Executive Summary

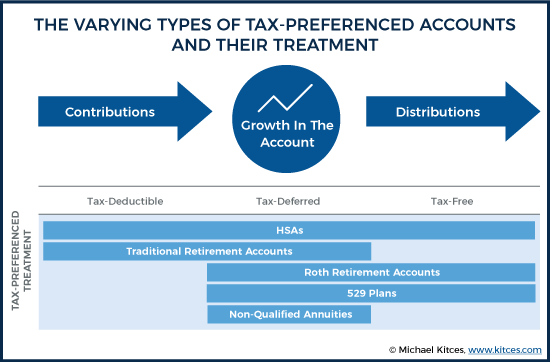

The Federal government has long incentivized saving for retirement and other financial goals by offering some combination of three types of tax preferences: tax deductibility (on contributions), tax deferral (on growth), and tax-free distributions. As long as the requirements are met, various types of accounts - traditional to Roth IRAs, and annuities to 529 plans to Health Savings Accounts - enjoy at least one tax preference, often two, and sometimes all three.

For most households, these tax-preferenced accounts simply help to encourage (and tax-subsidize) savings towards various goals, and cash-flow-constrained households allocate based on whichever goal has the greatest priority. Yet for a subset of more affluent households, where there's "enough" to cover the essential goals, suddenly a wider range of choices emerges: how best to maximize the value of various tax-preferenced accounts where it's feasible to contribute to several different types at the same time?

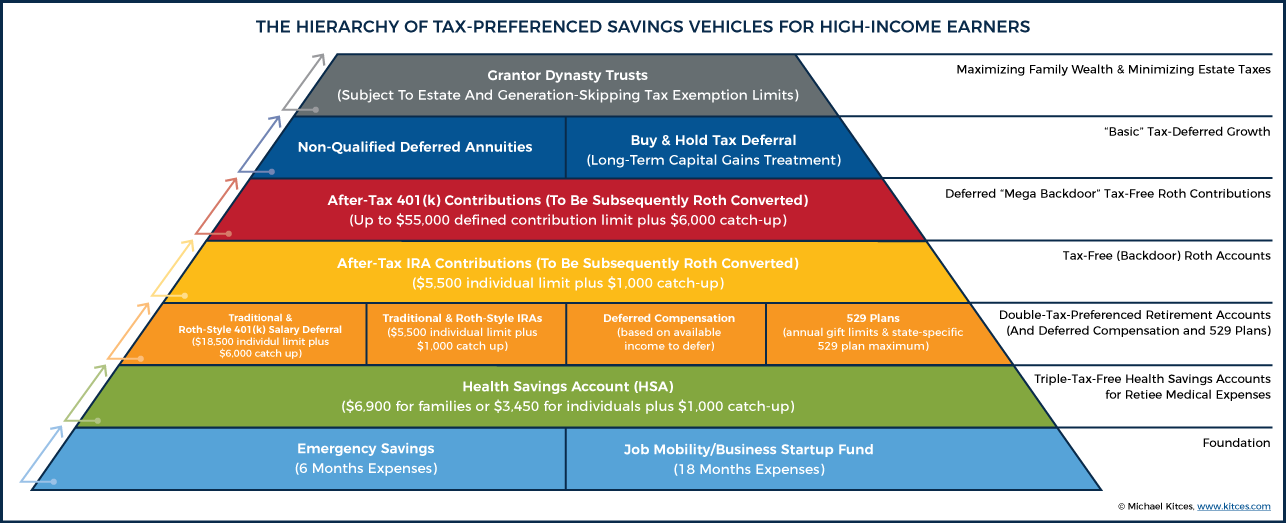

Fortunately, the fact that not all accounts have the exact same type of tax treatment means there is effectively a hierarchy of the most preferential accounts to save into first (up to the dollar/contribution limits), after which the next dollars go to the slightly less favorable accounts, and so on down the line... from triple-tax-preferenced accounts such as the Health Savings Account (tax-deductible on contribution, tax-deferred on investment growth, and tax-free at distribution for qualified medical expenses expenses), to double tax-preferenced accounts such as traditional and Roth-style IRAs, to single tax-preferenced accounts such as a non-qualified deferred annuity (which is tax-deferred only). Which in turn must be balanced against even "traditional" investment strategies of simply buying and holding in a taxable account... which itself effectively defers taxes, thanks to the fact that long-term capital gains are only taxed upon liquidation.

