Executive Summary

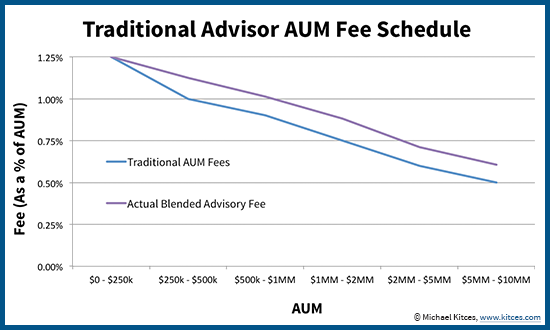

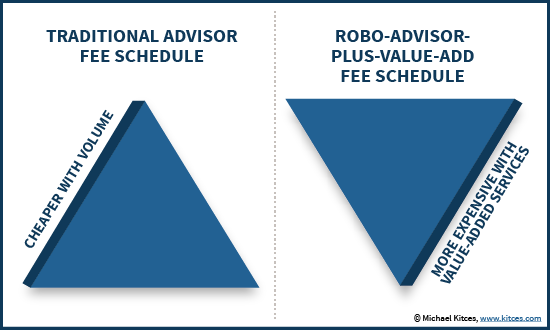

The “traditional” AUM fee schedule for an advisory firm has graduated breakpoint as asset levels rise, a tacit acknowledgement that it doesn’t really take twice the work to service a client with twice the assets, and that investment management (and/or with broader financial planning and wealth management services) is fundamentally an expensive service that gets cheaper with “volume” discounts as clients invest more.

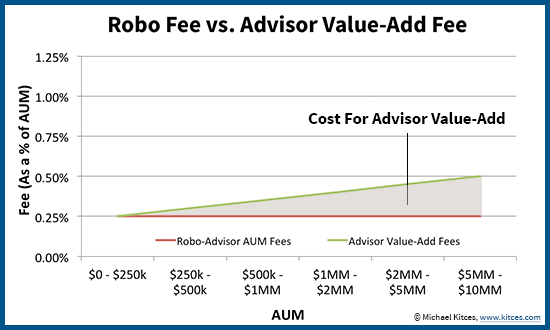

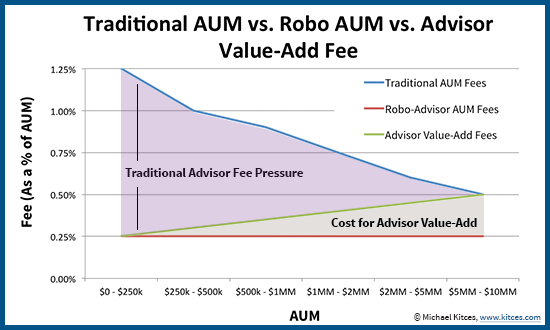

By contrast, today’s “robo-advisor” platforms simply charge a flat low AUM fee. While robo-advisors provide only a limited scope of services for that price point – not directly competing against a comprehensive advisor – the nature of charging a low price for a commoditized service implies that advisors can only charge more by explicitly offering additional value-add services (e.g., financial planning and wealth management) for an additional fee, that rises with the client complexity and depth of client service.

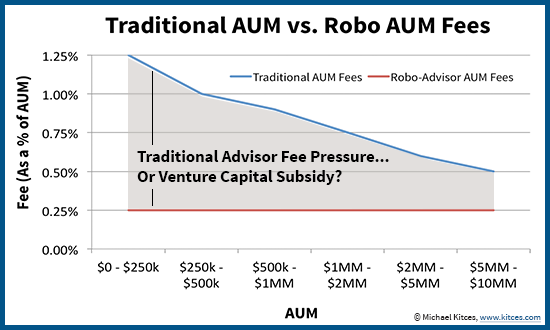

While the reality is that none of today’s “robo-advisor” platforms are actually profitable, and their business model is heavily subsidized by venture capital while they try to achieve scale, the difference in fee structures highlights a fundamental difference that will likely remain relevant for years to come: is investment management and supporting financial planning and wealth management services an “expensive” service that gets (relatively) cheaper to provide at larger asset levels, or actually a “cheap” service where higher net worth client can buy value-added services for an additional cost?

