Executive Summary

“Happiness” is highly valued in our society, and the “pursuit of Happiness” as an ideal is even embedded within the U.S. Declaration of Independence. However, “happiness” can mean different things in different contexts. In a very broad sense, the term may align with something along the lines of Aristotle’s “eudaimonia” that was meant to refer to the ultimate aim of humans to live a good life. However, in recent years, a narrower conception of “happiness” has emerged – particularly within psychology and economics research. Based on a desire to evaluate how factors such as income are related to “happiness”, researchers have come up with survey questions such as “How happy are you on a scale of 1 to 3” that are then used to test all sorts of hypotheses regarding the relationships between life circumstances and happiness.

There’s nothing intrinsically wrong with such research; however, studies based on this narrow conception of happiness tend to make for good headlines and often get widely cited in the media (e.g., “People who drink coffee are happier!”). As a result, such studies can gain traction to the point that they could actually influence life decisions, and that can be problematic.

First, there’s the issue that personality is actually one of the strongest predictors of “happiness” (as reported in such studies). For instance, all else being equal, extraverted individuals simply tend to report they are “happier” than introverted individuals when presented with such survey questions. Moreover, extraversion is associated with all sorts of life decisions (e.g., living in cities), which means that we can’t make much of research findings that don’t consider how personality factors influence results. For instance, if survey respondents who live in cities report that they are happier than those who don’t, are they “happier” because city life makes people happier? Or is it simply the case that more extraverted people live in cities and are also more likely to report they are happy no matter what their life circumstances? And beyond that, even if it’s true that city living makes some people happier, it does not necessarily follow that an introvert who likes to live in the mountains would be happier if they were forced to relocate to a city.

More fundamentally, however, is the issue that this narrow conception of happiness (i.e., happiness that can be rated through shallow inquiries such as, “How happy are you on a scale from 1 to 3?”) is not an effective way to choose life goals that will actually bring a person long-lasting feelings of fulfillment. Researchers have criticized the notion that people should chase these narrower forms of happiness, rather than orienting one’s life toward the pursuit of meaning and purpose – which often comes from accomplishments that take work and are not easy.

