Executive Summary

Over the past year, a series of revelations about the CFP Board's compensation disclosure requirements have significantly shifted the landscape in how CFP certificants must explain their compensation to prospective and current clients. While the CFP Board maintains that "nothing has changed" since the rules were formally enacted over 5 years ago, the fact that large numbers of advisors continued to find themselves out of compliance - with another potential shoe soon to drop - suggests that whether the organization admits it or not, the CFP Board has changed the rules of the game.

In fact, the CFP Board's current framework is so expansive in the compensation that must potentially be included, that virtually all advisors in today's environment end out being in one broad bucket labeled "commission and fee", which groups together not only advisors who earn 1% in commissions with those who earn 99% of income in commissions (despite the clear difference in actual business model!), but even renders "commission-only" advisors who earn 100% commission income as "commission and fee" because they work for a firm that "could" generate a fee (along with requiring a number of advisors who earn 100% of income as fees to declare themselves "commission and fee" if they "could" earn a commission as well). The end result: when nearly all advisors must use the same compensation disclosure label of "commission and fee" to define a wide range of actual compensation structures from 0% commissions to 100% commissions, the very purpose of compensation disclosure begins to lose its meaning, value, and clarity for the public that the CFP Board purports to serve.

While the CFP Board maintains that it cannot "fix" or change its rules without a long drawn-out rulemaking process, arguably the reality is that it already changed its rules without such a process to reach the point we're at now. In addition, the fact that the CFP Board eliminated its own "salary" compensation category just over 6 months ago, makes it clear that when it comes to interpreting and adjusting its own definitions, the CFP Board does have latitude to fix its own mistakes. Yet, mysteriously, the CFP Board has yet to be held accountable for the problematic definitions it is now using. With CFP certificant stakeholders reporting behind-the-scenes that they are afraid to speak out for fear of retribution (justified or not), and the FPA and NAPFA apparently abdicating their advocacy roles on behalf of members to take a back seat to the CFP Board, it remains unclear what will finally push the issue. Will someone have to file complaints against a thousand CFP certificants in violation of the CFP Board's own problematic rules, effectively "throwing those CFP certificants under the bus", just to force the CFP Board to pay attention? Will its Board of Directors finally take a more active accountability role to intervene and preserve the enforcement integrity of the organization?

Compensation Disclosure Requirements For CFP Certificants

Under the CFP Board's Rules Of Conduct, CFP certificants are required to disclose compensation to prospective and current clients. The key rules include that the certificant shall provide/disclose:

Rule 1.2(b): Compensation that any party to the agreement or any legal affiliate to a party to the agreement will or could receive under the terms of the agreement; and factors or terms that determine costs, how decisions benefit the certificant and the relative benefit to the certificant.

Rule 2.2(a): An accurate and understandable description of the compensation arrangements being offered. This description must include:

- Information related to costs and compensation to the certificant and/or the certificant’s employer, and

- Terms under which the certificant and/or the certificant’s employer may receive any other sources of compensation, and if so, what the sources of these payments are and on what they are based.

For the purpose of these rules, the key term "compensation" is defined under the "Terminology" section of the CFP Board's Standards of Professional Conduct as:

“Compensation” is any non-trivial economic benefit, whether monetary or non-monetary, that a certificant or related party receives or is entitled to receive for providing professional activities.

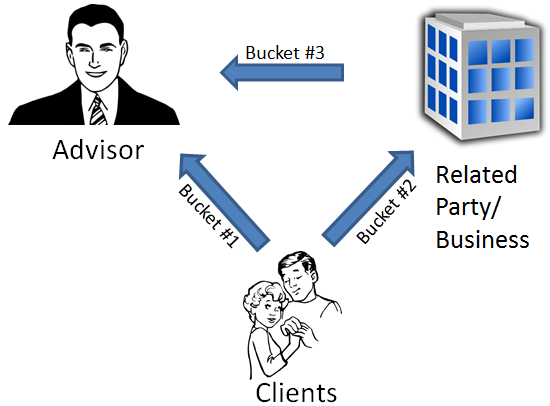

Within this framework, advisors are expected to disclose that they work either on a "fee-only", "commission-only", or "commission and fee" basis, depending on what compensation they receive, or are entitled to receive, from one of three "buckets" as shown below. If each of the three buckets are only capable of paying fees, the advisor may call themselves fee-only. If the buckets are only capable of paying commissions, the advisor is commission-only. In all other cases, the advisor is commission-and-fee.

