Executive Summary

It is a standard requirement in financial services that financial advisors must first determine an investor’s risk tolerance before making any investment recommendations for their portfolio. Yet in the modern era, good financial advisors don’t just invest a portfolio for growth or preservation of principal alone, but to achieve the investor’s goals, and whatever required return (and associated risk) those goals necessitate. Except in practice, doing so is sometimes impossible – because not all investors are able to tolerate the amount of risk they need in order to achieve their goals in the first place!

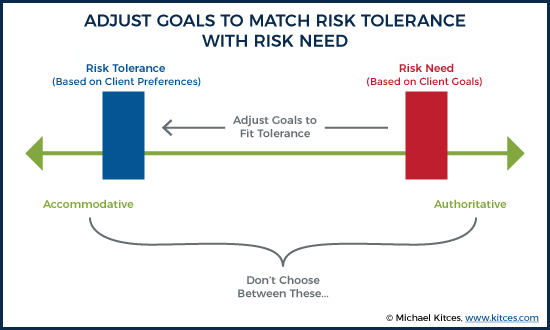

For financial advisors, this leads to two alternative paths for implementation. The first is to take a more “authoritative” approach, where the financial advisor is literally “the authority” – the expert – whose job is to implement whatever the investor needs to achieve the goal (i.e., to invest them for what they need, regardless of their tolerance), and then bears the responsibility to help their clients stick with the plan and stay the course (i.e., “behaviorally manage”) through the inevitable market downturn. By contrast, the second option is a more “accommodative” approach, where the financial advisor may educate and make suggestions to the investor about why they need (and should be more comfortable with) a greater level of risk, but in the end accommodate however the client wishes to invest (since it’s their money and their decision in the end, even if it’s a path inevitably doomed to failure by generating insufficient returns).

On the other hand, arguably the real problem is not just about deciding whether to be more authoritative or accommodative with respect to an investor’s mismatch between their need for risk and tolerance to take it, but recognizing that their need for risk is so (problematically) high because their goal itself is very demanding and risky in the first place. Which means the best path forward may not be about trying to determine the “optimal” portfolio at all (because there really isn’t one) but is instead about helping clients to adjust their goals such that they don’t need more risk than they can tolerate in the first place. In other words, the advisor doesn’t need to be authoritative or accommodating of the client’s high-risk-need and low tolerance if the goals can be adjusted so the client no longer has that high-risk need after all!

Or stated more simply, in a world where portfolios aren’t just invested for growth or preservation of principal in the abstract, but specifically to achieve certain goals, the first step of the process is not to align the portfolio to the client’s risk tolerance, but to align the goals (and the amount of risk they would necessitate) to the client’s risk tolerance in the first place. Because once goals themselves are aligned to risk tolerance… implementing the optimal portfolio turns out to be remarkably straightforward!

The Difference Between The Returns Clients Need And The Risk They Can Tolerate

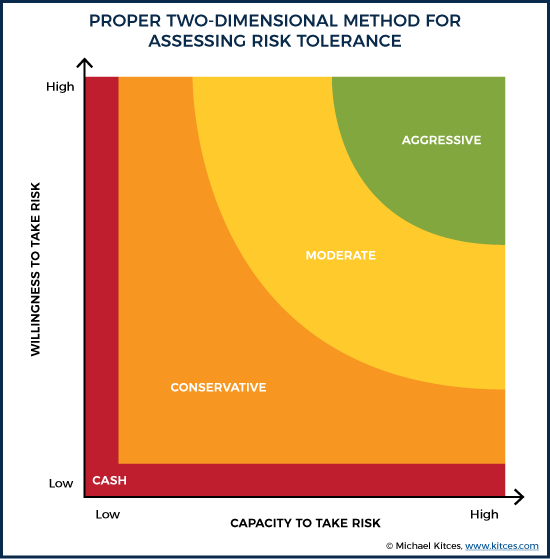

The standard industry approach to risk tolerance is to assess a client’s ability to withstand “risk” associated with their investment portfolio. Both from the perspective of their willingness to stay invested through the inevitable market decline (i.e., their risk “attitude”), and simply their financial wherewithal to be able to stay on track for their goals in the face of market volatility (i.e., their risk “capacity”).

After all, if an investor can’t stay invested in the face of market volatility – if they’ll panic at the bottom, do something hasty or inappropriate, or may outright sue the advisor to blame them for the losses – it’s crucial to know how much of a drawdown an investor can tolerate before they panic. And if the investor must rely directly on those investment assets – e.g., for ongoing distributions in retirement – then an ill-timed drawdown that is too severe can trigger an adverse sequence of returns that outright causes the retirement goal to fail, so it’s crucial to know what kinds of losses the portfolio itself can withstand without derailing the client’s goal.

