Executive Summary

As financial advisors, we understand that one of the most important (and difficult) things we can do for our clients is help facilitate positive behavior change. And not just change that keeps clients from doing “bad” things (like selling at a market bottom), but also change that enables them to do “good” things (like saving more for retirement).

Unfortunately, behavior change is hard, but the good news is that the difficulty of enacting behavior change also means it is one of the most valuable things we can do as financial advisors. And the human-to-human connection – and the social commitments we feel – provide some powerful incentives to enact behavior change… which means financial advisors serving as an “accountability partner” to their clients have the potential to drive more successful behavior change than what clients can do on their own.

In this guest post, Derek Tharp – our Research Associate at Kitces.com, and a Ph.D. candidate in the financial planning program at Kansas State University – analyzes some existing research in the contexts of weight loss and alcoholism to explorer the power of the human-to-human connection in holding us more accountable (than we can be to ourselves alone) to accomplish our goals and behavior our behavior.

In other words, the unique power of the human-to-human connection means clients can achieve better behavior-change outcomes with a financial advisor than they may be able to achieve by themselves or through the use of technological tools. Because when a human is involved, we often have few options for totally avoiding the unfavorable perceptions we think others may have about us if we don’t follow through on our goals… which can be highly motivating. In the case of technology, while it may provide useful behavior change reminders… we can always just turn off the technology, and feel very little guilt. But it’s far harder to just “turn off” an existing relationship with another person.

Of course, this still doesn’t mean that enacting behavior change is easy. It is very difficult, but by acknowledging the social pressure that exists within an advisor-client relationship, we can use strategies – such as setting clear action items for clients based on “SMART” criteria, and encouraging clients to leverage social forces in contexts outside of the advisor-client relationship – to can help clients improve their financial well-being. Ultimately, we human beings are herd animals, and as financial advisors we should keep that in mind as we develop strategies to help clients achieve their financial goals!

The Difficult Dynamics of Positive Behavior Change

One of the most important (and difficult) things financial advisors help do for their clients is facilitate positive behavior change. And not just change that keeps clients from doing “bad” things (like selling during a market decline), but also change that enables them to do “good” things (like saving more for retirement).

At a high level, the fundamentals of what most people need to do in order to achieve better financial outcomes (save more and spend less) are incredibly simple. Further, most people are already aware of what they must do, but that doesn’t make behavior change any easier.

Whether it is eating better, exercising more, or saving for retirement, some insidious dynamics underlie many of the situations in which we must make a change in order to improve our well-being. Namely, the cost of waiting a day is often small, while the cost of never getting started is very large.

Example. John is a recent graduate earning $50,000 per year. John would like to start saving 10% of his income, but he hasn’t gotten started yet. As John is getting accustomed to his new lifestyle, he continues to have small expenses come up that keep him from starting saving, but he plans to start saving soon.

Suppose John were to break up his annual saving goal on a daily basis. To save 10% of his gross income, he would need to save a little less than $14 per day. However, the tricky thing about saving is that the cost of waiting one more day to get started ($14) is incredibly small and will have virtually no impact on his life, while the cost of never getting started (a life of poverty in retirement) is incredibly large. John can rationally decide to wait until tomorrow to get started saving, but once tomorrow rolls around, the dynamics are exactly the same.

And even once John does get started saving for the future, the same dynamics can get him back off track. Inertia is at least working in our favor once we have made a good decision, but the cost of getting off track for just one day remains low, while the long-term costs of getting off track remain very high.

Of course, as mentioned before, these dynamics are not unique to saving. They underlie a wide range of life decisions where what we would prefer to do and what we know we ought to do are in tension. And these dynamics illustrate why we are often so bad at holding ourselves accountable: even when we know what to do, the decision to “start tomorrow” is often rational (at least for our short-term, hyperbolic discounting selves).

Human-to-Human Accountability is a Powerful Motivator of Behavior Change

Fortunately, there are many ways we can shift the dynamics of choices which are rational in the short-term and irrational in the long-term, in order to make ourselves more likely to enact and maintain positive behavior change. One powerful way is to use some of our social tendencies—namely our desire to avoid “failure” in the eyes of others—to hold ourselves more accountable when enacting change that we know would be good for us.