CFP Board Problematic Application Of Compensation Disclosure Rules

While the above set of rules for disclosing compensation would seem relatively straightforward, the CFP Board's application of the rules in recent years has created a tremendous amount of confusion. The starting point was the CFP Board's sanctioning of former Board Chair Alan Goldfarb, who had stated that he was "fee only" because, logically, all of his clients only paid fees (to him or his company) for services. However, because Goldfarb's RIA was owned by an accounting firm, that also owned a broker-dealer (used primarily to facilitate small business merger transactions), and because Goldfarb himself owned a 1% interest in the broker-dealer, the CFP Board declared that Goldfarb should have declared himself "commission and fee" because he could indirectly receive a commission under bucket #3 above... regardless of whether any client was doing business, had ever done business, or was ever intended to do business with the broker-dealer in the first place. In other words, even being able to prove that 100% of clients only paid 100% of compensation via fees was not a sufficient defense to claiming "fee-only" status, because the mere presence of an entity in which Goldfarb and/or his employer owned a small interest, and which "could" generate commission compensation that "could" be paid, was sufficient to taint the fee-only claim (regardless of whether a commission ever actually occurred or not!).

After the CFP certificant community signaled confusion and concern about this ruling, the CFP Board followed up with a Compensation Disclosure Webinar on August 7th, and released an important "Notice to CFP Professionals" regarding accurate compensation disclosure, where it further extended this novel approach to compensation disclosure by declaring that any employment relationship with an entity that can generate commissions for any advisor will taint the fee-only status for all advisors, even if the advisor has never actually done any commissions and never intends to do so. In fact, any common ownership of a commission-related entity by the CFP certificant's employer could taint "fee-only" status, even if no client even does business or is intended to do business with the entity, as was the case with Goldfarb.

The problem with this approach is that it divorces "what clients actually pay" from what advisors must disclose as compensation, even though the whole point of compensation disclosure is to explain to clients how they will be compensating their advisor! In a world where any affiliation (employment, miniscule ownership, common ownership from an employer's holding company, etc.) to an entity that can collect commissions taints the "fee-only" label, very few advisors are left being able to call themselves fee-only. Any advisor who is employed by a broker-dealer - even if exclusively charging clients fees, and even if exclusively working for the company's fee-only RIA - cannot describe themselves as fee-only. Nor can any advisor who invests any portion of their personal net worth in a commission-paying entity (remember, Goldfarb was deemed "commission and fee" in part because he owned a 1% interest in a tiny broker-dealer that paid him less than $2,000 in dividends, a payment that's smaller than what many advisors receive as a dividend from broker-dealers in their S&P 500 index fund!), even if no client does business with the entity. Even advisors working for large RIAs that are partially bought by banks or holding companies lose the right to call themselves fee-only, because banks generate commissions on mortgage products (a problem even if the advisor never refers clients to the bank for any mortgage solutions) and virtually every holding company owns an interest in some broker-dealer or bank somewhere in its portfolio of holdings (e.g., even Fiduciary Network is owned by Howard Milstein's Emigrant Bank, which also owns two bank/mortgage companies in New York, apparently rendering many of Fiduciary Network's large prominent fee-only RIAs as being in violation of the "fee-only" disclosure rules).

