Fortunately, not all gifts are taxed or even need to be reported. This isn't necessarily an act of generosity by the government, but a practical recognition of the incredible burden that would be required to track every small gift (including birthday gifts!). Since its initial implementation in 1932, the gift tax has evolved, becoming unified with the estate tax. However, its evolution hasn't eliminated confusion, as "Will I be taxed on this gift?" remains a common client question. Therefore, it is important to understand how the gift tax works – not only to alleviate fears and misconceptions but also to guide clients in making informed gifting decisions.

The Mechanics (And Misconceptions) Of Taxable Gifts

All Gifts (That Don’t Meet An Exception) Are Taxable… To The Donor

The first key concept is that nearly all gifts are considered "taxable gifts". This means, theoretically, that without allowances or exemptions, the gift would be subject to taxation. However, it's important to note that a gift is taxable only to the donor of the gift, not the recipient. That means that regardless of the size of a gift, the recipient generally won't incur any tax liability (unless an agreement existed for the donee to bear the liability).

Obviously, we know that an actual tax liability won't result from every gift (otherwise, occasions like birthdays and Christmas would get really pricey) – which is why it's essential to understand the many gift tax exemptions that exist. These exemptions are critical for determining whether any tax consequences (or lack thereof) apply when giving a gift.

Nerd Note:

It's important to note that even though a donee may be free from a gift tax liability, income taxes may still apply if they had received a carryover basis for the gift. For example, if the donee were to sell gifted property with carryover basis, they would realize a capital gain based on the original donor's basis in the property.

Furthermore, while a donee who sells a gift of appreciated property with carryover basis would have a capital gain liability, there would be no benefit to the donee for selling a gift of property that the donor held at a loss, because the recipient would not be able to take a loss on gifted property. Therefore, it typically behooves a donor to realize a capital loss by selling the asset and then gifting the proceeds rather than transferring the 'underwater' asset in-kind.

The Lifetime And Annual Exemptions

There are 2 major gift tax 'exemptions':

- The lifetime gift and estate tax exemption (currently $13.61 million per person); and

- The annual gift tax exclusion (currently $18,000 per individual recipient).

(Notably, as a baseline, gifts to spouses who are U.S. citizens and qualified charities will not be a substantial part of the gifting discussion, as such gifts enjoy unlimited deductibility.)

The lifetime gift and estate tax exemption represents the amount a taxpayer may leave to heirs at death without incurring a tax liability. It is the combined total of the taxable gifts made during their lifetime plus what's left in their taxable estate at death.

For example, if a client died having given $2 million in gifts during their lifetime and had a remaining estate valued at $10 million at the time of their death, they would still have no tax liability associated with their estate because the total value of the gifts plus remaining estate is $2 million + $10 million = $12 million, which is less than the exemption amount of $13.61 million.

However, it is important to realize that not all gifts will reduce the lifetime exemption amount. That's because each person also has an annual gift tax exclusion, which is the amount a taxpayer may gift each year without resulting in a reduction of their lifetime exemption amount. Unlike the lifetime exemption (which is reduced by the total gifts regardless of recipient), the annual exclusion may be used on each individual recipient.

For example, if I have 3 children and gift them each $15,000 this year, I can use my annual exclusion on each child's gift. This is because the exclusion applies per recipient, meaning I can use it each year as many times as I'd like – as long as each gift goes to a different recipient!

But let's take the example one step further to show how the annual exclusion and lifetime exemption may interact. Let's say that instead of gifting $15,000 to each child this year, I wanted to give $20,000. Since $20,000 is higher than the annual exclusion amount of $18,000, I would be reducing my lifetime exemption amount by $2,000 on each child's gift. Therefore, after completing my gifts and using my annual exclusions for each gift, my lifetime exemption would be reduced by ($20,000 – $18,000) × 3 = $6,000, reducing my lifetime exemption from $13,610,000 to $13,604,000.

Not all gifts are eligible for the annual exclusion; only "present interest" gifts are eligible. This essentially means that if the recipient cannot immediately access and use the property they were gifted (i.e., they don't have a "present interest" in the gift), then that gift should reduce the lifetime exemption amount dollar for dollar (even if it was under the annual exclusion limit).