The Traditional AUM Fee Schedule And Volume Discounts

While mutual funds and ETFs by virtue of their structure have a flat and constant expense ratio, the AUM fee percentage for most advisory firms tends to get lower and lower as the AUM of the client increases. Thus, while the average AUM fee for a balanced fund was 0.80% in 2013, an advisory firm’s (hypothetical) fee schedule might look something more like the following:

The decreasing AUM percentages for advisory firms represent the tacit acknowledgement that while planning complexity does increase with net worth, it normally doesn’t really take twice the work to service a client with twice the assets, even if the firm overall is responsible for managing (and potentially liable for mismanaging) twice the assets. In other words, buying wealth management is implicitly cheaper when it’s bought “in bulk” with a larger chunk of assets.

Alternatively, one might also simply say that the higher price point at the lower end of the AUM scale is necessary for the advisory firm to be able to grow and scale in the first place. After all, there is a certain amount of infrastructure necessary to run and operate a firm, and to a large extent the capacity of an advisor is dictated more by the sheer number of clients to manage than their assets; thus, if the firm is going to service a larger number of smaller clients, it’s necessary to charge more simply to cover the overhead of the firm. And for most advisory firms, the reality is that the true blocking point to serving “small” clients at a lower price point is not actually due to the cost of delivering service to them, but the sheer (marketing) difficulty in acquiring them as clients in the first place!

Nonetheless, whether you ultimately want to view it as “smaller clients pay more to cover overhead costs of the firm” or “larger clients pay (relatively) less because they’re not that much more complex to service and are getting a volume discount”, the essence of the advisory firm pricing model is to start with a relatively high price point, and offer clients a gradually declining-percentage AUM fee as their AUM itself increases.

The New Lower AUM Fee Schedule With Value-Adds?

Contrasting the “traditional” fee schedule of advisory firms, is the fee schedule of today’s crop of “robo-advisors”, charging a flat – and very low – AUM fee for the core service of automating the implementation and monitoring of asset allocation. Of course, a robo-advisor solution is not directly comparable to a traditional advisory firm; the former may provide just a handful of portfolio-based value-adds like rebalancing and tax-loss harvesting, while the latter may be providing an ongoing relationship with an advisor providing comprehensive personal financial planning services.

Nonetheless, the presence of a core “robo” solution commoditizing the basic asset allocation service of a portfolio creates new pressure on traditional advisory firms to explain what it is that they do, on top of just asset allocating a portfolio, to justify incremental additional fees. In other words, the “robo” solution sets the floor, and the human advisor’s value (and cost) stacks on top, as the client complexity rises and justifies the additional value and cost a human advisor can bring.

From the perspective of technology driving the commoditization of basic investment management, the idea that investment services are actually a “cheap” basic service to deliver, with higher fees attached for (meaningful) value-added wealth management services, is the direct opposite of the traditional advisory firm, where investment management is an “expensive” service that gets incrementally cheaper to deliver with more assets (and wealth management is layered on top as a client attraction and retention strategy). Ironically, at very high-net-worth levels with deep wealth management value-adds, the cost of services may converge; the “pain” of fee pressure and commoditization is felt primarily at lower asset levels in particular, where the firm may not be offering much at all in the way of “value-add” services – thus delivering a solution not much better than a “robo” platform, yet at a dramatically higher cost.

Is The Disruption Of The Traditional AUM Fee Schedule Just A Venture Capital Mirage?

Notwithstanding the near-term AUM fee pressure implied by today’s robo-advisor firms, the reality is that (most) advisory firms operate their fee schedules at healthy and sustainable profit margins, while none of today’s crop of robo-advisor firms are actually profitable.

Market leader Wealthfront, with approximately $1.5B of AUM, would generate less than $4M of revenue at its current fee schedule, hardly enough to cover the cost of its dozens of Silicon Valley engineers (one estimate pegged Wealthfront needing $7.3B of AUM just to break even). Competitor Betterment’s more-than-$1B of AUM similar would generate less than $3M of revenue at their fee schedule, also not enough to cover its 50+ (mostly engineer) employees.

Of course, this doesn’t necessarily mean the robo-advisor firms will go out of business anytime soon; Betterment has raised a total of $45M in capital to buy itself a long runway, and Wealthfront has raised almost $100M in just 2014 alone (and nearly $130M total) in venture capital. But it does raise the question of whether robo-advisors are pricing as they do simply because their fee schedule is actually below a sustainable level and is simply being subsidized by their available venture capital.