Notably, many of the tax preferences do come with trade-offs (such as penalties for early distribution, and rules about how the funds can be spent), but for high-income earners, those limitations simply mean it will be necessary to coordinate amongst the various tax-preferenced savings accounts at the time of liquidation (and aren't a reason to not use them in the first place).

Of course, there is still the foundational tier of savings to provide an emergency fund (and perhaps funds to promote job mobility and business startup expenses as well, which may be particularly appealing for higher income individuals), but the key point is to acknowledge that there is a hierarchy of tax-preferenced accounts – ranging from triple-tax-preferenced accounts to accounts with no tax preferences – and high-income earners can better limit their tax liabilities and maximize their growth by adhering to this hierarchy!

Choices Amongst Types of Tax-Preferenced Accounts

In an attempt to both encourage retirement savings, and provide a tax subsidy to help savers reach their retirement goals, the Federal government has created a number of different types of tax-preferenced retirement accounts over the years.

At their core, tax-preferenced retirement accounts comprise one of two types: “traditional” accounts, which provide a tax deduction for contributions (i.e., are “pre-tax” going into the account) but ultimately tax the distributions; or “Roth”-style accounts, which are not deductible when contributions are made (i.e., are funded with “after-tax” dollars) but ultimately are tax-free when distributed. And both types of accounts actually have a 3rd tax-preference component – growth inside the account is tax-deferred as well (either until it’s taxed upon distribution from a traditional account, or is received as a tax-free qualified distribution from a Roth).

In essence, this means tax-preferenced retirement accounts are really “double-tax-preferenced” – receiving both tax-deferred status on assets in the account and either a tax-deduction upfront, or tax-free distribution treatment at the end. Not unlike 529 college savings plans, which – similar to Roth-style accounts – are tax-deferred during the accumulation phase, and tax-free at distribution (but no tax deduction on contribution, at least at the Federal level).

Notably, though, some tax-preferenced savings accounts are even better. The Health Savings Account (HSA) is actually a “triple-tax-free” account, providing tax-deductible contributions upfront, tax-deferred growth, and tax-free distributions (at least for qualified expenses), as contrasted with retirement accounts that only offer two out of three. By contrast, the non-qualified annuity only offers one tier – tax-deferral, as contributions are not tax-deductible, nor are distributions tax free.

Of course, the caveat is that in order to receive more preferential treatment of any type, it’s necessary to accept additional trade-offs. Non-qualified annuities are tax-deferred in exchange for distributions being subject to a 10% early withdrawal penalty (in addition to being taxable); traditional pre-tax retirement accounts also face a potential 10% early withdrawal penalty, and have contribution limits to constrain the amount of upfront tax deductions available. And tax-free accounts like Roth retirement accounts, 529 plans, and HSAs have additional requirements about how the money is used at the time of distribution, in order to preserve their tax-free-distribution treatment.

For many or even most people, the selection of which type(s) of tax-preferenced accounts to use is simply based on whatever goals they are pursuing – whether it’s paying for medical expenses and health insurance deductibles (via an HSA), sending kids to college (funding a 529 plan), or saving for retirement (with various traditional and Roth retirement accounts). To the extent that dollars are limited, it’s an exercise in building up an initial emergency reserve, and then allocating scarce resources to whatever goals have the greatest current priority, while hoping to make the rest up with future savings (and future income increases) down the road.

For some, though, they are high-income enough that “basic” needs like an emergency fund, sending kids to college, and covering the medical expenses are set. For such households – who might be earning $300,000 or more – it’s all about saving for retirement (saving more/faster/better to retire earlier), building family wealth beyond, and maximizing the economic value of the dollars being saved along the way. In other words, for high-income individuals, the question is not if a certain type of account can or will be used, but more of a question of how to prioritize amongst the myriad of vehicles when the core question is “there is enough money, we just want to maximize what we can to grow it faster”?

In essence, high-income earners who can save more than enough to cover “traditional” retirement accounts like IRAs and 401(k)s, need to develop a hierarchy of how to save the “excess” dollars that come next!

