Executive Summary

As the pace of advisory firm acquisitions slowly but steadily increases, more and more attention is being paid to the "going rate" valuations of advisory firms, with some recent mega-deals valued at upwards of 2.0X recurring AUM fee revenue.

Yet the caveat is that not all advisory firm acquisitions are treated the same for tax purposes. Earn-out arrangements result in the purchase price being taxed as ordinary income to the seller, while others deals that purchase the underlying business assets may be treated as a capital transaction eligible for long-term capital gains treatment. As a result, a deal that is reported at 2X revenue could actually be worth another 15% more (or quite a bit less) depending on the tax treatment.

The issue is further complicated by the fact that the treatment most favorable to the seller - taxation at long-term capital gains rates - is least favorable to the buyer, who will be compelled to spread the cost of the purchase for tax purposes over 15 years as "goodwill amortization" even though the cash flows for the purchase occur immediately. As a result, the tax treatment of the deal can be a significant factor in setting the price itself, as buyers may pay more for a deal with more favorable tax treatment for themselves, and sellers may accept less if they can receive more favorable tax treatment on their end.

In this guest post, advisor Daniel Zajac shares his perspective on how the valuation of an advisory firm can swing by 15% or more, based on both the tax treatment to buyers and sellers and the expected growth rate of the practice. Whether you're considering the sale of your own practice, or are a prospective buyer of one (either as a way to start out as a financial advisor, or to make your existing advisory firm bigger), hopefully this information will help you gain a better understanding of the tax issues to consider that may influence the valuation of the firm involved!

If you follow the financial services industry, then you know that succession planning is a popular topic. With an aging advisor demographic and a limited pool of qualified and able advisors that are able to buy, the market finds itself in a unique position. Owners of advisory firms, by choice or by circumstance, are finding it difficult to effectively coordinate and implement a succession plan.

Even so, succession planning remains a hot topic. When discussing succession planning, many things should be considered. However, one topic continues to bubble up to the top of conversation. That topic is valuation: How much is a practice worth?

One common solution used to assess the fair value of a firm is the multiple of revenue. But what factor, multiplied by your recurring revenue, is accurate to valuate a firm. A frequently referenced rule of thumb has pegged the value of a financial services firm at about 2.0 times its recurring revenue.

What do I think of this overly-simplified metric, as someone who actually looks to buy advisory firms? It’s too simple, too easy, and too general!

If you’ve read my previous article on a buyer’s take on succession planning, you will know that for me, the multiple of revenue (or valuation) is secondary to many other issues. When evaluating a potential partner to purchase, the firm philosophy, firm make-up, owner/employee personalities, target and niche markets, and areas of specialization are critical factors. For me, these aspects influence my decision in evaluating a firm far more than a multiple of revenue.

But beyond even these factors, it turns out that one of the most significant drivers for the valuation of an advisory firm purchase is simply based on how it’s structured for tax purposes. For instance, I can compute that a deal valuing a business at a 2.0-times multiple of recurring revenue equals an identical business valued at a 2.3-times multiple of recurring revenue (based on the net present value [NPV] of the transaction). That’s a 15% swing in the valuation of the business, just depending on how those cash flows are treated for tax purposes to the seller!

An Example Of A Prospective Advisory Firm Acquisition

Let’s assume that we have the following practice for sale.

- Total Recurring Revenue - $500,000

- Total Non-Recurring Revenue - $0

- Total Expenses - $75,000 (100% of expenses will be assumed by the buyer)

Let’s also assume the following deal terms, which will remain constant for our example (unless otherwise specified).

- Down Payment - 33%

- Earn-out - 67% over 5 years

- Retained Business - 100%

- Growth Rate - 0%

With our assumptions in place, we can calculate the after-tax cash flows to the seller and the cash flow obligations and NPV as calculated by the buyer.

Scenario 1 – Valuation At 2.0 Times Recurring Revenue, Treated as an Earn-Out

If we assume that the above practice will be sold at 2.0x its recurring revenue, here is what we know:

- Purchase Price – $1,000,000

- Down Payment - $330,000

- Earn-out for next 5 years - $134,000

As a seller, it’s important to know that these numbers only tell part of the story. As we know, as financial advisors, it’s not the purchase price that matters. The number that truly matters is the total after-tax cash flows received by the seller.

