Executive Summary

The conventional view of portfolio rebalancing is that it is a strategy to enhance long-term returns by periodically selling the investments that are up (and overweighted) to buy those that are down (and underweighted), in the process of realigning the portfolio to its original target allocation.

Yet the reality is that because most investments go up far more often than they go down, systematic rebalancing is actually more likely to just consistently liquidate the best-performing investments to buy ones with lower returns instead – especially when rebalancing across investments that have very significant return differences in the first place (e.g., rebalancing from stocks into bonds).

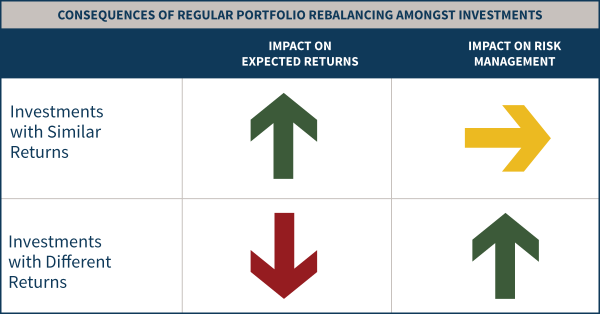

As a result, rebalancing may be helpful as a risk management strategy – otherwise higher-returning stocks would compound to the point that they are significantly overweighted relative to lower-returning bonds – but it’s only when rebalancing amongst investments with similar returns in the first place that rebalancing provides a return-enhancement potential.

Ultimately, the fact that rebalancing may actually reduce long-term returns isn’t a reason to avoid it (even if returns are lower, risk-adjusted returns may be improved if the risk is reduced by even more), and sometimes returns really can be enhanced (when rebalancing across similar-return investments, such as amongst sub-categories of equities). Nonetheless, it’s crucial to recognize the role that rebalancing really does – and does not – play in a long-term portfolio!

How Portfolio Rebalancing Can Actually Reduce Long-Term Returns

The basic concept of portfolio rebalancing, as the name implies, is to realign the balance of investments in a portfolio, generally to stay in accordance with the original target weightings for that portfolio. And in a world where asset classes can have materially different long-term returns, this is crucial to ensure the portfolio does not compound to the point of violating the investor’s risk tolerance.

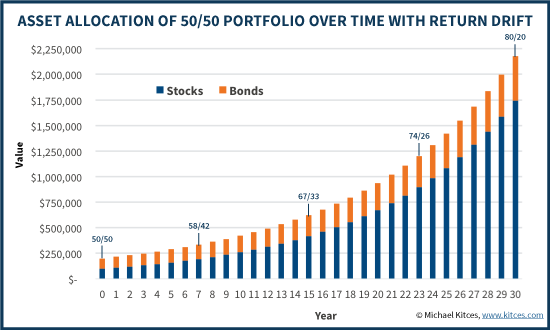

For instance, consider for a moment the fact that the long-term return on stocks is about 10%/year, while the long-term return on bonds is only 5%. A portfolio that is allocated 50/50 to each, and buys and holds those asset classes for the long run, will grow the stock portion at 10%/year compounding, while the bond portfolio will “only” grow at 5%/year. Which means that with growth, the percentage of the portfolio allocated to equities will become larger and larger over time.

As shown above, the “bad” news of this scenario is that over time, the excess returns of the stocks over the bonds will cause the stocks to become a larger and larger portion of the portfolio. What starts out as a 50/50 portfolio drifts to 67/33 by 15 years, and nearly 80/20 after 30 years! Thus, just buying and holding a stock/bond portfolio will eventually lead equity exposure to become far greater than what was originally intended, and perhaps greater than what the client can tolerate.

