Executive Summary

A growing base of research shows that even though money itself is fungible, the way we think about our various money assets is not; instead, we tend to “mentally account” for money into various buckets of current income, current assets, and (assets for) future income. The fact that we tend to categorize our income and assets into various buckets helps to explain the popularity of so-called “bucketing strategies” for retirement income, whether segmented by time (short, intermediate, and long-term needs) or type of spending (essential vs discretionary needs).

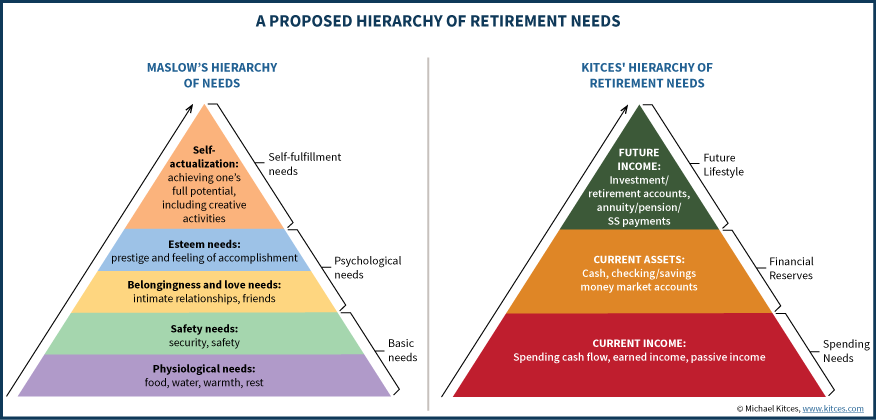

However, the research also suggests that the way we mentally account for income and assets also has an intrinsic hierarchy of priorities – first, we need to cover our current income needs, then our current assets, and finally our savings towards future income needs (ideally, with some potential for further upside and the possibility that our future income could continue to improve over time).

The significance of this “hierarchy of retirement needs” is that it helps to explain why some types of retirement income strategies like annuitization are very unpopular (despite the fact that retirees routinely state their biggest fear is outliving their retirement assets and annuitization can guarantee that will never happen), while others are used far more often even if their current guarantees are inferior to available alternatives (e.g., most guaranteed living benefit riders on today’s variable annuities).

However, perhaps the biggest caveat to the hierarchy of retirement needs is that if retirees must satisfy a desire for current income, and future income, and have liquid current assets available, they may actually feel compelled to save more for retirement than they actually need (even if there is no desire to leave a legacy behind). After all, it “should” be sufficient to just save for future and current income, without a separately holding of liquid assets; nonetheless, recent research finds that the amount of “cash on hand” (or at least, liquid bank holdings) a person has is directly (and positively) related to their self-reported well-being and life satisfaction, even if they didn’t have a financial need for it. Nonetheless, if the need for future income cannot be achieved until the need for current assets has been mentally satisfied first, retirees may continue to feel constrained by not having enough – even if they do – and/or to choose retirement income solutions that are mechanically inferior but psychologically more satisfying to our hierarchy of retirement needs!

Mental Accounting Buckets And The Hierarchy Of Retirement Needs

Various types of “bucketing strategies” have long been popular as a way to both illustrate and implement various retirement income strategies.