With the terms of the agreement stating that cash flows beyond the downpayment are an earn out, only the downpayment will receive capital gains treatment; the remaining earn-out is received as earned income by the seller, taxed as ordinary income. In turn, the buyer will be able to deduct all of the earn-out payments paid to the seller in the year that the expense is incurred (and the downpayment is typically amortized by the buyer as goodwill over 15 years, assuming there were negligible other business assets).

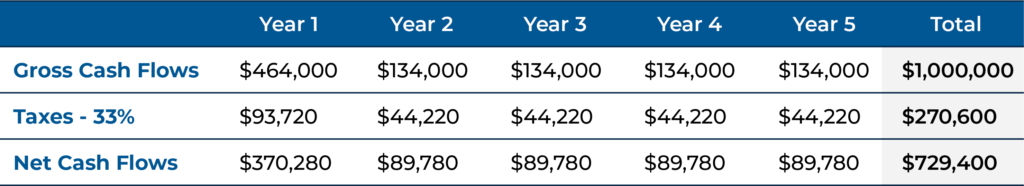

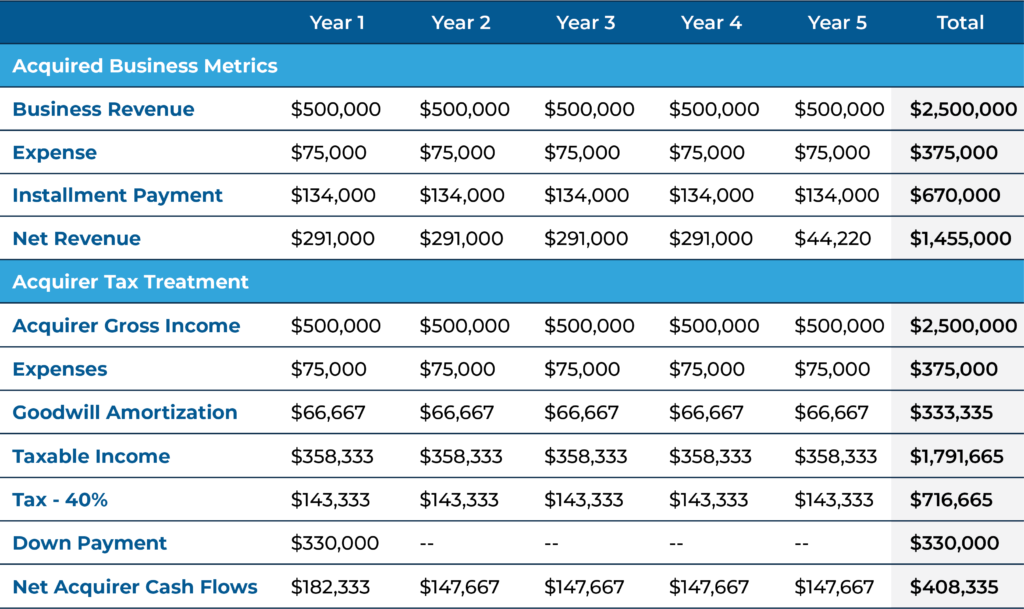

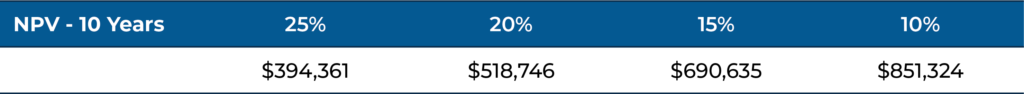

Entering these figures into a tax return, we can calculate the total after-tax cash flows received by the seller and the buyer. As shown in the chart below, the total amount the seller would receive is $729,400, assuming a 33% marginal tax rate on ordinary income and 15% capital gains on the downpayment portion.

