Executive Summary

Social Security spousal and survivor benefits were created to provide some level of Social Security benefits to households that relied primarily on a single worker, as a means to both financially support households with stay-at-home spouses, and to ensure that an earner’s widow was not left in poverty after the primary worker passed away. The caveat, however, is that in the early years of Social Security, some government workers had the opportunity to participate in jobs that did not pay into Social Security (so-called “non-covered” jobs), and instead directly received a private pension… with the end result that, in addition to their pensions, they also ended out receiving Social Security spousal and survivor benefits as though they were a stay-at-home spouse, when in reality they were simply a working spouse in a non-covered job.

To address this concern, Congress passed the Government Pension Offset (GPO) rule over 40 years ago to more fairly determine how Social Security benefits would be received by such non-covered government workers to ensure they were not effectively “double-dipping” into government pension benefits as workers and spousal and survivor benefits intended primarily for non-workers. Today, the GPO affects more than 695,000 Social Security beneficiaries.

The core of the GPO rule is that workers who receive pensions from government jobs that did not participate in Social Security will face a reduction of spousal and survivor benefits that they might otherwise be entitled to based on the work records of their spouses (who worked in covered jobs that did pay into Social Security). Specifically, the GPO rule applies to individuals who meet three criteria: 1) worked at a federal, state or local government job where they did not pay Social Security taxes; 2) qualified for a pension from that job (that did not pay into Social Security); and 3) are eligible to receive spousal or survivor’s benefits from a spouse who did work in a job covered by Social Security.

For those who are affected, the GPO reduces spousal and survivor benefit amounts by 2/3 of the government pension benefit received from the non-covered employer. And if 2/3 of the retiree’s pension exceeded their spousal or survivor benefit altogether, the net result is that they will receive none of that Social Security benefit at all! Importantly, though, this rule applies only to the person who actually owns (i.e., originally earned) the non-covered pension. Which means that if a retiree inherits their spouse’s non-covered pension, their Social Security survivor benefits are not reduced because the pension was originally owned by and based on the work history of another.

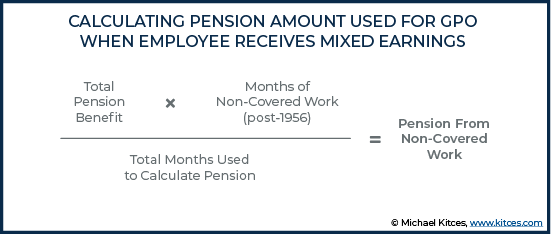

In some cases, an individual may have pension benefits based on earnings from covered and non-covered employment (having switched jobs over the years between employers who both paid into the pension). In these situations, the GPO will reduce the individual’s benefits by 2/3 of the pension portion attributable only to non-covered employment. This non-covered pension portion is determined by multiplying the full amount of the pension benefit by the ratio of non-covered months of employment to the total months of employment contributing to the pension.

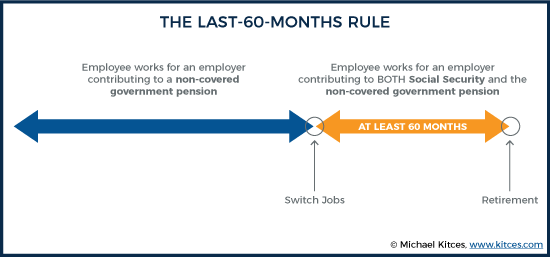

While the GPO is generally difficult to avoid, there are a couple of strategies that financial advisors can consider for their clients who may be impacted by the rule. The “Last-60-Months” exception says that the “GPO does not apply if an individual was covered by both the government retirement system and Social Security throughout his/her last 60 months of Federal, State, and local government service. The 60 months need not be consecutive.” Thus, if a worker leaves their current job under which they would have been subject to the GPO, finds new employment that is covered by Social Security and the government pension, and stays in that job (or another job that contributes to the government pension and that is covered by Social Security) for at least 60 months of service prior to retirement, the GPO rule would not affect their Social Security spousal or survivor benefit.

