Executive Summary

Since as early as 1960, our national health expenditures have been steadily increasing. The American Medical Association found Americans paid nearly $3.5 trillion on healthcare in 2017, and expenses continue to rise, with estimated increases in healthcare expenses by the Bureau of Labor Statistics pegged at over 7% since 2016.

To address our country's rising healthcare expenses, the Medicare Modernization Act was signed into law by President George W. Bush in December, 2003. This law created Health Savings Accounts (HSAs) to encourage individuals to enroll in High-Deductible Health Plans (HDHPs) in an effort to curb overall healthcare spending. In essence, HDHPs incentivize individuals to make healthcare decisions more carefully, with higher out-of-pocket requirements and lower premium expenses (which can often make up for the higher out-of-pocket requirements – especially for healthy individuals!).

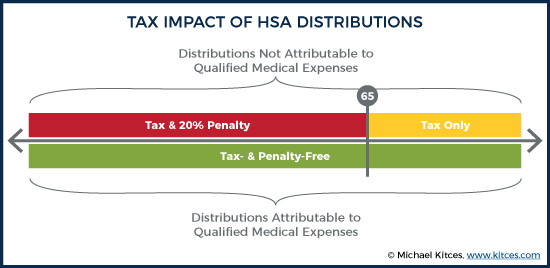

Health Savings Accounts (HSAs) offer a further incentive for HDHP enrollment, as they provide a very attractive 'triple-tax' set of potential benefits. The three potential benefits are: 1) tax-deductible contributions, 2) tax-deferred growth, and 3) tax-free withdrawals for qualified medical expenses (although withdrawals made for non-qualified expenses are not tax-free and incur a 20% penalty if made before age 65). After age 65, though, non-qualified withdrawals have no penalty, so the account virtually becomes an “enhanced” IRA which can be used for any purpose but without the requirement of taking annual RMDs.

As with other tax-preferenced savings accounts, there are contribution limits for HSAs, which are based on the type of HDHP coverage an account owner has. For family HDHPs, annual limits are $7,000 for 2019 ($7,100 for 2020), and for self-only HDHPs, limits are $3,500 for 2019 ($3,550 for 2020). Additionally, HSA owners age 55 and older are allowed to make an annual $1,000 catch-up contribution.

Financial advisors with clients who are married and have mixed health insurance coverage can help their clients understand their actual HSA contribution limits, as these limits depend on the type of plan each spouse has. For spouses covered by separate self-only HDHP plans, each can contribute up to the maximum, self-only limit to their respective HSAs, but they can’t make up for any contribution shortfalls of the other spouse.

Sometimes, one spouse might have self-only HDHP coverage and the other an "employee-and-children" family HDHP (which does not offer coverage for the employee's spouse). This can be cost-effective for couples with children, as family HDHPs sometime provide for “employee and children” coverage that is less expensive than family plans that include both spouses. In this situation, the spouse with self-only coverage is limited to the self-only HSA contribution amount, and the spouse with family coverage can contribute up to the family limit. But while the total between spouses cannot exceed the family limit, the spouse with the family plan can make up for any contribution shortfall of the spouse with self-only coverage.

In rare cases, both spouses may each opt for separate HSA-eligible family HDHPs through their employers (perhaps because of different in-network doctors offered by each plan). Again, the total contribution between spouses may not exceed the annual family limit, but in this situation, both spouses have the ability to compensate for any contribution shortfalls of the other, or to simply choose which spouse's HSA it makes sense to fund first.

Financial advisors who have married clients with HSAs, where at least one spouse is under age 65, can employ some strategies to maximize the value of their clients’ accounts. For example, it may behoove the couple to maximize contributions to the older spouse’s account first in order to reduce the potential exposure to the 20% penalty for non-qualified withdrawals, since the penalty will not apply to the age 65+ older spouse. In addition, using HSA funds from the younger spouse’s account to pay for qualified medical expenses will also result in more funds in the older spouse’s account, available for penalty-free withdrawals for non-qualified expenses.

Ultimately, the key point is that the unique triple-tax benefits of HSAs make them attractive savings vehicles that can be used for expenses beyond medical care (but penalty-free for non-qualified expenses only after age 65). Financial advisors can help their clients with different HDHP coverage options get the most value out of their HSAs by guiding them through their specific contribution rules and choosing how to coordinate withdrawals for qualified and non-qualified expenses from each account in the most tax-efficient manner.

Last year, Americans spent $3.65 trillion on healthcare, with the United States representing the country with the highest total health spending per capita in a recent survey conducted by the Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development (OECD). As such, one of the major planning concerns for many individuals is the mitigation and management of health-related expenses by selecting health insurance coverage from an available set of options that best provides for the individual’s unique set of needs.

In many cases, individuals may opt to pay higher premiums for robust insurance coverage that reduces out-of-pocket costs when medical needs to arise. In other instances, some individuals may choose healthcare coverage with lower premiums, protecting against major medical costs, but requiring them to spend more of their own money to meet initial medical costs each year (i.e., with higher annual deductibles).

To help mitigate the financial burden of those higher deductibles, though some such high-deductible health insurance policies allow certain “covered” individuals to make contributions to Health Savings Accounts (HSAs), which offer a substantial “triple-tax” benefit (where contributions are tax-deductible, growth is tax-deferred, and qualified withdrawals are available tax-free) and are designed to be used for medical expenses.