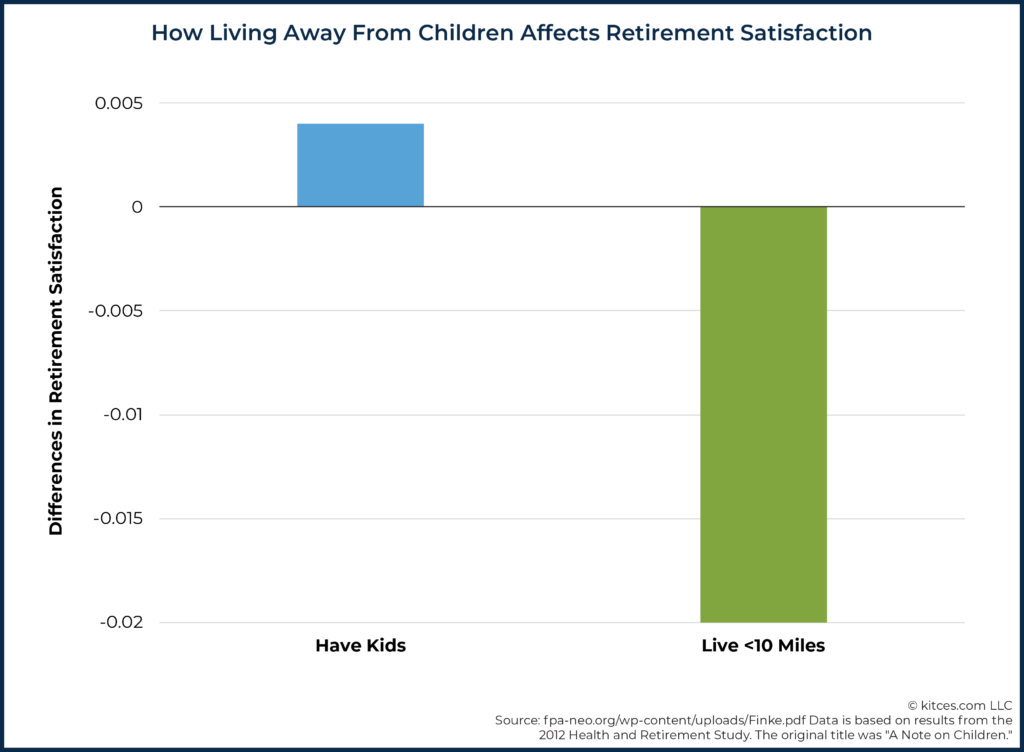

A common example of how media has hyped happiness studies within a personal finance context comes from Michael Finke’s oft-cited finding that parents who live near their children in retirement are less happy than those who don’t. Notably, the relationships between living near children and happiness in retirement are often tiny, and even Finke and his coauthors found that they were non-existent when controlling for other factors. Such studies also generally can’t control for other factors such as personality or the possibility that factors such as declining health (and therefore children moving to parents rather than vice-versa) are the actual factors driving the observed (tiny/non-existent) relationships.

But more fundamentally, no one lies on their death bed wishing they’d averaged 2.5 rather than 2.4 on their lifetime happiness score when measured on a scale from 1 to 3. However, many people do lie on their death beds wishing they’d spent more time with family, built better relationships, or otherwise engaged in pursuits that brought a sense of purpose and meaning. That’s even true – and perhaps particularly so – when pursuits that brought purpose and meaning were challenging and required sacrifice. Ultimately, unless we’re truly indifferent between two alternatives or realize we’ve made some life decisions without giving much conscious thought, happiness studies are simply not a great way to make life decisions. Instead, we are generally better served thinking about what we know about ourselves, and relying on that to guide our important decisions in life.

Happiness is something that we often seek. “Life, liberty, and the pursuit of Happiness” is deeply embedded within American culture. However, what we mean by “happiness” is often not quite clear. In a very broad sense, often the term is merely meant to reflect a 'good life' – this may even be akin to what Aristotle referred to as eudaimonia (i.e., the ultimate goal of human life – perhaps meaning, purpose, and fulfillment – that is much more than a fleeting or momentary state of happiness or other positive emotion) – but there are narrower conceptions of happiness that are commonly used as well.

One such narrower conception of happiness is captured within psychological research. For several decades now, researchers have attempted to measure and quantify happiness in ways that allow for examining how it relates to other factors in life.

A common approach is to ask someone a question like, “In general, on a scale from 1 to 10, how happy do you feel?” This narrower conception of happiness is then generally used in studies that examine questions such as, “Does more income lead to greater happiness?”

Researchers trying to answer such questions have the challenge of coming up with a valid and reliable measure of happiness. Often what researchers have landed on is a series of questions – typically somewhere between 1 and 5 questions – that ask people to broadly assess how happy they feel in life.

It is likely apparent at first glance that such conceptions of happiness may be quite limited. Deirdre McCloskey, Distinguished Professor of Economics, History, English, and Communication at the University of Illinois at Chicago, has criticized such measures for the narrowness of the conceptualization of happiness:

But nowadays there is a new science of happiness, and some of the psychologists and almost all the economists involved want you to think that happiness is just pleasure. Further, they propose to calculate your happiness, by asking you where you fall on a three-point scale, 1-2-3: “not too happy,” “pretty happy,” “very happy.” They then want to move to technical manipulations of the numbers, showing that you, too, can be “happy,” if you will but let the psychologists and the economists show you (and the government) how.

On a long view, understand, it is only recently that we have been guiltlessly obsessed with either pleasure or happiness. In secular traditions, such as the Greek or the Chinese, a pleasuring version of happiness is downplayed, at any rate in high theory, in favor of political or philosophical insight. The ancient Chinese sage Zhuangzi observed of some goldfish in a pond, “See how happy they are!” A companion replied, “How do you know they are happy?” Zhuangzi: “How do you know I don’t know?” In Christianity, for most of its history, the treasure, not pleasure, was to be stored up in heaven, not down here where thieves break in. After all, as a pre-eighteenth-century theologian would put it – or as a modern and mathematical economist would, too – an infinite afterlife was infinitely to be preferred to any finite pleasure attainable in earthly life.