Alternatively, a government employee has the option of withdrawing from their pension altogether. For this strategy to avoid the GPO, the worker would need to withdraw all of their own contributions (with interest) from the plan, forfeiting any employer contributions (unlike most non-government pensions, many government pensions consist of both employee and employer contributions). This strategy should be considered carefully, as while the GPO impact on Social Security benefits would potentially be eliminated, so too would any pension benefits to which the individual was once entitled (and the loss of the pension itself may easily end out costing more than the otherwise foregone Social Security benefits would have been in the first place!).

Ultimately, the key point is that advisors should be aware of when and how the Government Pension Offset may affect their clients, and if their clients can use a strategy to mitigate the GPO’s impact on their benefits. While there are stirrings of legislative proposals to eliminate the GPO rule (along with the WEP), the population actually affected by these rules is relatively small (approximately 1% of all Social Security beneficiaries in 2018 were affected by the GPO). Thus, traction on any amendments to eliminate or modify these rules may be difficult, especially since there arguably are good policy reasons for it to exist (to avoid the implicit ‘double dipping’ of earning a non-covered pension as a worker and a spousal or survivor benefit nominally intended for non-working spouses). In the meantime, advisors can help their clients by understanding when the GPO needs to be factored into a client’s financial plan, especially given that the GPO can heavily (or fully) eliminate Social Security spousal or survivor benefits that they might have otherwise anticipated receiving!

While the U.S. Government Accountability Office reported in 2015 that 96% of all workers are covered by Social Security benefits, only 56% of the workforce was covered in 1937, the first-year contributions to the program were made. As back in the early days of Social Security, certain groups of workers were excluded from coverage, including Federal government employees (who generally already had separate Federal retirement benefits) and state government employees (because, at the time, the constitutionality of Federal taxation on state wages was a questionable point).

In the 1950s, Congressional amendments to Social Security allowed states to enter into voluntary, irrevocable “Section 218” agreements with the Social Security Administration, which allowed state employees to participate in the Social Security system for the first time… and in the process, adjusted (and sometimes reduced) their own state pension liabilities to coordinate with the additional Social Security benefits their employees would instead receive.

But with most states entering into such Section 218 agreements, making Social Security benefits available to these states’ government workers, some policymakers became concerned that these workers, who were able to retire with their pension and potentially still draw full Social Security benefits for themselves (and their eligible dependents) by subsequently working in another job where they paid into the Social Security system, had an unfair advantage by ‘double-dipping’ into the system (and in particular, the higher Social Security replacement rates that otherwise apply to “low-income” workers).

Thus, the Social Security Administration introduced two rules that were intended to address this concern – the Windfall Elimination Provision (WEP) in 1983, and the Government Pension Offset (GPO) in 1977 (which was later amended in 1983).

The lack of understanding around these complex rules can potentially lead individuals who were at some point in jobs not covered by Social Security (or who had spouses working in such jobs) to make bad decisions about their retirement based on inaccurate information on their Social Security statement (which generally does not include WEP or GPO adjustments). And because Social Security income serves as the backbone of a successful retirement for many clients, financial planners are responsible for ensuring that they understand how the WEP and GPO rules work and that they can provide sound recommendations to clients affected by these rules.

Notably, while WEP and GPO both deal with situations where an individual has been a participant in a pension from a job not covered by Social Security, WEP and GPO apply in different situations. Accordingly, this post will focus only on the Government Pension Offset (GPO) rule, including how the GPO works, and the strategies that can be used to maximize the benefits for clients who are potentially subject to the GPO.

(Editor’s Note: A previous discussion of the Windfall Elimination Provision (WEP) can be found here.)

Why Does The Government Pension Offset (GPO) Rule Exist?

In 1977, the Social Security Administration introduced an amendment implementing the Government Pension Offset (GPO) to address policymakers’ concerns that workers who received a pension from a Federal, state, or local government job, not covered by Social Security, were 'double-dipping' by also receiving spousal or survivor benefits that were nominally intended for beneficiaries who hadn’t worked and were financially dependent on a working spouse for benefits. After all, had the individual worked in a job covered by Social Security, they typically would not have received Social Security spousal or survivor benefits, because their own individual Social Security benefit would be higher (which they would have received in lieu of any spousal benefit).

