Executive Summary

From the rapid growth of goals-based financial planning software like MoneyGuidePro, to the recent announcement that even legendary wirehouse Merrill Lynch will be focusing on a goals-based planning approach, financial planning is on the rise, and is increasingly focusing around an approach of identifying and understanding client goals, and then crafting a plan to help the client succeed in achieving them.

Yet at the same time, the reality is that in practice the goals-based approach doesn't always go as smoothly as hoped. Some clients haven't crafted their goals yet in the first place, while others have goals that are wildly unrealistic and force planners to be the bearers of bad news. Often the goals-based planning process can get mired down in countless iterations of alternative "what if" plans, culminating in a giant physical tome that clients aren't committed to and is never read again after being presented away.

But perhaps the fundamental problem with goals-based planning is simply that it puts the cart before the horse; clients shouldn't be selecting the goals to pursue until they understand what the possibilities are in the first place! Which means in turn, perhaps the best thing that can be done with financial planning software is not use it as an analytical tool to craft a plan to achieve hypothetical goals that may or may not even be realistic, but instead to use the software interactive with clients to explore the possibilities of multiple scenarios and understand the trade-offs just to arrive at what the goals should be in the first place. Once the possibilities have been selected, realistic goals can be chosen, and then a more productive series of financial planning recommendations can be delivered for implementation!

The inspiration for today’s blog post are some additional thoughts I've been having regarding a recent book I read, entitled “Scenario Selling: Technology and the Future of Professional Selling” by former advisor and entrepreneur Patrick Sullivan and psychologist Dr. David Lazenby. As I've written in the past, don't be fooled by the books "selling" title; it presents some powerful ideas about how to better deliver financial planning advice to clients. In particular, the book highlights that despite its increasing popularity, the goals-based planning approach may actually be fundamentally flawed.

The inspiration for today’s blog post are some additional thoughts I've been having regarding a recent book I read, entitled “Scenario Selling: Technology and the Future of Professional Selling” by former advisor and entrepreneur Patrick Sullivan and psychologist Dr. David Lazenby. As I've written in the past, don't be fooled by the books "selling" title; it presents some powerful ideas about how to better deliver financial planning advice to clients. In particular, the book highlights that despite its increasing popularity, the goals-based planning approach may actually be fundamentally flawed.

The Problem With Goals(-Based Planning) – Not Knowing How Big To Dream

For some clients, a goals-based planning process is relatively easy; the clients come in with the details of what they have, where they want to go, and it’s pretty clear how to craft a plan to get them from here to there. They know when they want to retire, where they will live, what they will spend, and their current assets and savings are on track enough that there aren’t any hard conversations and trade-offs necessary, just a series of tactics to implement to get to the goal.

For other clients, though, the process gets bogged down quickly. When asked “what are your goals” the answer is “well, we don’t really know.” They’ve never really thought about it before. Or worse, there are some goals, but the goals are so wildly inappropriate for the resources (assets, income, and ongoing savings) they actually have, that they’re totally unrealistic. At best, crafting a plan is just going to project a catastrophic failure and require a sit-down with the client to come up with a second plan instead that has new, more realistic and feasible goals.

This situation – where some clients have realistic goals and easy plans to craft, while others have unrealistic goals that can’t be achieved with any feasible plan – is perhaps not entirely surprising, though. By analogy, imagine trying to take a long trip in an airplane. It’s not enough to just say “where in the world would you like to go?” Because there’s only so much fuel in the plane, and even with the tank topped up there’s only so far the plane can possibly go given its weight, and there may only be a little bit of wiggle room in the amount of weight that can be shed. In addition, there could be storms somewhere between “here” and “there”, which means the trip will be bumpy at best, or at worst require a workaround (or rather, a fly-around-the-storm), which in turn will just burn more fuel and reduce the range even further.