Despite the narrowness of modern attempts to quantify happiness, an entire field of psychological and economic research has emerged around such measures, and research journals such as The Journal of Happiness Studies were developed. Over time, this field has grown and matured, providing some valuable academic insights. Yet, at the same time, the narrowness of the type of “happiness” studied is often underappreciated, and that can be a significant mistake if one becomes overly reliant on research findings about “happiness” to guide their own life decisions.

A primary concern with the practical application of such research is the narrowness of the type of happiness in discussion. University of Toronto psychologist Jordan Peterson has said [verbal speech edited for readability]:

Most of the time in life, there's at least one serious thing going wrong. You have a relative who's not well, or you have financial difficulties, or there's a problem in a relationship. Life is hard, and there's often something going wrong.

And so, if what you want is to be happy and most of the time there's something serious going wrong, then that's not going to work out very well for you. What I recommended in 12 Rules for Life – and what I think wise people have recommended since the beginning of time – is that you look for meaningful engagement and significance and responsibility instead of happiness.

Because that can keep you afloat during tragic and troubled times. And that's better than happiness. It's not like I'm against happiness. If it comes your way, embrace it. But it's a gift rather than something that's a proper pursuit.

Notably, when Peterson says happiness is not “a proper pursuit”, he is talking about “happiness” in the narrow sense – not in a eudaimonic sense such as Aristotle’s articulation of the ultimate pursuit in human life. Moreover, what Peterson describes as what we should pursue in life – engagement, significance, responsibility – is all well-aligned with Aristotle’s eudaimonia.

And this is an important insight because often actions we take in life that do bring about engagement, significance, and responsibility – or perhaps, more generally, “meaning” – can be at odds with bringing about conditions that would leave us inclined to rate ourselves highly on a happiness survey.

For instance, raising children is hard work. A 30-year-old with lots of time for leisure, hobbies, and socializing might very well rate themselves higher on a 10-point happiness scale than a sleep-deprived 30-year-old juggling childcare and other life responsibilities.

While it certainly is not the case that everyone wants to have children, many people do find the experience of having and raising children to be one of the most meaningful things they do in life. And it’s in part the challenge of raising children that gives the experience meaning. Likewise, anyone who has long struggled toward some pursuit – be it in business, fitness, art, or any other domain of life – can appreciate how the challenge of the journey itself is what brings about feelings of meaning, pride, and accomplishment.

Peterson captures this well in a quote from his book, 12 Rules for Life:

Perhaps happiness is always to be found in the journey uphill, and not in the fleeting sense of satisfaction awaiting at the next peak.

Ultimately, what McCloskey and Peterson both describe is a far richer and more humanistic conception of what the proper aims of life are, based around striving for a fulfilling life of purpose and meaning; it’s not, as McCloskey quips, the “calculative hedonism of 1-2-3.”

The research on happiness is arguably one area in which the desire to empirically measure everything – a scientism of sorts – has degraded our understanding of what it means to live a good life. Time-tested wisdom that comes from thinkers such as Aristotle – and repackaged by modern thinkers such as McCloskey and Peterson – is likely more useful for serious reflection on how we ought to set our aims in life.

For now, we can leave the shallowness of modern happiness measures as one of many significant limitations of contemporary research on happiness, but we’ll return to this topic later with a specific example of how this “calculative hedonism of 1-2-3” can conflict with a richer understanding of developing a meaningful life in an example from retirement research.

The Role Of Personality In Influencing “Happiness” Assessment

A significant issue with being overly reliant on contemporary happiness research to make life decisions is that there are known biases that influence how people fill out happiness surveys and that have nothing to do with living a ‘good life’ at all.

In particular, personality traits have been consistently shown to be one of the strongest predictors of assessments of different forms of “subjective well-being” (e.g., happiness, life satisfaction, financial satisfaction, etc.). My own dissertation – and a paper from my dissertation recently published in Personality and Individual Differences – examined this topic specifically.

To be clear, personality traits – which are largely stable over time and hard to change – are not just one of many factors that influence subjective well-being assessment, but one of the strongest factors in influencing how people rate their happiness via survey questions.

In other words, one of the strongest explanations for how people rate their happiness at any given time is simply their temperament and how they tend to respond to such questions generally.