And unfortunately, the problems extend further than just "fee-only" compensation disclosures. Given that just having any form of affiliation to a commission-paying entity is enough to taint the "fee-only" compensation disclosure for advisors, it would similarly be true that having any form of affiliation to an entity that could charge a fee would taint the "commission-only" compensation disclosure, as first pointed out previously on this blog. And given that virtually every broker-dealer and insurance company is at least capable of charging a client a fee for something - even if it's one-time standalone advice - this is turn means that just as every wirehouse broker who claimed they were "fee-only" was in violation of the rules because their company could generate a commission, so too is every "commission-only" advisor at a broker-dealer or insurance company in violation of the rules because their company could generate a fee! Given that the CFP Board continues to maintain that it is "compensation neutral" and that it treats all compensation models equivalently, it would seem that its failure to enforce its own rules against "commission-only" advisors is just the next shoe to drop, just as it was already publicly embarrassed for failing to enforce its rules against wirehouse advisors who claimed they were "fee-only" but weren't allowed to use the term under the CFP Board's interpretation of its rules after the issue was first raised on this blog. Ultimately, it's not clear that any advisor has, by virtue of real world employment relationships, a business where it would actually be legitimate to call themselves "commission-only" - such that the definition may have been rendered entirely irrelevant, just as the "salary" definition was too!

We're (Almost) All Commission-And-Fee Now?

To illustrate the sheer ridiculousness of how the CFP Board's overly expansive interpretation of its own rules is creating problems for advisor compensation disclosure and a lack of clarity for consumers, imagine a prospective financial planning client who goes to interview 6 different prospective CFP certificant advisors, and reviews their compensation disclosures as a part of the prospective relationship:

- Advisor works for major insurance firm, offering financial plans for free and selling life insurance for 100% of his (commission) compensation. However, because the insurance company has advisors who could provide a financial plan to clients for a fee (regardless of whether this one does), the advisor must also disclose fee compensation. As a result, even though the advisor works exclusively on a commission basis, always has, and always intends to, his compensation disclosure is "commission and fee."

- Advisor works for wirehouse, selling certain proprietary investment solutions on a commission basis. However, the advisor can refer clients to the firm's financial planning department, to which clients pay a fee, and for which the advisor receives a bonus based on financial planning fees paid. Last year the advisor referred one client to the program, and as a result her compensation was 99% commissions and 1% fee. Advisor's proper compensation disclosure is "commission and fee."

- Advisor works for an independent broker-dealer, regularly providing financial plans for a fee, and implementing the solutions on a commission basis. Last year, the advisor's compensation was fairly evenly split 50%/50% between commissions and fees. Advisor's compensation disclosure is "commission and fee."

- Advisor works for an independent RIA, but also has an insurance arrangement with a local general agency to receive a revenue share of commissions when younger Gen X and Y clients implement necessary term insurance. Last year, the insurance commissions amounted to less than 1% of the advisor's revenue, and the remaining 99% was comprised entirely of fees. Advisor must disclose her compensation as "commission and fee."

- Advisor works for a large, established RIA, that operates exclusively on a fee basis with clients. However, the firm's founding partners sold a minority interest in the firm to a large national bank, which also offers (unrelated) mortgage lending services (for which mortgage brokers are compensated on a commission basis). Even though 100% of the firm's compensation is from fees (and always has been), and they have never referred any clients back to the bank (and never intend to), because the firm's ownership includes a bank that also owns a commission-paying entity, all of the RIA's advisors must disclose their compensation as "commission and fee."

- Advisor is self-employed under a small state-registered RIA, providing financial plans for a fee and charging for assets under management. Because the advisor's compensation is 100% fees, and the advisor has no financial interest in any other businesses that generate commissions, and no portion of the advisor's firm is owned by another person or entity that also has a financial interest in any other businesses that generate commissions, the advisor can disclose their compensation as "fee-only."

The above scenarios highlight how ineffective the CFP Board's currently compensation disclosure rules are at actually providing clarity for consumers, which ostensibly is the whole purpose of compensation disclosure. None of the advisors can include the "commission-only" compensation disclosure, even the advisor who does generate 100% of his income from commissions, and must instead disclose "commission and fee" instead (scenario #1). Some of the advisors who generate 100% of their compensation from fees must declare themselves "commission and fee" as well (scenario #5). Advisors who generate 1%, 50%, and 99% of their income from commissions (with the large-or-small remainder from fees) must all disclose "commission and fee" as well.