By participating in a government job not covered by Social Security, though, the worker essentially was able to earn a pension during their working years and a Social Security spousal or survivor benefit as though they had never worked (because with a non-covered job, they are considered to have “never worked,” for Social Security purposes).

In essence, the GPO rule was meant to simulate the “dual entitlement” provision, which states that “a person's benefit amount can never exceed the highest single benefit to which that person is entitled.”

For example, if a retiree is entitled to a monthly retirement benefit of $2,000, and a spousal benefit of $1,200, the dual entitlement provision would limit this retiree’s benefit to the $2,000 individual retirement benefit, since it is larger than the spousal benefit. And in theory, the fact that the individual received a (likely higher) pension from a non-covered job that didn’t participate in Social Security shouldn’t undermine the impact of the dual entitlement rules.

Accordingly, individuals who are subject to the GPO rule include those who meet the following criteria:

- Worked at a Federal, state, or local government job where they did not pay Social Security taxes;

- Qualified for a pension from that job (that did not pay into Social Security); and

- Are eligible to receive spousal or survivor’s benefits from a spouse who did work in a job covered by Social Security.

If an individual meets these criteria, the GPO reduces those Social Security spousal or survivor benefits to which the individual would otherwise be entitled based on their spouse’s work record. At the end of 2018, more than 695,000 people were affected by the Government Pension Offset.

One notable difference between the WEP and the GPO is that while the WEP is triggered by a pension from any non-covered job, the GPO is only triggered if the pension is a “government pension” as defined by the Social Security Administration. Thus, the effect of this distinction is that some non-covered pensions (such as foreign pensions) will trigger the WEP but not the GPO.

The Impact of the Government Pension Offset (GPO) on Social Security Spousal And Survivor Benefits

Essentially, the GPO rule reduces the amount of Social Security survivors’ or spousal benefits for beneficiaries who also receive non-covered government pension benefits from their own work (i.e., they did not pay Social Security taxes through that job).

To figure out how much the GPO may reduce a retiree’s Social Security benefits, first figure out how much of a regular, normal spousal or survivors’ benefit they could receive. Then, take the gross amount of their pension from non-covered employment, and subtract two-thirds of that from the spousal or survivors’ benefit amount.

Example 1: Ann worked as a schoolteacher for 30 years, and her husband, Robert, was an accountant for a private firm. Ann’s teaching years were spent in Texas, one of the 15 states where teachers are not covered by Social Security.

When Ann retired, she began receiving her Texas Teachers’ Retirement pension of $3,000 per month. Robert retired at the same time and filed for his Social Security benefits. He began to receive $2,200 per month from Social Security, based on his own work record.

If Ann had simply been a homemaker who didn’t qualify for her own Social Security benefits, she would be entitled to a 50% spousal benefit of $1,100. However, because her non-covered pension benefit was $3,000, and 2/3 of that benefit ($2,000) is greater than the spousal benefit she would have received, Ann is not entitled to receive any spousal benefit based on Robert’s work record (the reduction amount of $2,000 exceeds the actual benefit of $1,100). Just as Ann would not have received a $1,100/month spousal benefit if she had her own $2,000/month Social Security retirement benefit.

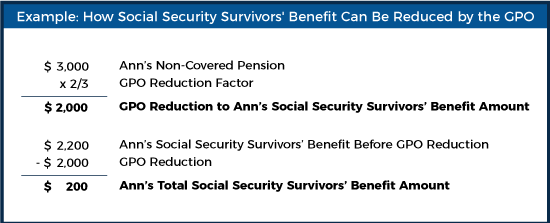

Sadly, when Robert passed away two years after retirement, Ann was devastated. While she thought she would be entitled to receive a full Social Security survivors’ benefit of $2,200 (based on 100% of Robert’s benefit), she was unpleasantly surprised to learn that the GPO rule “offset” that benefit as well, by $2,000 (2/3 of her $3,000 pension), leaving her with only a $200/month survivors’ benefit, calculated as follows:

Thus, Ann and Robert’s total household monthly retirement income was reduced from $3,000 (Ann’s pension) + $2,200 (Robert’s Social Security benefit) = $5,200 before Robert died, to $3,000 (Ann’s pension) + $200 (Ann’s Survivors’ benefit from Robert’s Social Security income) = $3,200/month once Ann was widowed.

