Executive Summary

A reverse mortgage allows homeowners to borrow against their primary residence, without making any ongoing payments; instead, interest simply accrues on top of the principal, and most commonly is not repaid until the homeowner either moves and sells the home, or when it is sold by heirs after the original owner passes away.

The caveat, however, is that if reverse mortgage interest accrues annually instead of being paid, it cannot be deducted each year under the “normal” rules for deducting mortgage interest. And a similar caveat applies to mortgage insurance premiums, which might be deducted (at least, if Congress reinstates and extends the rules that lapsed at the end of 2017), but only if they’re actually paid – which, again, typically isn’t the case with a no-payment reverse mortgage.

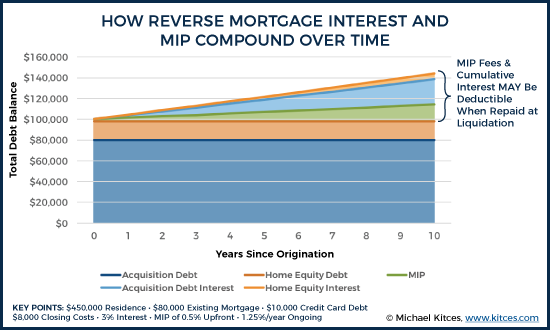

Of course, the reality is that when the loan is ultimately repaid in full – even if all at once – the accrued mortgage interest and mortgage insurance premiums do become deductible at that time when actually paid. The problem, though, is that if compounded for enough years, the size of the deduction may be too large to use… or at least, the liquidating homeowner (or heir) may need to plan to create income in the year the reverse mortgage is paid off, just to ensure there’s enough income to be offset by the deductions.

Furthermore, reverse mortgages can also complicate the tax deductibility of real estate taxes. To the extent real estate taxes are paid directly – even as a cash payment with proceeds from a reverse mortgage – they remain deductible. However, with the HECM reverse mortgage’s new Life Expectancy Set Aside (LESA) rules, it’s not entirely clear whether real estate taxes paid directly from the set aside are fully deductible in the same manner, or whether they might have to be accrued and claimed at liquidation, similar to the reverse mortgage interest deduction and mortgage insurance premium deduction!

Taxability Of HECM Reverse Mortgage Loans And “Income”

One of the most popular selling points of a HECM reverse mortgage is that the money received is “tax-free”.

In reality, cash paid out from a reverse mortgage, whether as a lump sum or ongoing “income” payments, is tax-free simply because it’s ultimately nothing more than a loan against an existing asset. In other words, no income or wealth is created in the first place; the borrower is simply taking out a personal loan and using his/her primary residence as the collateral, which isn’t any more taxable than getting a loan to buy a car or pay for college, or taking out a home equity line of credit or borrowing against a life insurance policy.

The fact that the borrower may use periodic cash flows received from the loan as an “income” substitute to pay his/her bills, fortunately, doesn’t cause the loan to become taxable. It’s still a loan, and as a result, the cash payments remain a non-taxable receipt of loan proceeds against an existing asset, just like other types of (secured or unsecured) loans. Regardless of whether the reverse mortgage is an upfront lump sum, a line of credit that’s drawn against periodically, or tenure payments for life.

Notably, the fact that a reverse mortgage loan isn’t income for tax purposes, also means it doesn’t impact other tax-related issues for retirees, like the taxability of Social Security payments or income-related premium surcharges for Medicare Parts B and D. Because, again, while it might be colloquially called “income” for household cash flow purposes, in practice it’s simply a loan (subject to certain reverse mortgage terms and borrowing requirements).

Deductibility Of HECM Reverse Mortgage Interest

While the tax treatment of the proceeds from a HECM reverse mortgage loan is rather straightforward (it's nontaxable), there is far more tax complexity when it comes to the deductibility of reverse mortgage interest. This is due both to the limitations of the general rules for deducting mortgage interest in the context of how reverse mortgages are typically used, and also because of the way that reverse mortgage interest is usually paid (not on an ongoing basis as occurs with traditional mortgages).

Standard Tax Rules For Deducting Mortgage Interest

The standard rules under IRC Section 163(h) is that “personal” interest is not tax deductible. But there is an exception under IRC Section 163(h)(3) that allows a deduction for payments of “qualified residence interest” – i.e., mortgage interest that is classified as either “acquisition indebtedness” or “home equity indebtedness”.