Hierarchy Of Savings Vehicles For High-Income Earners

Relative to the alternative of simply keeping available dollars “liquid” in a bank account or a traditional (taxable) investment account, the appeal of tax-preferenced accounts is, by definition, their tax preferences. Which means, not surprisingly, the optimal approach amounts to maximizing the “best”-preferenced accounts first, and as those various contribution limits, “spilling over” the next/additional savings to the next best tier on the hierarchy.

Tier 1: Triple-Tax-Free Health Savings Accounts For Retiree Medical Expenses

In this context, the first and best place to commit to long-term tax-preferenced savings for high-income individuals is a Health Savings Account (HSA), the only triple-tax-free option available that provides a tax-deduction upfront, tax-deferred growth, and tax-free distributions, for up to $3,450 for individuals or $6,900 for families (plus a $1,000 catch-up contribution). Of course, the purpose of HSA dollars – to qualify for tax-free treatment – is limited to medical-related expenses, but ostensibly anyone/everyone anticipates at least some medical expenses in the future.

In fact, the key to maximizing the HSA as a high-income savings account is to pay all actual medical expenses out of pocket, while also contributing to the HSA to cover future medical expenses. Because the reality is that it’s impossible to leverage the tax-deferred-and-tax-free benefits of an HSA until and unless it’s given time to grow tax-deferred and tax-free in the first place.

Which means, in essence, the HSA would be treated as a supplemental retirement savings account, specifically earmarked to provide for (tax-free distributions for) medical expenses in retirement, where it can fund everything from actual medical expenses (anything otherwise deductible as a medical expense under IRC Section 213, including most long-term care expenses, co-pays, and deductibles under Medicare in retirement), to long-term care insurance premiums (up to the age-based LTC premium limits), and even Medicare Part B and Part D premiums (though not Medigap supplemental insurance premiums).

Of course, the caveat to having an HSA is that it’s only permitted for those who have a high-deductible health plan (HDHP) in the first place (with minimum deductibles of $1,350 for individuals and $2,700 for families, and maximum out-of-pocket costs as high as $6,650 for individuals and $13,300 for families). On the other hand, arguably most high-income households should have a high-deductible plan anyway, simply because they have the financial wherewithal to self-insure a larger deductible, and have the cash flow available to cover the cost of the deductible (on top of making an HSA contribution) to begin with.

Tier 2: Double-Tax-Preferenced Retirement Accounts (And Deferred Compensation and 529 Plans)

After the uniquely-triple-tax-free HSA, the next tier of high-income savings are the various double-tax-preferenced retirement accounts – the traditional or Roth style accounts that are both tax-deferred on growth and either tax-deductible upfront or tax-free on distributions at the end.

Notably, most high-income individuals, who feel the pressure and impact of the top tax brackets, tend to prefer Roth-style accounts, to eliminate that tax bite on growth going forward, either by making contributions to a Roth 401(k), and/or via a backdoor Roth IRA contribution.

Ironically, though, for most high-income individuals, it’s actually better to contribute to a traditional account rather than a Roth-style account, in order to get the upfront tax deduction at those current high/top tax rates. Because the reality is that a Roth retirement account only “wins” relative to a traditional account if the tax rates at the time of distribution are higher (or at least equal to) the tax rates at the time of contribution… and it’s difficult to have higher future tax rates for those who are already in the top tax bracket, as even very affluent individuals have trouble reaching the $600k/year of ORDINARY income, AFTER deductions, it takes for a married couple in retirement to hit the top tax bracket (or $500k/year for individuals), and despite fears of rising future tax rates given current budget deficits, the trend in Washington is towards tax reform that could actually lower the top tax bracket (while also trimming deductions). In other words, the Roth-style account really only “wins” for those who are in not just the top tax bracket now, but the top bracket for life (often translating to $15M+ of net worth or more)… and assuming there’s no tax reform along the way. For the rest, even at high income levels, it’s better to get the tax deduction now, at top rates, and for those who want a tax-free Roth in the long run, do partial Roth conversions later after the wage/employment income ends, and the tax bracket drops.

In practice, this means not contributing to a backdoor Roth IRA or Roth 401(k), and saving instead the $5,500 maximum (or $6,500 for those over age 50) into traditional pre-tax IRAs if possible (very high-income individuals can only do so if they are not already an active participant in an employer retirement plan, nor their spouse), and otherwise maximizing contributions up to the $18,500 limit (or $24,500 with catch-up contributions for those over age 50) to a pre-tax 401(k) plan.