Retirees can be shocked to learn that their spousal or survivors’ benefits are reduced or eliminated by the GPO rule – especially if their original financial plan included an assumption that this stream of payments would be available as part of their total retirement income.

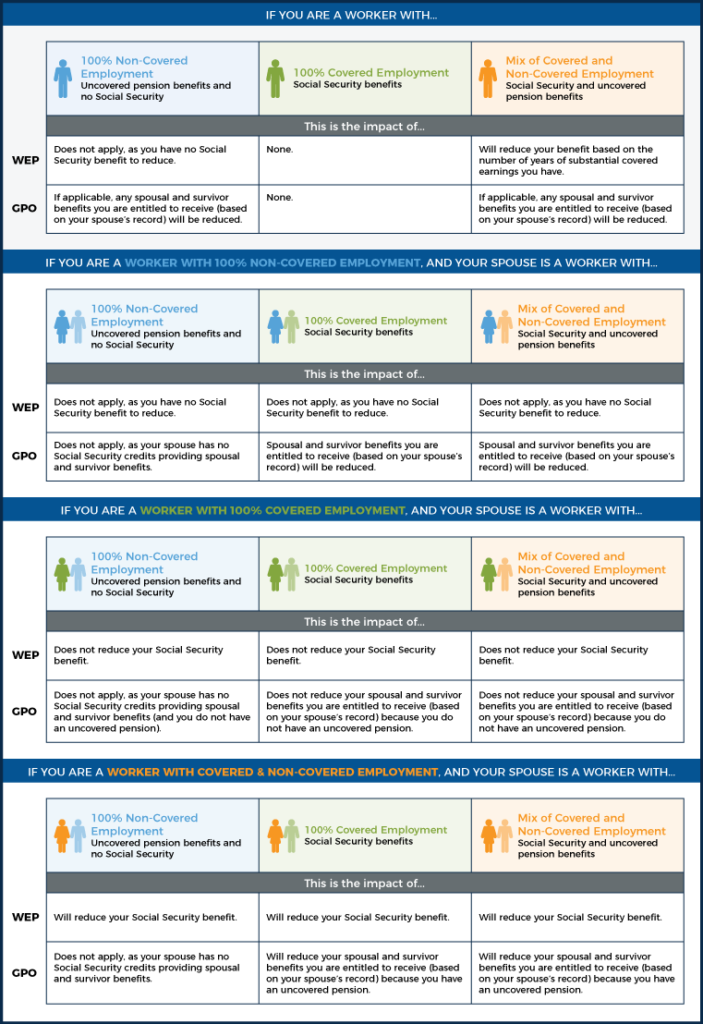

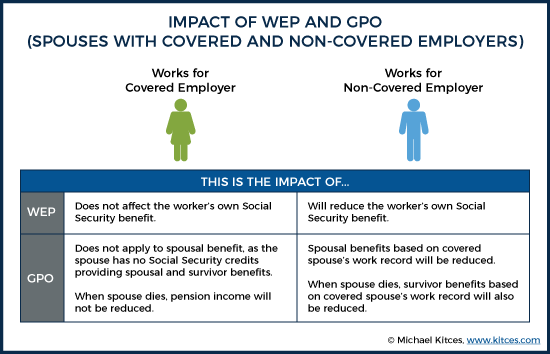

The chart below summarizes how the GPO rule (and the Windfall Elimination Provision) affect workers and their spouses who have covered and uncovered forms of employment.

What If a Retiree Inherits Their Spouse’s (Non-Covered) Pension?

One common question often asked by workers affected by the GPO rule is, “If I leave my pension payments to my spouse, will that cause the GPO to affect their Social Security benefit after I die?”, because it is natural to believe that if an employee names their spouse as the beneficiary on their pension from non-covered work, the same penalties could apply to the surviving spouse.

