Executive Summary

While the use of pensions as an employee benefit is on the decline, many of today’s workers nearing retirement have participated in a pension plan for the past several decades, and have already accumulated a significant pension benefit. And as those individuals begin to retire, they are faced with the classic decision of whether to keep the lifetime pension payments, or choose a lump sum instead.

While there are several factors that go into the pension-vs-lump-sum decision, ultimately the trade-off can be boiled down to calculating the internal rate of return (IRR) of the promised pension cash flows, which reveals the “hurdle rate” of return that a lump sum portfolio would have to earn to generate to reproduce those same payments over the same time horizon. Of course, the longer the retiree is expected to live, the greater the number of anticipated pension payments, and the greater the portfolio hurdle rate will be.

Ultimately, though, because life expectancy will vary by the individual, and in practice the size of a lump sum relative to a pension payments will also vary from one plan to the next (and also over time, as the GATT rate used to discount the pension payments fluctuates from month to month and year to year), the decision of whether to keep a pension or convert it into a lump sum will vary from one person to the next. In some cases, choosing a lump sum will clearly be best (e.g., when life expectancy is short or the hurdle rate is especially low), while in others there will be no way for a portfolio to generate similar cash flows without a significant amount of risk – at least, as long as the pension plan itself remains secure and isn’t facing a potential default or being forced to rely on PBGC backing!

Pension Versus Lump Sum Decision

Retirees who are eligible for a pension are often offered the choice of whether to actually take the pension payments for life, or instead to receive a lump sum dollar amount for the “equivalent” value of the pension – with the idea that the retiree could then take the money (rolling it over to an IRA), invest it, and generate his/her own cash flows by taking systematic withdrawals throughout retirement.

The upside of keeping the pension itself is that the payments are guaranteed to continue for life (at least to the extent that the pension plan itself remains in place and solvent and doesn’t default). Thus, whether the retiree lives 10, 20, or 30 (or more!) years in retirement, he/she doesn’t have to worry about the risk of outliving the money.

By contrast, selecting the lump sum gives the retiree the potential to invest, earn more growth, and generate even greater retirement cash flows… and if something happens to the retiree, any unused account balance that remains will be available to a surviving spouse or heirs. On the other hand, if the retiree fails to invest the funds for sufficient growth, there’s a danger that the money could run out altogether, and that a long-lived retiree may regret not having held on to the pension’s “income for life” guarantee.

Ultimately, though, whether it is really a “risk” to outlive the guaranteed lifetime payments that the pension offers by taking a lump sum depends on what kind of return must be generated on that lump sum to replicate the payments. After all, if the reality is that it would only take a return of 1% to 2% on that lump sum to create the same pension cash flows for a lifetime, there is little risk that the retiree will outlive the lump sum even if withdrawing from it for life. However, if the pension payments can only be replaced with a higher and much riskier rate of return, there’s also a greater risk those returns won’t manifest and the retiree could run out of money.

Calculating The Internal Rate Of Return (IRR) Of A Lifetime Pension

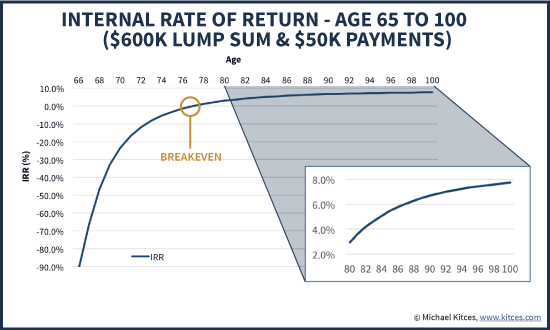

The necessary return that must be earned on a lump sum to replace the payments of a pension will depend on how long the pension payments are anticipated to last. After all, if the retiree passes away after just a year, technically even a -90% investment loss would still leave more money behind than taking the pension and having all payments cease in a year! On the other hand, for a retiree who lives to age 90 and beyond, collecting decades’ worth of payments, it may take a more significant return just to ensure the portfolio keeps up with what the pension would have guaranteed in the first place.

For instance, imagine that Jerry, a 65-year-old male, is eligible for a pension of $50,000/year (on his life only), or he can receive a lump sum payment of $600,000. How does Jerry choose?