For instance, traits of extraversion (i.e., characterized by excitability and outgoing sociability) and positive affect (i.e., enduring positive sentiments rather than just momentary positive emotions) are highly correlated with one another and are two of the strongest predictors of happiness. So, if you give two people who are identical in all ways except one is highly extraverted while the other is low in extraversion, the individual who is higher in extraversion is likely to just respond to the survey in a rosier manner. That doesn’t actually mean that the extraverted individual has a ‘better’ life in any way. Rather, it’s just a reflection of the fact that these two people have dispositions that lead them to fill out the same survey differently.

In the psychological research literature, the ways in which personality tends to bias subjective well-being assessment are referred to as “top-down” influences. This is in contrast with “bottom-up” influences – i.e., objective life circumstances such as income, health, etc. Researchers initially thought that bottom-up factors would play a greater role in subjective well-being assessment, but top-down factors received increasing attention after initial models of bottom-up factors performed worse than anticipated. In other words, although researchers suspected objective factors from our day-to-day life would strongly predict satisfaction, it turned out that most objective factors were less related to well-being assessment than anticipated (notably, however, there are some factors such as unemployment that are more strongly related to well-being assessment). Today, integrative models that include both bottom-up and top-down factors are considered the best models for predicting happiness, but top-down influences play a very significant role in how people respond to questionnaires.

To give a concrete example of how personality can be a complicating factor if one is trying to make life decisions based on happiness research, consider the relationship between extraversion and urban living. It’s probably not surprising to hear that extraverts tend to enjoy city life more than introverts. Therefore, many extraverts self-select into urban environments whereas introverts may self-select into less urban environments (in fact, introverts have even been found to select into more secluded areas such as mountainous regions).

Now, given that extraverts are temperamentally disposed to give higher answers when asked to rate their happiness on a scale of 1-10, what should we make of the finding that people who live in urban areas are happier than those who live in rural areas?

We cannot actually conclude that people who live in urban areas are truly “happier” (in the broad sense) than those who live in rural areas. It may simply be that personality is confounding the results (and, in fact, the authors of the report referenced above specifically note that The World Gallup Poll does not gather information on personality and therefore they cannot control for personality).

Furthermore, even if extraverts are “happier” (in the broad sense) than introverts when living in the city, it does not follow that introverts would receive the same increase in happiness if they were moved to the city. Rather, it’s quite likely that someone who does not want to live in a city would be less happy if they were forced to relocate to a city.

Accordingly, when thinking about factors that will lead to better lives for individuals, it is very important to consider how one’s own personality aligns with a given factor. “People who live in cities are, on average, happier, therefore anyone would be happier living in a city” is not a logically valid statement. Many extraverts will be happier in cities, whereas many introverts will be less happy in cities. The person-situation fit cannot be ignored. In other words, if a person is not a good fit for a situation – perhaps an extraverted individual trapped alone in the mountains – then that needs to be taken into consideration.

These same considerations regarding person-situation fit extend to all sorts of life decisions. For instance, a PayScale survey conducted from 2013 to 2015 assessed 2.7 million survey respondents and found that “Personal Financial Advisors” ranked 72/502 in terms of career satisfaction. and 215/505 in terms of job meaningfulness. Yet, many financial advisors reading this may think they have the greatest job in the world and may also find tremendous meaning in what they do. It’s doubtful the typical financial advisor would find more satisfaction out of being a mechanical door repairer (despite mechanical door repair ranking 23/502 in terms of satisfaction, much higher than personal financial advisors), but it’s likewise true that the typical mechanical door repairer probably wouldn’t be more satisfied as a financial advisor.

Mismatches between personality traits and life circumstances certainly exist, and if a person finds themselves dissatisfied with their career, then it can be worth exploring what might be a better fit. For the most part, though, people do tend to select into careers that are a pretty good fit for their skills, personality, and interests. Therefore, it would be foolish for someone to ignore what they know about themselves and instead choose a career based on its average level of happiness as reported in a happiness survey. Yet, this is often precisely the case when people naively rely on those happiness surveys for help making important life decisions!

What Should You Rely On To Make Life Decisions?

There are a few general rules we can follow to help make better decisions (or at least avoid bad decisions) when thinking about what will bring meaning to our lives as individuals.

First, it’s important to understand your own personality or temperament and not to ignore those factors when making decisions. Do you prefer red wine to white? Then you probably shouldn’t give two hoots that some groups of people reported greater feelings of happiness when drinking white wine instead of red.