Yet of course, the reality is that there's an incredible range of actual compensation and business arrangements characterized by the 6 scenarios above. The fact that the CFP Board's current compensation disclosure rules puts 5-out-of-6 into the same category - including advisors that range from actual compensation of 0% commissions and 100% commissions - highlights how useless compensation disclosure has become in disclosing actual compensation and its associated conflicts of interest to clients. At least if advisors disclosed what clients actually pay, scenario #1 would be commission-only, scenarios #5 and #6 would be fee-only, and only the middle three would fall into the same "commission and fee" bucket. Although arguably, even that is of limited effectiveness; are we really trying to suggest that consumers are best served with a compensation disclosure framework that states it's more important to distinguish between 100% commissions and 99% commissions (commission-only versus commission-and-fee) than to distinguish between 99% commissions and 1% commissions (both commission-and-fee)? Why is it SO important to clarify the difference between 100% and 99% commissions, but it's OK to lump together 99% commissions and 1% commissions?

And sadly, even these 100%/99%/1% distinctions are more effective than the actual current state of affairs, where the CFP Board would require 5-out-of-6 to use the exact same compensation disclosure of "commission-and-fee" and reserves "fee-only" for only a tiny subset of small RIAs that are still entirely independently-owned and haven't been around long enough - or grown large enough - for their founders to sell to a larger entity that might also have ownership, somewhere in its holding company structure, of an otherwise-unrelated-to-clients entity that could, possibly, someday, somehow, generate a commission (even though there's no intention to ever do so).

Where Do We Go From Here?

Perhaps the first step to a solution is simply to acknowledge that there's a problem... which the CFP Board has thus far refused to do. While CFP Board CEO Kevin Keller maintains that the organization is "fully engaged" on the issue, the organization has also not taken a single overt action step in nearly 6 months now, beyond the dissemination of its Notice To CFP Professionals and its webinar on compensation disclosure. The organization has not otherwise even publicly acknowledged that anything needs to be changed, much less opened up a process about how to do so; even a rumored FAQ (Frequently Asked Questions) document that would have provided clarification on a number of murky issues has failed to materialize.

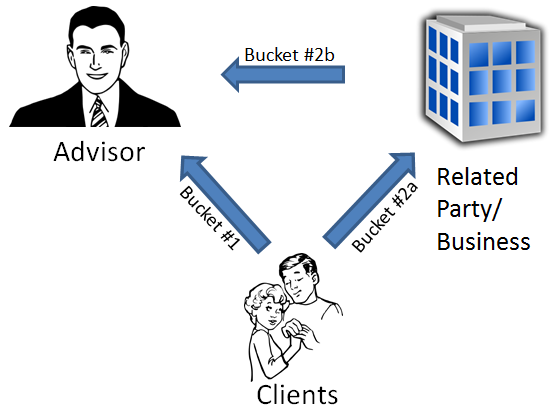

A previous article on this blog suggested at least one way out, where the CFP Board could refine its interpretation of its own 3-bucket rule to recognize that compensation disclosure is about what a client actually pays to the advisor, or to the advisor's employer or other related party, and that payments from a related party back to an advisor should only count if they are ultimately sourced from the client (and only if they actually exist in the first place!). Accordingly, the 3 bucket" approach to compensation disclosure would become a "2 bucket" approach, where the bucket to related parties has two sub-parts: a) was something paid by the client to the related party; and b) was a payment then made from the related party back to the advisor, such that the advisor was receiving indirect compensation, as shown in the graphic below. Such an approach would appropriately acknowledge, per scenarios #1 and #5 earlier, that an advisor can still be "commission-only" or "fee-only" even if the employer has OTHER ways to do business that may involved other forms of compensation, as long as the actual advisor and his/her clients have never actually paid the other type of compensation, directly or indirectly, to the advisor (and don't intend or hold out that they plan to do so).

Sadly, the response from the CFP Board so far has been that its compensation definition rules "can only be changed by an elaborate process of proposal, notice, comment and subsequent adoption by the board." Of course, this explanation completely ignores the fact that just last August, the CFP Board staff unilaterally chose to alter the compensation disclosure definitions by eliminating the "salary" category from its website, after it was pointed out on this blog that "salary" is an invalid compensation disclosure, as it's a way that firms pay advisors, and not a way that clients pay advisors; i.e., even a salary paid to an advisor is ultimately funded by either a fee or a commission (or both) paid by the client to the advisor's firm, so the proper client-centric compensation disclosure would still be "fee-only", "commission-only", or "commission and fee" instead.