Just looking at the simple math of the situation, if Jerry selects to keep his pension, it will take him 12 years just to get back the original lump sum he could have had on day 1 (where $50,000/payment x 12 payments = $600,000 lump sum). Of course, had he actually taken the lump sum, he would have been able to invest the money over those intervening years – which means even if he was actually taking $50,000/year all along, there would likely still be some money left over after 12 years as well (due to the growth on the remaining account balance as it was being spent down).

However, if Jerry lives to his (single male) life expectancy of age 82 – receiving payments for 17 years – his cumulative payments will add up to $850,000, spread over 17 years. By contrast, Jerry would have had to invest the lump sum at a 4.2% annualized growth rate for all those years to generate the same $850,000 of cash flows over time. In other words, if Jerry had taken the $600,000, withdrawn $50,000/year from it, while growing the remaining balance at 4.2%/year, he could have re-created the same cash flows for 17 years that the pension provided. Notably, Jerry “only” needs a 4.2% return, even though the pension is paying out $50,000/year on a $600,000 value (which is 8.3% of the account balance), because the reality is that a significant portion of each payment is not actually growth but simply a return of the original $600,000 principal; this is why it’s necessary to calculate an internal rate of return that accounts for both the growth and return-of-principal payments inherent in a pension payout.

Or viewed another way, by calculating the internal rate of return of the cash flows, we can determine the required rate of return - in essence, a "hurdle rate" of return - that Jerry would have to achieve over any particular time horizon for his lump sum such that withdrawals from the lump sum principal-plus-growth can replicate the same payments that the pension was providing for that same time period. The longer the time period, the more pension payments there are, and the higher the return Jerry must invest for - and actually achieve in the portfolio - in order to generate those same pension-equivalent cash flows as portfolio withdrawals from a $600,000 lump sum.

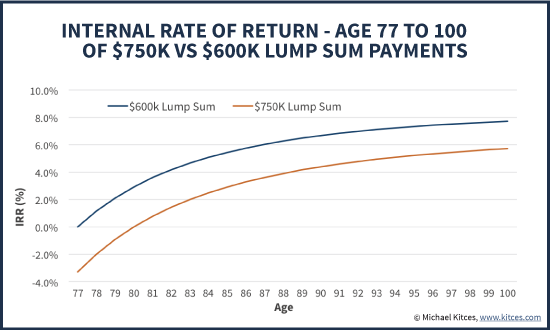

As the chart reveals, in this particular scenario the required rates of return to replicate what the pension provides are fairly modest in the early years, but get significant in the later years. To secure the pension payments until age 90, Jerry would need his portfolio to generate a 6.7% return. If Jerry lives to 100, he would have needed to grow the money at 7.7%/year to get the same $50,000/year-for-35-years payments that the pension was going to provide anyway.

In essence, then, the decision about whether or not to keep a pension is a form of risk/reward trade-off. If Jerry lives a long time, he gets a rather healthy implied rate of return for his lump sum – especially given that the pension payments are fixed and not subject to market volatility – but the value of those long-term returns are offset by the fact that if Jerry dies sooner rather than later, it can be the equivalent of losing 25%, 50%, or even 90% of the account value (as the pension payments can cease at death, even if only 1 payment was ever made!).

Lump Sum Vs Joint Survivor Pension Payouts

When it comes to a married couple, the dynamics of evaluating a (joint and survivor) pension versus a lump sum payout are slightly different.

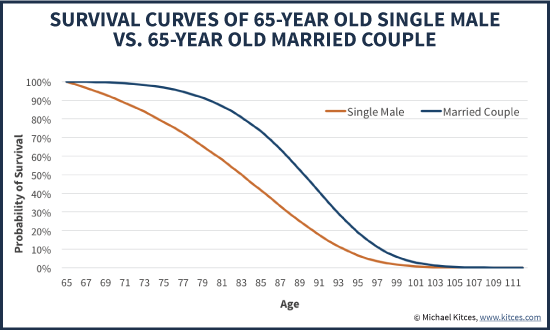

The good news is that with a joint pension, payments can continue for the lives of two spouses, and as long as either is alive, the payments can continue. This increases the likelihood that payments will continue, and reduces the risk of a ‘catastrophic’ loss where an untimely early death causes most or all of the value of the pension to be lost. For instance, the chart below shows the anticipated survival rate of a single 65-year-old male, versus the joint survival rate of a 65-year-old married couple. Simply put, the odds of both people passing away is much lower than either one individually, so the survival rates of a married couple are much higher (and life expectancy is much longer) than for an individual.