The short answer is no – a surviving spouse’s own individual Social Security benefits would not be affected if the other spouse with the non-covered pension named them as a beneficiary on that pension.

The Social Security Administration addresses this issue succinctly in its Program Operations Manual System, which states:

The GPO applies to a spouse’s benefit for any month the spouse receives a pension based on his or her government employment not covered under Social Security.

Thus, as long as the surviving spouse did not have non-covered pension benefits of their own, the GPO rule would not affect the inherited income from a non-covered pension originally belonging to their deceased spouse.

Reducing the Social Security Penalty Imposed by the GPO

There are two ways for retirees to minimize the effects of the GPO on their Social Security benefits. Both could potentially require some drastic moves, but depending on the retiree’s situation, one of these options may make sense for them to use.

GPO Strategy #1: The Last-60-Months Rule

The first strategy allows a worker to avoid the impact of the GPO by using what’s called the Last-60-Months Rule. According to this rule, the GPO reduction doesn’t apply “if you are receiving a government pension and the last 60 months of your government employment were covered by both Social Security and the pension plan that provides your government pension” [Social Security Code of Federal Regulations Section 404.408a(b)(6)]. Furthermore, the employment does not necessarily need to be full-time; according to the Social Security website, “covered employment during at least 1 day in a given month constitutes a month of service for purposes of meeting the 60-month requirement.” However, during these last 60 months, the worker is not permitted to work for any non-covered employer at any time.

In other words, an employee must leave their current job under which they would have been subject to the GPO, find new employment that is covered by Social Security and the government pension, and stay in that job (or another job that contributes to the government pension and that is covered by Social Security) for at least 60 months of service prior to retirement. These 60 months do not necessarily need to be consecutive.

Thus, it is crucial for retirees using this strategy to be very careful not to mix employment during the period that counts as their 60 months of employment (even if it is just for one day); otherwise, the GPO rule may end out compromising their Social Security spousal or survivorship benefits.

The Social Security Administration explicitly states the following:

If at any time during the last 60 months of government service, the individual worked in non-covered employment under the retirement system that provides the pension, the individual’s spousal benefit will be subject to GPO. GPO will apply, with regard to that pension, even if the individual concurrently worked in another position with the same or a different employer covered by Social Security.

While the conditions required for the last-60-month rule may not often easily be met by non-educators, this strategy can be a viable option for workers in some school districts. Depending on an individual’s state of residence, there may be a number of community colleges or school districts that participate in both Social Security and the state teachers’ retirement pension program, where the educator could switch jobs within the school system to move into a Social-Security-covered job for their last 5+ years to eliminate exposure to GPO.

Example 2: Dave has been working for the Austin Independent School District (ISD) in Austin, TX for the last five years (60 months). Before that, he worked for the Lancaster ISD in Lancaster, TX for 30 years.

Lancaster ISD participates in the Texas Teachers’ Retirement System (TRS) only (and not Social Security), while Austin ISD is a school district that participates in both Social Security and the Texas TRS.

By switching school districts and staying with the Austin ISD for at least 60 months, Dave’s Social Security spousal or survivor benefits from his spouse will be exempt from the GPO rule because his current employer 1) participates in Social Security, and 2) covers the state government pension plan (i.e., the TRS pension).

Had Dave stayed at Lancaster ISD, his Social Security benefit would have been reduced by 2/3 of his gross pension benefit.

But would it be worth the hassle of a late-career change for an employee simply to exempt themselves from the GPO?

Advisors can help their clients analyze their options by illustrating future values of spousal and survivors’ benefits to make a decision. Here’s an example of what this could look like:

Example 3: Pebbles currently works at Bedrock Community College (BCC) and makes $60,000 per year as a faculty lecturer. She has a pension with the Bedrock Teachers’ Retirement System that will provide a $3,000/month benefit when she retires.

Pebbles’ husband Bam-Bam works as a miner at the local quarry. He expects to receive a Social Security benefit of $2,500 per month when he retires at full retirement age.