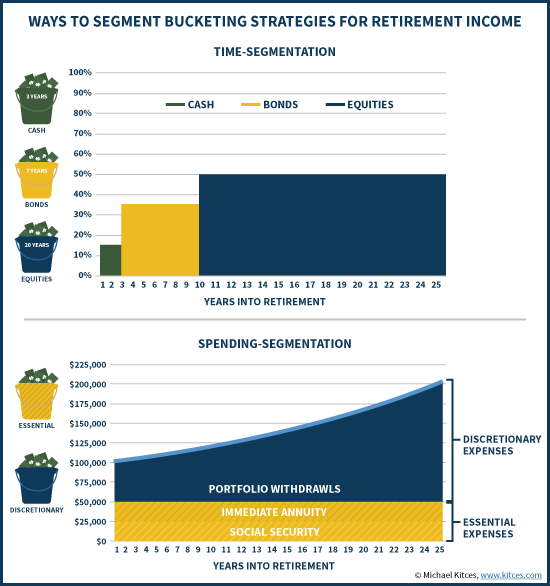

The classic “time segmentation” strategy typically divides retirement assets into three buckets – a short-term bucket to cover the next few years of spending (invested in cash), an intermediate-term bucket to cover the subsequent 5-10 years of spending (in bonds), and a long-term bucket to cover spending beyond a 10-year time horizon (invested into equities). Notably, such bucketing strategies don’t necessarily produce a materially different asset allocation than a classic diversified balanced portfolio; nonetheless, for an investor who might have a 60/30/10 stock/bond/cash portfolio anyway, it seems to be far easier for most retirees to conceptualize.

An alternative version of bucketing is to segment spending longitudinally over time, dividing long-term expenditures into “essential” expenses (the food/clothing/shelter kind of expenses you really can’t afford to outlive), and “discretionary” expenses (the ones that we want, but don’t need to survive, and can be more flexible about). Once expenses have been separated (which can be a challenge unto itself!), assets can be allocated to appropriately match the buckets; for instance, the essential expenses might be paired with Social Security and lifetime immediate annuitization, while the discretionary expenses can be funded with a diversified portfolio.

In the financial planning context, these bucketing strategies are often used as a means to help retirees get more comfortable with the impact of market volatility on retirement assets, by deliberately tying retirement accounts to either distant future retirement income needs (the time-segmentation strategy), or the more flexible retirement income needs (the spending-segmentation strategy).

More generally, though, these strategies appear to “work” because they align reasonably well with how our brains appear to engage in “mental accounting”, turning otherwise fungible assets into separately accounted buckets. Although the research suggests that mental accounting doesn’t necessarily always tie buckets directly to particular goals; instead, Shefrin and Thaler have found, in looking at the available research, that consumers most typically account for their wealth in three separate buckets: current income, current assets, and (assets to support) future income.

These mental accounts matter because, even if the actual investment accounts are otherwise similar and the money is fungible, consumers react differently depending on where they feel the “squeeze” (or the wealth) as their situation changes over time. Thus, for instance, a household that feels less wealthy is most likely to constrain their current income to get back on track (and focus the blame for their shortfall on their latest expenditures). And a household that is otherwise wealthy in net worth may still feel “poor” and be unhappy if it doesn’t have a reasonable amount of liquid cash on hand (even if they don’t need it).

Perhaps the most significant distinction of having these mental account buckets, though, is that because of their implicit prioritization – where current income matters more than current assets, which matters more than future income – it’s difficult to be satisfied with the status of the longer-term buckets until the nearer-term ones are satisfied. Or viewed another way, just as Maslow found that people have a motivational hierarchy of needs that must be satisfied in a certain order – for physiological and safety needs first, then psychological needs (e.g., belongingness, love, and esteem), and finally self-fulfillment needs – so too does the retiree appear to have a hierarchy of retirement needs that must be satisfied in the proper sequence.

And as it turns out, this hierarchy of retirement needs also reveals a lot about our actual preferences for various retirement strategies!

The Value Of Cash On Hand – The Conflict Of Cash And Annuitization

It’s long been observed that a prospective retiree’s number one concern is the potential that he/she won’t have enough money to afford retirement and/or will outlive available retirement assets and go broke. In essence, it’s the fear that the “future income” bucket of the retirement needs hierarchy won’t be satisfied. Yet the most straightforward solution to this fear – buying a lifetime immediate annuity at retirement – is rarely implemented, with immediate annuity sales continuing to hover at barely $2B every quarter, which is barely more than 1% of total annuity sales every quarter, and an even more miniscule proportion of total retirement assets.

Yet in the context of the research on mental accounting and the hierarchy of retirement needs, this is easily explained: even if we fear a shortfall of future income, we’re not willing to give up the liquidity of current assets to secure it, because having sufficient current assets is a required foundation first. In other words, even if immediate annuitization solves the “future income” need, and even if we can afford to do it, we’re still not willing to undermine the lower levels of the hierarchy to satisfy the top, because the hierarchy must be fulfilled in order. Or viewed another way, it’s not actually a “fear of outliving money” but “a fear of outliving the money that’s available after having enough liquid cash on hand (and income to pay current bills)” instead.