On the other hand, the reality may actually be that traditional advisory firm fees are “too high” simply because they are so small and undercapitalized that they’re not achieving enough economies of scale, and that advisory firms will ultimately need to band together and consolidate further to afford to drive their costs down to compete and better leverage their collective marketing capabilities. From this perspective, the “virtue” of the robo-advisors may simply be that they have received such an infusion of venture capital that they have been able to price from the start at the level they hope to ultimately reach after getting big, and are simply using their venture capital to bridge the gap from offering scaled pricing (and dealing with the high cost of client acquisition) and actually being sufficiently scaled to sustain it.

Nonetheless, the bottom line is simply this: while the final price point and business viability for robo-advisors remains uncertain, their pricing structure highlights a fundamental difference as to whether investment management is a low-price service upon which wealth management services are added, or a high-price service that receives “volume” price discounts at larger asset levels. The difference in the long run is about more than just what advisory firms can charge, but the entire basis of where the “value” is really added in the advisor-client relationship!

So what do you think? In the end, are advisory services something expensive that takes volume and scale to make cheaper, or is it something cheap that requires significant additional value-adds to charge a higher price? Is the distinction as simple as the difference between investment management and more comprehensive financial planning and wealth management services? Or are advisory firms actually just too small to compete with better-capitalized competition?

Michael,

You postulate a dichotomy between fees for investment management services and fees for wealth management services. To some degree these elements get blurred.

For example, toward which end of this dichotomy would you place the energy, time, relationship building good will, etc. that results in a client maintaining her balanced asset allocation (or,even better, selling bonds and buying stocks to rebalance) in March of 2009? As opposed to an investor who, facing a 30% drawdown, panicked out and never got back in.

Relatedly, it certainly can’t be that only the last, two hour, gut wrenching meeting in which the decision was taken gets attributed to the life altering difference between the two investors.

The point is if you only rely upon investment fees for your income you will have a problem. Two things. One, Robos all drive down investment fees just like discounters drove down transaction fees. Who is in that business today? Robos offer a definable standardized investment process with documented performance which only about 1% of advisors offer. Second, the firms don’t really care as they all have invasion policies for low fees. It is called a rock and a hard place. Advisors need to train themselves to capturing life events and all the ancillary products and services to generate income. Right now the average advisor is way over 98% investment fees. Future successful advisors it will be around 80%.

The real value of a financial advisor is to set up a sensible portfolio, help the client stay the course, and financial planning. I think the future of the industry is Robo advisor for a flat fee, plus hourly rate financial planning. This is the best deal from the client and gets away from the huge transfer of wealth that occurs with the AUM fee model.

Robo advisors are like turbo tax. They make sense for a certain demographic and personality type. But just like turbo tax didnt destroy the typical CPA firm, neither will Robo advisors.

Traditional investment advisers charging 80- 100bps for asset allocation and fund selection are facing a bleak future as the internet increasingly creates greater transparency and alternatives offering far better value.

I believe a flat fee structure at say 3 different levels – $5k per annum, $10k pa and $20k pa for increasingly sophisticated wealth management and planning iservices s the way forward – remove the link to assets and move to a real consultancy type service which avoids the inherent conflict of interest and cross subsidy prevalent in the bps model.

This describes the model we put in place at our firm (www.altiora.com). Thanks for confirming what we’ve had in mind for quite some time…

I prefer to look at this from my perspective (don’t know what other perspective I can look at it from!). I am trying to manage my own portfolio. Why? I feel that traditional investment advisers are not there for me, but are there for themselves. I worked for a large investment firm and all that mattered was asset growth-anyway that you could get it. The focus was not portfolio management or client returns. I also felt that the advisor was unable to help me achieve returns in excess of the indices. They didn’t have the skill. The stock pickers were generally the old school guys. More losers than winners. So what did that leave me? Buy the index-ETFs or find stocks to buy myself. Why did I need an investment advisor for that?

The robo-advisors have the right ingredients-disciplined investment approach, no particular incentive to churn your portfolio and robust software programs. But a couple that I have seen are not pure. They cross sell products into the funds from non-arm’s length investment management firm. They say they are not conflicted………….

What would work for me is a true systems based operator-transparent on ETF selection (say they restrict themselves to ETFs that are the lowest cost for the product they have in mind). But again, no judgement here on which ETF, otherwise bias sets in. So I need a robo-advisor who truly is on cruise control and tweaks my portfolio for asset allocation reasons. And the robo-portfolio only becomes one of my portfolios as my assets hopefully grow.