Pebbles would normally be eligible for a spousal benefit based on Bam-Bam’s record of $2,500 x 50% = $1,250/month. However, if Pebbles’ spousal benefit is reduced by the GPO rule, her monthly benefit will be $1,250/month– $2,000 (2/3 of Pebbles’ $3,000 pension) = $0. (As Social Security benefits cannot be negative!)

Pebbles plans to retire from her current job in two years. However, she just learned about the last-sixty-months rule that would potentially eliminate the impact of the GPO rule on her spousal and survivor benefits, and consequently is considering leaving her BCC job to work part-time at the Bedrock University Student Store. Her salary would be reduced to $12,000, but her “new” employer would be paying into both her Bedrock TRS pension and Social Security.

If Pebbles stays at her current job and retires from BCC in two years, the future value of her $60,000 annual salary at retirement would be $121,748 (assuming a 6% discount rate adjusted for annual salary increases of 3%), with no spousal benefit.

If Pebbles takes the part-time job at BU and works for five more years, the future value of her $12,000 annual salary at retirement would be $63,598 (again, assuming a 6% discount rate adjusted for the same 3% annual salary increase). Because her spousal benefit would no longer be subject to the GPO rule, the present value at retirement would be approximately $205,278 (assuming she receives the benefit for 20 years after retirement and adjusting the 6% discount rate with a 2% annual cost-of-living adjustment). Thus, the total value of her salary and spousal benefit at the time of retirement would be $63,598 + $205,278 = $268,876.

By working for five more years and removing the GPO rule reduction of her spousal benefit, the value of Pebbles’ salary and spousal benefit at the time of retirement would be estimated to be about $268,876 - $121,748 = $147,128 greater than if she were to retire in two years working at her current, full salary.

Notably, if Bam-Bam dies first, Pebbles would also be eligible for a survivors’ benefit of $2,500 – $2,000 = $500/month if she retires from BCC as a lecturer. If she takes the part-time BU job and stays for five years, her survivor’s benefit would not be reduced by the GPO rule, and she would be entitled to the full $2,500/month benefit. Which would produce another $2,000/month for life for all the years that she outlives Bam-Bam by avoiding the GPO!

GPO Strategy #2: Withdrawal from a Pension

The second option to reduce the GPO penalty is for an employee to completely withdraw from their pension plan. This option is rarely used, as the employee’s withdrawal of their contributions and interest generally results in a forfeiture of future rights to the pension altogether, potentially giving up a lifetime of accumulated benefits. (In many cases, state workers with pension plans are required to contribute their earnings to participate in the plan, unlike most standard non-government pension plans where pensions consist only of employer contributions.)

Notably, unlike the withdrawal option for the WEP, where employees must withdraw contributions before they are eligible to receive a pension, the withdrawal to avoid the GPO can be completed before or after eligibility requirements for the pension have been met.

Here’s what the Social Security Administration says about this:

Withdrawals from a defined benefit plan, before or after eligibility for the pension, of only employee contributions plus any interest (i.e., none of the employer contributions are included in the withdrawal), and whereby the employee forfeits all rights to a pension, are not pensions for GPO purposes. This rule applies even if the employer paid the employee contributions for the employee (i.e., some employers may pay for the employee’s contribution). Any other separation payment, withdrawal, or refund that consists of both employer and employee contributions from a defined benefit or defined contribution plan is a pension subject to GPO.

When using this strategy, financial advisors should make sure their client only receives the amount they contributed, plus any interest. If any of the employer contributions are included in the withdrawal, they will still have forfeited their pension but would now be subject to the GPO.

In many cases, it just doesn’t make sense to withdraw from the pension plan. Sure, an individual and their beneficiaries may receive full Social Security benefits based on the individual’s own Social Security record if they can avoid the WEP and GPO... but they also forfeit their rights to the income stream generated by their pension. For this reason, it generally doesn’t make sense to pursue this option, and a careful cost-benefit analysis needs to be done to ensure the right decisions are made based on the client’s unique circumstances.