The caveat to the various tax-saving benefits available to the HSA owner is that, like all other tax-preferenced accounts, HSAs require compliance with a number of rules, including limits around how much an HSA owner can contribute to the account, when funds can be used, and what counts as a “qualified” (eligible-for-tax-free) expense. Furthermore, compliance with these rules can become especially complex when married couples are collectively covered by more than one high-deductible health insurance plan (i.e., when each spouse is covered by their own plan, or when each is covered by multiple policies), where both spouses may potentially want to take advantage of the benefits of HSAs but must coordinate with each other in the process.

How Can Health Savings Accounts Benefit Taxpayers?

HSAs are a unique type of savings account because they are typically funded with the hope that most of the funds will never be needed (other than covering general routine doctor checkups) and that no major medical incidents will occur, which would create additional reasons for using HSA funds. Because usually, the goal for most (other types of) savings accounts is to eventually spend the funds on some desired outcome.

For instance, parents generally make contributions to a 529 plan with the hope of using those funds in the future to further their child’s education (because they want their children to go to college). Similarly, most contributions to retirement accounts are made with the intention of using those funds later in life (to enjoy a better retirement). But by contrast, no one ever really hopes that they’ll have major medical expenses.

Of course, the reality is that most people will incur significant out-of-pocket costs for healthcare over their lifetimes. That’s especially true for those who are contributing to HSAs as to do so, one must be enrolled in a “High-Deductible Health Plan” (HDHP, explained further below).

Health Savings Accounts (HSAs) Offer A Potential Trio Of Tax Benefits

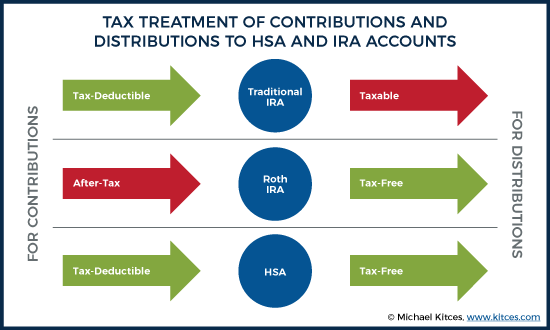

Of all the tax-favored accounts created by the Internal Revenue Code, the Health Savings Account arguably offers the best cumulative tax benefits, offering a unique trio of benefits not provided elsewhere in the Internal Revenue Code. These benefits include:

- the opportunity for tax-deductible contributions (a tax break on the way in);

- tax deferral of funds as they grow within the HSA shell; and

- the potential for tax-free distributions when used for qualified medical expenses (a tax break on the way out).

But while HSAs offer tax benefits (in the form of tax-free growth) when used for qualified medical expenses, it’s important to note that using HSA funds for medical expenses immediately as they arise can be a less efficient way to benefit from the account.

Rather, for those who can afford to pay for current medical expenses with other income/savings, the better way to use an HSA account is often to fund it, invest it, and let it grow, uninterrupted by distributions, for many years, and then using it for accumulated medical expenses down the road. By doing so, the HSA assets can compound, providing even more growth that can later be distributed and used tax-free.

Health Savings Accounts (HSAs) Not Used For Qualified Medical Expenses Become Enhanced Traditional IRAs After Age 65

For those individuals lucky enough to avoid material amounts of medical expenses over the years, the HSA offers attractive perks to be used later in life. Specifically, while HSA distributions that are not attributable to qualified medical expenses are generally taxable and subject to an additional 20% penalty (thus the benefit of using an HSA for medical expenses!), IRC Section 223(f)(4)(C) eliminates the 20% non-qualified withdrawal penalty once an individual reaches age 65.

Thus, after age 65, an HSA that is not used for qualified medical expenses essentially becomes a slightly better version of a traditional IRA, eligible for the same tax-deferred-with-future-taxable-withdrawals treatment, but with the distinction that while traditional IRAs are subject to required minimum distributions once an account owner reaches age 70 ½, HSAs have no distribution requirements during an owner’s lifetime! As such, in comparison to Traditional IRA owners, HSA owners can exercise a greater level of control over when to distribute funds from their account (and a greater duration over which they can be compounded tax-deferred in the meantime).

In other words, an HSA is similar to a traditional IRA, in that account contributions offer upfront tax deductions, funds grow tax-deferred, and distributions are subject to ordinary income tax. However, unlike the IRA, there is no required minimum distribution in place for the HSA, and distributions from an HSA for qualified medical expenses, in particular, are completely tax-free!

Tax Treatment Of Health Savings Accounts (HSAs) Upon Death Of The Owner

In the event an HSA owner dies before depleting all of the funds in their HSA (which has an increased risk when the HSA is deliberately accumulated and grown and not used for years or decades!), the treatment of funds remaining in the account at death will vary depending on the beneficiary of the HSA. More specifically, one set of rules is followed when the beneficiary is the decedent’s surviving spouse, and another set of rules is followed if the beneficiary is anyone else. Not surprisingly, surviving spouses receive more favorable treatment.

Per IRC Section 223(f)(8)(A), if an HSA owner’s spouse is the designated beneficiary, then upon the HSA owner’s death, the account becomes the surviving spouse’s own HSA account as of the date of death. (In practice, however, most custodians will require that the surviving spouse establish their own HSA account, tied to their own Social Security number, prior to taking any distributions.)

By contrast, when an HSA owner’s beneficiary is any person that is not the HSA owner’s spouse, then the account ceases to be treated as an HSA as of the date of the owner’s death. Any remaining funds in the account are treated as distributed to the beneficiary (not the original owner but the subsequent beneficiary) on the date of death, and thus, are taxable to the beneficiary in the year of the death (unless, as specified in IRC 223(f)(8)(B)(ii)(I), they are used to pay the decedent’s medical expenses within one year of the date of death).