As Sullivan and Lazenby point out, what this means is that in the end, it doesn’t really make sense to ask “where in the world would you like to go” until you survey the situation, figure out “where in the world can we go, given the plane/fuel and current weather conditions” first, understand the possibilities, and only then decide where to go once it’s understood what is feasible. And in a similar manner, arguably it really doesn’t make sense to just ask clients what their goals are, until they first understand what possibilities are feasible to begin with. In other words, whether it’s flying a plane or charting a path towards retirement (or some other goal), a client can’t decide where they’d like to go until they first know where it’s possible to go first. We just don’t know how big to dream.

Turning Around The Financial Planning Process And Putting Possibilities Before Goals

From the financial planning perspective, this challenge to goals-based planning raises an interesting question: what would it look like if we explored the possibilities first as Sullivan and Lazenby suggest, and selected the goals second (and then crafting the plan comes third thereafter!).

Fortunately, possibilities are something we can evaluate. We have the data to know where the client is today (current assets), and to understand their current trajectory (current income and savings). We can discuss and explore what kinds of adjustments can realistically be made to the path they’re on; how much more could they really save (or not) by changing spending, would it be possible to put in more hours at work and get a raise, how flexible is the retirement date, would it be acceptable if the kids took on student loans for not all but at least some of their college expenses?

With this initial framework, clients can explore the possible scenarios. What would happen if they just stayed on their current path? What if they really did trim current spending a bit to save a little more? How would the projections change if the retirement date is moved, or the allocations are shifted further towards or away from the college goal instead? Does a higher growth rate assumption actually help, or does the additional risk do more harm than good? By looking at the various scenarios, the client can evaluate what is realistically possible and not, as well as understanding which assumptions are really driving the plan and which changes have the most leverage to impact the outcome.

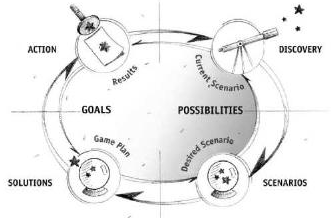

Examining the various scenarios to look at the realistic possibilities – just like assessing the fuel, weight, potential range, and looming weather for our prospective flight – gives the client an understand of what are FEASIBLE, REALISTIC goals in the first place. And THEN the client is better equipped to choose from amongst the goals, prioritize which are most important, evaluate the alternatives to get there, and make choices about which to pursue and which trade-offs are acceptable, and in the process crafting a real, actionable plan with the advisor to get there. Or as Sullivan and Lazenby envision it in their book:

Source: Scenario Selling: Technology and the Future of Professional Selling by Sullivan & Lazenby

Financial Planning Software As A Scenario Learning Tool

So as financial planners, how do we facilitate the Sullivan and Lazenby approach of visioning of possibilities with a client? By using financial planning software not for goals-based planning, but to collaboratively explore possibilities-first scenarios and learn from them.

Ideally, then, financial planning software should allow for clients to quickly change amongst and adjust scenarios, to find where the leverage points are, and see what works and what doesn’t. In this environment, the role of the planner is as collaborator, to help explain/interpret possibilities, the trade-offs they entail, and put context to what’s feasible and what’s not.

Notably, though, this isn’t just about crafting a plan with several “what-if” scenarios. For many (most?) clients, real world financial planning is too complex; when clients don’t know what the possibilities are in the first place, you’d be stuck making 47 different plans just to show them the range of potential outcomes. Consequently, it’s far easier to just use the software interactively, and let them see how the scenarios change with adjustments on the spot. What might have been pages and pages worth of printed plan alternatives can be evaluated with a few tweaks to a slider, and the client can quick evaluate which possibilities are relevant and which are not, and make a real commitment to which they wish to pursue.

Unfortunately, not all financial planning software is capable of doing this effectively; the tools themselves can be so complex that many planners would be afraid to use the software live and interactively with clients for fear of making a software mistake (though in recent years, a number of software packages have become somewhat better!). Nonetheless, along with writing their book back in 2006, Sullivan and Lazenby ultimately created their own years ago, called ScenarioNow, specifically to help facilitate the process of clients evaluating multiple scenarios. And fortunately, in recent years big screen televisions had gotten so much less expensive it really is feasible to put them into every conference room (as this process wouldn’t be nearly so appealing if everyone was crowding around an old 15” monitor!).

