Executive Summary

For those in poor health who face potential estate taxes and have a large IRA, a popular tax strategy is the so-called “deathbed Roth conversion” where the IRA owner converts to a Roth before death as a means to pay the income taxes up front and reduce the size of his/her estate. For large estates (and large IRAs), the tax savings can be significant.

However, the caveat of the deathbed Roth conversion strategy is that in most cases it is unnecessary, thanks to the availability of the so-called “IRD” (Income in Respect of a Decedent) tax, which provides IRA beneficiaries an income tax deduction for any estate taxes paid by the original IRA owner. In fact, the whole purpose of the IRD deduction is to eliminate any need for deathbed conversions (or liquidations) of pre-tax assets, by aligning the tax deductions to ensure that the beneficiaries will be no worse off (nor any better).

On the other hand, it’s notable that while the IRD deduction does shelter against Federal estate taxes, deathbed Roth conversions can still be relevant to protect against state estate taxes. Though in either case, the greatest driver of the outcome is not actually the IRD deduction or minimizing state estate taxes at all, but trying to shift the timing of when the IRA is recognized for tax purposes, so that the income taxes are paid at whichever rate is lower – either the IRA owner now, or the rate the beneficiaries would pay by simply inheriting the pre-tax IRA and stretching it out in the future!

Deathbed Roth Conversions To Minimize Federal Estate Taxes

For those with a higher net worth – over the $5.43M (in 2015) estate tax exemption – a pre-tax IRA can be subject to significant cumulative taxation. Not only will the account be subject to income taxes someday at rates as high as 39.6%, but the IRA will also trigger estate taxes at a top rate of 40% as well!

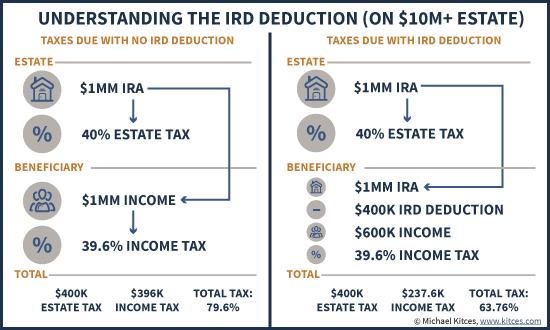

Example 1. An affluent individual has nearly $10M of net worth, including an IRA worth $1M. Being over the $5.43M estate tax exemption amount for an individual, the decedent’s estate will face an estate tax liability of 40% on the last several million dollars of net worth, including the IRA as a part. In addition, when the IRA is subsequently inherited by the next generation heirs, it is still a pre-tax asset that will be subject to ordinary income tax rates as high as 39.6% as the account is liquidated. The end result: at the margin, as much as 40% + 39.6% = 79.6% of the IRA may be diminished by a combination of income and estate taxes!

A popular strategy to at least partially mitigate this outcome for someone who faces the estate tax and has a significant IRA is to do a Roth conversion before death, possibly even as a “deathbed” conversion if the IRA owner is in poor health. The goal of the strategy is to trigger income taxes now – before death – which will reduce the size of the estate, and therefore reduce the amount of estate taxes that will be due.

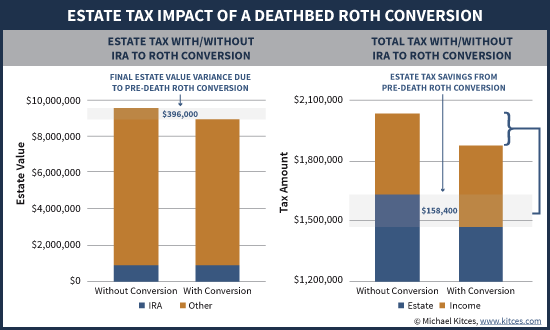

Example 2a. Continuing the earlier example, assume that the decedent’s estate had a gross value of $10M, including a $1M IRA. After all deductions, the net taxable estate was $9.5M. Given the current estate tax tables in effect, a $9.5M taxable estate would be subject to a tentative estate tax of $3,745,800, and after the $2,117,800 unified credit would lead to a final estate tax of $1,628,000. In addition, whenever the beneficiaries inherit the IRA in the future, they would still be subject to ordinary income taxation at a potential top rate of 39.6%, resulting in another $396,000 of taxes. The end result: the total estate is diminished by $2,024,000 of combined income and estate taxes, including $796,000 attributable directly or indirectly to the IRA ($400,000 in estate taxes at a 40% rate, plus $396,000 of income taxes).