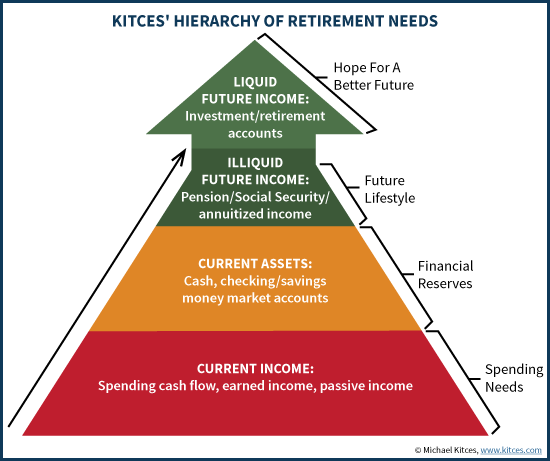

Accordingly, it’s not very surprising to find that to the extent that retirees do choose annuitization, they strongly prefer partial annuitization options to an all-or-none strategy – because it has less of an impact on the “current assets” tier of the hierarchy. Similarly, the retirement needs hierarchy and the fact that it’s necessary to have liquid current assets before committing to future-income assets helps to explain the popularity of variable annuities with guaranteed living withdrawal benefits as well – generally, the actual future-income guarantee is far superior with a pure immediate annuity than with a GLWB, but the variable-annuity-with-GLWB strategy is a more liquid version, helping to satisfy the desire for current assets. Notably, this suggests that even within the “future income” tier of the hierarchy, consumers appear to be making some distinction between allocations to “liquid” future-income sources, and “illiquid” versions (that are more guaranteed, but again at the cost of being less liquid).

The “As Good As It Gets” Problem With Annuitization And Retirement Income Guarantees

Another challenge emerging in the research on retirement income is that ultimately, it appears retirees don’t just want to have future income in retirement to satisfy their needs… they want the potential for an increasing standard of living over time, too.

In other words, it’s not enough to say “here’s a strategy to guarantee your retirement income” if it’s implicitly paired with the outcome “but this is as good as it gets”. Notably, this is distinct from a retiree who may have an explicit “legacy” goal to leave assets to heirs; in fact, the whole point is that even those who don’t want to leave assets to heirs may still refuse to annuitize their assets because of the lack of personal upside potential.

Of course, the most straightforward way to resolve this issue is to purchase a rising stream of guaranteed income, such as with an inflation-adjusting immediate annuity. Yet, in practice, inflation-adjusting immediate annuities are even less popular than traditional fixed immediate annuities. Though again, in the context of the hierarchy of retirement needs, this too makes sense: because most households have limited assets, spending the same available dollar amount on an inflation-adjusted immediate annuity will result in a lower starting payment (that increases later with inflation)… but the requirement to take a lower starting payment now causes a deficit in the tier of “current income” needs!

On the other hand, this again helps to explain the popularity of the GLWB annuity, or more generally various “floor-with-upside” retirement income strategies – because the floor helps to secure current and future income, the upside satisfies the “as good as it gets” syndrome, and the liquidity (usually associated with the investments that produce the upside potential) satisfies the need for current assets. Even if, ironically, the cumulative outcome may be an inferior retirement income guarantee!

The Hierarchy Of Retirement Needs And The Conflict Of Behavioral Biases And Reality

One of the fundamental challenges that the hierarchy of retirement needs illustrates is that retirees may have a demand for more retirement income and assets than they actually need.

Because in theory, retirement income needs can be fully satisfied with some allocation to current and future income needs. However, the research on mental accounting suggests that people typically have a “current assets” bucket as well, and that they may not be happy if it is depleted, even if it is not needed; one study found that having “cash on hand” (e.g., a liquid checking/savings account balance) was directly correlated with life satisfaction, even after controlling for investments, total spending, and indebtedness (suggesting that it wasn’t a need for cash, but simply the satisfaction of having it)!