In the event that an HSA owner’s beneficiary is their estate, IRC 223(f)(8)(B)(i)(II) requires that the remaining value of the HSA be included in the decedent’s income in the year of death.

Health Savings Account (HSA) Contributions Can (Only) Be Made By Certain Individuals With Qualifying High-Deductible Health Plans (HDHPs)

Notwithstanding the less favorable income tax consequences for an HSA that ends out never being used and left to a non-spouse beneficiary upon the death of the owner, the unique triple-tax benefits of an HSA make the account one that nearly every taxpayer would benefit from. Not all taxpayers, however, are eligible to contribute to such accounts in the first place!

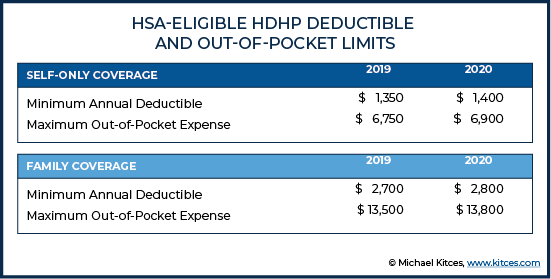

In order to contribute to an HSA, an individual must be covered by a qualifying High-Deductible Health Plan (HDHP). Qualifying HDHPs are health insurance plans that both incorporate a minimum annual deductible amount (i.e., it must be a high deductible), and an annual out-out-pocket maximum amount (limiting just how high that high deductible can be), both of which are set by the IRS. Since not all HDHPs meet these requirements, individuals who want to establish an HSA account should be careful to choose the right HDHP (or at the very least, inquire about whether their HDHP option meets those requirements). For instance, some plan deductibles are high enough that they exceed the out-of-pocket maximum – these HDHPs would not qualify an individual to contribute to an HSA.

For 2019 and 2020, the minimum annual deductibles and maximum out-of-pocket expenses for self-only and family (defined as an HDHP that provides coverage for the policyholder and at least one other person) coverage are as follows:

Furthermore, HSA-eligible HDHPs are prohibited from offering “first-dollar coverage”, in which the insurer provides coverage of co-pays or co-insurance amounts, right away. In other words, participants themselves are required to pay out-of-pocket for their initial medical expenses.

In addition to being covered by an HSA-eligible HDHP, in order to qualify to make an HSA contribution, an individual must also:

- not be enrolled in any other non-HSA-eligible high-deductible health plan (with limited exceptions), including Medicare and Tricare;

- not be claimed as a dependent on someone else’s return;

- not be enrolled in a Healthcare Flexible Spending Account (FSA), other than a Limited-Purpose FSA or a Post-Deductible FSA; and

- not be enrolled in a Health Reimbursement Account (HRA), other than a Limited-Purpose HSA, A Suspended HRA, A Post-Deductible HRA, a Retirement HRA, or certain QSE (Qualified Small Employer) HRAs.

Notably, while many individuals do not opt for coverage in an HSA-eligible HDHPs, such plans have gained significant traction in recent years. For instance, studies from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention show dramatic increases in the number of working-age individuals with HDHP coverage: between 2007 and 2017, the percentage of working-age adults with employment-based health insurance and enrolled in HDHPs increased from 14.8% to 43.4%.

Contributions To Health Savings Accounts Are Subject To Annual Maximum Amounts

Like other tax-favored retirement accounts, HSAs are subject to annual contribution limits. For persons with HSA-eligible self-only HDHP coverage for all of 2019, the maximum HSA contribution is $3,500 ($3,550 for 2020) while the maximum combined HSA contribution for 2019 for individuals covered by HSA-eligible family HDHP coverage for the entire year is $7,000 ($7,100 for 2020).

Note: For persons not covered for the full year under an HSA-eligible HDHP [or for those who switch from self-only coverage to family coverage mid-year], the annual contribution limit may be lower. In some situations, however, the “Last-Month Rule” may still allow a full year’s contribution to be made, provided the same coverage is maintained throughout a “Testing Period”. For more information, see IRS Publication 969, “Health Savings Accounts and Other Tax-Favored Health Plans”.

It's also worth noting that, like IRAs, HSAs are individual accounts. To that end, there is no such thing as a joint HSA. When one spouse is covered by an eligible HDHP, but the other is not, an HSA contribution can only be made to an account owned by the spouse who is covered by the eligible HDHP. On the other hand, when both spouses are covered under one HSA-eligible family HDHP, each spouse can open and fund their own HSA account. In other words, HSA accounts themselves are specific to the individual, but a high-deductible health insurance plan that is HSA-eligible can render multiple individuals covered under the plan as HSA-eligible.

Similar to the rules for other tax-preferenced accounts, the contribution limits for HSAs are increased for certain older HSA-eligible HDHP participants. More specifically, eligible individuals (persons who meet the requirements discussed above) who are 55 or older by the end of the year (unlike age 50 or older for “catch-up” contributions to retirement accounts) are eligible to contribute an additional $1,000 to their HSA account. In the event that both spouses of a married couple are eligible to make an HSA contribution, and both are 55 or older by the end of the year, then each spouse can make up to an additional $1,000 contribution to their own HSA.

Coordinating HSA Contributions When Both Spouses Are Covered By Separate High-Deductible Health Plans (HDHP)

In many situations, it is common for spouses to each be covered under separate health insurance policies, especially if both spouses are working. That’s because most employers tend to pay for a higher percentage of the cost of health insurance when just the employee is covered (single coverage), as opposed to when the employee elects to extend their employer-provided health insurance to additional family members (family coverage).