The bad news, however, is that pension providers also realize that there is a greater likelihood of making payments for a longer period of time with a joint pension payout – which is why the amount of the pension payments is typically reduced for joint and survivor pension payouts. For instance, continuing the earlier example, if Jerry’s pension offers a $50,000/year payment for the rest of his (individual) life, the payment might be reduced to $40,000/year as a joint payment over the combined lives of Jerry and his spouse.

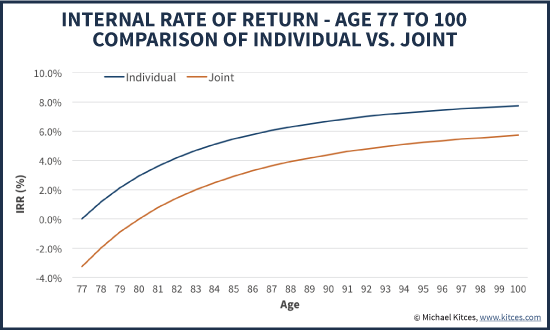

In this joint pension scenario, the couple will now require 15 years of payments just to recover their principal (instead of only 12 years), though ultimately if they live to their (joint) life expectancy of age 88 (in 23 years), the internal rate of return is still about the same as the individual scenario (right around 4%). In other words, if the couple lives to their life expectancy, the required rate of return on the pension lump sum to replicate the pension payments is similar. But the couple has to live much longer just to reach life expectancy and get the similar internal rate of return as the individual payment, because the payments are already adjusted down in the first place in recognition of the higher survival probabilities of the couple.

Notably, the fact that the joint pension payout is inherently less risky over the time horizon means there’s also much less upside in the long run. As shown in the chart above, even when the couple lives into their 90s and out to age 100, the implied rate of return of the pension payments is diminished by the fact that there is a greater likelihood of the couple living that long in the first place!

Pension Maximization And Evaluating Pension Versus Lump Sum Trade-Offs

The challenge of trying to maximize the value of a pension is that ultimately, the “best” strategy will depend most heavily on the anticipated time horizon (i.e., anticipated life expectancy). Over short time horizons (i.e., an untimely death in the early years), taking a pension can result in outright “losses” compared to just selecting the lump sum, receiving a few payments, and then having the remainder left over (of course, some pensions offer "period certain" guarantees that ensure a certain number of payments are made, which reduces the downside risk, but at a 'cost' of getting smaller payments if the pensioner does survive!). On the other hand, over long time horizons (i.e., those who live well past their life expectancy), a lump sum might have to generate a relatively high rate of return (with all the risk that involves) just to keep up.

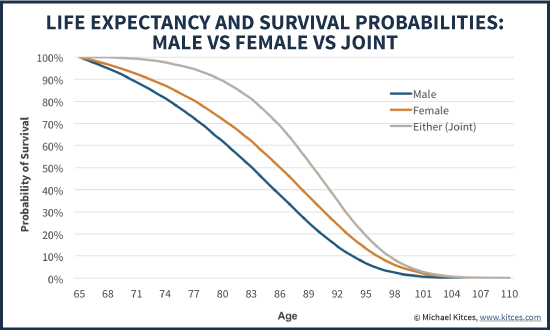

The fact that time horizon is so material means that first and foremost, the key factor to consider when evaluating pension-versus-lump-sum strategies is the anticipated life expectancy of the retiree. As a starting point, retirees can at least look at general life expectancy tables, and see at least the probable time horizon over which pension payments might be received. The chart below shows survival probabilities for a single male, a single female, and the joint survival probability that at least one of the two members of a couple are still alive.

In some cases, a retiree may have reason to know that his/her life expectancy situation will likely vary from the general case. Perhaps the retiree already has some health complications that will reduce anticipated life expectancy, tilting towards the decision to take a lump sum. Or perhaps the retiree has longevity in the family – and is still caring for two parents in their 90s! – suggesting that his/her own life expectancy may be well above average. Notably, being above-average income/wealth alone tends to be correlated with a life expectancy a few years beyond that of the general population.