How Mixed Earnings or Mixed Employment Affect the Government Pension Offset Rule

In some unique instances, workers have “mixed earnings”, where they work for a period of time for a government employer who contributed to their pension but didn’t pay into Social Security (a non-covered pension), and later for an employer who contributed to the pension plan and also to Social Security (but not long enough or in the right sequence to qualify for the last-60-months GPO exception).

While mixed earnings affect how the Windfall Elimination Program (WEP) reduces a worker’s Social Security benefit, they have the most impact on how the GPO rule is applied.

Simply put, if a worker has a pension from mixed earnings, the entire pension amount should not be used in calculating the two-thirds reduction! Instead, only the amount that came from the months where the worker did not pay Social Security taxes is actually used in the GPO calculation.

The Social Security rules make this clear:

Some entities may pay a pension based on both government employment and private employment. For pensions based on a combination of federal, state, or local government employment and private employment (i.e., non-government employment), GPO applies only to the portion of the pension based on government employment.

For months with both types of earnings, a month that contains both covered and non-covered employment is considered a covered work month.

Unfortunately, though, determining the impact in practice is not always straightforward, as while the Social Security Administration implies it is simple to verify the amount of a worker’s prorated pension by requesting the information from the employer, it is not always a straightforward process to obtain the information.

By reviewing a retiree’s employment records (to determine periods of work for covered and non-covered employers) and Social Security earnings history, the following formula can be used to calculate the pension amount from non-covered work:

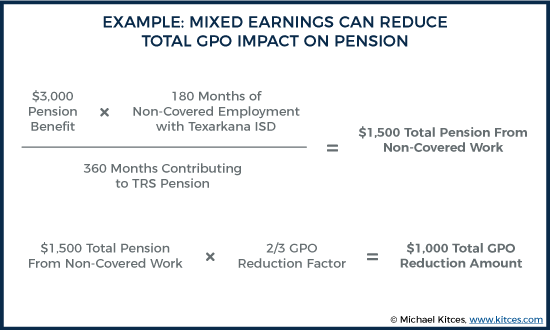

Example 4: Denise worked at Austin ISD for 15 years, where she paid into both Social Security and TRS. After her husband died, she moved to Texarkana and started working for Texarkana ISD, where she spent the last 15 years of her teaching career. While in Texarkana, she paid into TRS only, with no payments into Social Security.

Her TRS pension provided her with a benefit of $3,000 per month. When she filed for benefits, they told her (incorrectly!) that the GPO rule would reduce any spousal or survivors’ benefit by $2,000 (which is two-thirds of her $3,000 pension). With a survivors’ benefit of $2,200 at full retirement age, this would have left Denise with a monthly benefit of $200.

Fortunately, Denise’s financial advisor recognized this error, and determined that her survivors’ benefits would only be reduced by $1,000, which is 2/3 of the portion of her pension that was earned during the years she did not contribute to Social Security (while working for Austin ISD), calculated as follows:

The full amount of Denise’s monthly survivors’ benefit is $2,200 at full retirement age. Using the correct calculation of the GPO reduction amount, Denise’s survivor benefit will be $1,200/month.

By correcting this error, Denise’s advisor saved Denise from losing out on $1,000 per month of survivors’ benefit!

How 403(b) Plans, 457 Accounts, and ORP Factor into the GPO Rules

Many government employers offer supplemental retirement plans in addition to their pension plans. Specifically, there are workers in certain community colleges and universities who are given a choice between their state’s Teacher’s Retirement System (TRS) or an Optional Retirement Plan (ORP).

These plans generally vary on a state-by-state basis, but essentially, certain higher education employees can opt out of TRS in favor of a defined contribution plan that allows them to make their own contributions and get a match from their employer. The dollars in the plan can be invested in a variety of ways, similar to 401(k) plans, giving employees a choice of how to save for their retirement needs.

But how does a distribution from such a plan trigger the GPO rule? This answer depends on individual employers.