Acquisition indebtedness is a mortgage debt incurred to acquire, build, or substantially improve either a primary residence or a designed second home. Home equity indebtedness is any type of primary residence or second home mortgage debt that doesn’t qualify as acquisition indebtedness.

The classifications of mortgage debt are important because of the limitations. Interest on the first $1,000,000 of acquisition debt principal is deductible, but taxpayers can only deduct the interest on the first $100,000 of home equity indebtedness. In addition, interest on home equity indebtedness is an AMT adjustment (which means the deduction is lost entirely for those already paying AMT).

Notably, the rules classifying mortgage debt are based not on what the mortgage is called by the lender, but how the loan proceeds are actually used. Thus, a home equity line of credit to build an expansion on the home is “acquisition debt”, but a cash-out refinance of a 30-year mortgage used to consolidate and repay credit card debt is home equity indebtedness (at least for the additional cash-out portion of the loan). And a mortgage against a primary residence taken out when it’s purchased is acquisition debt (as the loan was used to buy the property), but if the owner buys the property with cash and later does a cash-out refinance for the exact same mortgage amount and terms will have the interest treated as home equity indebtedness (because the loan proceeds weren’t used to acquire the residence, since it had already been acquired at that point).

It’s also important to note that mortgage interest deductibility is further limited to a debt balance that does not exceed the original purchase price of the home (adjusted for reinvestments for home improvements) under Treasury Regulation 1.163-10T(c)(1). Thus, for instance, if the original purchase price was $300,000 and a home expansion increased the adjusted purchase price to $350,000, the owner can never deduct mortgage interest on more than $350,000 of mortgage debt. In most typical traditional mortgage situations, this is a non-issue, as the mortgage would typically start at $300,000 or less, and amortize down over time. However, the issue can arise if the house appreciates in value and a subsequent cash-out refinance increases the mortgage balance above the original purchase price (plus improvements). And it can also be a limiting factor for negative amortization loans (where the interest compounds against the loan balance over time), which as discussed below, includes reverse mortgages.

In addition to the rules to deduct primary residence mortgage interest, there are also rules to deduct interest for investment real estate or to claim interest as a deduction against rental real estate, but those rules are a moot point for a reverse mortgage since a reverse mortgage must be against your primary residence.

Deducting Reverse Mortgage Interest Payments

In the case of a reverse mortgage, it is still indebtedness against a primary residence, which means the same rules apply to deduct reverse mortgage interest, including the determination of whether the loan balance will be classified as acquisition debt or home equity indebtedness depends on how the money is used. Thus, if the borrower takes out an upfront lump-sum reverse mortgage to refinance other debt, it’s home equity indebtedness; if the reverse mortgage is used to buy a new retirement home, or to make home modifications on your existing home for your retirement, it can be acquisition debt.

Fortunately, a new mortgage that is simply refinancing of existing acquisition debt continues to count as acquisition debt as well, which means a reverse mortgage used to refinance a traditional mortgage can also be acquisition debt (if the original mortgage was in the first place). Though notably, even if the reverse mortgage is acquisition debt and its interest is deductible as such, technically the interest on the interest that may accrue in a negatively amortizing reverse mortgage should be treated as home equity indebtedness (although the calculation of it would be complex, and it would be difficult for the IRS to track as well since there is no automatic reporting process to the IRS about the type of mortgage debt).

However, the important caveat to the reverse mortgage interest deduction is that under IRC Section 163(h), the interest is only deductible when it is actually paid. Which is a big deal for a reverse mortgage, because the borrower is typically not making interest (or any payments) on an ongoing basis! He/she may choose to make ongoing payments - which are applied to the aggregated accumulated Mortgage Insurance Premiums, then cumulative servicing fees that have accrued, and then finally accrued interest that may be deductible (per the Model Loan terms for a HECM reverse mortgage). But most commonly, interest (and the other expenses) simply accrues on top of the reverse mortgage principal over time (since the whole point of the reverse mortgage is often to relieve the cash flow obligation of making ongoing payments). Yet if the reverse mortgage just accrues and compounds, there is no mortgage interest deduction on a year-by-year basis, because it’s not actually being paid.

Instead, the cumulative loan interest is often repaid when the reverse mortgage finally “terminates” – either because the borrower ceased to use his/her the property as his/her primary residence, decided to repay the loan, or in many cases because he/she passed away and the property is being liquidated by the estate or heirs in order to repay the loan.