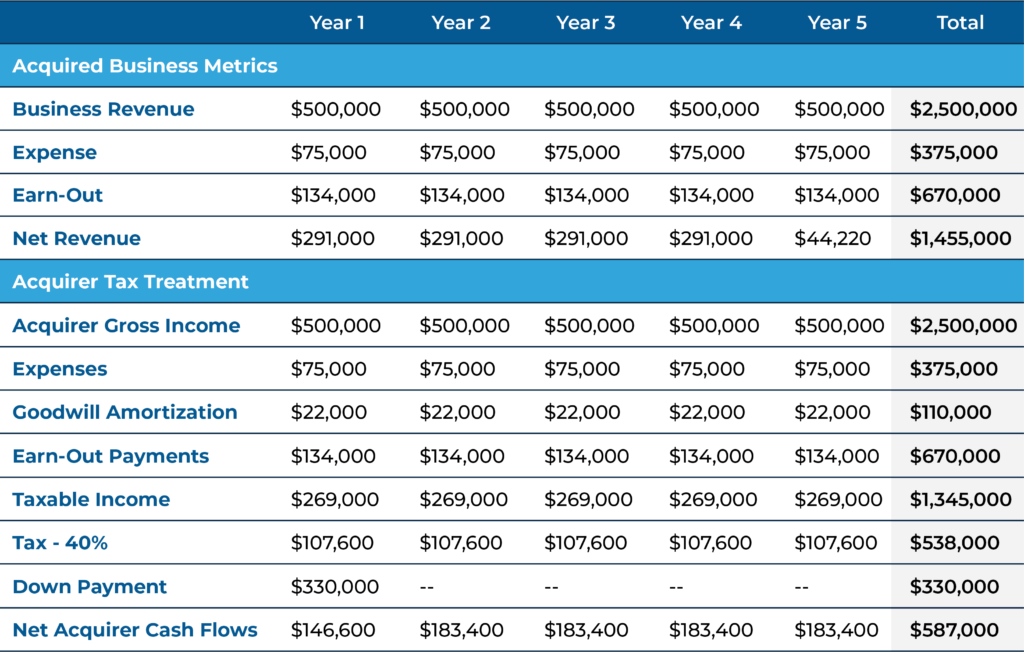

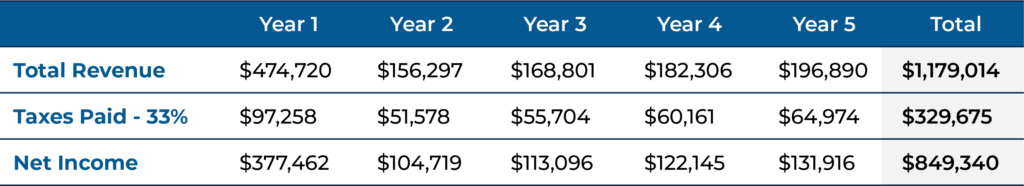

Buyer cash flow is detailed below, assuming a 40% marginal tax rate:

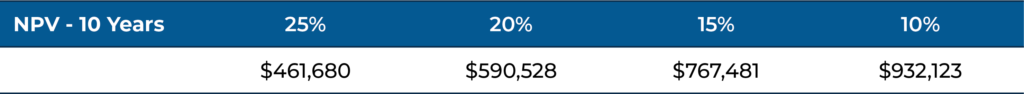

In addition, I calculated the 10-year net present value of the above transaction for the buyer using various discount rates. You’ll notice that this deal can range from approximately $461,680 to $923,132 based on the various discount rates sampled.

All else being equal, treating a deal as earned income works in favor of the buyer, who gets to fully deduct all the purchase payments (though as we discuss later, one key benefit for the seller is the ability to participate in subsequent upside).

Scenario 2 - Buying A Firm For 2X Revenue When Treated As An Asset Purchase Capital Transaction (With Goodwill Amortization)

Now that we have the foundation for comparison, let’s evaluate the same deal mentioned above with one change. We will treat the deal as an entirely capital transaction by buying the assets from the seller (or the seller's entity), not earned income by paying an earn-out to the seller. When the deal is treated as a capital transaction, the tax structure of the deal is substantially different for both the buyer and the seller.