The bottom line, though, is simply this: the traditional goals-based planning approach can actually be very problematic when clients don’t understand what goals are possible in the first place, leading to a slow arduous process with lots of questions and lots of alternative plans and what-if scenarios, that are just slowed even further if the planner has to go back to their computer and run new analyses and schedule new meetings with the client just to talk through the “new” results. In other words, it’s hard to analyze goals and craft a plan when clients aren’t certain they’ve selected the “right” goals in the first place! By contrast, when the planning process starts by helping clients to just explore the possibilities – using financial planning software as a collaborative tool to test multiple scenarios and evaluate the trade-offs – and then select the goals with an understand of which are realistic and feasible in the first place, it’s far more practical to move on to the next step where the planner can figure out the best path to help clients achieve what they wish and then implement what’s necessary to get there!

And in the meantime, for those who want a deeper understanding of what possibilities-first scenario learning is all about, I do highly recommend getting a copy of Sullivan and Lazenby's book!

And in the meantime, for those who want a deeper understanding of what possibilities-first scenario learning is all about, I do highly recommend getting a copy of Sullivan and Lazenby's book!

So what do you think? Viewed in this manner, are there “problems” with traditional goals-based planning? Is a possibilities-first scenario approach a better way to help clients figure out their own path to success?

How do you feel Money Guide Pro serves as a tool to accomplish what you mentioned above?

Tony,

I think MoneyGuidePro’s PlayZone is a solid step in this direction, though it is ultimately still something that’s typically used “after” the core plan has been constructed, which is still less than ideal. I think in the ultimate view, you build the plan and watch it take shape live, rather than build one full iteration and THEN start adjusting for possibilities.

Though I don’t really mean that as a ding against MoneyGuidePro. They’re actually further along with this than many other financial planning software tools. I just think there’s still plenty of room to build further in this direction…

– Michael

Michael – great article, and you’re correct about goals based financial planning. Wealth management clients appreciate an interactive planning session where they can see the impact to their financial lives to changes of critical inputs, ex. spending, rate of spending increase, asset allocation, savings, etc. Plus based on my experience, goals based financial planning is somewhat flawed because if clients are unable to successfully fund a critical goal – like college education – they usually find a way to fully or partially fund it from cash flow anyway. Because clients live day-to-day, week-to-week, month-to-month, and year-to-year based on their cash flows, so they understand a cash flow based financial planning model better, and more importantly, it’s actionable. Client knows what they earn, know what they pay in taxes, know what they spend, and know what, if anything, they save. Financial planning software which helps clients dial in an asset allocation and a financial behavioral pattern that yields acceptable projections has tremendous street credibility with clients, and they, therefore, act upon it.

Re: “But perhaps the fundamental problem with goals-based planning is simply

that it puts the cart before the horse; clients shouldn’t be selecting

the goals to pursue until they understand what the possibilities are in the first place”

Couldn’t agree more!

Sadly, most clients are woefully unaware of their options and as a result of compensation structures, the focus of most advisors is on gathering assets and/or making a sale. In my experience, the time spent to explore goals and options is a precious commodity which is rarely valued enough to be an integral part of “financial planning”.

Interesting thought, Michael. I view goal-setting and planning as an iterative process regardless of whether you start with particular goals in mind. I use Monte Carlo to show the odds of success of a particular set of assumptions, some of which are related to the client’s goals — spending in retirement, leaving money behind and so on. If it turns out a goal is unrealistic or not ambitious enough, we have a conversation (much easier in the latter scenario). It also depends on where in their lifecycle a client is — a 55-year-old will generally have more specific goals in mind than a 35-year-old. I recently worked with a couple, a 55-year-old and 54-year-old who had some specific ideas about when they each would retire, how much they would need to spend in retirement and so forth. I ran the numbers and it was clear that they could almost certainly retire earlier than they had planned to, spend more in retirement or some combination of the two. They’re not ready to retire now, though, so I implemented their portfolio based on their original goals and will rerun the numbers every year or two so they can see how they were progressing.