Recovering A Lost Deduction For Reverse Mortgage Interest?

The problem with the typical lump sum repayment of a reverse mortgage is that when the cumulative loan interest is all repaid all at once – and thus would be claimed as a deduction all at once when paid – then there is a realistic risk that the accrued debt could exceed the adjusted purchase price (which limits the deductibility). Furthermore, there’s a risk that a large portion of the mortgage interest deduction could be lost entirely, because the taxpayer may not have enough income to be offset by the deduction!

In their Journal of Taxation article “Recovering A Lost Deduction”, Sacks et al. explore the dynamics of how to avoid losing (or recover) the tax benefits of the reverse mortgage interest deduction, when loan interest is accrued and repayment in a single year could cause negative taxable income (where deductions exceed income, and the excess deductions are unable to be used and cannot be carried forward).

The most straightforward way to resolve this issue is simply to plan that, in the tax year the reverse mortgage is (going to be) repaid, the owner will create taxable income if necessary, to ensure that there is income that can then be absorbed by the mortgage interest deduction. This might be accomplished with an IRA distribution, a partial Roth conversion, or simply by ensuring that the owner’s total income from other sources is sufficient to fully offset the available deduction. If the primary residence had appreciated enough – such that there’s a capital gain even after the up-to-$500,000 capital gain exclusion for the sale of a primary residence – the excess capital gains are also “income” that can be offset by the mortgage interest deduction (and while the deduction is less valuable when applied against a capital gain instead of ordinary income, it’s still better than being lost altogether because there isn’t enough income at all!).

In many cases, though, the situation is further complicated by the fact that in reverse mortgage payoff scenarios, there’s often a question of who gets to claim the interest, since the reverse mortgage may be repaid because/after the original homeowner dies. Which means it’s a tax issue for the estate or the heirs, not the original borrower/homeowner!

Fortunately, Treasury Regulation 1.691(b)-1 does allow a decedent’s prospective deductible items that hadn’t been paid at death to be deducted subsequently when paid by beneficiaries. However, in many cases, the beneficiaries don’t have enough income either, especially when the estate inherits the house to liquidate but doesn’t inherit pre-tax retirement accounts that might have created taxable income (as the retirement accounts typically go directly to beneficiaries by beneficiary designation).

Accordingly, consideration should be given to who will inherit a property subject to a reverse mortgage that might be repaid after death, and whether he/she will have sufficient income to offset/absorb the available deduction. This might mean ensuring the house passes directly to heirs that receive other assets (e.g., with a Transfer on Death rule) rather than just bequesting it under the will, or at least give the executor the flexibility to distribute the residence and mortgage in-kind for beneficiaries to subsequently liquidate (to claim the deduction on their own tax returns, where they have more assets that might create income that can be offset by the deduction, including recently inherited IRAs!).

Alternatively, the borrower can avoid the potential clustering of the reverse mortgage’s interest deduction payment at death by voluntarily paying the interest annually along the way. However, this would require truly paying the interest – not merely having it accrue against the reverse mortgage, or paying it and then immediately repaying yourself from the reverse mortgage – and may or may not be manageable for the retiree’s cash flow (especially since payments aren't applied against interest until the accrued MIP and servicing fees are repaid, first!).

In addition, it’s notable that paying the mortgage interest on an ongoing basis is only deductible if the borrower actually itemizes deductions in the first place, which isn’t always the case for retirees, especially in the future if the standard deduction is increased in 2017 and beyond under the President Trump or House GOP tax reform proposals. If the standard deduction ends up being higher and itemized deductions are indirectly curtailed for many retirees, it might actually become more desirable to simply allow the mortgage interest to accrue and be “bunched together” to repay at the end – though, again, it’s still necessary to ensure there’s at least enough income in that liquidation/repayment year to actually absorb the full deduction at that time.

Deducting The Mortgage Insurance Premium Of A HECM Reverse Mortgage

In addition to the potential deduction for a reverse mortgage’s mortgage interest payments, taxpayers can also potentially deduct mortgage insurance premiums as mortgage (“qualified personal residence”) interest, under IRC Section 163(h)(3)(E). However, to claim the MIP deduction, it’s necessary that the mortgage itself have been issued since January 1st of 2007, and that the reverse mortgage debt itself be classified as acquisition indebtedness and not home equity indebtedness. As a result, the deductibility of the MIP will be contingent on how the proceeds of the reverse mortgage are actually being used (to determine whether it qualifies as acquisition indebtedness in the first place).