Thus, designing a proper portfolio essentially entails two different risk “tolerance” constraints – the investor’s attitude or willingness to take risk (without panicking), and the investor’s financial capacity to take the risk (without succumbing to sequence risk).

The caveat, however, is that sometimes the “proper” portfolio based on a client’s aggregate risk tolerance – a two-dimensional combination of risk attitude and risk capacity – doesn’t align with what the client actually needs, in terms of growth/return potential, to achieve their goals in the first place.

Example. Betty Burton is a 63-year-old widow who, after the death of her husband, received a $500,000 life insurance policy payment, and must support herself for the rest of her life with a combination of those insurance proceeds, a modest checking account balance, and a $2,000/month Social Security survival benefit. Betty’s current standard of living requires about $4,000/month to sustain, which means she needs to draw another $2,000/month (or $24,000/year) from her portfolio… an initial withdrawal rate of nearly 5%.

The problem is that in today’s low-interest-rate environment, it’s virtually impossible for Betty to sustain a 5% withdrawal rate from a conservative bond portfolio (i.e., it isn’t sustainable to fund a 5% initial withdrawal rate, adjusting for inflation, with a bond portfolio that only yields about 3%!). At the least, her 5% withdrawal rate spending goal would necessitate a moderate growth portfolio to have enough growth potential in order to even have a chance of sustaining that withdrawal rate in the first place.

However, Betty is actually an extreme conservative investor, who is not tolerant of taking much financial risk at all, recognizing that she will have no other way to make back any losses she might experience. In fact, the reason why she has virtually no other assets for retirement is that her late husband lost the remainder of their retirement savings in a risky real estate investment in the mid-2000s that was wiped out in the subsequent financial crisis and national decline in real estate.

The end result is that Betty needs the returns of a moderate growth portfolio to at least maximize the odds of achieving her retirement goals, but does not have the risk tolerance for such a portfolio in the first place. Yet investing in a portfolio that is consistent with Betty’s risk tolerance will, in turn, have virtually no possibility of achieving the returns needed to achieve her goals.

Which raises the question for the advisor: what do you do in such “impossible” situations, where the client’s tolerance for risk doesn’t match the risk they need to take to achieve their goals?

Authoritative Vs. Accommodative Advisors

In general, most advisors fall into one of two camps when it comes to dealing with clients who have a fundamental mismatch between their tolerance for risk, and the risk they “need” to take in order to achieve their goals to begin with.

The first approach is an “authoritative” one, that positions the advisor as “the expert” who is best positioned to make the call about what is in the best (long-term) interests of the client. The authoritative advisor’s response to Betty’s situation would be something to the effect of:

“Betty will be invested into the moderate growth portfolio she needs to have the best chance of achieving her long-term goals. And my job as the advisor is to help ensure she’s not only invested into this proper portfolio, but stays invested in the portfolio. That’s why Betty is hiring me as the advisor in the first place: to help her implement the best path is to achieve her goals, and to provide the behavioral coaching and support to help her stay the course along the way.”

Notably, the point of this approach is to be authoritative, not authoritarian (seeking to force strict obedience to the advisor for the sake of authority itself). Being authoritative is simply about recognizing that the advisor is being hired because he/she is “the authority” – the expert – and as a result, the knowledgeable and rational expert’s recommendation should be the one that is implemented. For which the advisor then has a responsibility to ensure the client “complies” and sticks with that course of action.

By contrast, advisors at the other extreme take a more “accommodative” approach, recognizing that while the advisor can “advise,” in the end, the advisor must be accommodating to what the client is actually willing to do. Thus, the accommodative advisor’s response would be something to the effect of:

“Betty will be invested into a conservative portfolio that is consistent with her (low) risk tolerance and (low) risk capacity. But my job as an advisor is to educate her of the risk and danger of this path, with a conservative portfolio that may not be able to achieve her aggressive goals, and hopefully to get her more comfortable over time with taking on additional risk to achieve the growth she needs. In the end, though, it’s Betty’s money and Betty’s decision, and my role is simply to support her as best I can with whatever path she chooses.”

A challenge of this dichotomy is that advisors on each side of the authoritative/accommodative divide are likely to disagree with the approach of the other in their handling of the situation. But that’s also the point. They are fundamentally different and opposite approaches, where the accommodative advisor would view the authoritative approach as taking too much control away from the client (in the end, it’s the client’s money!), while the authoritative advisor would likely consider it irresponsible to leave the client on a known-to-be-dangerous path (investing in a portfolio that mathematically cannot achieve their goals).