In fact, when the CFP Board eliminates its salary compensation disclosure, it did so with the specific explanation "...salary does not provide an accurate and understandable description of the compensation arrangement being offered by a CFP® professional because it does not describe how the client will pay the CFP professional and any related party." (emphasis mine) So if the CFP Board has the power, now, to eliminate the "salary" compensation category altogether, and declares that compensation disclosure should be based on "how the client will pay the CFP professional and any related party" (not just how a firm compensates the advisor in the absence of what the client actually pays), then why can't the CFP Board apply the same clarifications of their problematic interpretation of the "3 bucket" approach? In other words, when it came to removing "salary" from the definitions, the CFP Board showed that it has the power to do so and the definition was all about "how the client will pay the CFP professional and any related party", but when it comes to defining "fee-only" or "commission-only" that same interpretation no longer applies and the CFP Board staff suddenly declares it is powerless to fix the problem? At this point, it's not entirely clear whether the CFP Board staff doesn't even realize it is inconsistently interpreting its own rules, is misinterpreting its own powers to fix them, or are deliberately stonewalling to avoid a public perception of backtracking in the midst of a lawsuit, but the longer the situation goes unremedied, the more the CFP Board's brand is potentially damaged.

Even beyond fixing the CFP Board's currently problematic and erroneous interpretation of its own "3 buckets" rule - which distorts scenarios #1 and #5 discussed earlier, and has made "commission-only" a logically impossible compensation disclosure given the realities of how financial services companies are structured today - the problem still remains that scenarios #2, #3, and #4 are all in the same "commission and fee" bucket, despite the fact they range from advisors earning 1% in commission income to 99% in commission income. This suggests that even beyond just fixing the three-bucket methodology of its definitions of "fee-only" and "commission-only" the CFP Board also needs to consider better refinements to its "commission and fee" label (though admittedly, this almost certainly would require a broader discussion with CFP certificants and other stakeholders to refine the rules further). As a starting point, perhaps we could at least make a distinction between "commission and fee" versus "fee and commission" based on which contributes the greater-than-50% share of the advisor's actual income for services rendered?

In the meantime, though, it remains to be seen what will break this apparent stalemate. The CFP Board does not seem to feel it is beholden to the CFP certificant stakeholders who have complained and objected to this rule, including their former chair Alan Goldfarb who was publicly admonished for violating the very rules he reported participated in writing in the first place (perhaps the clearest evidence that the CFP Board is not applying the rules in the way they were originally intended). While the CFP certificant community has not complained en masse about the issue, many have contacted me directly about the issue stating that they're afraid to take public positions for fear of retribution, as they perceive the CFP Board's rulings thus far - and its rollercoaster of public admonitions and widespread amnesties - to be arbitrary and capricious and creating uncertainty about the consequences of public criticism; while I will admit that personally I think this fear is overstated, it does raise the point that the CFP Board may be creating an environment where stakeholders are afraid to voice concerns publicly because of its own enforcement policies, and then appears to be taking their silence as acquiescence to the current rules instead of fear of criticizing them?

Sadly, the membership organizations are capable of arising above this level of the fray, but both the FPA and NAPFA have continued to be remarkably "hands-off" in pushing the CFP Board to action; while each organization has stated a need to address the compensation disclosure definitions, both have indicated that they will wait for the CFP Board to make the first move, despite the fact that the CFP Board has not publicly acknowledged it even believes a change needs to occur and that there is no first move forthcoming (and in fact, last fall declared that the problem is not about CFP Board changing at all, but about NAPFA and the FPA changing their definitions to comply with the CFP Board!). NAPFA's silence is especially surprising, given its 30-year leadership in pioneering the definition of "fee-only" and the fact that approximately 5% of its own members are in violation of the CFP Board's rules (although the NAPFA members are not in violation of NAPFA's own standards, NAPFA does require its NAPFA-Registered Financial Advisors to be CFP certificants, which in turn would require them to honor the CFP Board's Standards of Professional Conduct regarding compensation disclosure and not declare they are "fee-only" in violation of CFP Boards). In turn, NAPFA's apparent refusal to take an active and public role in the process and delegate the decision to the CFP Board of when/whether to act at all raises the question of whether NAPFA has abdicated its leadership role in compensation definitions, which would represent a serious shift in how the CFP Board is held accountable.