For example, if I gifted $18,000 into an irrevocable trust for my child's exclusive benefit, but there was a restriction that prevented the child from accessing the money until they reached age 30, that would not be a present interest gift because the child wouldn't have the ability to use the property until a future date. Which means the $18,000 gift would not be eligible for the annual exclusion and would reduce my lifetime exemption amount by $18,000.

Nerd Note:

Gifts to minors (who are not legally capable of managing their own finances in many respects) can still qualify as a 'present interest' gift if the property is accessible by the minor by age 21. This is in line with most states' Uniform Transfer to Minors Act (UTMA) laws.

However, in some states, transferors are permitted to restrict a minor's access to an UTMA account until after age 21 (usually as late as 25). This may call into question whether the gifted property to an UTMA account, where age 25 is elected as the age of termination, qualifies as a 'present interest' gift.

As trusts represent a key gifting tool for clients who want to remove assets from their estate and implement the protections and restrictions inherent in a trust (rather than giving the gift outright to the individual), this 'present interest' requirement can be an obstacle to using the annual gift tax exemption and protecting the lifetime gift and estate tax exclusion. In order to get around this issue, clients may provide beneficiaries of the trust with a limited time frame to immediately withdraw contributions to the trust (30 or 60 days). This gives the beneficiary a present interest in the gifted property because they have the legal ability to immediately withdraw amounts contributed to the trust (albeit for a short time frame).

The IRS blessed this approach to creating a present interest gift in a revenue ruling based on a court decision known as the Crummey decision, which resulted in the common technique of creating Crummey trusts. This approach is especially important in the case of Irrevocable Life Insurance Trusts (ILITs), where a grantor needs to routinely make contributions to the ILIT in order to satisfy premium obligations for life insurance policies owned by the ILIT. By permitting beneficiaries of the trust a limited withdrawal period, contributions to the trust to pay premiums can qualify for the annual gift tax exclusion, resulting in no reduction of the lifetime gift and estate tax exemption (provided the number of available beneficiaries multiplied by the gift tax exclusion is less than the total contributed amount).

Importantly, clients should realize that it is almost never the case that a beneficiary would actually exercise their right of withdrawal from the trust during the allotted time period (though the trust would not be able to prohibit it). Instead, the Crummey withdrawal right is just purely inserted as a tool to permit the grantor to use the annual exclusion on contributions to the trust.

There is another special type of gift that does not result in the use of the lifetime exemption or the annual gift tax exclusion: gifting indirectly to an individual by paying their educational tuition or medical costs directly to the service provider. These are gifts that the Internal Revenue Code has carved out as gift-tax-free, regardless of the amount or indirect recipient.

Common Gifting Methods

In addition to the rules on how gifts are taxed, it is also important to consider how gifts are typically made. There are generally 3 types of taxable gifts:

- Direct gifts;

- Gifts in trust; and

- Gifts that meet a special exception in the Internal Revenue Code.

Direct gifts are gifts made to an individual without restriction (e.g., writing a check to an individual who deposits the check into their personal bank account). These gifts are the easiest to track and assess since there's little complexity – the gift is simply transferred from the donor to the recipient. However, the downside is that the donor loses control over how the property is used and exposes it to the circumstances of the donee (e.g., creditors, divorce, or poor decision-making).

Gifts in trust are commonly made by grantors to remove assets from their estate (provided the trust is irrevocable and not within the donor's estate) and enjoy the growth of the gifted assets outside of the estate. Gifts in trust also permit the donor to exercise control over the use of the gifted funds long past the date of the transfer. However, depending on the type of trust and extent of grantor-retained control of the trust, such gifts can come with complex rules relating to what portions of the gift represent a completed gift for tax purposes and (as discussed above) whether the gift in trust can utilize the annual gift tax exclusion.

Gifts that meet a special exception would include transfers that are considered gifts for tax purposes, even when it might seem the transfer was not a fully completed gift. A good example would be a contribution to a 529 plan. Contributions to a 529 plan are considered a completed gift even though the owner of the 529 plan retains significant control over the transferred funds. They have the right to change the beneficiary of the plan and can even make themselves the beneficiary and/or use the account balance for their own benefit (with potential tax implications).