Example 2b. To minimize the estate tax exposure, the client chooses to convert the IRA to a Roth now. Assuming the individual is already in the top tax bracket (given the overall wealth involved), the income tax liability on the Roth conversion will be $396,000, which reduces the remaining size of the estate to about $9.1M. Now when the individual passes away, the estate tax liability on a $9.1M estate is “only” $1,469,600, and when added to the $396,000 of income taxes previously paid, leads to a total tax burden of $1,865,600. The end result: the family saved $158,400 (the difference between $2,024,000 of total taxes in the prior scenario versus just $1,865,600 in this scenario) by choosing to do a Roth conversion before death. (Notably, the $158,400 of savings is precisely equal to a tax savings of 40% on the $396,000 of income taxes that were paid out and reduced the estate before death.)

The benefit of this strategy is that it essentially avoids the “double taxation” of paying estate taxes on an asset that will still owe income taxes in the future as well. Instead, by paying the income tax bill “up front” the value is removed from the estate, avoiding the second tier of taxation on those same dollars.

However, as it turns out, the strategy is also largely unnecessary, because it misses the fact that the beneficiary of an inherited IRA that was previously subject to estate taxes gets a special income tax deduction, called the Income In Respect of a Decedent (IRD) deduction under IRC Section 691(c)!

How The IRC Section 691(c) IRD Deduction Makes Roth Conversions Unnecessary For (Federal) Estate Tax Avoidance

As just shown, the cumulative impact of a 40% estate tax rate and a 39.6% top income tax rate can be severe. If either/both rates were even higher, the entire value of a pre-tax IRA could be wiped out at death. In fact, if the combined rates are greater than 100%, the possibility might exist that an IRA could cause more in taxes than the entire value of the IRA in the first place!

To avoid this potentially disastrous (and unduly burdensome) outcome, Congress created the “Income in Respect of a Decedent” (IRD) deduction under IRC Section 691(c), which stipulates that when an estate tax is paid on assets that include a pre-tax asset like an IRA, the beneficiaries receive an income tax deduction for any additional estate taxes that were caused by the IRA.

Example 3. Continuing the prior examples, since at the margin the $1M IRA caused $400,000 of estate taxes (at the 40% marginal estate tax rate), the beneficiaries will be eligible for a $400,000 income tax deduction when the IRA funds become taxable as they are subsequently withdrawn from the account. Given this deduction, the beneficiaries will only end out owing income taxes on $1M - $400,000 = $600,000 of the IRA. Which means even at a top 39.6% tax rate, the beneficiaries will only face $237,600 of income taxes on the $1M inherited IRA, or a marginal rate of 23.76%. The end result – thanks to the IRD deduction, the $1M IRA is “only” diminished by 40% + 23.76% = 63.76%, not the 79.6% that would have resulted by just adding the two taxes together.

Thanks to the IRD deduction, cumulative income and estate taxes can never consume more than the entire value of an IRA account. For instance, even if at the extreme the estate tax rate was 100% on the $1M IRA, it would mean the beneficiaries would get a $1M income tax deduction to fully offset the value of the account and owe no income taxes on the IRA. More generally, the IRD deduction ensures that the income and estate tax are never cumulative, and instead are sequential – you pay one, and then you pay the other on what’s left (if there is anything left).

Notably, though, the IRD deduction also means that the earlier Roth conversion strategy is actually unnecessary. There’s no need to pay income taxes up front (with a Roth conversion) to avoid subsequent estate taxes, because the IRD deduction provides that where estate taxes are paid, the income tax liability will be reduced to equalize the scenarios.

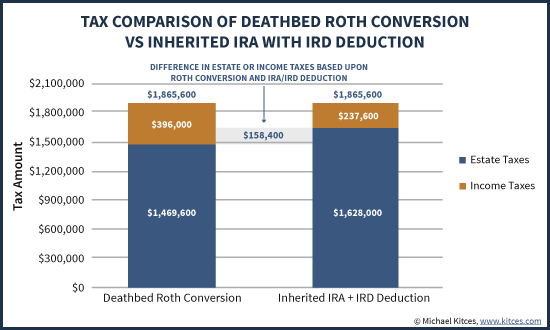

Example 4. In the earlier Example 2a, we showed how an IRA could be subject to both a 40% estate tax and a 39.6% ordinary income tax. However, with the IRD deduction, the results would be somewhat different. Recall earlier that the decedent’s estate had a gross value of $10M (including a $1M IRA), and a net taxable estate of $9.5M, such that the final estate tax liability was $1,628,000. In this situation, the beneficiaries would be eligible for an income tax deduction (the IRD deduction) for the extra $400,000 of estate taxes caused by the $1M IRA (as the IRD deduction always assumes that the IRA is the “last” asset taxed at the highest marginal estate tax rate). As a result, the income tax liability would be only $237,600 (which is 39.6% on the $600,000 value of the IRA after the IRD deduction), which means the combined taxes would be “only” $1,628,000 + $237,600 = $1,865,600.