For the seller, the sale of tangible assets may be subject to ordinary income or capital gains treatment, but the overwhelming bulk of the purchase price will generally be treated as a capital transaction for typically-zero-basis goodwill and be eligible for capital gains tax treatment at favorable tax rates (as compared to being treated as ordinary income for the seller with an earn-out).

For the buyer, the bulk of the purchase price (again treated as "goodwill") is able to be amortized over 15 years as a “goodwill” intangible asset. This means that instead of the buyer deducting the full amount of the earn-out payments made to the seller (in this example, $134,000), the buyer each year will only deduct $1,000,000 divided by 15, or $66,667 for each of the next 15 years (if 100% of the purchase price was goodwill, although in practice it will usually be something slightly less than 100%, as there are usually at least some other business assets for a small portion of the purchase price).

Looking at the buyer’s cash flow, we calculate that $134,000 needs to be paid out as an installment note expense for the purchase amount (above and beyond the downpayment), but only $66,667 of that payment can be deducted (amortizing the goodwill, assuming it is 100% in this example). Thus, the acquired practice is generating profits being used to finance the purchase payments, but the buyer can’t deduct all of the purchase payments as they go out the door!

Notably, during the period of payments to the seller, this has a negative effect on cash flow, as the buyer pays tax on money that is not retained. However, during the following years once the seller has been fully paid, until the final year of the scheduled amortization (in this example, Years 6 through 15), this has a positive effect on cash flow, as the buyer continues to receive a deduction, while no money is being paid out as due to the seller.

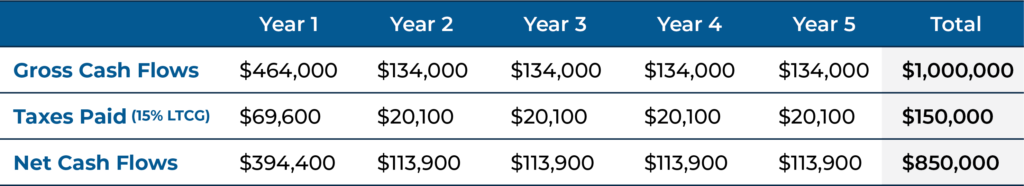

If we enter these figures into a tax return, we can calculate the total after-tax income that may be received by the seller. You can see that by treating this deal as a capital transaction, the total amount received by the seller would be $850,000 (assuming a 15% long-term capital gains rate). This is significantly more than the $729,400 the seller finished with when the same purchase price was paid as an earn-out at ordinary income rates!

After-Tax Cash Flows to the Seller:

As a buyer, we can calculate the following potential after-tax cash flows (again at the same 40% ordinary income marginal tax rate):

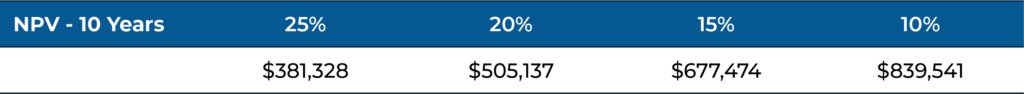

If we evaluate this deal in terms of net present value, we see that the value of the business goes down for the buyer, despite the same purchase price, because of the less favorable tax treatment (amortizing payments over 15 years, instead of deducting them as paid). In this example, the value ranges from $381,328 to $839,541, a decrease of more than 20% for the buyer, as compared to the deal in Scenario 1.

Scenario 3 – Equalizing The Valuation Of An Advisory Firm Based On Tax Treatment To Buyer And Seller?