Now, this is not to say that we shouldn’t ever take such findings into consideration. Perhaps one is relatively indifferent between red and white wine but tends to select red out of habit. Maybe it’s worth mixing things up a bit to explore and see what happens.

Changing things up may be particularly warranted when we notice ourselves on a path that wasn’t deliberately chosen. For instance, I’ve recently gained significant satisfaction from strongly cutting back on the number of digital applications that are allowed to send me push notifications. I didn’t rely on any happiness studies to help make that decision, but if I had seen a study that people with a similar background as myself were happier after making the change, then it would have been worth giving the change some thought.

This is particularly true since I never consciously decided that I wanted to have so many applications – email, Slack, social media, etc. – pushing me notifications. I just accepted the default and never gave it any thought. But, upon reflection, I am aware that I thrive on long periods of uninterrupted work. That’s when I genuinely do my best work, and I feel better when I do my best work. I had just ended up in a situation where I was largely oblivious to all of the ways that various applications were interfering with my ability to do my best work.

A second important consideration is to acknowledge that happiness – at least in the narrow sense of how a 10-point scale might define happiness —may not be a proper aim in life. Researchers are doing the best they can to try and measure happiness, but the type of happiness that gets measured and reported in the media is a very shallow form of happiness and should be recognized as such.

Seeking purpose and meaning is a much better aim in life. In Roy Diliberto’s Financial Planning: The Next Step, Diliberto discusses the role of death (or contemplating death) in refining and clarifying what is most important to us:

Many of us know peole who came close to death and completely changed their lives. The near-death experience cuased them to evaluate what was most important in their lives.

Of course, this same insight is largely the motivation for George Kinder's "third question" from his famous series of three questions for having a meaningful discussion about a clients goals and values:

The doctor told you this time [previous questions use different times frames] that you have only one day left in your life. Ask yourself, what am I feeling? What are my regrets and longings? What dreams will be left unfulfilled? What do I wish I had done? What do I wish I had been?

This sort of "deathbed test" helps us prioritize and focus on what is most important. When applying this test in a financial planning context, we'll generally realize that what might have been thought of as a financial goal (e.g., beating the S&P 500), was actually not a good life goal at all. As noted by Diliberto and others, people don't lie on their death beds wishing they'd outperformed the S&P 500 by another percent over the course of their life.

Each person will have their own unique way of evaluating what they should be pursuing and how they can best keep themselves on track, but making a decision just based on what delivers a higher level of ‘narrow happiness’ is almost certainly not what we ought to be doing. To the extent that we’re fine-tuning our choices, perhaps considering such insights might be helpful, but for major choices, narrow happiness should probably play almost no role at all.

It would be a mistake, for instance, to choose not to have children solely due to the finding that suggests parents have lower levels of happiness than similarly aged non-parents. If someone wants to be a parent, then the meaning they get from that role will far outweigh the stress that comes with parenting. This narrow perspective of how research has attempted to define happiness could also be shortsighted, as grandparents tend to be happier than non-grandparents (in his book, Selfish Reasons to Have More Kids, economist Bryan Caplan argues that people should engage in “enlightened family planning” and think about how many kids they would want to have when they reach age 60, because shortsightedness can lead to overweighting the shorter-term stress of children). In these situations, the deep form of happiness that is potentially given up is what is far more important here.

A related word of caution is that when it comes to big life decisions, we may want to give greater weight to various adages and folk wisdom that have faced the greater tests of time – particularly when a contemporary research finding may seem counterintuitive.

A Case Study: Should You Live Near Children In Retirement?

There’s one retirement-related finding that has received a fair amount of press in recent years that works well as a case study for bringing together this full discussion, and highlighting the importance of making choices based on how a person uniquely identifies what “happiness” means to them and what brings them the most personal satisfaction and joy (versus chasing after the purported ideals identified by research surveys that will never apply universally to everyone).

In a 2017 research article, Michael Finke, Nhat Ho, and Sandra Huston found no relationship between retirees living close to children and the retirees' levels of happiness (or, more precisely, no difference in levels of life satisfaction). In the closing remarks of that paper, the authors suggest:

If your clients are anticipating a move to be closer to children/grandchildren in retirement, it might be helpful to guide them through a cost-benefit analysis and realistically assess and manage expectations before any drastic changes are made in this area.