Note that with the IRD deduction, the total amount of taxes due in Example 4 (where the IRA is inherited and the beneficiaries pay the income taxes after an IRD deduction) is exactly the same as the outcome in Example 2b (where the IRA is converted before death to reduce estate taxes). In point of fact, this is the whole purpose of the IRD deduction – it ensures that the two scenarios will be the same, whether the estate tax liability is reduced by a pre-death Roth conversion, or the income tax liability is reduced by a post-death IRD deduction.

How Relying On The IRD Deduction Can Beat Inheriting A Roth IRA

While the primary purpose of the IRD deduction is simply to “equalize” the outcomes between converting (or liquidating) an IRA before death versus inheriting it to be liquidated after, in reality the availability of the IRD deduction can make it even better to inherit a traditional IRA and not a Roth.

The reason is that while the tax outcomes are the same as long as the income tax rate remains constant (in the above examples, it was 39.6% in all cases), in situations where the beneficiaries will enjoy a lower tax rate the potential to bequeath an inherited IRA – and stack an IRD deduction on top – just makes the results even more appealing. Even though the IRD deduction will technically be “less valuable” – as it’s being deducted against a lower tax bracket – the fact that all the IRA withdrawals will be taxed at a lower rate still means the total tax exposure is lower.

Example 5. Continuing the prior example, imagine instead that the beneficiaries plan to stretch the IRA out over time, and the smaller systematic withdrawals mean the beneficiaries will only ever withdraw the IRA at an average tax rate of 25%. In this scenario, the estate tax liability will still be $1,628,000 and the IRD deduction will still be $400,000, but the total income tax liability will be only $600,000 (net value of IRA) x 25% (income tax rate) = $150,000. The end result: the beneficiaries actually finish with $87,600 more in total wealth, due to the lower tax rates available by liquidating the IRA in the hands of the beneficiary.

Of course, this scenario can swing both ways – if the original IRA owner would have been subject to lower tax rates and the beneficiaries are in a higher tax bracket, then it’s better to convert to a Roth before death (and take advantage of the lower rate). However, in situations like a “deathbed Roth conversion” where the goal is to convert everything all at once to rapidly diminish the estate before death, the sheer size of the Roth conversion itself (not to mention the net worth of the individual who’s subject to estate taxes in the first place) increases the likelihood that most or all of the conversion will be taxed at the top ordinary income rates. By contrast, when an IRA is bequeathed to the next generation – especially if the assets of the estate will be split amongst multiple beneficiaries so none of them will be as ‘wealthy’ individually as the original owner was, and the beneficiaries will stretch the IRA distributions after death to further smooth out the income tax exposure – there’s more potential for beneficiaries to be eligible for a materially lower tax rate.

Caveats To Relying On The IRD Deduction For An Inherited IRA

Notwithstanding the primary benefit of the IRD deduction – eliminating the need to convert to a Roth IRA before death, which at best produces an equal outcome and potentially a worse one if a large deathbed Roth conversion drives up the IRA owner’s tax bracket – there are some important caveats to be aware of as well.

The first is that ultimately the IRD deduction is an itemized deduction, which means it’s only helpful for beneficiaries who will be itemizing their deductions and not taking the standard deduction. Fortunately, the IRD deduction is not subject to a 2%-of-AGI floor (even though it’s otherwise a miscellaneous itemized deduction), and is not an AMT adjustment either (for the same reason), but it still only matters if the beneficiary’s total deductions merit itemizing in the first place. On the other hand, the reality is that the sheer size of the IRD deduction often means that it alone will be enough of a deduction to justify itemizing – though if the IRD deduction is what pushes the total deductions across the line for itemizing, that still means at least some of the benefit is lost.

Second, as noted earlier, the IRD deduction equalizes the outcomes when tax rates are equal, but it is generally still not worth pursuing the IRD deduction if the beneficiary will be subject to a higher tax rate than the decedent would have been. While doing a lump sum Roth conversion on a deathbed will often eliminate that benefit – as the lump sum conversion itself drives the original IRA owner into the top tax bracket – if the IRA can be whittled down over time with partial Roth conversions to diminish the tax exposure (and get the average rate of the Roth conversion below the tax rate of the beneficiaries) it is more worthwhile.