According to the Kaiser Family Foundation, in 2019, employees with individual health coverage pay, on average, 18% of the cost of their policy. Conversely, employees with family coverage in 2019 are ‘on the hook’ for 30% of the cost of coverage. Thus, when both spouses are working and have the option to participate in employer-provided health coverage, it is often more cost-effective for each to be covered separately under their own employer’s plan as an individual than to get one ‘family’ plan through either.

Given this reality, and the rise in the adoption of HSA-eligible HDHPs as a means of health insurance coverage, it is increasingly likely that spouses will each be covered by a separate HSA-eligible HDHP (as it would generally cost them less for such coverage than to have a single policy via one employer covering both individuals).

In such situations, advisors can help clients by coordinating HSA contributions between spouses to make sure that contributions to their HSAs don’t exceed the applicable contribution limits, as under IRC Section 4973(a)(5), any such overages are subject to a 6% excess contribution penalty for each year they remain in the account.

HSA Contribution Limits When Both Spouses Have Self-Only Coverage Via An HSA-Eligible High-Deductible Health Plan (HDHP)

Perhaps the most straightforward scenario that can apply is when each spouse has health insurance coverage via a separate HSA-eligible self-only HDHP. In such situations, each spouse may contribute to their own HSA up to the maximum for self-only HDHP coverage ($3,500 for 2019; with an additional $1,000 permitted for individuals age 55 and older).

Example 1a: Fred and Wilma are married and are each 31 years old. Both have self-only health coverage through their employer’s HSA-eligible HDHP.

Fred and Wilma understand the unique tax benefits offered by an HSA, and therefore, they’ve decided to sock away as much as possible into their accounts. To maximize their contributions for 2019, Fred and Wilma must each contribute $3,500 into their own HSA.

If one spouse does not contribute the maximum amount, though, the other spouse cannot exceed the maximum contribution limit applicable to those with self-only HSA-eligible HDHP coverage to make up for the other spouse’s shortfall.

Example 1b: Barney and Betty are married and are each 56 years old. Both have self-only health coverage through their employer’s HSA-eligible HDHP.

Betty is concerned about future healthcare costs and wants to maximize contributions to their HSAs. Barney, on the other hand, doesn’t really worry too much about future medical costs, and would rather spend money on bowling than on HSA contributions.

As such, Barney contributes only $1,500 to his HSA for 2019, instead of the $3,500 + $1,000 = $4,500 maximum amount he can contribute.

Betty can contribute the maximum of $3,500 + $1,000 = $4,500 to her HSA for 2019 but is unable to contribute any additional amounts to make up for the amounts that Barney could have contributed to his HSA (but chose not to).

HSA Contribution Limits When One Spouse Has Self-Only Coverage And The Other Spouse Has "Employee-And-Children" Family Coverage Via An HSA-Eligible High-Deductible Health Plan (HDHP)

Another possible scenario that advisors may encounter is when one spouse has self-only coverage while the other spouse has family coverage. This situation is most likely to arise in situations where a married couple has children, each spouse has employer-sponsored and subsidized health insurance coverage, and the couple decides to put all the children under one spouse’s plan as a family (while still keeping the other spouse separate).

In some cases, it may be possible for one spouse to have self-only coverage, while the other spouse covers only themselves and the children via “employee and children” coverage. “Employee and children” coverage, when offered, is less expensive than “family” coverage (which would also include the policyholder’s spouse), but because an “employee and children” policy covers the policyholder and “at least one other person”, it is still considered “family” coverage for the purpose of determining the applicable HSA contribution limit.

Thus, in a situation where one spouse has the ability to purchase “employee and children” coverage, and the other spouse has access to a (highly subsidized) self-only coverage option through their employer, total premium costs may be less expensive than if a single policy was purchased through either spouse’s employer covering the whole family.

Note: While premium outlay may be less when coordinating coverage as described above, couples should carefully evaluate other potential costs. For example, regardless of when the maximum out-of-pocket deductible is met on the “employee and children” policy (which can be as high as $13,500 in 2019), the spouse with self-only coverage is responsible for their own medical expenses and must meet the deductible and out-of-pocket limits tied to their own policy.

When one spouse has coverage via an HSA-eligible employee-and-children family HDHP (for HSA contribution purposes), and the other spouse has a self-only HSA-eligible HDHP, the maximum amount that can be contributed, combined, to the couple’s HSA accounts for the year is the maximum family amount ($7,000 in 2019), plus any allowable catch-up contributions. In other words, the maximum combined amount that can be contributed to both spouse’s HSAs is the exact same amount that would apply if both spouses were covered under one HSA-eligible family HDHP! The fact that there’s an ‘extra’ plan – and even the possibility that one spouse is covered under two plans (their own individual plan, and a family member of the other plan) doesn’t change the family limitation in the aggregate (which is still ‘just’ two times the individual limit).

But while the maximum combined amount that can be contributed to the couple’s HSA accounts is the same, the fact that the spouses have different types of coverage does introduce a wrinkle. More specifically, the spouse with self-only coverage can contribute only up to the maximum allowable amount based on self-only coverage to their HSA ($3,500 in 2019), plus any allowable catch-up contribution, while the spouse with the family plan can contribute all the way up to the $7,000 (in 2019) family limit.

Example 2a: Charlie and Lucy are married and are each 31 years old. Lucy has employee-and-children family coverage through her employer’s HSA-eligible HDHP, while Charlie has self-only coverage through his separate employer’s HSA-eligible HDHP.