A separate presentation from Michael Finke reports lower levels of retirement satisfaction among retirees who live within 10 miles of their children.

To quote Michael Finke from a Morningstar podcast:

Well, if your rationale for having kids is that they were going to make you happier in retirement, then that doesn't pan out as a hypothesis. Having kids does not necessarily make you happier. Living within 10 miles of your children makes you less happy on average. And I think what happens is, people have expectations about what that relationship is going to be like after retirement that don't necessarily match reality. You may have very positive interactions with your children on an irregular basis. But when you live near them, that completely changes the dynamic of the relationship. Also, there may be the case that both spouses don't agree that living close to a set of children is the right course of action in retirement. There's all sorts of in-law dynamics that go on. You may think that you're going to have a very fulfilling relationship, and then, you end up being a cheap babysitter, and you have all sorts of wonderful advice to provide that is not listened to. Again, it's important to be realistic. But I do think it's also important to be aware of the research. And in this case, the research says that that's probably not the best course of action.

Now, in fairness to Michael Finke, there may be truth in most of what he says. Is it possible for some to be too close to children? Sure. Is it possible to have unrealistic expectations about a relationship? Definitely. Is it possible to wind up in a situation where you feel underappreciated? Absolutely.

And there’s certainly nothing to disagree with when it comes to the suggestion of having realistic expectations and weighing one’s options in a thoughtful manner. There are all sorts of fine-tuning questions at the margins that are worth considering and likely very wise here.

But the importance of thoughtful planning and reflection is not the takeaway from research like this that seems to get people’s attention. What is getting attention – particularly in the media and popular publications – is the surprising claim that living near children in retirement does not lead to greater happiness.

For instance, a blog post at the CFA Institute reports:

Living within 10 miles of your kids is not a good idea – apparently you may be unhappier in retirement because of it. If your plan for retirement is to move closer to your children, it tends not to work out very well.

Similarly, an article at CNBC reports:

Retirees who live less than 10 minutes from their kids are ultimately less satisfied.

And an article at Parade notes:

For example, happiness isn’t always increased by living extravagantly or by being close to your kids. “There’s zero evidence that those who live near their children are happier,” says Michael Finke, who studies retirement and happiness.

Robert Powell at TheStreet reports:

There is no evidence, however, to support children contributing to retiree life satisfaction. Given that, the authors suggest that you might want to think twice before selling your home and moving closer to your children/grandchildren.

An author at Business Insider reports:

Surprisingly, the researchers found "no evidence to support children contributing to retirees life satisfaction," although having close relationships with friends and, to a lesser extent, other family members does.

I have to admit I did a double-take on this assertion about children, as it seems inconsistent with the importance most parents place on their relationships with their kids.

I could go on and on, but I think you get the point.

There are a few things to note about these findings.

First, even if we accept narrow happiness as a worthy end in and of itself, the relationships in question here (or lack thereof) are minuscule. The chart from Finke’s presentation, shown below, reports a reduction in retirement satisfaction of -0.02 for those who live less than 10 miles from their children. The measure used within the Health and Retirement Study is a 3-point scale with response options of “very satisfied” (3), “moderately satisfied” (2), and “not at all satisfied (1). So an average reduction of -0.02 is not that big of a difference.

Furthermore, the regression coefficient in the Finke, Ho, and Huston paper for close relationships with children is actually positive (0.007) rather than negative, although the relationship is not statistically significant.

Granted, it’s reasonable to counter that even a lack of a relationship is notable given that most people would likely suspect the relationship to be positive, but let’s be real about the relationship here: Even if we were to accept this narrow form of happiness as a reasonable aim in life, should someone who really wants to live by their children (and possibly grandchildren) actually be holding off on doing that because the average retiree reports a -0.02 reduction in retirement satisfaction on a 3-point scale? I don’t think so.

First, there are a number of limitations that ought to be considered. For instance, top-down influences (like personality) on subjective wellbeing assessment – which, recall, are generally the strongest predictors of subjective wellbeing assessment – are not controlled for in any way. Differences in personality or similar factors could be confounding relationships in this particular finding of the relationship between retirement satisfaction and living near children in retirement.