Of course, one way to "force" this issue - where the CFP Board insists it is not accountable for widespread violations of its own rules until/unless a complaint is filed - would simply be to file complaints against hundreds or a few thousand CFP certificants... for instance, every advisor who is commission-only, all advisors at RIAs that are owned by a parent company, etc., to compel the CFP Board to acknowledge the issue and address it. Unfortunately, such a path also threatens to pressure the CFP Board's resources from "legitimate" violations it should be addressing, would be a public relations humiliation for the organization, and needlessly throws "innocent" advisors under the bus who would be named in the complaints. It would be a sad resolution to the issue if the CFP Board feels this is the only way it can/should be held accountable for its own rule ambiguities.

Perhaps, ultimately, it will be the Board of Directors of the CFP Board itself that decides to apply the pressure to clarify the rules, especially given that the CFP Board remains embedded in the midst of its litigation with Jeffrey and Kimberly Camarda regarding compensation disclosure... a case the CFP Board can ill afford to lose on the back of its ongoing inconsistencies and ambiguities in its compensation disclosure rules, from striking the salary definition while insisting it cannot clarify the fee-only definition, to continuing to operate with a commission-only definition that technically every commission-only advisor is currently violating, to publicly sanctioning Alan Goldfarb - and trying to do the same to the Camardas - even while granting amnesty to wirehouse brokers who had been violating the same rules.

If the CFP Board wants to ultimately be the long-term enforcer of financial planning on behalf of the profession, and to uphold its mission of benefiting the public by upholding the CFP marks as the recognized standard of excellence for competent and ethical personal financial planning, perhaps it's time to step up and take responsibility for its problematic definitions and inconsistent application of its rules that have rendered compensation disclosure meaningless for consumers... and if it won't, its Board of Directors needs to compel it to do so, for the sake of the long-run credibility of the organization and its marks.

Michael,

Thank you for continuing to beat this drum, in your usual well-reasoned fashion!

I’m

one of those advisors who is currently about 99% fee and 1% commission

(insurance), so I simply “sidestep” any compensation pigeon-hole in the

CFP Board listing, FPA directory, etc. I just don’t bother answering the

question. “Commission and fee” is an inappropriate description for my

practice, at least in the way any normal thinking person would

understand that phrase.

I’ve become so thoroughly disgusted with

the CFP Board’s idiocy over this matter–and its treatment of Goldfarb

et al–that I’m wondering whether the CFP Board is actually worthy of my

continuing certification. Surely there must be a lot of others wondering the same.

Keep up the great work!

Larry McClanahan, CFP®, CASL, CLU

SecondHalf Planning & Investment, LLC

Larry,

Unfortunately, I really don’t see a ‘viable alternative’ to CFP certification for setting a minimum professional standard – which ironically is actually why I’m so vocal and critical of the CFP Board’s policies. Because I truly believe it “matters” for them to get it right, and I fear that we would just set our path to profession back significantly by trying to redirect to another standard-setting certification.

But you’re definitely not the only one asking the question about whether CFP certification is still “worth it”. I’m hearing the concern more often as well. I really do NOT think it is time, at all, to abandon the CFP marks. But I do think it’s important to continue to ‘beat the drum’ on the importance of getting these CFP Board issues fixed, and to keep advancing the profession (and the marks) forward.

– Michael

I have a question for Larry and Michael on this.

Larry, in your case, despite the large disparity of 99% fee/1% commission, among the categories of “Fee-Only”, “Commission-Only” and “Fee and Commission”, the third seems to be the correct answer.

So, my question to both of you: if the current compensation disclosure rules are inadequate, how should Larry be categorized? Certainly not “fee-only” right? Are you suggesting that there should be more categories? Such as “mostly fee, and some commission” or “all commission, but allowed to receive fees”

Eric Toya

Great article, Michael. I have to admit I wasn’t aware of just how ridiculous this situation is. Are you kidding me?! This should clearly be about helping consumers understand how they can expect to compensate advisors. This should be a public service which helps consumers make that first filter to help them distinguish an advisor’s primary form of compensation. Why? Because that’s an important consideration when choosing an advisor and the board should help consumers distinguish.