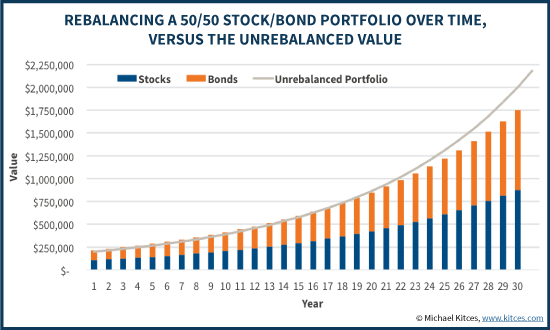

Yet the reality is that to keep the client’s equity exposure from drifting too high, cumulative portfolio returns will actually be reduced by systematic rebalancing, not enhanced! After all, rebalancing in this scenario will just end out systematically selling the higher-returning asset (stocks) to buy more of the lower-returning asset (bonds), which just drags down the long-term return!

As shown above, the process of rebalancing to prevent equity exposure from drifting higher also curtails the favorable returns that come with allowing equities to compound! The portfolio that starts out at $100,000 each in stocks and bonds and is annually rebalanced only grows to $1,750,991 over time, compared to the buy-and-hold-and-don’t-rebalance portfolio that grew to $2,177,134 instead!

Granted, the latter portfolio only grew to greater wealth because it allowed equity exposure to drift higher and higher, potentially beyond the client’s tolerance (and the client may not have even needed to take the risk!). Yet still, the process of rebalancing the portfolio to keep that risk exposure constant was not a return enhancement; instead, it was a detriment to returns, but a trade-off that may have been deemed necessary to manage risk.

The Risk Management Benefit Of Portfolio Rebalancing With (Real-World) Volatility

Of course, a notable caveat of the prior examples about the impact of rebalancing between stocks and bonds is that while stocks may outperform bonds in the long run, they rarely ever do so in the exact “straight line” path shown above. Instead, bond and especially stock returns are more volatile, introducing the possibility of selling stocks when they’re up to buy bonds when they’re down, or selling bonds when they’re up to buy stocks after a crash.

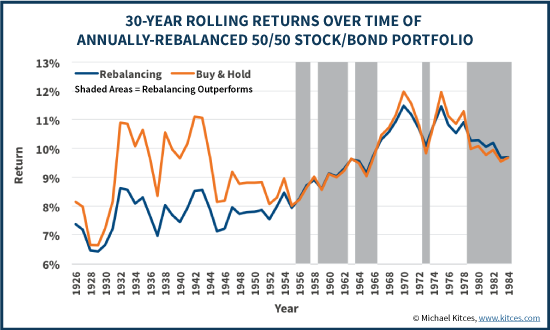

The question emerges, then, of whether there’s more return given up in the long run by rebalancing out of higher-return stocks into lower-return bonds, than is gained by the timing of those rebalancing trades to capture the sell-high-buy-low opportunities given volatility along the way.

The chart above shows the outcome of this process over rolling 30-year historical periods, for rebalancing between large-cap US stocks and intermediate-term government bonds. As the chart reveals, in the long run, most portfolios are still consistently giving up returns by rebalancing from stocks into bonds in the long run. And in scenarios where the rebalanced portfolio does beat the buy-and-hold portfolio (the blue line is above the orange line), the difference is generally negligible.

Of course, given that an unrebalanced portfolio can drift to 80%+ in equities over a multi-decade period, regular rebalancing in such situations may still be appealing as a means to manage risk and avoid excess exposure to (the excessive compounding of) risky-but-high-return investments. Still, what this ultimately means is that in situations where rebalancing is occurring between stocks and bonds, the reality is that rebalancing is not a return enhancing strategy, but instead a return reducing strategy that is done for risk management purposes. (Though, notably, the results may lead to slightly higher risk-adjusted returns, and a slightly improved Sharpe ratio.)

Enhancing Returns By Rebalancing Amongst Equities (Or Other Similar-Return Asset Classes)

While rebalancing between high- and low-return asset classes (e.g., stocks and bonds) becomes a process that systematically sells higher-returning investments to buy those with lower returns (and therefore enhances risk management but generally reduces returns), in the case of rebalancing between investments that have similar returns, the outcome is different.