For those who are high-income and either own their own businesses, or at least are sole proprietors filing a Schedule C, there are even more savings opportunities by creating a retirement plan for the business, where total contributions to a 401(k)-salary-deferral-plus-profit-sharing plan in the aggregate can be as high as $55,000 (effectively allowing as much as another $36,500 in contributions above the $18,500 401(k) contribution limit alone for those earning at least $270,000/year, in addition to another $6,000 in catch-up contributions). Even higher contributions may be feasible for those in their 50s or 60s who want to set up a supplemental defined benefit plan as well. Although notably, those business owners with employees will have to make contributions to other employees as well, which may reduce the value of making additional profit-sharing or defined benefit plan contributions, making alternatives like a deferred compensation plan more appealing instead (and often the only option beyond 401(k) salary deferrals for high-income employees who don’t otherwise own and control the business).

In addition, for those who are saving for children’s college education, it is appealing to leverage 529 college savings plans at this tier, to maximize the opportunity for tax-free growth, especially for younger children who have a decade or more to benefit from tax-deferred compounding growth. In fact, for those who anticipate “more than enough” wealth to cover the family’s needs, additional funding into a 529 plan, up to the 529 plan’s maximum account limits (determined based on the state), is compelling, as the plan beneficiary can always be changed in the future to other family members (e.g., future grandchildren, for whom the plan may have grown and compounded tax-free for decades!).

Tier 3: Tax-Free (Backdoor) Roth Accounts

As noted earlier, most high-income individuals should actually maximize pre-tax retirement accounts first – and at best, only contribute to Roth-style accounts later via a (partial) Roth conversion. The caveat, however, is that high-income individuals who aren’t business owners will be stuck with “just” $18,500 (plus catch-up contributions) of 401(k) contributions, and at that point may not be able to make a pre-tax contribution to a traditional retirement account at all (due to the income limits for those who are active participants in an employer retirement plan).

In such situations, “just” making an after-tax contribution to a non-deductible IRA is still a viable option, and at least helps to avoid the 3.8% Medicare surtax on investment growth, but is otherwise only a “single-tax-preferenced” account (tax-deferred growth, but no deduction on contribution, nor tax-free at distribution). Which makes it very appealing to subsequently convert those non-deductible IRA contributions into a backdoor Roth contribution instead (as for high-income individuals, direct Roth contributions are not feasible due to the Roth income limits).

Fortunately, there are no income limits to doing a backdoor Roth contribution, beyond recognizing that it should come secondary to maximizing an HSA and the $18,500 pre-tax contribution limit to a 401(k) plan (and any other pre-tax options available via deferred compensation or a small business retirement plan). However, it is important to navigate around the IRA aggregation rule that can cause non-deductible IRA contributions to become partially taxable (unless the other dollars are first rolled into a separate 401(k) plan), and to wait a reasonable time period (e.g., 12 months) between the non-deductible IRA contribution and subsequent conversion (to avoid the step transaction doctrine). Single-earner-high-income couples should bear in mind that a non-working spouse can make non-deductible IRA contributions that are subsequently converted to a Roth as well under the Spousal IRA rules.

Notably, those who are not an active participant in an employer retirement plan can simply make a pre-tax deductible IRA contribution, making this backdoor Roth IRA contribution tier a moot point (as the IRA contribution limit will have already been satisfied in the preceding tier).

Tier 4: Deferred “Mega Backdoor” Tax-Free Roth Contributions

After the backdoor Roth contribution has been maximized, the next option is a “deferred Roth contribution”, also sometimes called the “mega-backdoor Roth” contribution.

Popularized after it was explicitly permitted under IRS Notice 2014-54, the mega-backdoor Roth is accomplished by making after-tax contributions to a 401(k) plan – above and beyond the traditional salary deferral that can be done pre-tax – which are later converted to a Roth (once the money can be rolled out of the plan, either at retirement, or as an in-service distribution where permitted).

The good news of the mega-backdoor Roth contribution is that, as the colloquial name implies, the contribution limits are significantly higher – starting above the $18,500 pre-tax salary deferral limit, and extending all the way up to the $55,000 contribution limit for total dollars into any defined contribution plan, for a potential maximum mega-backdoor-Roth contribution as high as $36,500.