The big problem for me is as you describe: the level of sophistication of my Monte Carlo software makes it too complex and slow for me to use it live and interactively with clients. The inputs are on a number of pages, and after you get them all in, it can take several minutes to run through the thousands of scenarios. It would be painful to do that even once live, let alone several times. I’d love to have something that would do it quickly and elegantly without losing the sophistication of my current program. I just toured the RetireNow Wealth Planning software on the ScenarioNow site. Unless they’ve figured out how to dramatically improve processing speed, it’s not Monte Carlo based. And without that level of sophistication, I wouldn’t trust the results.

Michael, you have taken the words right out of my mouth… again.

100%.

If we are to engage clients in meaningful discussions and advance this nebulous thing called financial planning, then this is exactly the discussion we need to have. In 30 years, i’ve never had a client approach me and say “Brian, I’ve got these lifetime goals, but I’m stuck and I think what I really need is a lifetime cash flow forecast or financial plan”. Why are we marketing this as our solution?

Great article. Must read that book.

All the best

Since ScenarioNow appears out of business (they do not return emails nor could I get the trial to work) does anybody know of an alternative software that is simple enough to work with clients?

Give Financelogix a look.

It allows you to manipulate assumptions on the fly to generate infinite what-ifs, and a Monte Carlo analysis of 2000 iterations takes only a few seconds.

Thanks!

Perhaps the sad truth (sad only because on this forum we seem to be the kind of people who feel planning is a true practice and not a sales strategy) is that planning software is a tool, and tools have a purpose. This purpose has been shaped and driven by an industry which is “for profit” and thus the outcome is a set of tools and presentation styles designed to prompt the investor/would be client to disclose as much of their finances as possible, and what better way to promote discovery than to allow the client to come up with their own carrot, and then having to provide as much information as possible to “help us help them” attain that carrot.

Marco,

It’s worth noting that Lazenby’s book (from which I drew a lot of these concepts) is actually about “Scenario SELLING” in particular.

In other words, while I see so many parallels to this in the world of advice and financial planning, the irony is that Lazenby is pointing out that even if the goal is simply “sales” and “profits” these are actually STILL better techniques for the kinds of complex (financial) problems people face in the real world! 🙂

– Michael

Hi Michael,

It’s rare for me to disagree

with you Michael, but with great respect for all you’re contributing these days

to all of us in personal finance, I would like to offer a different

perspective.

What a great financial planning meeting needs to start the process is Authenticity and Inspiration,not a spreadsheet that will deliver “Possible or Impossible.” If a client is

inspired by their dream, they will find a way to deliver their results. That

won’t be our task. Our task will be to help design the financial architecture

that will deliver it. But our first task is to make the meeting theirs, not

ours, by meeting with them in a way that is authentic for them, not financial,

where they learn quickly to feel comfortable sharing everything in their life

that might have relevance in a conversation around money.

You can’t get to people’s

authentic goals, by using a financial list kind of approach. That approach will

lead naturally to the dilemma you write about, the “Possible or Impossible”

dilemma, which immediately makes it the financial adviser expert’s meeting, not

the clients and not a fiduciary meeting either. Starting with that kind of

meeting most clients won’t tell you what they really care about, what they long

for in their life. They will play your game instead, describing the material

things they might want that they think you want to hear. Possible or Impossible will be the response.

With an authentic, empathic

and inspirational approach, the client will do 80% of the talking, there will

be no spreadsheet in the first meeting or products or “solutions,” and the

client will be comfortable and inspired to find their way to what they really

want, and surprised that it comes up in an advisers office because they thought

you were all about the numbers, and their most passionate goals are more

meaningful than that. What they really want, whether it has to do with family,

creativity or business, values or spirit, community or a sense of place is

almost always doable. It will be delivered by the client’s own passion, particularly

if it is supported by an empathic adviser and the financial architecture he or

she can uniquely provide. The reasons clients have not accomplished these goals

are because they lack these two requirements (architecture and adviser), as

most of our blocked goals have financial excuses like wet blankets all around

them.