The other unique benefit of 529 plan contributions (solely applicable to 529 plans) is that a donor can 'superfund' a 529 plan and contribute 5 years' worth of annual exclusion gifts up-front! In 2024, this means that a donor could contribute up to $18,000 × 5 = $90,000 to a 529 plan without reducing their lifetime gift and estate tax exemption amount. However, while the law permits the donor to superfund the plan up-front, the donor would still need to live until January 1st of each successive year to utilize the exemption amount for each respective year of the contribution.

For example, consider a client who chooses to superfund a 529 plan with a $90,000 gift in 2024. If the client dies in October of 2025, only 2 years' worth of contributions, or $18,000 × 2 = $36,000 for 2024 and 2025, would remain outside the estate since the client was alive on January 1st of 2024 and 2025. The remaining $18,000 × 3 = $54,000 for years 2026, 2027, and 2028 would be clawed back into the estate for estate tax purposes.

Nerd Note:

If a client wants to gift more than the annual exclusion to a 529 plan but less than the full 5 years' worth of gifts (i.e., between $18,001 and $90,000), they could do so and still elect to have the contribution treated as qualifying for the annual exclusion. The gift would be broken up ratably over the 5-year period.

For example, if a client were to gift $50,000 into a 529 and elect superfunding, they would be using $50,000 ÷ 5 = $10,000 of annual exclusion per year for each of the following 5 years.

Common Misconceptions About Gifting

Given all of these considerations around gift taxes, it might seem silly for many clients to be concerned about gift taxes when making a gift. Because despite the many complex rules relating to gifting, clients will very rarely be required to actually pay taxes on a gift. They would generally need to have an ultra-high net worth and a desire to gift a substantial portion of their estate during their lifetime before gift tax liabilities would become an issue for them. Accordingly, for most clients, the primary concern isn't whether a gift will trigger taxes but rather the potential complexity and administrative expense of reporting the gift to the IRS!

The Ins And Outs Of Gift Tax Reporting

When gifts are made in excess of the annual exclusion (or when they don't qualify for the annual exclusion), they are required to be reported to the IRS on Form 709, US Gift (and Generation-Skipping Transfer) Tax Return. This is the reporting mechanism for the IRS to track how much has been given by a taxpayer during their lifetime and how much of their exemption remains. Once a taxpayer reports a gift and has no exemption remaining, then a gift tax liability is due.

The Form 709 Gift Tax Return is due on the same date as a taxpayer's personal income tax return. Therefore, if a reportable gift is made in any given year, the donor will generally have until April 15th of the following year (plus available extensions) to report the gift to the IRS.

Valuing A Gift For IRS Form 709

Determining the value of the gift to report on Form 709 can be tricky, depending on what is being gifted. Of course, if a donor is gifting cash, then the value is obvious (as the value is simply the amount of cash given). Similarly, if the donor is gifting marketable securities, then the value is readily ascertainable based on the publicly available value of the securities on the date of the gift.

However, if the assets being gifted do not have a fixed, obvious value that can be unquestionably verified, then the onus is on the taxpayer to properly value the asset.

Specifically, the Form 709 instructions state the following:

The value of a gift is the Fair Market Value (FMV) of the property on the date the gift is made (valuation date). The FMV is the price at which the property would change hands between a willing buyer and a willing seller, when neither is forced to buy or to sell, and when both have reasonable knowledge of all relevant facts.

Often, valuing an asset without a readily ascertainable values means that obtaining a qualified appraisal of the gifted property is warranted.

In general, the IRS has 3 years to contest the value of a reported gift. However, that statute of limitations will begin only if an adequate disclosure of the gifted property is made.

The IRS Form 709 Instructions defines adequate disclosure as follows:

In general, a gift will be considered adequately disclosed if the return or statement includes the following.

-

A full and complete Form 709.

-

A description of the transferred property and any consideration received by the donor.

-

The identity of, and relationship between, the donor and each donee.

-

If the property is transferred in trust, the trust's employer identification number (EIN) and a brief description of the terms of the trust (or a copy of the trust instrument in lieu of the description).

-

Either a qualified appraisal or a detailed description of the method used to determine the fair market value of the gift.