Yet, if retirees want to have everything they need for retirement income and additional liquid assets, they will cumulatively want more than they actually need! And the situation is further exacerbated by the “as good as it gets” syndrome, and the desire to not only secure future income in retirement, but a desire for a rising future income in retirement, even though the research finds that retiree spending actually declines with age. In other words, even though we probably need less in assets to cover declining future income needs, we want even more to satisfy a desire for upside potential even if we won’t likely end up needing or using it.

A key distinction, though, is that the hierarchy of retirement needs suggests that retirees will be unwilling to convert the bulk of their assets to (illiquid) guaranteed retirement income, even if there is no desire to leave a legacy, but simply due to the “irrational” desire to have current and future income and liquidity and a potential for income upside (even if may never be spent when the time comes).

More generally, though, what the hierarchy of retirement needs suggests is that any/every retirement income strategies should probably be reframed around its ability to answer all three of these core questions for the prospective retiree:

1) Where does my current income come from?

2) Do I have a reasonable (albeit even irrationally sized) base of liquid current assets?

3) How am I funding or securing my future income, in a manner that can still grow?

And in the context of financial planners in particular, it’s crucial to remember that while we most commonly focus on #3 for the long run, the client may not be satisfied with the result until you also resolve their needs for #1 and #2, first – because the hierarchy of retirement needs must be satisfied in order!

So what do you think? Is there a hierarchy of retirement needs? Does this hierarchy help explain some seemingly irrational consumer preferences? Must we resolve the current income and liquid current asset goals of clients before they'll be satisfied addressing future income? Please share your thoughts in the comments below!

While we certainly need to start the process of making retirement investing and savings evidence-based and use peer-reviewed facts – like any other profession – this article is a hodge podge and pretty much none of the ideas are based in tindependent or objective studies, facts or data. That’s OK, have to start somewhere.

There are too many unsupported statements and claims to question. For example this claim ” the most straightforward way to resolve this issue is to purchase a rising stream of guaranteed income, such as with an inflation-adjusting immediate annuity.” OK, where is there any independent experimental study, data or set of facts to support this claim!? If a doctor, or any other professional, made this kind of claim without facts – they would be sued.

Finally, “Without data, you are just promoting your personal opinions.”

As you note, “have to start somewhere”. The point here is to set forth a starting theoretical framework to the issues. There are ample testable hypotheses that can be evaluated going forward. (And theorize-then-test is ultimately how many/most models are developed and affirmed.)

In terms of the particular statement you complained about, though, I have to admit I’m puzzled why you would challenge it. The context was “people who want to buy annuities often object because the payments are level.” To say “the solution to people complaining about level non-rising payments is to use a version that has rising payments” seems… not controversial, to say the least. 🙂 We can certainly debate about whether there are OTHER constraints as well – in fact, I point out immediately following that rising-payment annuities actually have LOWER sales volume than level-payment annuities, which clearly implies there are more issues at stake. Still, the idea that “the way to solve a complaint that annuities have level payments which don’t rise, is to buy a version where the payments do rise” is a simple statement of logic? 🙂

But yes, creating a new model that hasn’t yet been tested is almost by definition going to be a personal opinion until it’s validated. When Markowitz first proposed Modern Portfolio Theory, it was just his personal opinion, too. The validation came later. Of course, many models are never validated. But disproving them still often teaches us much, and there’s value to hypothesizing testable models that are ultimately invalidated by data, too.

We have to start somewhere. 🙂

– Michael

Brain,

I’m all about data but I don’t believe the statement you pointed out is a good example of something that requires additional support. It’s fairly obvious without any additional support that purchasing “a rising stream of guaranteed income” is the most “straightforward” (easiest, most obvious, least complicated) way to provide for an “increasing standard of living” that some retirees desire. In this case, sourcing peer-reviewed data/research simply isn’t required to support the “most straightforward” claim regarding inflation-adjusting immediate annuities.

Thanks and I now know I can skip reading your comments.