Here’s what the Social Security Administration handbook says:

Payments from a defined benefit plan or defined contribution plan (e.g., 401(k), 403(b), or 457) based on earnings from non-covered government employment are pensions subject to GPO regardless of the source of contributions (employer only, employee only, or a combination of both), if the plan is the employee’s primary retirement plan. If the plan is a supplemental plan, the payments are subject to GPO when the plan payments contain employer or both employer and employee contributions.

Essentially, if the 403(b) or 457 is a supplemental plan and only contains a worker’s contributions, it will be subject to neither WEP nor the GPO reduction.

However, if the plan is a worker’s primary plan, or if it is a supplemental plan and only contains an employer’s contributions, it will trigger both calculations.

Learn How to Work with the GPO and WEP Rules Because They Are (Probably) Not Going Anywhere

Although many workers affected by the GPO (and WEP) are anxiously awaiting legislation that will someday repeal these rules, it isn’t likely that Congress will do so anytime soon. There have been multiple proposals to repeal GPO and WEP over the years, but none have successfully passed.

The bill that had the most promise, The Equal Treatment of Public Servants Act of 2015 (HR 711), was sponsored by the Chairman of the House Ways & Means Committee. If any bill had a chance of success, that one did. But even that proposed legislation would have simply replaced the WEP with a new (roughly similar) formula and did nothing for the GPO.

This doesn’t mean it can’t happen, but when something only affects 4% of the population, as these provisions do, it’s hard to get momentum behind change. Especially when there are arguably sound public policy reasons for the rules in the first place (to prevent an implied 'double-dipping' of non-covered workers getting Social Security spousal and survivor benefits intended for non-working [not just non-covered] spouses).

Financial advisors and planners simply need to work with the fact that these rules exist – though fortunately there are strategies that can help clients affected by the rules to reduce the impact these rules have on their benefits.

Advisors can also help clients by adapting their financial and retirement plans accordingly, targeting successful outcomes even in the face of these penalties or restrictions. To ensure that, at a minimum, if WEP or GPO do apply, they aren’t an unfortunate surprise that only comes when it’s too late because potentially irrevocable retirement decisions have already been made!

Michael,

Thank you for your insight as always. I read your content on WEP and GPO and have questions. I have a complicated case I’m working on and I’d love additional resources if you have them. The client works for a TX college in an administrative role and when I read her paystub I see both TRS and OASDI. When she called the Social Security office they told her that WEP would not be an issue but that GPO would be. How do i find out what portion of her $2,000/pension would be used in the GPO calculation you referenced?

Good articles on these SSA provisions and nuances….My understanding is that the GPO might also effect a spousal benefit if the client/spouse doesn’t take the pension but rolls over his/her benefit to an IRA instead of taking a monthly pension…

Can someone confirm this please?

Got hit with the GPO when turned 66 and tried to collect one-half of wife’s Social Security. Prepared me for the Windfall Elimination Provision. Big complaint is that the yearly social security mentions possible reduction due to WEP but no indication that it applies to one specifically. Kind of a gotcha you learn when you apply. However lucky to have collected spousal benefit and waited as that is now being phased out.

Can you explain what you mean about the phased out? Are you saying you were able to collect spousal benefit in addition to pension? If so, how?

Firstly, I am sparring with SS in that I have a “pension”. Still awaiting answer to my March appeal to not apply WEP (did not object in time to GPO). But back to the spousal benefit – I believe that anyone born after 1954 no longer qualifies. You need to research but believe Congress removed this benefit.

The “covered” and “non-covered” income earned by one person as outlined above describes situations where the pension was still receiving contributions from both employers. Are the rules the same when the “non-covered” worker retires from the federal/state/local job and then their next job they are paying into social security but NOT their pension?

I have a slightly different situation. I worked enough in social security paying jobs to gain credit and receive SS. I also have 25 years in TRS which I am retiring with this December. My husband has 31 years in SS and now is accruing 3 years in TRS but can’t retire yet. At this point it is my understanding I will be eligible at 67 for reduced SS benefits based on my pension, but not eligible at all for my husband’s SS if he dies. Since I DO have several years in the SS system, but not in the last five, does that affect GPO or WEP? If not, can I sub (which pays SS) for a few years while drawing TRS and overcome the GPO?