We can see this dynamic in play with many popular programs aimed at helping people make positive behavioral changes. For instance, Weight Watchers’ “Support Squad”, Financial Peace University’s “Accountability Partner”, and Alcoholics Anonymous’ (AA) “sponsors”. In each case, the social connection with someone else is intended to promote a greater level of accountability and success within the program.

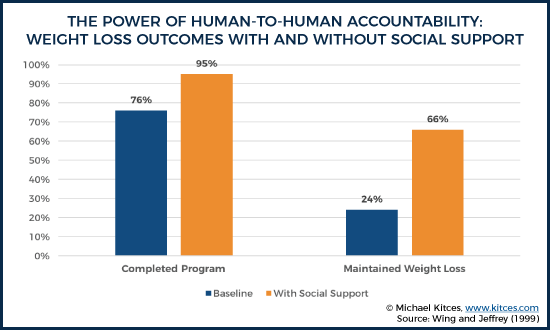

And there is some empirical evidence that a human-to-human connection (e.g., in the form of an “accountability partner”) helps improve behavioral outcomes. A study from Rena Wing of the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine and Robert Jeffrey of the University of Minnesota School of Public Health found that incorporating social support strategies improved weight loss outcomes over a standard behavioral treatment by itself. Specifically, the researchers found that among those who did not receive social support strategies with their weight loss program, only 76% completed the 4-month program and only 24% maintained their weight loss from months 4 through 10. By contrast, among those who received social support strategies, 95% completed the 4-month program and 66% maintained their weight loss from months 4 through 10.

Additionally, a 2012 study from Witbrodt, Kaskutas, Bond, and Delucchi evaluated sponsorship status and success in abstaining from alcohol consumption among AA members based on prospective 1-year, 3-year, 5-year, and 7-year follow-ups. The researchers found that sponsorship (where the individual in treatment has a “sponsor” to help them stay on track) improved outcomes even after controlling for attendance at AA meetings. When compared to alcoholics in the study with the lowest levels of sponsorship over time, those with the highest levels of sponsorship were 7 times more likely to remain sober.

The precise psychological mechanisms that lead us to be more accountable to others than we are to ourselves isn’t fully understood, though something to the effect of Charles Cooley’s “looking glass self” (whereby we evaluate ourselves based on how we believe others will perceive us) or perhaps Adam Smith’s “impartial spectator” (whereby we evaluate ourselves based on how a perfectly virtuous outsider would perceive us, while also aiming for social acceptance when it would be virtuous to do so) would both seem to be relevant. The bottom line, however, is that human beings are herd animals, and we truly do seem to be more accountable to others than we are to ourselves alone.

Thus, while it was rational (in the short-term) for John to delay saving in the example above, if John has met with his financial advisor and committed to a plan to start saving, then it may no longer be rational for John to put off saving in the short-term. While the financial cost of delaying each day is still small ($14), the social cost of failing to save has been increased. John knows that his financial advisor is aware of his goal to save, and has helped him put a plan in place. If John shows up to his next meeting with no progress to report, John’s assessment of himself through the eyes of his advisor is likely not positive. Instead of just encountering just a trivial financial cost for not saving, John encounters a financial cost paired with the social cost of seeing himself as a failure through the eyes of his advisor.

In this way, we can view the decision to share our goals with others and involve them in the process of accomplishing those goals (including the decision to hire a financial advisor) as a form of social “commitment device” (i.e., a self-imposed means of altering our short-term incentives in a way that makes us more likely to accomplish our long-term goals). In other words, acknowledging that we aren’t the best at holding ourselves accountable, we can involve other people in our goals to make ourselves feel a greater sense of obligation to accomplish them.