Notably, though, while poor life expectancy significantly tilts the scales in favor of taking a lump sum, above-average life expectancy doesn’t necessarily mean that a pension will always be better. In some cases, the issue may be that one person’s life expectancy in a couple is above-average, but the other’s is not; in such cases, it may be better to take the single life pension payout, and buy life insurance with some or all of the higher payments, to protect the second spouse (a strategy often called “life insurance pension maximization” or “pension max” for short).

The biggest caveat for why a long life expectancy doesn’t always make a pension the winning choice is simply because some pensions have lump sums so “generous” that it is still relatively easy to generate a rate of return superior to the “hurdle rate” of the internal rate of return, even over a long payout time horizon. For instance, if Jerry’s pension offered a lump sum of $750,000 instead of just $600,000, the internal rates of return would be low enough that even if he lived under his 90s, a long-term investment portfolio would likely beat the required return threshold (and usually by a significant margin). Ironically (or perhaps not), the more generous the lump sum is up front, the more incentive there is to just take the lump sum, because it doesn't take much of a return on that lump sum to generate comparable pension-like payments from a portfolio.

The Discount GATT Rate And Determining The Size Of A Pension Lump Sum

So what determines the size of a pension lump sum, and the associated internal rates of return? Ultimately, it comes down to the factors that each individual pension plan uses to calculate the conversion of its pension into a lump sum, including plan’s own life expectancy assumptions (which may be more or less favorable than the general population life expectancy tables), and the plan’s “discount rate” (the rate of return used in the plan calculations to calculate the lump sum amount).

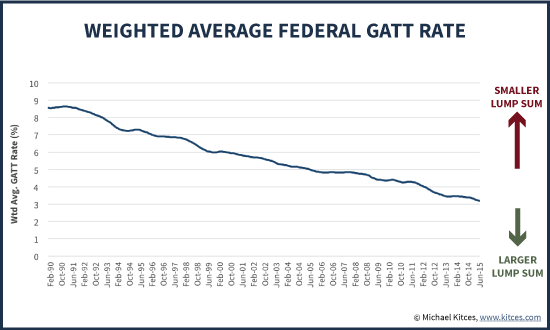

The discount rate in particular is significant, because in higher interest rate environments, the higher discount rate translates directly to a higher internal rate of return that must be achieved, and similarly means that the lump sum pension amounts shrink; as a result, it becomes harder and harder to replicate the pension payments with a portfolio-plus-growth in higher rate environments. By contrast, though, lower discount rates will be associated with larger lump sums… which means in today’s lower interest rate environment, the discount rates have been especially favorable for producing larger lump sums that have easier-to-clear hurdle rates for the portfolio. For instance, the chart below shows the Federal GATT (General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade) rate, commonly used in many pension plans to calculate pension lump sums, which is at historic lows right now.

As the chart shows, with GATT rates at historic lows, pension lump sums will tend to be higher – resulting in personalized internal-rate-of-return targets that may be easier to achieve with a retiree’s portfolio. Though ultimately, the analysis of whether to take a pension or lump sum must still be done on an individual basis, taking into account not only the internal rates of return the lump sum must reach to match the pension, but again the retiree(s) and their own health and life expectancy.

And of course, in today’s environment where many private pension plans are underfunded, some retirees simply may not want to take the risk that the pension payments could be limited if the pension plan defaults. While the Pension Benefit Guaranty Corporation (PBGC) does provide backing to most corporate pension plans, the current maximum pension benefit the PBGC backs is “only” $60,136/year for an individual ($54,123 for a joint-and-50%-survivor payout), which means retirees with larger pensions could still be at risk for part of their payments. And sadly, many states have pension plans that are even more underfunded, and in the case of state/local government pensions, there is no PBGC backing at all. In these situations, retirees may wish to take a lump sum and the associated investment risk because it’s more appealing than the risk of the pension plan itself. In other words, pension payments may not be volatile like markets from day to day and year to year, but they can still have a material risk in some circumstances.

The bottom line, though, is simply this: the decision of whether to take a pension or lump sum is ultimately driven by the retiree’s ability to use the lump sum to re-create what the pension would have paid anyway. Depending on the retiree’s life expectancy, and the implied internal rate of return of the pension payments relative to the lump sum (and presuming the retiree can implement that lump sum portfolio investment appropriately, with the advisor's help), it may be relatively easy to create a comparable portfolio return to replace the pension payments, or not. The only way to know is to evaluate each, one by one!