The deductibility of a mortgage insurance premium (MIP) is highly relevant for reverse mortgages, given that they have both an upfront MIP of 0.50% to 2.50% and an ongoing MIP of 1.25%.

Again, though, payments – whether for mortgage interest or mortgage insurance premiums – are only deductible when actually paid, which means that when the upfront MIP is rolled into the reverse mortgage balance and the annual MIP is accrued on top of the mortgage balance, the payments haven’t been made, and thus, the MIP cost can’t be deducted. Instead, as with mortgage interest, if the payments aren’t actually made until the property is liquidated and the reverse mortgage is paid off in full, then the MIP will solely be deductible at that time, all at once, and face the same issue regarding whether there’s enough income available to absorb the deduction. If ongoing payments to the reverse mortgage are made, the MIP may be deductible (if otherwise eligible), and notably repayments to a reverse mortgage are presumed to be allocated towards the (accrued upfront and ongoing) MIP first.

In the case of the MIP deduction, the situation is further complicated by the fact that the MIP deduction begins to phase out above $100,000 of AGI (for both individuals and married couples filing jointly), and fully phases out once AGI reaches $109,001. Thus, if the MIP deduction comes due all at once, it may create income against which the deduction will be offset can also push the taxpayer over the line where none of the MIP is deductible anyway.

In practice, though, these constraints may prove to be a moot point, as technically the deduction for mortgage insurance premiums was last extended under the PATH Act of 2015 through the end of 2016, and lapsed as of December 31 of 2016. Of course, it may ultimately be reinstated later in 2017 – and in point of fact, it has been retroactively reinstated after lapsing more than once in the past decade already. Or it could become a matter of permanent tax law under looming 2017 income tax reform. Nonetheless, as it stands now, MIP payments aren’t even deductible in 2017, much less in a distant future year when the property is finally sold and the reverse mortgage is liquidated in full.

Notably, even if the deduction for mortgage insurance premiums does get reinstated and stick around, the relative balances of mortgage insurance premiums, interest, and principal, are not directly tracked in the current Form 1098 reporting from the lender. Which means at best, the balances would have to be determined (or reconstructed retrospectively) from monthly reverse mortgage statements just to figure out how much of the MIP might be deductible.

How Reverse Mortgages Impact Real Estate Tax Deductions

One final point of tax complexity with a reverse mortgage is how to handle the tax treatment of real estate taxes that are paid via a reverse mortgage.

In general, the deductibility of paying real estate taxes follows the “normal” rules under IRC Section 164 – the taxes are deductible when actually paid. Thus, regular payments for real estate taxes through a mortgage servicer’s (as part of the full PITI monthly payment) are still deductible because they were actually paid (even if through the servicer’s escrow arrangement), and a direct payment of real estate taxes (e.g., to the county because the mortgage has already been paid off) are also deductible when paid.

For those who use a reverse mortgage to generate the cash to make the payment for real estate taxes – whether by drawing against the home equity line of credit, using the lump sum proceeds of a cash-out reverse mortgage, or paid via the ongoing tenure payments structure – the favorable tax treatment of real estate taxes is the same. From the tax code’s perspective, the fact that the taxpayer got the money to make the payment from a (reverse mortgage) loan is irrelevant; all that matters is that an actual payment was made, to satisfy the legal tax obligation.

The situation is somewhat more ambiguous in the case of real estate taxes that are paid directly from the HECM reverse mortgage, which can happen for taxpayers that fail to meet underwriting requirements and have a “Life Expectancy Set Aside” (LESA). The LESA rules are intended to ensure that reverse mortgage borrowers don’t unwittingly default on the reverse mortgage by failing to make property tax (and homeowner’s insurance) payments, by instead drawing those amounts directly from the reverse mortgage, holding them in escrow, and them remitting the payments for taxes and insurance as appropriate. In essence, the LESA rules ensure that the borrower doesn’t max out the reverse mortgage borrowing limit for other purposes, and then runs out money to pay taxes and insurance; instead, the reverse mortgage is carved out to pay the taxes and insurance, and the homeowner is left to be responsible for the rest of his/her bills (but without property taxes and homeowner’s insurance looming).