How Advisors Can Utilize Human-to-Human Accountability When Working with Clients

Fortunately for advisors, human-to-human accountability is beneficial in several ways. First, it represents a key value-add that advisors can provide which will be hard for computers to ever mimic. While technology can provide some useful commitment devices as well (e.g., software which can block distracting websites and help you be more productive), social commitments to other humans will be inherently more useful in some circumstances. For instance, a known limitation of much productivity enhancing software is that it requires the user to continually opt-in to using it. If a user is getting annoyed that their productivity software is blocking certain websites, they can simply turn the software off. While one may feel a little self-imposed guilt for doing so, the dynamics are different than when working with a human.

Additionally, sometimes the well-intentioned use of technology can actually make matters worse. A 2016 study on the use of wearable fitness technology in The Journal of the American Medical Association found that when compared to a standard weight loss intervention (low-calorie diet, increased physical activity, and group counseling sessions), participants in a technology-enhanced intervention group (same treatments as before, with the addition of a fitness tracker) actually lost less weight! Specifically, participants in the standard behavioral intervention group had lost an average of 13lbs at the end of a 24-month period, whereas the technology-enhanced group had only lost an average of 5.3lbs. While the reason for this difference is unknown, one possible explanation is that the technological confirmation of “good” behavior leads people to engage in some motivated reasoning aimed at rationalizing “bad” behavior. For instance, seeing that I exceeded my step goal for the day might make me less inclined to turn down dessert, with the net result that I eat more “bonus” calories than I lost from the technology-measured exercise in the first place!

But the key point is to acknowledge that social accountability is different than self-imposed or technological accountability. When a human is involved, we often have few options for totally avoiding the unfavorable perceptions we think others may have about us if we don’t follow through on our goals. In the extreme, we can do our best to disappear and never see someone again, but we still know that other person knows we dropped off the face of the earth and likely has some negative perceptions about why we may have done so (not to mention the social impropriety of such a disappearance). This creates a permanence associated with human-to-human accountability that can’t be easily replicated in other ways.

Notably, an advisor doesn’t actually have to have harsh judgments of their clients for human-to-human connection to be effective. Indeed, AA sponsors are encouraged to express kindness, respect, and empathy towards their sponsees – though the ability and willingness to deliver the “hard truth” is important as well. But the fact that the social connection is there means that clients may still wish to avoid “failure” in the eyes of others, even if they know those others will be compassionate and respectful towards them.

Using “Action Items” to Generate Clearly Articulated Expectations

One particular way advisors can encourage behavior change through human-to-human connection is by not only giving clients recommendations of what they “should” do, but helping clients develop explicit “action items” that they commit to completing. If advisors allow clients to leave action items in vague terms, the influence that social pressure can have on these goals is diminished. For instance, a vague goal to “start saving more” doesn’t define when or how much a client would need to shoot for in order to successfully fulfill their goal. By contrast, a goal to boost savings in one’s 401(k) to the annual maximum by the end of the month gives a client a clear goal which can actually be evaluated.

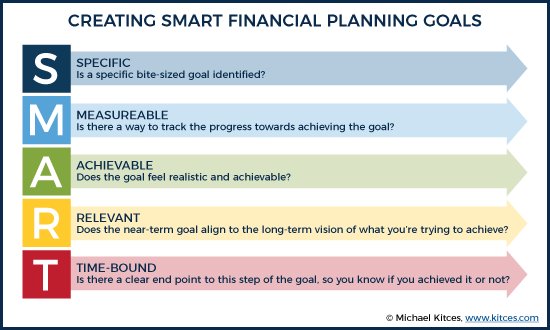

Goals and their supporting action items should ideally adhere to “SMART” criteria, meaning they are specific, measurable, achievable, results-focused, and time-bound. When these criteria are met, then a client who doesn’t incorporate the agreed upon changes will feel a sense of failure for not having done so. However, if the criteria are not clear or an advisor just provides an open-ended recommendation with no buy-in and commitment from the client, then the social pressure is greatly diminished. After all, the client can simply say to themselves, “Sure, my advisor recommended I start saving, and I’m saving 2% now, so I guess that’s good, right?” Or, “My advisor suggested I start saving 15% and I thought that was a good idea, but we never said when I should start. That’s probably something that’s best to start next year.”