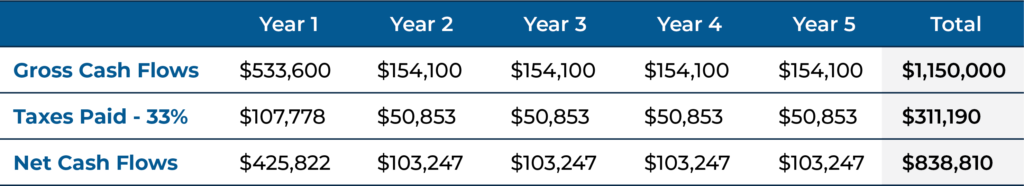

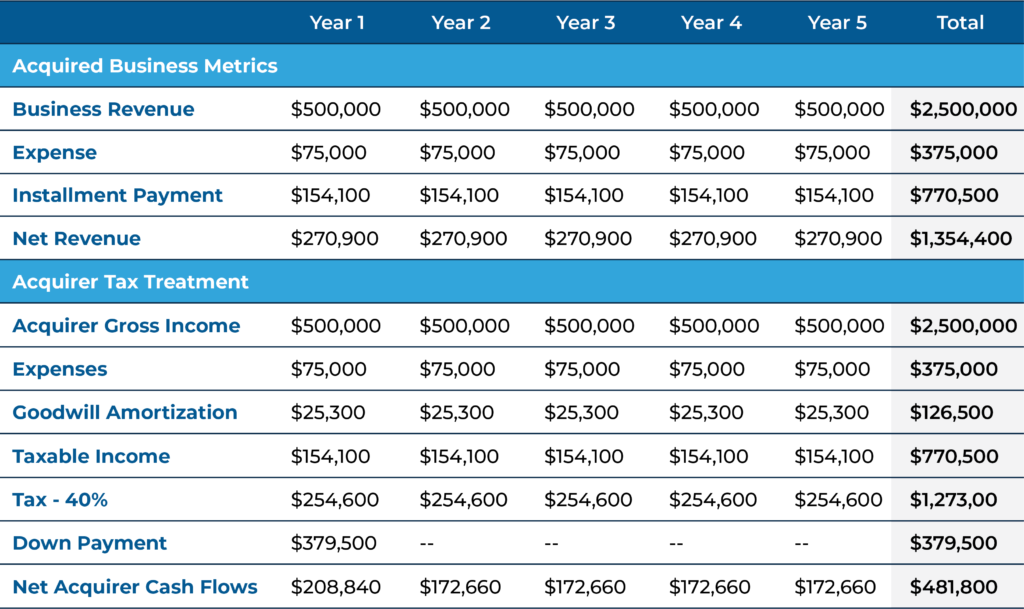

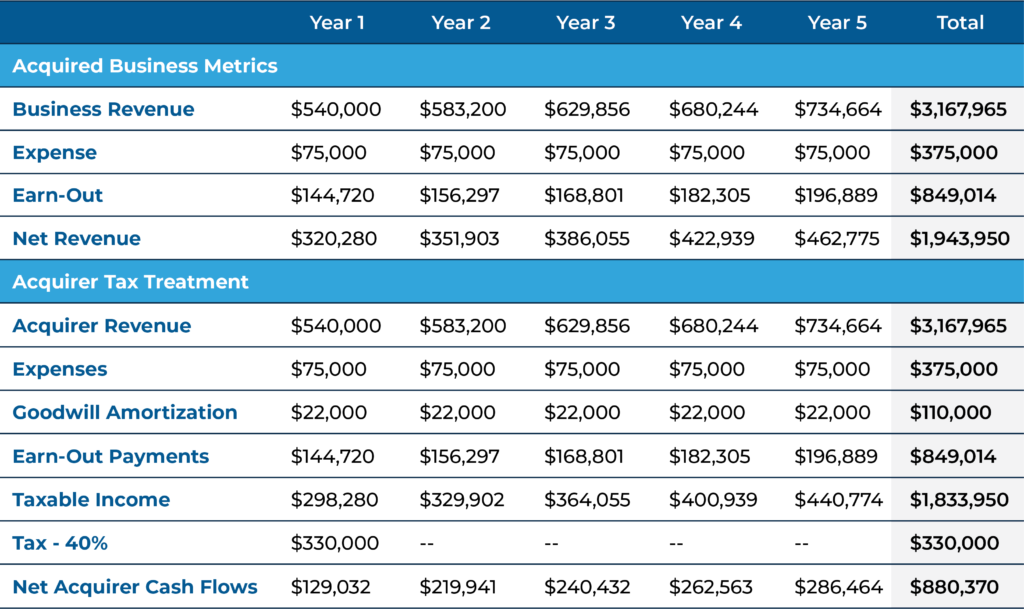

This discrepancy in value leads to an important question: at what factor of recurring revenue does a deal treated as a capital transaction equal that of a deal treated as ordinary income? The answer (in this deal structure) is 2.0x and 2.3x. A 2.0x deal taxed as a capital transaction equals a 2.3x deal taxed as ordinary income. Stated another way, a deal that values the same practice at $1,000,000 is approximately mathematically equivalent to a deal that values the business at $1,150,000 with an alternative tax structure. Or viewed another way, a seller who is willing to accept ordinary income treatment may find the buyer is willing to offer a purchase price that is nearly 15% higher (as it’s still the same net present value for the buyer thanks to the more favorable tax treatment for the buyer)! Let’s look at the numbers, assuming the same practice but with a buyer willing to offer a $1.15MM deal that is structured as ordinary income earn-out. You will observe that as the purchase price is adjusted, the down payment and the ongoing earn-out payments must be adjusted accordingly. In this example, the down payment was increased from $330,000 to $379,500 and the earn-out went from $134,000 to $154,100, given the $1,150,000 instead of $1,000,000 purchase price. Seems like a no-brainer for the seller! Not so fast! The more favorable tax treatment that made the deal appealing for the buyer is less favorable tax treatment for the seller, who gets a higher purchase price but keeps less of it! In fact, the after-tax income received and the net present value calculations could leave both the buyer and the seller in a substantially equal place! In this deal, the seller would receive $838,810 of after-tax cash flows (as compared to $850,000 in the earlier example).

The buyer cash flow is as follows:

The buyer would have a net present value that ranges from $394,861 to $851,324 (as compared to $381,328 and $839,541).

In other words, ultimately the final after-tax cash flows of the deal are remarkably similar for both the buyer and the seller, despite the fact that the headline purchase price was 15% higher, because of the offsetting change in tax treatment!

How Does Growth Affect The Valuation Multiple Of An Advisory Firm?