Coincidentally I met with a retiree client yesterday who said “I like having money in my wallet (and in the bank). I grew up in a poor family and doing so makes me feel good”. He isn’t a big spender and not a sophisticated investor. A few months earlier I met with a very sophisticated bank executive client transitioning into semi-retirement. He showed me an elaborate diagram with a number of asset buckets and lifestyle spending requirements matched to each … he was practising what some call as “Asset Dedication”.

Both examples strongly support this article’s message and the need to at least carefully communicate how an overall mix of assets meets multiple needs – without necessarily reverting to buckets which sometimes “leak” to much money into cash/bonds.

As for annuities, I suspect the answers there are more complex. Some are also convinced rightly or wrongly they can generate returns, longevity aside. In the past I think this was wrong about 1/3rd to 1/2 the time. However for now with worldwide money printing – bond buying, the price of annuities have also been indirectly manipulated to record highs (yields down to record lows) so I think it is reasonable to question if they are good value at the moment?

Good article Michael

The principle is very simple – professional statements and claims need facts, data and independent evidence to support them. The sources of those facts and evidence need to be disclosed and transparent, as do conflicts of interest. In other professions, claims that are not supported by independent facts are either unethical or illegal, or both. Think of doctors, accountants, lawyers, engineers, etc.

Now sales people are not held to professional standards of proof and ethics.

Also, with the statement – “To say “the solution to people complaining about level non-rising payments is to use a version that has rising payments” seems… not controversial, to say the least. 🙂 ” The question is also simple – how is the truth and value of this statement measured? Over what period of time?

There are many other problems with the ideas and claims in this article but let’s stick with one example.

Good article Michael. As a proponent of the “essential income” and “discretionary income” method of income segregation and having done hundreds of client analysis on this basis over the years, I disagree with your comment that identifying the components of each type income segregation is difficult, it is just a question of how the client data is collected and analyzed. As to the “annuitization” question and GLWB vs SPIA, it is clear that the SPIA route can produce more income than does a GLWB, but from a “behavioral standpoint,” which is really emotion, the GLWB method provides the client with the comfort that their money remains “theirs” (perhaps a false comfort because access beyond the GLWB guarantee reduces the guaranteed income amount going forward). As for increasing income over time, whether it be the GLWB or the SPIA method, I think the reason level payments remain more popular is that for a given amount of premium, an increasing income actuarily requires a lower starting income level. Personally, my preference is to use a level payment from a GLWB (or SPIA), with risk assets (due to higher growth potential and liquidity) used to increase the overall income stream over time as as-needed. This is simply a math problem to calculate the required CAGR on the risk assets over time, and of course aligning that to the clients’ risk tolerance and risk capacity (thanks for that article Michael). Ultimately with many clients, this reveals that, to paraphrase the Rolling Stones, they can’t always get what they want, but they can get what they need.

Thanks for writing this.

As someone in their mid 40’s who has been thinking about retirement planning a lot over the past 2 months, this article is really helpful in understanding my own biases.

Thanks Adam! Hope it’s helpful food for thought! 🙂

– Michael

I retired 3 years ago at 63. I am not sure how I ended up on this site but I enjoyed reading your article and the comments. From a “client” perspective I have always been worried I would run out of money in retirement as I have longevity in my family. Although leaving money to my step-children would be nice it is not an investment priority. Here is how I solved my financial fears: I invested 10% of my assets in an inflation adjusted immediate annuity ($700/month) which covers my medical, dental, vision and long term care premiums. I invested 20% in a deferred fixed income annuity that will begin paying in 10 years ($2500/month when I am 74). I agonized over putting money into these annuities for a year before I did it but I needed a guarantee that I would have an income for life. I needed peace of mind to be happy. I am now considering a QLAC that will begin paying $800/month when I am 85 which I hope will help cover rising costs due to inflation since my deferred annuity will not. I am waiting to collect Social Security until I am 68 ($35,000/year). I figure my fianancial future is pretty much set so I can live off of my current assets without feeling guilty about spending some of my savings or being afraid I will run out of money. I hope this is a good plan…..