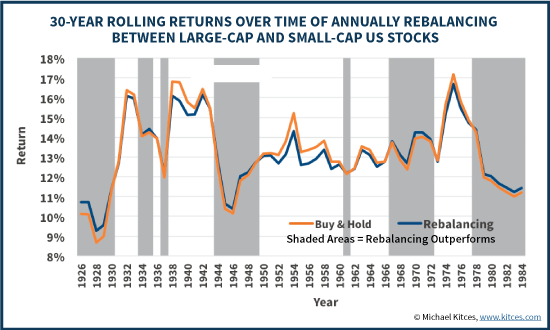

The distinction is that when the available investment choices have a roughly similar long-term return, rebalancing amongst them will not necessarily reduce the long-term compounding of high-return investments. Instead, it will simply create opportunities to sell-high-and-buy-low as the investments periodically outperform or underperform each other (even as they converge on similar long-term returns).

In other words, if we assume that the investments will have a similar long-term return, then short-term outperformance by one implies that the other may be more likely to outperform in the future as their long-term returns revert towards the (equal) mean of the two. Which in turn means that rebalancing amongst them actually should be able to take advantage of those regression-to-the-mean opportunities.

And in fact, that’s exactly what we see when we look at two volatile asset classes – large cap and small cap US stocks – which do have roughly the same long-term expected return (small cap stocks have historically outperformed, but only slightly). Rebalancing between the two, which have similar returns and a high-but-not-perfect (i.e., less than 1.0) correlation, actually does enhance the returns compared to just buying-and-holding each, as shown below.

In fact, investment guru William Bernstein (in a white paper aptly entitled “The Rebalancing Bonus”) found that in general, for similar-returning asset classes, the higher the volatility of assets and the lower their correlations – creating even more rebalancing opportunities – the greater the potential “Rebalancing Bonus” will be. (Though Bernstein also noted that with different-return asset classes, like rebalancing across stocks and bonds, the rebalancing process will lead to lower returns, albeit with the ‘benefit’ of lower risk.)

The Fuzzy Economic Benefits Of Portfolio Rebalancing – Better Returns, Just Risk Management, Or Enhancing Risk-Adjusted Returns?

When it comes to quantifying the economic benefits of rebalancing, estimating the value is ‘surprisingly’ difficult, due in large part to the previously discussed distinction that rebalancing amongst similar-return investments may be a return enhancement but with different-returning investments it is often not.

For instance, a 2010 study from Vanguard by Jaconetti, Kinniry, and Zilbering found that rebalancing stock/bond portfolios reduced returns, generally by about 0.50% in the long run. Portfolio volatility was reduced as well, but simply because rebalancing reduced the average equity exposure (which otherwise compounded to 80%+ equity portfolios over multi-decade time horizons!). Though the significant reduction in volatility, combined with only a ‘slight’ reduction in returns, did enhance risk-adjusted returns.

Other studies have found a return enhancement to rebalancing, but typically no more than 0.50%/year (and often less), with the results highly contingent on the breadth and nature of the underlying asset classes used in the analysis. Ironically, the more equity-centric the portfolio already is – and the more sub-categories of equities that are used – the better rebalancing looks, as it limits the return-reducing aspect of systematically selling high-return investments (e.g., stocks) to buy lower-returning ones (e.g., bonds).

In other words, in the context of Bernstein’s “Rebalancing Bonus” study, the benefits of rebalancing will vary directly as a function of types of investments/asset classes held, and in particular the differences in the volatility of the investments, along with how low their correlations are with each other. In this context, the best investments for rebalancing are the ones that are volatile, can deviate significantly from each other, and tend not to move in sync (creating more opportunities for those deviations where rebalancing trades can occur). Yet if rebalancing occurs only between those and not between lower-return investments (e.g., bonds) as well, eventually the portfolio may spin up to an untenable level of overall risk.

The bottom line, though, is that either way rebalancing produces some benefit, whether it’s risk management (across high- and low-return investments that are compounding), higher returns (across similar-returning investments with less-than-perfect correlation), or better risk-adjusted returns (where returns are reduced but volatility is reduced even more). But it’s important to recognize in which situations each may apply, as it can impact both the way that rebalancing is best implemented, and the expectations to set about its prospective benefits for doing so!

So what do you think? Do you engage in regular rebalancing for client portfolios? Over what frequency? Do you explain it as a return-enhancing strategy, or primarily for risk management? Please share your thoughts in the comments below!