I agree that this renders the compensation definition useless. I’m embarrassed that this is the board representing my professional credential (of which I’m very proud.) Shame on them. As much as they might like to characterize this as a complicated issue, c’mon – it’s not that complicated.

Thanks for bringing this important issue to my attention. I’m outraged.

Colin

I think that you miss an important point. It is not about how the “consumer” or “client” is actually compensating the planner, but the sources of income which the firm receives or could. If my firm charges you a fee, and only a fee for the service, you may think that I am fee only. If we charge a commission to the next person, they may think we are commission only . It is the holistic look which is important.

Good to see continued focus on the Board’s inaction. I have little faith in the CFBOD… Nancy Kistner, perhaps the worst Chair in quite some time, completely punted in explaining or rectifying the inexplicable disparate treatment of amnesty for thousands of CFPs clearly breaking the rules while not affording the same courtesy to Alan Goldfarb et al. Ray Ferrara goes on record out of the gate saying the comp rules are simple, clear and don’t need changing. Kevin Keller has been caught in un-truths by existing DEC commissioner public statements (We had no idea these people were breaking the rules….while DEC commissioners had been complaining for years about these very rule breakers….) Nothing will happen while the Camarda case in pending. Its simple, Kevin Keller and Michael Shaw must resign. They have and are jeopardizing the marks with their keystone cops routine.

Michael

I am not certain that having the term fee-only available solely to firms which legitimately are fee-only is such a bad idea. In my opinion, part of the issue has been that for too long, the press has been feeding the public an incorrect definition of fee-only. I truly do not see how ownership in a non- publicly traded firm that generates commission income can still allow you to be fee only. Only does have a special unique quality associated with it.

If firms have chosen to place themselves in a situation where they have multiple streams of income, and those are commission and fees, then let them simply state that they are commission and fees.

Why should the CFP Board change the definition? However, I do agree with your assessment that the board may be handling the issue in an abysmal fashion. There current TV ads are at odds with the actions of the organization – you cannot state that the people who pay for the license are thoroughly vetted if their is not ongoing audits.

As far as compensation disclosures to the consumer is concerned, the form ADV part II should be the governing document – and the one under which consumers should seek remedy.

Michael,

I noted with interest the part of your article that accuses NAPFA of abdicating on this issue. I would go further and ask if there is some collusion between NAPFA and the CFP Board? Given NAPFA’s decision to limit its membership to planners who have earned the CFP mark, my suspicions were aroused that there have been political quid pro quos at play. Maybe I’m totally off base, but you know what they say about something that quacks like a duck and walks like a duck.

Joel,

I see no collusion there, and no belief there is any. Frankly, this has left NAPFA in the lurch as well. By their own admission, approximately 5% of their OWN members are disqualified from fee-only under CFP Board’s definition. Having NAPFA “fee-only” members disqualified from being fee-only CFPs is NOT something NAPFA would have aspired/colluded to, putting it mildly! 😉

– Michael

Michael,

I very much appreciate your focus on the issue as it does, indeed, seem that no one else of stature is willing to do so. What is most disturbing about the CFP Board’s stand on this issue is the almost FINRAesque (definitely not intended as a compliment) emphasis on the nitpicking application of their rules, rather than on the principles of not misleading clients and the full and fair disclosure of conflicts of interest. The truth ought to be at least relevant and merely technical rule violations ought to be seen for what they are — merely technical rule violations and responded to accordingly.

By assigning a higher priority to their rules than to the broader principles that are the foundation of the profession, the CFP Board is undermining their own standards and the profession we are all striving to build.

David Mendels, CFP®

Creative Financial Concepts, LLC

Michael,

Thank you for posting this. I hope it helps other CFP certificants to become aware of the magnitude of this problem. I agree there is no viable alternative to the CFP designation. I am very active in the FPA and it frustrates me that they are doing nothing about this. I thought our goal was to differentiate ourselves from wirehouse brokers…to be a true profession… and it seems the CFP Board, FPA and NAPFA are not looking out for our best interests. I am hopeful that with more awareness, this will change.