Lucy is concerned about their future healthcare costs and wants to maximize contributions to their HSAs. Charlie, on the other hand, contributes nothing to his own HSA.

Despite Charlie’s potential shortsightedness, Lucy can still ensure that they make the maximum combined contribution for 2019 by contributing $7,000 to her own HSA since she has an HSA-eligible family HDHP.(Though if she contributes the full $7,000, then Charlie will not be eligible to contribute at all anymore, as the family’s aggregate maximum will have been reached!)

Conversely, if the spouse with self-only coverage is 55 or under at the end of the year (i.e., not yet eligible for a catch-up contribution), then any amounts contributed to their own HSA will reduce the maximum amount that can be contributed to the HSA of the spouse with family coverage dollar-for-dollar.

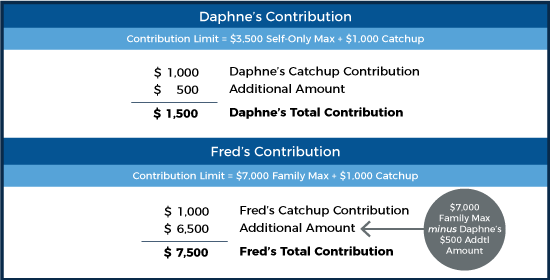

By contrast, if the spouse with self-only coverage is 55 or older by the end of the year, then any amounts contributed to their own HSA, above and beyond the $1,000 catch-up contribution amount, will reduce the maximum amount that can be contributed to the HSA of the spouse with family coverage dollar-for-dollar.

Put differently, contributions to the HSA of the spouse (age 55 or older) with self-only coverage first go towards meeting any allowable catch-up contribution limit and then begin to offset the amount that can be contributed to the HSA of the spouse with family coverage.

Example 2b: Fred and Daphne are married and are each 56 years old. Fred has employee-and-children family coverage through his employer’s HSA-eligible HDHP, while Daphne has self-only coverage through her separate employer’s HSA-eligible HDHP.

Fred wants to maximize contributions to their HSAs, but Daphne is less concerned about contributions and only saves $1,500 to her own HSA account.

The first $1,000 contributed to Daphne’s self-only account will go towards satisfying her catch-up contribution amount. The remaining $500 will reduce the amount that Fred can contribute to his HSA dollar-for-dollar. Thus, if Fred wants to maximize the couple’s combined HSA contributions for 2019, he must (but may only) contribute $7,000 - $500 = $6,500, plus his $1,000 catch-up contribution amount (for a total of $7,500) to his own HSA.

HSA Contribution Limits When Both Spouses Have Family Coverage Via An HSA-Eligible High-Deductible Health Plan (HDHP)

The final scenario to consider is when both spouses each have a family HSA-eligible HDHP that covers the other. This is, admittedly, less common, as it’s likely that the couple would opt for coverage under only one family HSA-eligible HDHP in order to reduce the premium costs and avoid paying for two plans (unless both family plans are fully subsidized by the employer).

Nevertheless, in situations where both spouses’ employers (generously) cover the full cost of an HSA-eligible family HDHP, or where the added premium cost of two such policies is worth it for some reason (such as the different in-network of doctors available in each plan), couples may find themselves in the unusual position where each spouse is covered by separate HSA-eligible family HDHPs.

Not surprisingly, being covered by two HSA-eligible family HDHPs does not increase the maximum allowable annual contribution beyond the regular maximum amount for family coverage. In fact, the contribution limits for such situations are exactly the same as they are when both spouses are covered under just one HSA-eligible family HDHP!

When both spouses are covered by separate HSA-eligible family HDHPs, the default is for the maximum family contribution limit to be split evenly between the two spouses. However, the couple can decide to divide the family maximum contribution limit however they see fit.

(Note: Provided the spouses’ combined contributions do not exceed the family maximum contribution amount, it is implicitly understood that their respective contribution amounts were determined in agreement. There is no special form or election that must be made.)

Of course, since a catch-up contribution for an individual can only be made to their own HSA (regardless of family contribution limit flexibility), in situations where both spouses are 55 or older, one spouse will have to contribute at least $1,000 to their own HSA in order for the couple to maximize their cumulative HSA contributions for the year.

Example 3: Hank and Peggy are married and are each 56 years old. Both of their employers cover the full cost of an HSA-eligible family HDHP, and thus, Hank and Peggy are each covered by both policies.

Hank and Peggy want to maximize contributions to their HSAs for 2019. Given their ages (both are old enough for the catch-up contribution), they are able to contribute as much as $7,000 (family limit) + $1,000 (Hank’s catchup) + $1,000 (Peggy’s catchup) = $9,000 to their HSAs for 2019.

However, in order to do so, Hank and Peggy each need to make catch-up contributions to their respective HSA accounts. The remaining $7,000 of ‘regular’ contributions, however, can be split between their accounts however they see fit.

Strategies To Maximize The Value Of Multiple Health Savings Accounts

As noted above, when both spouses have coverage via an HSA-eligible HDHP, there is often flexibility as to how the maximum HSA contribution can be allocated between the two spouses’ HSA accounts. That, however, doesn’t mean that it does not matter when or where those contributions are made for maximum efficiency!

Prioritize Health Savings Account (HSA) Contributions To The Older Spouse’s Account

When two spouses are different ages and at least one is under age 65, contributions should be skewed, to the extent possible, to the older spouse’s HSA. Recall that HSA distributions used to pay or reimburse the HSA owner for qualified medical expenses are tax- and penalty-free regardless of whether the HSA owner has reached age 65.