However, there are several caveats to the mega-backdoor-Roth, which reduce its appeal relative to the preceding tiers. The biggest is that while IRS Notice 2014-54 permitted after-tax contributions to be converted to a Roth account (while any taxable growth is simply rolled over to a traditional IRA), the tax-free Roth status does not begin until the dollars are actually converted to a Roth – which means getting them out of the employer retirement plan. As a result, the mega-backdoor Roth in practice is often a “Deferred Roth” contribution, which doesn’t come until either the employee retires (or at least separates from service), unless the plan happens to allow in-service distributions. In addition, the employer retirement plan must allow after-tax contributions in the first place, which not all do.

In addition, the $55,000 limit for all contributions into a defined contribution plan includes both the $18,500 salary deferral limit, after-tax contributions, and any profit-sharing or other employer pre-tax contributions. As a result, employers that make profit-sharing or salary matching contributions will reduce the remaining availability of making after-tax contributions (albeit because they were already more favorable as pre-tax employer contributions!), and business owners and especially sole proprietors who leverage the defined contribution rules to contribute the maximum pre-tax (all the way up to $55,000) will fully crowd out their after-tax mega-backdoor Roth contribution.

It’s also worth noting that there is at least some risk that, during the time period between the after-tax contribution and the subsequent Roth conversion (or when it becomes possible to take a distribution and convert it to a Roth), that Congress will change the rules to eliminate the ability to convert after-tax dollars (a “loophole closer” that has already been proposed once in the past). Nonetheless, the “worst case” scenario is simply that the after-tax contributions will grow tax-deferred – similar to other non-deductible contributions on the next tier down – which means as long as other higher-tier savings options have been maximized first, the worst case scenario is simply that the benefits of this Tier consolidate into the next.

Tier 5: “Basic” Tax-Deferred Growth

The next tier of high-income savings vehicles are those that do not provide any upfront tax deduction nor any kind of tax-free distributions, but do allow for tax-deferred growth along the way.

The most common vehicle at this tier is the non-qualified deferred annuity, which when held outside of a retirement account provides tax-deferred growth. The biggest caveat of the non-qualified annuity is that as an annuity, which provides at least some retirement income guarantees, there will be an additional cost for the annuity guarantees and the “tax deferral wrapper”. However, the good news is that for high-income individuals who just want tax-deferral, there are a growing number of “Investment-Only Variable Annuity” (IOVA) contracts that have very few guarantees, which enables them to have a very low cost. And when the costs are low enough – sometimes 0.50%/year or even lower – it can be very worthwhile to “pay” the annuity costs just to get the tax-deferral treatment, especially for tax-inefficient high-return (i.e., for growth-oriented investments) investments otherwise being taxed at top tax brackets.

Classically, permanent cash value life insurance has also been used as a tax deferral vehicle – similarly absorbing the costs of not-necessarily-needed life insurance death benefits just to access the tax-deferred growth treatment available to cash value life insurance, where the growth is subsequently borrowed against to avoid triggering tax consequences on distribution. The caveat, though, is that it’s impossible to actually borrow and use “all” of the cash value or the policy risks lapsing and causing a substantial adverse tax consequence, and in today’s environment, low-cost annuities are often inexpensive enough that the cash value life insurance usually doesn’t make sense as a pure tax-deferral strategy (and at best must be carefully designed to allow for a maximal internal rate of return to make it competitive to available alternatives). As a result, cash value life insurance is more commonly used for at least those who have a blended need for savings and a death benefit, for ultra-high-net-worth investors who can access lower cost private placement life insurance policies (albeit with a higher upfront cost that still makes them impractical for most), or simply those who want to maximize the tax-free death benefit of the life insurance and don’t actually care about using the cash value itself.

It’s also notable that the good old-fashioned “taxable brokerage account” can also effectively be a tax-deferred growth vehicle, at least for long-term growth assets… because capital gains themselves aren’t taxable until sold! In fact, a zero-dividend growth stock that is held until liquidation gets the same “tax-deferral” treatment as an annuity, but without the cost of the annuity wrapper, and gets preferential long-term capital gains rates at distribution (while an annuity is taxed as ordinary income upon withdrawal). Unfortunately, investments with a non-trivial dividend and even a modest level of ongoing turnover can experience enough tax drag to make them less appealing to hold in taxable accounts; nonetheless, the point remains that for buy-and-hold investors of long-term growth stocks (or certain tax-managed mutual funds, or even real estate with its preferential depreciation rules), sometimes it’s not actually necessary to find an alternative on this tier of savings vehicles, as the treatment of capital gains itself is tax-deferred (as long as there’s a plan for how to unwind the cumulative capital gains when the time comes!)!