Of course, advisors don’t need to play the role of a dictator when establishing these goals to clients (and there are good reasons to believe that approaches such as solution-focused financial therapy, which allow clients to develop their own goals and solutions will result in better outcomes), but the key point here is that the goals which are ultimately developed should be made explicit. If those goals are not made explicit, then clients have no way of truly evaluating whether they accomplished them or not, and the social pressure of not wanting to see oneself having failed through the eyes of their advisor is diminished.

Perhaps something akin to the following conversation could set clear action items, even if the client themselves generated the goal: “John, you mentioned that you should probably start boosting your savings in order to reach your retirement goal. I ran the projections and I agree. My projections show you should probably be saving closer to 15% compared to your current 10%. You felt that 15% was a reasonable savings amount, so would you be comfortable setting an action item that you’ll boost your savings to 15% by the end of the month?” This approach is not dictatorial, but it also ensures a SMART action item is generated so that the client feels some social pressure to actually follow through.

It is also important to note that it is assumed here that a goal aligns with what a client wants to accomplish, and therefore “failure” does not inherently imply any particular type of behavior. For a client who struggles to spend, “failure” may mean the client didn’t follow through on their goal to take their family on a trip or give more to a cause that is important to them, even though “failing to spend” would likely have a positive impact on their net worth.

Leveraging Social Forces Outside of The Advisor-Client Relationship

Another important source for enhancing client outcomes through human-to-human connection is to encourage relationships outside of the advisor-client relationship which can help clients engage in better behaviors.

While advisors tend to have mixed (and often very strong) feelings about programs such as Financial Peace University (FPU), arguably one of the most powerful aspects of such programs is the social reinforcement of the principles taught. Dave Ramsey lays down some hard rules for the group and once per week (or more) the group can help encourage each other, reinforce group norms, and hold each other accountable.

Advisors often object to some of the hard rules established in programs such as FPU (e.g., avoid all debt), but I suspect such criticism largely misses the point. People attending programs like FPU generally aren’t looking to explore the most sophisticated ways they can utilize debt to enhance their financial situation. Instead, they’ve often found themselves in a tough spot and realize they need to fundamentally change their behavior. Unlike a complex decision tree of all the various and nuanced ways in which debt can be prudently utilized, cutting up credit cards and only using cash generates the type of group norms which can be socially reinforced.

Since most advisors can’t realistically spend as much time with their clients as group based financial programs do, suggesting clients attend such programs is one way advisors can encourage their clients to develop some good financial practices. While there may only be a small number of such courses, other options include things like YNAB (You Need a Budget) and even blogs such as Mr. Money Mustache which facilitate “Meetups” for community members to get together. If a client truly trusts their advisor, then adding nuance to overly simplified rules once the client has achieved the behavior change they are looking for will likely not be a huge barrier to overcome.

Similarly, advisors can encourage clients to evaluate the ways in which various social groups they belong to are currently influencing their spending – regardless of whether it is positive or negative. For instance, an individual may want to reconsider how they engage with a social group which puts them in situations where they continually feel the need to stretch their budget, just as it’s hard to quit smoking if you still spend time with smokers, or to quit drinking if you spend time with friends who regularly drink. Additionally, they may want to look for other social groups they can join which will provide positive reinforcement for behaviors an individual is trying to develop.

Ultimately, human-to-human connection plays an important role in how develop and foster good financial behaviors. Fortunately for advisors, this not only means there will likely always be a role which cannot be fulfilled by technology (further suggesting the cyborg advisor has far more potential than the robo advisor), but also that human-to-human connection can help clients achieve better financial outcomes. Advisors may be able to help clients improve outcomes by setting clearly defined goals that encourage clients to feel as though they have some objective criteria to be evaluated by, and also by encouraging clients to consider the ways in which social connections in other areas of their life can help encourage or discourage prudent financial behaviors.

So what do you think? Can the social influence of human-to-human connection help clients make better financial decisions? Are we more accountable to others than we are to ourselves? Do you use action items to help hold clients accountable? Please share your thoughts in the comments below!