By contrast, when HSA distributions are made without reimbursable qualified health expenses, the treatment is markedly different for those who have reached age 65 compared with those who have not yet reached that ‘magic’ age. More specifically, while such non-medical-expense distributions before and after age 65 are subject to ordinary income tax, only distributions made before age 65 are subject to the additional 20% penalty. And so, by prioritizing contributions to the older spouse’s HSA, more of the funds will be available should the need to distribute funds for non-qualified expenses arise, thereby increasing the likelihood of avoiding the 20% penalty.

In the event that the younger spouse has already reached age 65, themselves, the preference to concentrate contributions in the older spouse’s HSA can be discarded if contributions are still being made to the HSA (a scenario that would generally require the spouses to be covered by a large employer’s group plan, or else Medicare would become the couple’s primary insurer and HSA contributions would no longer be allowed), as the tax treatment for all distributions would now apply equally to both spouses.

Finally, while an older spouse is typically more likely to predecease a younger spouse, that fact does not change the contribute-to-the-older-spouse’s-HSA-first strategy – recall that when a spouse is named as an HSA owner’s beneficiary, the HSA remains an HSA and is deemed to belong to the surviving spouse’s HSA upon the owner’s death.

So as long as spouses name each other as designated beneficiaries on their accounts (something advisors should always double-check), the surviving spouse will have access to the HSA funds in the same manner as though they had been contributed to their HSA directly, in the first place!

Prioritize Health Savings Account (HSA) Spending For Qualified Medical Expenses From The Younger Spouse’s Account

Following the same logic of prioritizing contributions to an older spouse’s account, when/if HSA distributions are needed/desired to cover medical expenses, such distributions should first come from the younger spouse’s HSA account. This leaves more funds available in the older spouse’s account, which once again, is more likely to result in penalty-free (though not tax-free) distribution of funds needed to cover unqualified, non-medical expenses.

Of course, by prioritizing contributions to the older spouse’s HSA (as outlined above), the younger spouse’s HSA would be kept to a minimum. Nevertheless, such funds still may exist because:

- Contributions were made to the younger spouse’s HSA prior to marriage;

- Contributions were made to the younger spouse’s HSA because the benefits of contributing to the older spouse’s HSA had not previously been made clear;

- The couple wants to split HSA contributions just to keep things ‘fair’;

- Each spouse is covered by a self-only HDHP; or

- The younger spouse is already 55 or older, and thus, must contribute at least the $1,000 catch-up contribution to their own HSA in order to maximize total family HSA contributions.

Regardless of the reason a younger spouse’s HSA is funded, it generally makes sense to spend such dollars first, provided that they are being used to pay for qualified medical expenses. Doing so, of course, preserves more of the older, first-to-reach-age-65 spouse’s HSA funds.

Once both spouses reach age 65, the spend-from-the-younger-spouse’s-HSA-first strategy can be discarded, as all future distributions from both spouse’s HSA accounts would receive the same tax treatment.

Health Savings Accounts offer a unique set of benefits not found elsewhere in the Internal Revenue Code. As such, individuals who can afford to contribute to such accounts allowed under law should do so to the extent that they are able.

When only one spouse of a married couple is covered by an HSA-eligible HDHP, the contribution rules are fairly straightforward, as they are when both spouses are covered under one HSA-eligible family HDHP.

However, when there is more than one HSA-eligible HDHP covering married spouses (either as self-only and/or family coverage plans), determining “Who?” can contribute “How much?” can become more challenging, especially given that individual HSA limits must be coordinated across families, and catch-up contribution limits always remain separate within families. Of course, it also opens the door to planning opportunities that may not otherwise be available, such as shifting HSA dollars specifically to the older spouse who is closer to being able to use such an account for more flexible (non-medical-expense) purposes without additional penalties (albeit still being fully taxable if not used for qualified medical expenses).

The bottom line, though, is that managing healthcare costs is a real concern for many individuals. But by helping clients maximize contributions to available HSA accounts, coordinating those contributions so that, to the extent possible, they are made to the right (typically the older) spouse’s HSA, spending down the right (typically younger spouse’s) HSA account first, and ensuring that as much of an HSA distribution is tax-free as allowed under law encouraging the recording maintenance of records related to previously unreimbursed qualified medical expenses, advisors can go a long way to alleviate those concerns.

check out this insirance plan: https://www.ladieshabits.com/post/Find-the-best-health-Insurrance-plan-for-you/0

My wife will be starting with a new HD plan on 1/1/2020. She was previously on a Cobra plan (not-HSA) provided by my previous employer, which will end on 12/31/2019. I’m on Medicare, but she won’t be for a few more years. We have set up an HSA for her but have not funded it yet. Should we wait until 1/1/2020 to make any contributions to the HSA? Or would it be possible for us to make contributions for 2019 as well? I haven’t been able to find any specific guidance on this, but it seems to me that we should wait until 2020 since that’s when her HD plan coverage begins.

I am 56 and my husband is 65, we are both employed and both covered under his companies HDHP Family Plan. Beginning in January 2020, he is discontinuing participation in the HSA because he is going to draw Medicare beginning in July 2020. He is not retiring for several more years. My question is…..since I am covered under his HDHP account, can I open a separate HSA account outside of his company and what are my tax benefits in that scenario?

Yes, as long as your only medical coverage is the HDHP then you can contribute to your own HSA titled in your name. You’ll be limited to single person contributions, according to IRS Pub 969.