Tier 6: Maximizing Family Wealth And Minimizing Estate Taxes With (Grantor) Dynasty Trusts

For those who truly have earned and saved “more than enough” and want to further maximize family tax-preferenced growth with additional savings, the next tier of savings vehicle is a (grantor) dynasty trust.

The concept of a dynasty trust is simply a trust that is designed to last for multiple generations – typically done by utilizing some or all of both the lifetime gift tax exemption and the generation-skipping-tax exemption to allow assets placing into the trust to avoid future estate taxes (for one or several generations).

Notably, dynasty trusts are not necessarily an income tax savings vehicle; in fact, trusts face a top tax bracket of 37% at just $12,500 of taxable income, making such “compressed” trust tax rates worse (or at best, no better) than what high-income households already face.

Instead, the tax-savings-appeal of a dynasty trust is actually to structure it as a grantor trust, which makes the income tax consequences of the trust remain as the tax consequences of the original grantor, even after the dollars have been gifted/transferred into the trust. Which means that the grantor ends up in the exact same situation – paying taxes on any dollars/growth in the trust that he/she would have paid by just keeping the money and investing it in the first place. The appeal of this approach, though, is that it means the grantor has the opportunity to use dollars in his/her estate to pay the income tax bill, for a trust that is growing outside of his/her estate (permissible under Revenue Ruling 2004-64). Which means that while the grantor themselves ends up in the same position, the dynasty trust effectively grows “tax-free” – both income-tax-free (because it’s paid by the grantor instead) and estate-tax-free (since it’s a dynasty trust) – which can accelerate the tax-free growth of the dollars for future generations’ family wealth.

A Word About Taxable Savings, Emergency Funds, Job Mobility, and Entrepreneurialism

Notwithstanding these six tiers of tax-preferenced savings vehicles for high-income earners, it’s important to recognize that the most important foundational tier is to simply have a healthy emergency fund (and disability insurance!). Because even as a high income earner, the income can end, and being compelled to liquidate tax-preferenced accounts and losing those benefits (or even paying 10% penalties) because there wasn’t enough liquidity can leave the household worse off than having just skipped tax-preferenced accounts altogether. Not to mention the growing base of research that shows having reasonable cash on hand just increases our happiness anyway!

And arguably, for high-income households in particular, the ideal should be not just the classic 6 months of emergency savings, but another 18 months for “job mobility” and future business/career opportunities as well. Because, unfortunately, high-income jobs often become binding and difficult to sustain if there’s a need/reason to switch jobs. Which in turn risks leaving the individual stuck in a(n admittedly high-income) dead-end career, or simply stuck in a job that is no longer enjoyable (with no economically feasible way to transition to a better one because all of the cash is tied up in tax-preferenced accounts!). There’s nothing more freeing about making good career decisions than knowing you have more than enough saved that you can take career risks and still have an ample cushion to fall back on.

In other words, it’s important not to let the tax tail wag the investment dog and miss out on the greatest wealth creation opportunity for those who are still working… which is the opportunity to find a job (or start a business) with even better earnings, which can produce many multiples of wealth creation from “just” benefitting from tax-preferenced growth on investment savings. In other words, the best tax-deferred savings vehicle, and compounding wealth opportunity, is often investing in your human capital.

Arguably, this is especially true for anyone who has any inclination to create a businesses, as businesses themselves create enterprise value that is tax-deferred (as increases in the business value aren’t taxed until the business is sold), converts ordinary income into capital gains (converting wage income into capital gains on the sale of the business value instead), and potentially has additional special tax benefits as well (under IRC Section 1202).

And so while it’s important to maximize the tax-preferenced vehicles available for high-income earners to save, don’t forget to save not only for an emergency fund first, but also a “job mobility/business start-up” fund as well, which has both tax benefits, and potentially the greatest wealth creation potential of all!

So what do you think? How do you help clients prioritize savings within the hierarchy of tax-preferenced vehicles? Where do you see individuals make the biggest prioritization mistakes in the hierarchy? Please share your thoughts in the comments below!