In the LESA scenario, the taxpayer doesn’t directly make a personal cash/check payment for property taxes, because the payment is drawn against the reverse mortgage balance and remitted directly to the county. Nonetheless, some argue that given that the legal tax obligation is satisfied and the taxpayer incurs an actual debt (an increase in the reverse mortgage balance) in the process, it should still be constructively treated as a “payment” for tax purposes at the time the property taxes are paid via the reverse mortgage, even if it wasn’t a personal cash outflow for the homeowner. Still, though, there is no definitive tax guidance to clarify the treatment, and more clearly distinguish why an increase in reverse mortgage debt balance for interest is not a deductible “payment” while a similar increase in the debt balance for a payment of real estate taxes is a deductible “payment”.

So what do you think? Have you had clients concerned about the tax rules for reverse mortgages? Will HECMs become more popular and increase the importance of reverse mortgage tax planning? Please share your thoughts in the comments below!

I read that Sacks article a couple weeks ago. You’ve provided a good synopsis and some additional considerations. Very good.

Calling reverse mortgage $ ‘Income’ is a silly. It’s cash flow. It’s an accounting adjustment, asset to cash flow. Nothing more.

A more interesting question:

Suppose a 62 YO homeowner takes out a $100K HECMLOC and lets it grow for 20 yrs. At 6% growth it’s worth $321K. The home is worth $200K and the homeowner takes the $321K and decides to walk, or dies just after s/he cashes out. Is this considered taxable ‘debt forgiveness?’ It just doesn’t appear to be so.

Do you think the exclusion for qualified principal indebtedness applies under 108(a)(1)(E) and 108(h) ? The tax attributes of this tax situation will make your head spin.

Mr. Reese,

Your point only makes sense in a recourse context. A reverse mortgage by federal law is nonrecourse. Since it is clear you have limited knowledge of the Internal Revenue Code, you might want to read 2016 Publication 4681 Section 2 when it comes to the difference between recourse and nonrecourse debt along with IRC Reg. Section 1.1001-2.

Just as I thought, and thanks!

Mr. Simone,

Please see my comment to Mr. Reese.

Two points: it is my understanding that it is HUD policy (not servicer or borrower choice) that any payments are first applied to accrued MIP, secondly to accrued interest, and thirdly to principal. When I engaged in periodic payments on my reverse mortgage, the Form 1098s reflected that allocation.

Secondly the LESA issue is of little or no practical consequence, since a LESA is only established when the borrower has a shortfall in residual income – which would mean in practice that they would hardly be in a position to itemize deductions.

Mr. Dean,

The prepayment (as it is called) allocation rule places Servicing Fees after MIP but before interest.

Jim,

Fair point about LESA, although there are potential situations where LESA was required at the time the reverse mortgage was taken out, but the individual’s asset/income situation later changed, to the point where now mortgage interest deductibility and itemizing deductions may now be on the table even where LESA applies.

Granted, though, you have a good point that at least “most” of the time, those impacted by LESA are probably those who aren’t itemizing deductions anyway. Thanks for mentioning this.

– Michael

Not true – at anytime a borrower may voluntary take a LESA. Since the LESA offers a growth rate which may further extend tax/ins. payments some find this as a convenient & unintended advantage. https://reverse.mortgage/voluntary-lesa

Very good article. However, there’s a major error here that a reverse mortgage borrower can “choose” to pay the interest annually, and therefore claim it as a tax deduction. But here’s the misconception that a lot of financial professionals have: As per FHA rules, the borrower can’t just designate where he/she wants a payment to go toward. In fact, every reverse mortgage lender or servicer, upon receiving any payment, regardless of the client’s request, must put that money first toward prepayment of the initial FHA mortgage insurance. And if/when that’s completely satisfied, any additional funds must go toward paying off the financed closing costs. After that, any monthly servicing fee. After that, the monthly FHA mortgage insurance fees. Only after all of those items have been completely satisfied, does any money go toward the accrued interest, which would then be tax-deductible in that calendar year.