Additionally, while it’s possible that retirees are moving closer to their children, another potential confounder here could be that, in some cases, it’s children who are moving closer to retirees because of health or other concerns that don’t show up in the health variables that were controlled for. The point here isn’t to be overly nit-picky – the list of potential limitations for any research study is endless, and anyone can criticize any analysis after the fact – but the limitations here aren’t trivial and that should particularly temper any strong conclusions one might make from small relationships.

But even more importantly – as noted by McCloskey, Peterson, and others – this shallow form of happiness should not be treated as a proper aim in life.

Is it terribly surprising that a retiree who spent an afternoon playing golf might answer a happiness survey slightly more favorably than one that just spent an afternoon babysitting a toddler?

Probably not. But the two are potentially very different when it comes to feeling a sense of purpose and meaning. To apply a sort of the "deathbed test" that aligns with Kinder's questions and Roy Diliberto's teachings, few people lie on their death bed wishing they’d gotten a few more rounds of golf in. However, many do lie on their deathbed wishing that they’d formed better relationships with family.

Parents know the feeling of watching children grow up so fast and wondering how the time slipped away. And, of course, grandparents typically feel the same.

Granted, this is certainly not to suggest that the right choice for everyone is to be closer to family. There may be very good reasons for someone to desire not to be close to family. The point here is that the information one has about their own circumstances – their desires, relationship dynamics, etc. – will likely prove much more valuable for an individual in choosing a course of action that will bring the most happiness to them, rather than basing their decision on average responses to a survey question.

This goes back to person-situation fit. Just because the extraverts surveyed were generally happier in the city does not mean that introverts would be if they were forced to move out of the mountains.

And while Finke and his coauthors are right to suggest that some thoughtful deliberation should precede any major life change like a relocation, some of that deliberation could also be on how to approach a relocation closer to family that will provide a better outcome for everyone involved.

What are everyone’s preferences (children and parents) in terms of ideal distance? How often does everyone expect to interact with one another? What boundaries need to be in place to keep everyone happy?

In addition to his thoughts on “enlightened family planning” mentioned above, Bryan Caplan’s book has a section devoted to becoming the “in-laws from heaven”. For instance, Caplan suggests that grandparents shouldn’t “bundle your babysitting or other assistance with unwanted advice about how to raise your grandchildren or run the household.” Caplan’s rule of thumb to know if advice is wanted: “If someone wants your advice, they will ask for it.”

Finke notes that some grandparents may be frustrated that their advice isn’t listened to – and he may certainly be right – but perhaps the better adjustment to make on the front-end is to realize that almost no one ever wants unsolicited advice. Grandparents that follow that advice may find that relationships are better and less stressful.

But the main point here is that the deliberation on the front-end doesn’t have to be just whether one moves or not. Assuming parents do want to be closer to their children, the focus can instead be on how to make being close work as best as possible, as being closer to their children can provide a valuable sense of meaning, purpose, and significance.

Because, ultimately, discouraging the pursuit of meaning and purpose – even when it may come with some additional forms of stress – is generally not going to be what promotes a deeper, richer sense of living a good life. And when we see happiness research findings that seem to fly in the face of conventional wisdom, we should be particularly careful in using that information to guide life decisions. In many cases, the “calculative hedonics of 1-2-3” are simply not the aim we should use for setting life goals.

While we may have different opinions on financial planning/planners, I have nothing but praise on your article.

I thought it was a great, insightful read and should be utilized by many in the review of client questionnaires that, supposedly, determine risk as well as the attempt to design same through various (and unique) human behaviors.

All planners et al should read this to gauge the accuracy of simplistic methods in defining clients who are always different- yet continue to put them into cookie cutter analyses.

KUDOS TO YOU

Thanks for sharing this informative article.

Best Legal Service platform in Bangladesh.

That settles it. I plan to live within 10 miles of my golf club when I retire.

Any chance we can get the same article without the Jordan Peterson quotes? Prof Peterson is a demonstrated opponent of inclusivity. You can find pretty much the same quotes about happiness from Laurie Santos or Liz Dunn, for example.

But yes, very good article.

Awesome Blog! Very informative! Thanks for sharing.