When Risk Need Doesn’t Fit Risk Tolerance: Change The Portfolio, Or Change The Goal?

Notably, the dilemma of the authoritative-versus-accommodative advisor is focused on how to plug the “right” portfolio into situations where the client’s need for risk (and need for portfolio growth) doesn’t match their tolerance (or capacity) to take the risk in the first place. It is a mismatch that means something has to give – either the portfolio ends out riskier than the tolerance (and the authoritative advisor has an added burden to help the client stay the course), or the portfolio ends out not risky enough for the need (and the accommodative advisor runs the danger that the client will eventually deplete if they can’t eventually be nudged towards greater growth).

However, the reality is that there’s actually a third alternative available, besides trying to solve the tolerance-need mismatch by either being authoritative or accommodative: to help the client change their goals themselves, altering the risk need to bring it more in line with what’s feasible to achieve with the portfolio (and risk tolerance) in the first place!

After all, the real reason why it’s so problematic to determine the “right” portfolio for Betty is not merely a matter of deciding whether it’s better to be authoritative or accommodative to solve the mismatch between Betty’s risk need and risk tolerance. It’s literally that there is a mismatch between her risk need and risk tolerance in the first place. Which is a function of Betty’s goals to begin with.

Thus, imagine that instead of trying to determine whether to authoritatively push Betty towards a more aggressive portfolio, or accommodate Betty in a more conservative portfolio, the advisor helped Betty make a downwards adjustment to her lifestyle spending by 20%, such that she now only needs $3,200/month instead of $4,000/month in the first place. When stacked on top of her Social Security benefits, this cuts Betty’s withdrawal rate from almost 5% to barely 2.5%/year (a $1,200/month portfolio withdrawal on a $500,000 portfolio), which in turn reduces her “risk need” in the portfolio to the point that even a very conservative portfolio (consistent with her low willingness to take risk) will work just fine.

In other words, a conservative bond portfolio works just fine when the goal is reduced to only needing to spend 2.5%/year from the portfolio in the first place. And in turn, the reduced withdrawal rate to 2.5% also eliminates Betty’s exposure to sequence of return risk, as with a withdrawal rate that low, even if a bad sequence of returns occurs, Betty will have more than enough still invested to recover.

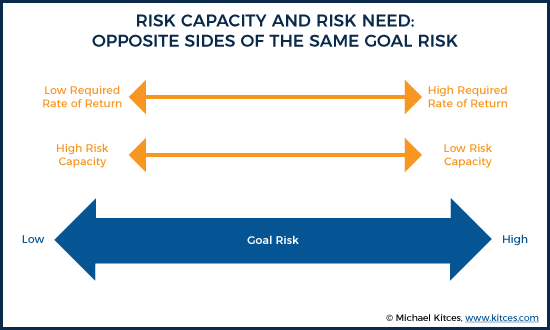

The end result is that changing Betty’s goals not only reduces her risk need, it also effectively increases her risk capacity. As the two are really opposite sides of the same coin. Risky goals have both a high-risk need (must get a high return to achieve them) and a low-risk capacity (very little capacity for something to go wrong, because again the goal needs a high return). While more conservative goals have a higher capacity for risk, precisely because the portfolio doesn’t need to earn much of a return to achieve a conservative goal (i.e., a low risk need).

In fact, arguably the entire challenge of clients whose risk tolerance does not match their risk need isn’t actually a “portfolio” problem in the first place (for which the advisor can be authoritative or accommodative); it’s a goals problem, because the real mismatch is between the risk of the goal (and the risk need it necessitates) and the clients’ risk tolerance. Because by definition, once goal risk (and the need it necessitates) is consistent with the client’s risk tolerance, there won’t be a mismatch of risk need in the first place!

In turn, this suggests that the best course of action for clients who have a mismatch between their need for risk and their tolerance for risk is not deciding where to be (as an advisor) on the spectrum between authoritative and accommodative when recommending a portfolio, but to help the client understand that the mismatch between risk tolerance and risk need represents a fundamental mismatch between their risk tolerance and how risky their goals are in the first place.

Or stated more simply: the best methodology for proper portfolio design isn’t actually about finding the optimal portfolio that fits the client’s risk tolerance, but to help the client identify the optimal goal consistent with his/her risk tolerance in the first place. At that point, implementation is simply a matter of finding the portfolio that naturally fits that goal (and will at that point, by definition, fit the client’s risk tolerance, too!).