Mr. Schluter,

The prepayment (so named) allocation rule requires that payments be applied in the following order until that category has no more unpaid but accrued cost: 1) ALL accrued but unpaid MIP (upfront and ongoing), 2) all accrued but unpaid servicing fees 3) by all accrued but unpaid interest and finally 4) principal. Closing costs are no different than any other principal used to pay the cost of borrowers. There is NO requirement that any payments be applied against accrued upfront costs (other than accrued but unpaid MIP) since it is principal.

There are cases where NONE of the paid interest is deductible so let us not assume that the total of all paid interest on a reverse mortgage are automatically deductible because they are not.

Rick and James,

Thanks for the comments on this.

Do you have a specific source/citation that I can reference for the FHA prepayment allocation rules? I’d like to update the article according, and include a source reference for those who want to delve deeper.

Thanks,

– Michael

Mr. Kitces,

Since regulations and Mortgagee Letters do not directly apply to borrowers, one must look at the model loan documents.

You will find in Section 6 titled: “The Borrower’s Right to Prepay” on Pages 3 of 9 and 4 of 9 of the following webpage:

https://portal.hud.gov/hudportal/documents/huddoc?id=HECM_Model_ARM_Note.pdf

You will find the mirror Section for HECM fixed rate Notes in the same documents section on the HUD website.

You’re a wealth of info on this topic James! Can I reach out to you as an expert on tax rules for our readers as well?

Mr. Auerswald,

Not a problem.

Thanks again for the guidance (with citation). We’ve updated the article accordingly to clarify these (pre)payment ordering rules!

– Michael

As always, great article. I am studying for the CFP and just went over reverse mortgages, so this article was a great read for me! Thank you.

My comments will be by subject. My first area of disagreement is the deduction of real estate taxes paid for by the servicer (or lender) under a LESA arrangement.

LESAs are not escrows. Escrows in a reverse mortgage context result from money being borrowed from the mortgage and cash being placed into an escrow generally governed by agreement with the fiduciary under state law. A set aside is simply a portion of the loan that must be used for the intended purpose or returned to the lender or borrower as additional amounts in the line of credit. With the fixed rate HECM it is returned to the lender and extinguished. LESAs are set asides as reflected in their name.

There are two basic kinds of LESAs, one is a partially funded LESA and the other is a fully funded LESA. The fully funded LESA can be either a voluntarily set aside by the borrower alone or involuntarily by the lender as part of the loan structure.

With a partially funded LESA the LESA payout is made to the borrower who is responsible to then pay all property charges. How can there be any question about the payment of a real estate tax by the homeowner in that case? Next let us look at the voluntary fully funded LESA. How is this any different than paying a real estate tax by credit card? Is this any different than a bill paying service paying bills on behalf of a customer or a payroll service paying the payroll taxes for an employer? Again this seems to be a very clear issue and the tax answer is that the real estate taxes are deductible in the tax year paid by the servicer (generally not the lender). The underlying obligation to the tax collector which never changes under these arrangements is that of the borrower, not that of the lender or servicer.

Finally we will look at involuntary fully funded LESAs. Again the arrangement is to protect the foreclosure position of the lender and is normally handled by a servicer. Neither the lender nor the servicer have any obligation other than to the borrower to make these payments, period. There is no arrangement between 1. the lender, servicer, or borrower 2) an insurer (for the homeowner’s insurance portion) or real estate tax collector. A LESA is an agreement between 1) the lender and servicer and 2) the borrower and the lender.

So is HECM MIP any different than the LESA arrangement? Absolutely. Only the lender can pay HUD for lender insurance. MIP is not insurance premiums for a borrower’s insurance policy and provides no particular protection to the borrower. The mortgage document(s) creates nonrecourse between the lender, borrower, and if applicable, HUD, no matter whether a HECM or proprietary reverse mortgage is involved. Federal law at 15 USC 1602(bb) states that a reverse mortgage transaction is a nonrecourse transaction. We can clearly point to the HECM loan documents in Section 11 on Page 6 of 14 at the following webpage ARMs to show it is the sole source of nonrecourse between lender and borrower:

https://portal.hud.gov/hudportal/documents/huddoc?id=HECM_Model_ARM_Note.pdf

The mirror provision can be found in the HECM fixed rate mortgage documents as well.

As to MIP, FHA is the insurer, and the lender is both insured and beneficiary. So when MIP is paid, it is the cost of the lender; however, the lender is permitted to pass the cost on to the borrower and in most cases does. So like interest, the borrower must pay the lender before MIP is a cash basis cost of the borrower. In theory, the cash that is paid out of the loan for MIP is both taken from and received by the lender which in the tax realm is not a cash basis expense of the borrower. It is not a deduction of the borrower until the borrower pays it to the lender.