The real issue here is:

1. What are the questions that will inspire and bring an authentic response?

2. How do you ask the questions?

3. How do you listen (way before you get to the obstacles or even to the questions)? Listening is the most important skill, empathic listening, listening for the dream of freedom.

4. How then do you deliver the freedom the client desires and solve the obstacles?

If your focus is authentically on what freedom means to the client, and your own passion is to

help deliver it, you will virtually never experience the Possible/Impossible

dilemma or any of the obvious flaws in a “list of goals” approach to client

relationships in financial planning.

Here are some resources

I recently wrote a column for

FPA Journal that explains why Life Planning creates entrepreneurial endeavor,

which is why the Impossible/Possible dilemma needn’t come up. Here is a link to

blogger Aries Jimenez’ copy of the article: http://sandiegowealth.co/2014/10/28/a-favorite-article-aries-jimenez/

My most recent book and free consumer website (there is an adviser

Life Planning website as well) are meant to help consumers either find an

adviser they can trust, or learn to do Life Planning for themselves. Advisers get

referrals from the free consumer site. The site has many of the questions and

tools to use with clients: http://www.LifePlanningForYou.com

And the best way I know (andI know I’m biased) to learn this is in the 5 day training part of the

Registered Life Planner® certification program through http://www.KinderInstitute.com.

I’d love to entice you to the one I’mgiving in Hana Maui (with two of your fans, David Oransky and Reed Fraasa)December 7-12, or in Dorset, UK January 11-16 or May 3-8 in Boston. I know you’re a busy man, but I’d love to see you. Bring the family to Maui!

Much aloha from Hana,

George

George,

Thanks for your feedback.

I have to admit, I’m a bit puzzled though, because I see nothing you’re saying here as disputing the point of the article.

Have the discovery meeting. You’ll note that even the graphic above includes this discovery meeting.

The point is “what are you trying to come to at the end of that meeting, and WHAT HAPPENS NEXT”? Are you having this discovery meeting to discover goals that the client wants to pursue? Great. What then? What if the goals are unrealistic? What if the completely financially-uneducated client has this discovery process to come to a series of goals that will require millions of dollars they don’t have and cannot achieve? How does THAT conversation get facilitated?

At some point, there needs to be an exploratory process around the goals themselves. You seem to have inferred that will involve “spreadsheets” and “financial lists”, but that was not presented in this article. And you seem to have inferred that this will replace having an authentic client conversation, but that was not presented in this article either.

Again, the point remains: AFTER you do your meeting, BEFORE you present a final plan with action items for the client, how do you CONNECT what you learn in discovery to get to realistic achievable goals for which the client can take action?

Respectfully,

– Michael

Very good thoughts. The challenge we have found with goals based planning, and the reason it comes in second or third, if at all, is that many haven’t set specific goals. There are many reasons. Some people aren’t in the habit of dreaming of what’s possible, many haven’t stopped to think in terms of goals or outcomes, before they come see us, and most aren’t aware of what their assets and cash flow could accomplish. So, a large part of our initial work, in the discovery phase, is spent on these kinds of discussions.

Another challenge with goals based planning is that life is fluid, instead of static. A top priority this year may not make the top five or ten next year, if life changes.

There is more, but it’s all in line with Michael’s thoughts.

Hi Michael, do you know whats happened to these guys, their website is not working?

Michael, you are so incredibly helpful. Thank you for all the information you provide. I am also an XY Planning member, so this comment might be more appropriate there. Would you record a series of meetings so I can visually see what these financial planning meetings might look like? I have not had the benefit of a mentor and I would love a visual.

I notice that the two hyperlinks to Sullivan & Lazenby’s work are now broken. Is their software and book still available and relevant?