Interesting article. It really describes my 86 year old mother. A child of the depression, she is scared to death that she will run out of money, although she has a enough cash to live on for years, even more invested in real estate, and even more invested in mutual funds. I now have a better understanding of why she is so fearful.

I myself will retire in 34 months and 25 days (but who’s counting?). I’ve got multiple pensions, a 401K, multiple IRAs and I am my Mom’s only heir. I’m structuring my retirement income without considering what I might inherit. I’m not thinking in terms of buckets. I’m creating a budget to manage expenditures and inflows from all these accounts to create a slowly increasing income stream over the next 30 years. I’m looking at using an immediate annuity from some of the 401k proceeds and taking monthly distributions to lower the 401k balance so required minimum distributions don’t harm my tax situation or medicare premiums. I am not going to claim SSA until it and my pensions cover all may living expenses, and using my IRAs to fill in between retirement and when I start SSA — roughly 4 years. I first looked at a bucket strategy — just did not like picking and choosing accounts to pull from for each expense or for short term or long term expenses. I’d rather set up a long term plan and execute it across all accounts.

My concern is setting it up to maximize tax savings. The difficulty of this has only been exacerbated by all the uncertainty with the new administration and the proposals for “fixing” Social Security. Any suggestions over how to plan for distributions and annuities while maximizing taxes?

Good article. As one who agonized over just when to retire, I can appreciate how difficult it is to make these financial decisions, esp. once we reach an age when we can no longer get any “do overs”. I moved up my planned age 66 retirement to 65. I will be 67 this year, and so far, no regrets. I was an industrial buyer, and planner my working career, and I planned my finances for a year, including living off what I knew to be my retirement income, SSI & a small pension. I am fully enjoying my retirement thus far, and have no fears of outliving my financial resources. My 401K remains virtually untapped thus far, I am considering a fixed guaranteed annuity, with survivor’s benefit, as a possibility, at least for perhaps 25% of my 401K assets. Delaying retirement to maximize SSI sounds great on paper, but, it overlooks the value of the an extra year of retirement. If you live beneath your means, and owe no $$ to anyone, you always have the option of adjustments and a plan B or C if your circumstances change.

Michael, is the need to have some cash in the bank an innate human need or is it a learned “need” due to having it drilled in that one needs an emergency cash reserve. I suspect the latter is the case. If so, the next question would be, can people be retrained in retirement to do what is optimal for their new circumstances, so as not to feel compelled to keep so much cash at the ready? I’m hoping I’m going to be able to retrain when I get there to re-value having emergency cash when I have so much non-stock-invested money accessible to me in my nest egg. I have client’s who I’m trying to retrain on this very issue. We’ll see how it goes!

Kay

I just waited until I had an amount large enough so that I could live off my dividend and interest income plus a 30% buffer without using social security. Social security serves as a hedge in my case.

Michael, I think that this is a fascinating idea (hierarchy of retirement needs) that seems to explain a lot of the often ‘irrational’ behavior of retirees as well as younger people. A recent study found that even Millennials favored a guaranteed 1% return to stocks, which they perceived as risky. I think that might be in part a function of them not currently having adequate liquid assets. And since around half of Americans can’t lay their hands on a thousand dollars without selling something or going into debt, I’m sure that Millennials are in even worse shape than that.

It really seems that retirees, in particular, want to have their cake and eat it too. That explains why variable annuities are an easy sell to this group; they promise a floor as well as upside potential with at least some liquidity, even though they are, by most accounts, a ‘suboptimal’ solution, to put it mildly.

Great article — I’ve spent a lot of time on this topic and my ahah comes from approaching retirement age personally and recognizing my own emotional biases over the intellectual analysis I’ve done for years – big difference. The Principal published a white paper years ago that I may still have somewhere – it was a great analysis of the ‘bucket’ strategy having no real scientific value over a diversified asset portfolio but perhaps a great deal of emotional value because, as you say, it helps people ‘conceptualize’ they’re financial situation. you say it well.

Very well written. And one of your shorter pieces. I bet this took more than your usual amount of pre-writing organizing.