In fact, you both should have your own HSAs anyway as the only way to make the extra $1,000 catch-up contribution is to your separate accounts. You can still do this for 2019 until regular tax filing deadline (usually April 15).

I’m a self employed advisor covered under my wife’s HDHP. She’s only contributed $2400 (through payroll) this year to her HSA.Can I open an HSA in my name with Fidelity and contribute the remaining $4600 to hit the maximum since I’m covered under her plan? We’re both under 55. Would this $4600 contribution then reduce my schedule C income?

I didn’t see info on integrating employer contributions to the HSAs which is combined with employee contributions for limit purposes. This is straight-forward except for two working spouses who get separate employer contributions which require additional thought about contribution limits and the requirements necessary to receive the employer contribution. Sometimes the employer contribution is increased for family coverage meaning it may make sense to split kids under two family HDHPs for each spouse or some other considerations.

As Kaleb mentioned, HSA contributions are subject to State income taxes in CA and NJ. In my experience, one factor to consider if choosing an HSA custodian for CA and NJ residents may be whether the custodian provides information on earnings within the HSA. The Form 1099-SA does not provide earnings information (except on excess contributions). I have noticed though that some HSA custodians make it fairly straightforward to log in to the HSA account online and view the earnings history (to use when preparing CA or NJ income tax returns). Other custodians do not.

For people who save and invest their HSA balances, and pay medical expenses out of pocket, the only limitation to the look back period for claiming reimbursement is back to when the initial HSA was established. So a person/couple in retirement who has accumulated “excess” funds can simply reimburse themselves for prior year expenses. Highly unlikely that they will actually need to declare ordinary income. I tell my clients to download their medical claims each year and save with their tax return documents in order to provide proof in the future if they want to take out any excess.

Absolutely correct, and likely the subject of a future article here! 🙂

When you write this article, I’m really curious about your thoughts on the realistic time frame in the past that someone might reimburse for QMEs from their HSA? To me, it seems the risk of early death means you’re taking a bit of a risk delaying for many years when you’ve accumulated a substantial amount in unreimbursed qualified expenses. IRS Pub 969 only exempts expenses paid by a beneficiary on behalf of the decedent within one year of death, so unless I’m missing something it wouldn’t be wise to delay tax-free withdrawals for years on end.

Don’t forget about the payroll tax benefits HSAs have over IRAs and 401(k)s. You might say HSAs are quadruple tax advantaged.

So glad you mentioned this Thomas! Most advisors and clients have no idea HSA contributions avoid FICA/FUDA taxes, which 401(k) contributions DO NOT avoid. That’s another 7.65% savings!! And except in CA and NJ, the HSA contributions avoid state income taxes. (Sorry CA and NJ peeps.)

Great point Tom! Definitely an added bonus for making contributions via payroll deduction!

In the case where both spouses are age 55 or older, but there is only one HDHP and both spouses are covered under this family plan…are both spouses able to contribute the extra $1,000 catch up provided that each spouse has their own HSA account?

Yes, see the following excerpt from the above article (emphasis added)

“In the event that both spouses of a married couple are eligible to make an HSA contribution, and both are 55 or older by the end of the year, then each spouse can make up to an additional $1,000 contribution to their own HSA.“

what about for 2020, i am seeking clarification for when each spouse is covered by his/her own family HDHP for him/her and his/her respective kids (separate… he (age 59) has coverage for him and his kids in his employer HDHP, and she (age 55) has coverage for her and her kids in her employer HDHP), is the family maximum still applicable at $9,000 or would each spouse have the $7,100 plus the $1000 catch up (so $8100 per spouse)? or would they be limited to the family max of $9000… for 2020? the nuance is in parentheses above.

Yes.

From IRS Pub 969: “If both spouses are 55 or older and not enrolled in Medicare, each spouse’s contribution limit is increased by the additional contribution. If both spouses meet the age requirement, the total contributions under family coverage can’t be more than $8,900. Each spouse must make the additional contribution to his or her own HSA.”

An example follows this. Basically, spouses can split the regular contribution any way they wish, but the $1,000 catch up must be contributed to accounts titled in each individual’s name.

Facts and musings about HSAs:

1. These are great accounts to accumulate wealth, but bad accounts to die with if your beneficiary is not your spouse. If you don’t have a spouse, making a withdrawal on your deathbed is a great idea. Alternatively you could make your beneficiary a charity. The charity is tax-exempt and won’t have to pay taxes on the proceeds.

2. As the article said, the best way to use an HSA is to accumulate and not pay medical expenses with the account. You should be investing the account, but many providers do not offer investments or charge high fees.

3. I don’t think you are required to use your employers choice for an HSA. As long as you have an HDHP, you can open an HSA anywhere and contribute to it. There is no advantage to using your employer’s HSA unless the employer pays the fees and/or contributes to your account.

4. You can move your HSA by doing a direct transfer to any provider. You may have to leave your employer, but this is not a government rule, so for some plans you can move the funds any time. So if your employer’s HSA does not provide good investment options, just move the money.

David,

Regarding No. 1, since there is no age limit on Roth contributions; if one spouse is still working (and assuming they are under the AGI limitations), as both spouses pass age 65, why not systematically drain the HSA’s and contribute to Roths?

If you need the money from the HSA to pay for the ROTH, then sure. But if not, you can keep the HSA going without additional contribution plus contribute to the ROTH. You can drain the HSA at any time, Meanwhile you get tax-free gains in both accounts. I would just say make sure you do it before death unless using a charitable beneficiary. BTW, this is all general information. Since I don’t know any reader’s specific situation, this is not specific advice.