If you find a buyer who is looking to strategically acquire another firm, it’s reasonable to assume that the buyer has a short- and long-term growth vision for their firm. It’s unlikely that buyer will be inclined to purchase a firm that will restrain this desired growth trajectory. Therefore, assuming the buyer and the seller are compatible about growth goals of the combined firm, the buyer and the seller may be mutually interested in structuring a deal where both parties participate in the potential growth (and take the risk of potential loss) of the combined entity. This relies on structuring the deal as an earn-out, with the associated income tax consequences for the buyer and the seller. This sharing of potential growth and loss of the combined firm could have many potential positive implications. Should the transition go well, both would experience an increase in income. Should the transition fail, both parties would experience a loss of revenue. Which means both parties are financially incentivized to remain actively engaged in transitioning clients successfully to the new firm and ensuring it subsequently grows. Thus, assuming the parties in the transaction agree that growth is an important consideration for the combined entity, both parties may want growth to be included as part of the deal structure (as an earn-out) and setting a purchase price. Including growth in the deal structure provides us with another interesting break-even point to calculate. That break-even point is: at what growth rate is a 2.0x earn-out transaction equal to a 2.0x buyout that is treated as a capital transaction (assuming no growth). The answer – 8%.If the seller believes that the buyer can purchase the business and grow at 8% or more during the 5-year buyout period, the seller (even taxed at the less favorable ordinary income rates) would earn more from the total buyout by structuring the deal as an earn-out to participate in the growth. Again, we refer to a cash flow analysis (below). In doing so, we can calculate that the seller would receive $849,339 in after-tax income from this transaction, based on a practice growing at 8%/year but being taxed as ordinary income. This compares to $850,000 received by the seller, assuming a 2.0x deal with zero growth that is taxed as a capital transaction.