Gifts That Don't Reduce The Gift Tax Exemption May Still Be Reportable

As gift tax reporting can clearly be annoying, costly, and burdensome, clients may reasonably seek to avoid the necessity of reporting gifts by only making gifts that are less than the annual exclusion amount. However, clients need to be aware that they will still need to report some gifts, even when they are staying under the annual exclusion limits!

A unique aspect of gifting rules is that spouses can use each other's gift tax exemption and annual exclusion – a strategy referred to as 'gift-splitting'. For example, let's say Anthony intends to gift $30,000 to each of his children, AJ and Meadow. It would appear that Anthony would need to use up part of his lifetime exemption if he were to make the gifts during a single tax year because each gift would exceed his annual exclusion of $18,000 per person. But because Anthony is married to Carmela, they have a combined annual exclusion of $18,000 × 2 = $36,000 per person. Which means that Anthony could gift each of his children $30,000 and not use any of his lifetime exemption by 'gift-splitting' with Carmela.

However, in order to take advantage of gift-splitting, taxpayers are required to make the election by filing Form 709 and indicating that the spouse has assented to it. And that means that even though Anthony may be able to avoid using up any of his lifetime exemption by 'gift-splitting' with his spouse, he would still need to make an election and report the gift on Form 709.

Another common scenario where a gift falls within the annual exclusion limit but still requires reporting is when a taxpayer 'superfunds' a 529 plan. As discussed earlier, an individual can contribute up to 5 years' worth of annual exclusion gifts to a 529 plan. However, this type of gift must be elected on Form 709.

Nerd Note:

A little-known requirement is that if someone must file a gift tax return for noncharitable gifts (typically those exceeding the annual $18,000 limit), they must also report all charitable gifts made during the same year on Form 709. So while a client who makes direct gifts only to qualified charities generally won't have a Form 709 reporting obligation, if they also make reportable gifts to individuals or trusts in the same year that are reportable on Form 709, then the charitable gifts would likely be reportable, too.

As noted earlier, the IRS requires "adequate disclosure", which includes filing "a full and complete Form 709".Therefore, if a taxpayer wants the 3-year statute of limitations on IRS challenges to begin, then the taxpayer should make sure that Form 709 is filed properly, including the disclosure of charitable gifts.

Strategies To Structure Gifts So That They Are Not Countable And/Or Reportable

As most clients are unlikely to gift assets in amounts that would ever result in an actual gift tax liability, the focus often shifts from avoiding gift taxes to minimizing the cost and administrative burden of reporting the gift to the IRS. While not all gifts can avoid reporting, there are ways to structure some gifts to eliminate the need for filing Form 709.

Gift That Don't Use The Lifetime Exemption Or Annual Exclusion

While most gifts (even indirect ones) will reduce a person's annual exclusion and/or lifetime exemption, the law provides 2 major exceptions when neither the lifetime nor annual limit is utilized.

Those 2 exceptions are the following:

- Paying tuition directly to an educational institution; and

- Paying medical expenses directly to a medical provider.

These gifts can be made 'tax-free' regardless of the amount. However, it is important to note that the gifts need to be made by paying the service provider directly. If the donor were to give the money to the individual who then uses the funds to pay the educational institution or hospital, that gift would not meet the exception and would theoretically be counted as a taxable gift. Therefore, if a client gives an individual a gift to be used for tuition or medical expenses, it is important for the client to understand that they may be able to relieve themselves of reporting obligations simply by making sure they send the payment directly to the school or medical provider.

Nerd Note:

There are some situations where it's unclear whether a payment made to a service provider would be considered a gift or not. For example, parents covering the cost of their child's wedding may seem like they are making a taxable gift, but the question arises: Is the wedding an expense for the child's benefit, or does it benefit the parent as well (since they've been waiting for this big day themselves!)?

Crossing Tax Years

One simple way to avoid gift tax reporting is to stay under the annual exclusion amount by spreading a large gift over multiple tax years instead of making it all in one tax year. While this is obviously not always possible depending on the reason for the gift, a client looking to make a large gift might consider whether the gift can be bifurcated across 2 (or more) tax years.

For example, if a client wanted to gift $30,000 to their child in November of 2024, they might choose to split the gift up by giving $18,000 in November and then waiting 2 extra months and gifting the remaining $12,000 in January of 2025. This could help them avoid gift tax reporting obligations.