It’s also worth noting that with the ongoing calls for potentially eliminating the stretch IRA rules and requiring most beneficiaries to liquidate under the 5-year rule, there is also less opportunity for beneficiaries to be subject to lower tax rates and more potential for them to be pushed into higher brackets (as a large IRA may be ‘squeezed out’ rather quickly). Though technically, this really just makes the point that ultimately the IRD deduction is a benefit, but should still take second seat to the overall evaluation of whether the beneficiaries will have a higher or lower tax bracket than the original decedent considering a Roth conversion.

The Lack Of A 691(c) IRD Deduction For State Estate Taxes

A final important caveat to consider in relying on the IRD deduction to avoid the double-impact of income and estate taxation is that the IRD deduction applies only for any Federal estate taxes paid, and not for state estate taxes. As a result, when a state estate tax is involved, a deathbed Roth conversion really can save estate taxes at the state level.

Example 6a. Betsy has a net worth of $3M after all estate tax deductions, including a $500k IRA, and lives in a state that applies a 16% estate tax on all assets above a $1M exemption amount. If Betsy simply leaves all these assets outright to her heirs, she’ll owe $320,000 of estate taxes (16% of the excess above $1M), and at an average tax rate of 33% the heirs will pay another $166,667 of income taxes (with no IRD deduction), for total taxes due of $486,667.

Example 6b. By contrast, if Betsy converts her IRA now at an average tax rate of 33%, she will pay $166,667 in income taxes, reducing the size of her estate by that amount. In turn, this means her total state estate tax liability will be only $293,333, for a total tax liability of $460,000. The end result: Betsy’s family saves $26,667 of taxes by doing a deathbed Roth conversion (equal to the 16% state estate taxes not paid on the $166,667 of income taxes triggered by the Roth conversion).

Notably, even in the above example, the family’s outcome was improved “only” because of the assumption that the heirs will pay the same average tax rate of 33% on the inherited IRA as Betsy was paying on the Roth conversion. If the Roth conversion drives up Betsy’s ordinary income tax rate, a trade-off now occurs – the family gains by the 16% of state estate taxes avoided, but loses by the increase in the income tax rate. And notably, the change in income tax rates impacts the whole IRA, while the estate tax savings is only 16% of the Roth conversion tax bill in the first place. Thus, a relatively modest income tax rate change can still wipe out most of the estate tax savings of the strategy.

Example 6c. Continuing the prior example, if Betsy’s heirs could have inherited the IRA and liquidated it at “just” 28% (a tax rate savings of 5% on the value of the IRA), the heirs would pay only $140,000 of income taxes, plus the $320,000 of estate taxes already paid, for a total tax liability of $460,000. Notably, this is exactly the same as the total amount of taxes paid in example 6b where Betsy converted to a Roth before death! In other words, a 5% change in income tax rates on the whole IRA was equal to a 16% estate tax savings on the taxes avoided by the Roth conversion!

Given these trade-offs, doing a deathbed Roth conversion to avoid state estate taxes will generally only be favorable in situations where the conversion does not drive the IRA owner into a materially higher tax bracket than the beneficiaries. And of course, the scenario is only relevant in the subset of states that have a state estate tax in the first place (a list of states that has been declining as more and more states feel the pressure to either recouple to the Federal estate tax, or repeal altogether).

Nonetheless, it’s crucial to recognize that the IRD deduction is only applicable against Federal estate taxes, and that when state estate taxes are involved, a deathbed Roth conversion can still be an effective tax strategy, at least when all else (i.e., marginal tax rates of the IRA owner and beneficiaries) remains equal!

So what do you think? Have you ever advised clients to pursue a “deathbed” Roth conversion to minimize estate taxes? Have you ever used the approach as a means to minimize state (as opposed to Federal) estate taxes? Would you reconsider the strategy going forward depending on the income tax brackets of the IRA owner and the anticipated beneficiaries?

Great article! What do you think about those with large IRAs and large estates donating the IRAs to their family foundation and naming their beneficiaries to be the directors of that foundation. This would allow the beneficiaries to draw appropriate salaries from the foundation and name their children to be their successors.

An interesting INCOME TAX use of deathbed Roth conversions is for someone with a reverse mortgage that has been in place for a while. There will likely be substantial mortgage interest built up, and paid off when the reverse mortgage is paid off, in this scenario after the homeowner has passed away. There has always been the consideration of whose tax bracket is lower – the deathbed person or heirs. This is a related, but different approach, and avoids losing the tax deduction on the reverse mortgage. There are several considerations, including is this acquisition or home equity debt, and getting the translations in the same tax year. As far as I know, this is a previously unexplored strategy. For an extended analysis, see http://toolsforretirementplanning.com/2015/12/14/recover-lost-tax-deduction/ for work by a tax attorney on this issue.