On #3 above, don’t you have to contribute through payroll with employer salary reduction to take advantage of the payroll tax savings on the contribution? If you choose another HSA provider my understanding is employers typically will not fund those “outside” HSAs through salary reduction.

You are right Thomas. Not paying payroll taxes is a benefit of contributing to your employer’s HSA. As Jason points out, you can periodically transfer your balance to your custodian of choice.

Yes, you have to contribute through payroll to avoid the payroll taxes. People in this situation could TOA assets to another HSA of their choice periodically.

I worked thru October 2019 and was covered by a family high deductible plan. I contributed $1000 to my HSA. Got payed off and Switched to wife’s benefits for Nov/Dec, also a high deductible family plan. She is trying to max out her $7,000 contribution by years end. Can I also deposit $6,000 additional dollars into my HSA? That would be $7k into each plan for the year 2019.

No. Max for the both of you combined is 7,000. If you already contributed 1,000, your wife should make sure not to contribute more than 6,000.

HSA contributions are prorated for the time with an HDHP and whether or not you had a family plan. In your case, you can contribute 8/12 of $7000 to your HSA and then 2/12 of $7000 to your wife’s HSA for 2019.

My plan administrator, Fidelity, is telling me I can just jam the next $6k into my wife’s HSA ties to her HDO which covers us 11/1/19 thru 12-31-19.

We already set hers up to contribute $7k between 11/1 and 12/31 so we need to either shorten that to $6k or file a form claiming an excess contribution otherwise face tax penalty.

From the facts you have presented, anything over a $7000 total contribution would be an excess contribution. Unless your wife is 55 or older. Then she is allowed an extra $1000 catch-up contribution. You might be allowed that for your HSA and I honestly don’t know the rules for the two HSAs if you both are over 55.

Note that for a single HSA, only the owner is allowed to make the catch-up contribution based on their age.

Two super-fun HSA tricks: 1.) When a non-dependent child is covered by a family HSA-eligible plan, both the parent(s) and the child may contribute the full family max to separate HSA (i.e. two separate $7,000 contributions). 2.) HSAs may be funded up to the annual limit by a transfer from IRAs – including inherited IRAs! – once in a lifetime.

Glad you mentioned #1. Also applies to domestic partners who cover each other but file taxes as individuals.

Great article but I don’t believe this is accurate: “In this situation, the spouse with self-only coverage is limited to the self-only HSA contribution amount, and the spouse with family coverage can contribute up to the family limit.” See IRS Notice 2008-59, Q/A 17 with this specific example. They can divide up to the family limit by agreement, “regardless of whether the family HDHP coverage includes the spouse with self-only coverage”.

Lynne,

Thanks for taking the time to read and to comment. The difference between the situation being described in the article above and the example from Notice 2008-59 is in the Notice, both spouses are covered by a Family HDHP. When that’s the case, the contribution is, by default, split between the spouses, but can be altered by mutual agreement. In the article above, however, we’re talking about a situation where one spouse is covered only by a self-only HDHP, and the other spouse is covered by Employee and Children coverage, which does NOT cover the other spouse, but is still considered Family coverage for HSA contribution purposes.

I don’t think this distinction was as clear as it could/should have been, so we’ve updated the article in several places to re-emphasize the fact pattern.

Thanks for helping us make that clearer for future readers!

Best,

Jeff

Please check that notice again:

The notice states “One spouse has family HDHP coverage and the other spouse has self-only HDHP coverage” then also says “This is the result regardless of whether the family HDHP coverage includes the spouse with self-only HDHP coverage”.

It does not matter, if spouse is covered by the family plan or not, and as you said “employee+1, or “employee and children” = Family coverage.

In 2019 my husband and I started the year on separate HSA plans, and each contributed monthly. Then in May, our child was born and we switched to my HSA plan as a family. We are now trying to reconcile the difference in order to hit our maximum of $7,000. Does it matter which account we contribute the difference? Does his HSA have a maximum contribution amount since he was not covered the entire year?

For IRS rules, it does not matter which HSA contributions go into, long as the owner of that HSA qualifies. So if you both qualify, you can contribute to either HSA. IRS Pub 969 confirms that regardless of your situation, families cannot contribute more than the family limit across two or more HSAs, so you’ll need to reduce your own contributions by whatever amount he already contributed to his account.

For tax savings, if your employer facilitates payroll contributions to your HSA, that method will save you the SS and Medicare taxes on your contributions.

Having and HSA and an HRA….my husband has a HDHP-HRA, covering our children. I have a HDHP-HSA, only covering myself. Can I contribute up to the family maximum. Do I need to deduct the employer contribution on the HRA? And May I use my HSA to pay for out of pocket expenses once the employer contributions are used from the HRA?

I’m still confused about rules for the 55 and over catch-up. What if both are over 55, having a “family” HDHP for just two of them, and have separate HSAs, do they each get the 1k catch-up? i.e. each can contribute up to individual amount plus catch-up. If not, would that be a better solution to have individual HDHP for each of them so each can have a 1k catch-up contribution?

After looking into HSAs (due to a large coinsurance payment coming up), I went down to my local credit union to open an account. All they asked me about was the amount of the deductible and whether my kids are on my plan with me (they are- spouse has a separate individual plan with the same company). She recommended (and I opened) a family HSA. Now I see this “out of pocket maximum” requirement. My plan DOES meet both requirements (deductible & out of pocket) for the INDIVIDUAL plan but only the deductible for the family plan (my out of pocket max is $5,900 for individual and $16,300). Am I actually even eligible for an HSA, even as an individual?