Structuring The Gift To Avoid Making Reportable Gifts

Sometimes, it's not the amount of a gift that makes it reportable, it's how and to whom it is given.

For example, if one spouse wanted to make a gift in excess of their annual exclusion, they could file Form 709 and make a gift-splitting election to use the combined spousal annual exclusion. However, instead of going through that administrative burden, it may be easier to just give the done 2 separate checks – one from each spouse. Even if one spouse needed to transfer funds to the other spouse to complete the gift, this approach may be simpler than having to file Form 709 (recall that there are no gifting issues between spouses).

Additionally, parents often give gifts to their married children. Rather than gifting the whole amount to their child individually, the parents could instead gift to the child and their spouse. This effectively doubles the annual exclusion amount the parents can give without needing to file the 709!

A belt-and-suspenders approach to gifting could be to have separate checks written by each spouse to each recipient separately (i.e., a total of 4 checks). However, it is generally accepted that a check from a joint bank account is considered made one-half by each account owner-spouse and should not require filing a gift tax return, provided the gift is under the gift tax exclusion threshold. Furthermore, in taking this approach, parents should be cognizant of the relationship between the child and their spouse and consider whether there are any potential control/divorce concerns.

Nerd Note:

For spouses in community property states, gifts of community property from one spouse would automatically be deemed one-half from each spouse, which means that both spouses' exclusion amounts would potentially be reduced. So, if the intent is to only use one spouse's exclusion amount, the gift should be made from separate property rather than community property.

This same concept also applies when choosing to 'superfund' a 529 with 5 years' worth of gifts up front. To avoid having to file the gift tax return, a taxpayer could gift the annual exemption amount each year rather than superfunding all at once, which would require filing Form 709. If the taxpayer doesn't survive until January 1st of future years covered by the superfunded gift, the unused portion of the gift would be clawed back into the estate anyway. However, the benefit of superfunding is the tax-free growth on the large lump sum rather than on smaller incremental contributions, which may be a scenario where the hassle of filing Form 709 could be worthwhile.

When Filing A Gift Tax Return Could Be Beneficial Even When A Gift Is Not Technically Reportable

While it would seem that the goal is to stay under the annual exemption and avoid the necessity of filing Form 709 in the first place, sometimes it may actually make sense to file Form 709 even when it isn't required.

As discussed earlier, the statute of limitations for the IRS to contest a gift valuation starts only after they receive adequate disclosure of the gift (including its value). For gifts of assets that are hard to value, it may make sense for a taxpayer to file the gift tax return to start the statute of limitations clock. For example, if a client gifts their son a collection of valuable baseball memorabilia and values it below the annual exclusion limit, they might be concerned that the subjective nature of the valuation could be contested.

In this case, the client could make the gift and proactively file the return, even though no gift tax is due, solely to start the clock and minimize the chance of a future contest down the road (provided the IRS does not contest the return within the limitations period). That way, the client protects against the risk of the IRS questioning the value much later, especially if the gifted asset increases in value exorbitantly by the time of the client's death, when the estate tax return (Form 706) is filed.

It might also make sense for the taxpayer to file Form 709 to memorialize that a gift did indeed actually occur. For example, parents will often put a child's name on their bank account purely for convenience. This would typically not be considered a gift unless the child were to make a large withdrawal in excess of the annual exclusion amount. This concept, where a person is placed on the title to property for convenience rather than to actually gift the property, is sometimes referred to as "bare title interest" or "naked title interest" – meaning that legal title was given, but not equitable title. However, if the donor actually wanted to gift something that might otherwise be seen as providing bare title, filing Form 709 could theoretically formalize that a gift occurred.

Gifting is an area of the Internal Revenue Code fraught with nuance and complexity. Understanding when a gift is taxable is important, but the reality is that many clients won't approach estate tax thresholds, which makes it even more important to understand when a gift is reportable. Identifying when a client may be making a reportable gift is a key opportunity for financial advisors to provide guidance to clients.

Not only can advisors help them understand their IRS filing obligations, but they can also explore strategies to avoid the burden of filing a gift tax return altogether. Even though filing the gift tax return might sometimes be inevitable, an advisor's insight into navigating the administrative complexities is always valuable and can help a client make informed decisions and ease the burden of tax reporting!