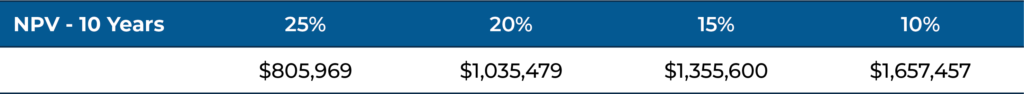

As a buyer, here is a look at cash flow assuming a 40% tax bracket:

And finally, a look at the net present value calculations:

Interestingly, the seller would receive nearly the same amount of after-tax income as compared to the 2.0x deal that is structured as a capital transaction. However, the value of the two deals using NPV discounted back at 25% is far from equal for the buyer. In fact, the NPV calculation on this deal structure, assuming a 25% discount rate, values the deal at $805,969. Referring back to the 2.0x deal as a capital transaction, the same 25% discount rate values the deal at $381,328 - over 50% less. Future growth is extremely valuable for buyers!

Takeaways On Tax Treatment And Advisory Firm Valuations

The calculations above attempt to explore how various deal structures can heavily influence the valuation of a firm, while potentially producing the same after-tax income to the seller. It’s an attempt to evolve the discussion of succession planning away from an overly simplified rule of thumb. In short, the analysis above shows that just using a simple valuation multiple like 2X recurring revenue could be inadequate when evaluating a financial services firm. The multiple of revenue is only one piece of a very complicated puzzle. The examples above reveal that the tax treatment of a transaction alone can swing the “value” of the business by 15% (or more if there’s an even bigger differential in the tax rates of the buyer and seller!). And incorporating growth into the purchase price could impact fair valuation even further. If we continue the discussion of deal terms, we can assume that other factors may influence the overall deal structure as well. How much is the down payment? How much of the payout is guaranteed and how much is tied to the success of the combined business? How much expense can be saved through office efficiencies? Furthermore, is an employment contract part of the deal? As I suggested earlier in this article, a good succession plan is one that brings together like-minded firms with similar business and philosophical needs. A good succession plan is one that ideally leads to increased productivity, expansion into a new market, a merger into a larger and more capable firm, and a mutually committed vision to growth. A succession plan, when completed to its highest potential, is one where the seller is sufficiently compensated for their efforts, and the buyer is able to assume a reasonable amount of risk and reward potential. More than anything, this analysis suggests that focusing on the multiple of revenue as the primary driver for a deal could be misguided. The multiple of revenue, in the context of the terms of a deal, is only a small factor to consider, and one that may not be genuinely indicative of what’s “behind the curtain” of the deal.

So what do you think? Have you considered the tax treatment in an advisory firm acquisition as a buyer or seller? If you were going to purchase, would you pay less in order to get the more favorable tax treatment? As the seller, how much growth would you be willing to count on?

Daniel Zajac Compliance Disclosures: None of the information in this document should be considered tax or legal advice. You should consult your legal or tax advisor for information concerning your individual situation. Tax services are not offered through, or supervised by Lincoln Investment, or Capital Analysts. The above examples are hypothetical in nature. These do not represent any specific deal and should not be used as the foundation for any deal structure. Please consult your own advisor when evaluating your personal plan. Advisory services offered through Lincoln Investment or Capital Analysts, Registered Investment Advisors. Securities offered through Lincoln Investment, Broker Dealer, Member FINRA/SIPC.

SimoneZajac Wealth Management Group, LLC and the above firms are independent, non-affiliated entities.

So let me get this straight.

You’re going to use a 5 years of deductions of a 15 year amortization to compare against 5 years of full expensing? So apparently those 10 extra years of deductions when your net income is even higher (i.e deduction worth more) aren’t worth anything to you?

The best mutual tax treatment in the deal is capital gains. 15%(or 20%) to seller and ordinary income deduction to buyer (but over a longer period of time) which is a tax arbitrage.

More ordinary income only leads to a wash of ordinary income deductions with ordinary income earned with bracket differences as only arbitrage or lack of.

What stinks about capital gains treatment is phantom income which can make cash flow tight at the beginning, but you make up for it with effectively phantom deductions for the remainder of the amortization.

Also you can structure a purchase with a note classifying only a portion of future income as ordinary income via interest expense if you want.

I would do a near full cap gains deal at 2.1 vs 2 ordinary income easily.

As long as the person was willin to structure the deal over an appropriate time horizon where a serious cash flow crunch due to phantom income wasn’t a problem