Now let us come back to involuntary LESAs. The payment is no different than a bill paying service having permission to pay bills with the credit card or line of credit of the consumer. As long as the bill payer, credit provider, and consumer are all unrelated, arm’s length third parties, payments are considered made by the consumer at the time of receipt by the billing party. Since the servicer and lender are not related to the borrower and the tax collector is unrelated to any of those parties, how are the real estate taxes not deductible to borrower in the year paid for by the servicer/lender? Perhaps the IRS could come up with some absurd reasoning but as of now, that seems to be the correct answer. Further unless there is fraud in the transactions, the statute of limitations should only be open to the later of three years from filing the related tax return or two years from the date that tax payments are made to the US Treasury for those years.

There are two distinct categories of LESAs with HECMs and only HECMs, one of which has two subcategories. The LESA (Life Expectancy Set Aside) explanation above is both incomplete and inaccurate. Real estate taxes (and other deductible amounts) are fully deductible in the tax year paid while the tax year of deduction is perhaps open to some question in the last situation, involuntary fully funded LESAs. The amount of a LESA is subtracted from the funds available to the borrower and set aside until used. The HECM balance due is not increased by the LESA until either or property charges are actually paid (all fully funded LESAs) or to the borrower (partially funded LESAs). All LESAs are amortized monthly by one-twelfth of the sum of 1) the applicable note interest rate for the month and 2) the ongoing FHA MIP rate.

The first LESA category is a partially funded LESA and is not voluntary. That LESA only applies if its is less than the other category of LESA, the fully funded LESA, and is generally a capitalization of one hundred and twenty percent of the monthly amount of negative cash flow a borrower is projected to incur over the FHA HECM TALC life expectancy expressed in months; the capitalization rate is one-twelfth of the sum of 1) the HECM expected interest rate for that loan plus 2) the ongoing FHA MIP rate. It works very differently than the LESA described above in the post since the borrower is responsible for paying all property charges on time and in full.

The second category is the fully funded LESA. It is both voluntary and involuntary. Both fully funded LESAs are a capitalization of the one hundred and twenty percent of specifically defined current property charges. The period of capitalization and capitalization rate are the same as for the partially funded LESA. With the voluntary LESA, the borrower elects the servicer/lender as the agent to pay the applicable capitalized property charges. The voluntary LESA differs with the involuntary LESA in that only the borrower can voluntarily elect the voluntary fully funded LESA while the lender requires the involuntary LESA.

As to the partially LESA, property taxes are deductible when paid because they are the obligation of the payer who is also the borrower. As to voluntary fully funded LESAs, the borrower is electing the lender/servicer as the agent to pay the obligations of the borrower (not the obligation of either the lender or the servicer).

As to the involuntary fully funded LESA, since the obligation is not that of the lender (even when the loan is assigned to FHA) or servicer, the payment should be deductible when paid. Just because a lender requires that certain obligations be paid from the loan, these obligations are never the obligation of the lender/servicer unless title has been transferred to either the lender or the servicer. This is simply a case of a mandated payment agent. Further deductions delayed from a year where they can be deducted to a subsequent year could be disallowed in audit because they are not taken in the year of rightful deduction. If the earlier is closed by the statute of limitations, where there is question one is generally wiser to take the deduction in the earlier tax year.

So what if anything is the difference between MIP paid for by the servicer and property charges from an involuntary fully funded LESA? It is a question of whose direct obligation the real estate tax is. In the case of MIP, the payment from the borrower to the lender is simply a reimbursement of a cost to the lender, the borrower is not a direct party to the HECM insurance contract, only the lender. Even if the borrower tried to pay MIP directly to FHA, FHA would be forced to return it since it is the obligation of the lender. All payments for MIP made by the borrower are only made to the lender.

While lengthy, I hope the explanation is clear. Again there is NO expectation that the IRS will rule on payments from LESAs. The only IRS Revenue Ruling on reverse mortgages is 1980-248. It came out almost two decades after reverse mortgages were first offered by a commercial lender back in 1961 per most authorities.

While two very credible and competent income tax advisers and their staff have concluded that the limitation found at 26 CFR 1.163-10T(c)(1) excludes interest in excess of that limitation from deduction, I respectfully disagree.

IRS legal counsel has taken a very different opinion in its Memorandum Number 201201017 (or less formal 1201017) which was released on 1/6/2012. Interest exceeding the limitation may be eligible for deduction in other categories. The Memorandum is very technical and any conclusion based on that document should be made in consultation with a competent tax adviser. Further any subsequent amendment or revocation needs thorough follow up research both now and in the future; currently there appears to be none.

The Memorandum is loaded with information that can be used for planning purposes. For assurance purposes, readers may want to seek an IRS Private Letter Ruling as to specific facts and circumstances.

You will find the Memorandum at: https://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-wd/1201017.pdf

Most people believe that the interest paid amount shown on their 2016 Form 1098 is their home interest deduction. Even most tax advisers will say the same. The fact is when given a Form 1098, I used to tell my staff: “OK we are at the starting gate and hopefully there will be no complexities but the home mortgage interest deduction is one of the most difficult areas of tax law.” My sentiment in that regard when looking at reverse mortgages has only grown.

There are three types of LESAs. Mr. Kitces only focuses on real estate taxes paid from an involuntary fully funded LESA.

As to all LESAs, they are simply a set aside of loan proceeds which do not accrue interest or MIP until they are paid to their respective payees and only apply to HECMs. This is very different from an escrow where funds are committed to a fiduciary who holds cash until payments are due. As to an escrow, the bad thing for the borrower is the payment to the fiduciary is a payout of proceeds accruing interest and MIP no matter when payments are made to respective payees. That is why HUD sanctions set asides over escrows.

The difference in the payout mechanics between a mandatory fully funded LESA and a partially funded LESA is that in a partially funded LESA, all payouts are made to the borrower who is then responsible for paying all property charges on time and in full. Thus in a partially funded LESA, there is no income tax reason why the real taxes are not deductible in the tax year paid.

With the mandatory fully funded LESA, Mr. Kitces concludes that “still, though, there is no definitive tax guidance to clarify the treatment, and more clearly distinguish why an increase in reverse mortgage debt balance for interest is not a deductible ‘payment’ while a similar increase in the debt balance for a payment of real estate taxes is a deductible ‘payment’.” Since a reverse mortgage is nothing more than a nonrecourse mortgage with special features for its borrowers, there appear to be no grounds for saying the payment even though made from the mortgage is not deductible from an income tax perspective. The premise for this conclusion is that 1) the obligation is that of the borrower, not the lender, 2) the payer (servicer/lender) is an agent of the borrower as to LESA payments, and 3) the payer is an unrelated third party to the payee.

The voluntary fully funded LESA is exactly the same as the involuntary fully funded LESA except that the lender is not required to create a LESA under financial assessment but the borrower wants a LESA to make property charges in his/her behalf. Here the agency relationship clearly stands out and the only possible question is the one raised by Mr. Kitces in the quotation above which I do not believe is germane in this context. Until the IRS says otherwise, it would seem based on the statute of limitations and the IRS never issuing Revenue Ruling guidance on reverse mortgages at any time other than once in 1980, 19 years after the first mortgage was closed and 10 years before HUD closed the first HECM that the best course of action would be to take the deduction for real estate taxes in the tax year paid from the LESA rather than the tax year that the lender is reimbursed by the borrower for the payment.

Finally, as to MIP, the application is much different since the obligation is that of the lender, not the borrower. The borrower is simply reimbursing the lender for lender’s loan cost. As to evidence as to the liability for MIP, it cannot be directly paid by the borrower and there is no direct contract for insurance between the borrower and FHA. FHA only directly approves mortgagees, not borrowers. For cash basis taxpayers, the deduction can only be made in the tax year(s) that payment is actually received by the lender and is allocable to MIP.

The tax positions taken above are not advice to taxpayers but rather a general discussion and presentation of differing views on tax issues related to reverse mortgages.

can a homeowner using part of her home for rental depreciate the home (proportionately of course) if they have a reverse mortgage?

Great blog on this topic, It has a lot of information about REVERSE MORTGAGE SERVICES but if you want more details so please visit my blog-REVERSE MORTGAGE SERVICES

Mango Credit short-term first mortgage loans are flexible, require minimal documentation and are usually approved within days. We also accept applications from borrowers with affected credit history.