Executive Summary

Proper tax planning for clients relies on understanding what the tax consequences will be for various tax strategies - in other words, what tax rate, at the margin, will apply to the next dollar of income or deductions. Whether it's taking advantage of charitable deductions, calculating the true after-tax cost of tax-deductible interest, of evaluating the consequences of a Roth conversion, it's crucial to know how the client's tax liability would be impacted, on top of the existing "base" income that already exists, if the planning strategy is implemented.

However, for tax strategies that shift the timing of income - most notably, decisions like to whether to a traditional or Roth retirement account (or whether to convert from traditional to Roth) - it's important to evaluate not only the current marginal tax rate, but also the one that will apply in the future. After all, if the reality is that a Roth conversion accelerates income from future (tax rates) to the present day (tax rates), it's crucial to know whether today's tax rates are actually likely to be lower - or higher - than they would have been down the road!

While the conceptual process for determining a marginal tax rate is fairly straightforward - the tax rate that will apply at the margin after accounting for the underlying base income - the situation is much more complex in light of the various factors that impact marginal tax rates beyond just the client's tax bracket itself. The situation is further complicated by how inflation will change tax brackets in the future, and compounding growth can change the income and wealth picture as well. Nonetheless, it remains crucial to make reasonable estimates of how a client's tax situation will change over time, or it's impossible to make good tax planning decisions!

Measuring The Current Marginal Tax Rate

The basic concept of the marginal tax rate is relatively straightforward – it’s the tax rate that will apply, at the margin, to the next incremental amount of income (or deductions). In other words, if some base income amount is filling the lower tax brackets, such that earning an extra $1,000 of income will trigger an extra $250 of taxes, the marginal tax rate is $250 / $1,000 = 25% (regardless of how much in taxes was or wasn’t paid on the underlying base income up to that point). While an effective tax rate might tell you what portion of a client's overall income is being allocated to taxes, the marginal tax rate is the guide for - at the margin - what the benefit would be of a particular tax planning strategy.

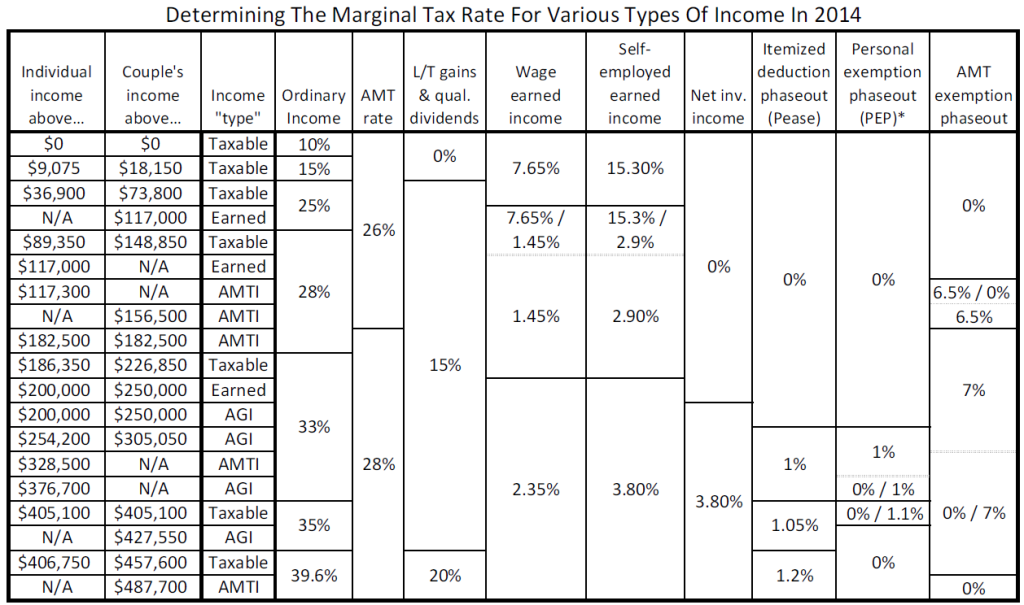

In practice, though, determining a marginal tax rate is far more complex, because the factors that cause additional taxes as income rises go far beyond just looking up a client’s current tax bracket. For instance, with larger amounts of marginal income, the client could actually be forced into a different tax bracket by income itself!

Example 1. A married couple with $130,000 of taxable income (after deductions) is in the 25% tax bracket. If this couple decides to do a $30,000 Roth conversion, their taxable income will rise to $160,000, putting them into the 28% tax bracket. However, the reality is that the marginal tax rate on this Roth conversion is not really 25% nor 28%; it’s actually 26.1%, as the first $18,850 of income will be taxed at 25% (to the top of the 25% bracket) and the next $11,150 will be taxed at 28%, for a total additional tax liability of $4,712.50 + $3,122.00 = $7,834.50 on $30,000 of income (where $7,834.50 / $30,000 = 26.1%).

However, the reality is that in today’s environment, tax brackets are a poor estimate of marginal tax rates, not only because large amounts of income may span multiple brackets, but also because brackets alone fail to account for the impact of changes in income can have on deductions themselves.

Example 2. A married couple has $230,000 of ordinary income from wages and $50,000 of long-term capital gains, and is trying to understand what the marginal tax rate would be to determine whether to contribute $10,000 to a traditional 401(k) or a Roth 401(k). The couple pays in $20,000 of mortgage interest, $15,000 of investment management fees, and will claim two personal exemptions (for husband and wife).

With a traditional 401(k) contribution, the couple’s ordinary income will be reduced to $220,000 (and AGI will be $270,000). Against their ordinary income, they will be able to claim a $20,000 mortgage interest deduction, and $9,600 of miscellaneous itemized deductions (the excess of $15,000 of investment management fees over the 2%-of-AGI threshold), and $3,950 x 2 = $7,900 of personal exemptions, resulting in ordinary income of $182,500 and a tax liability of $38,347. On top of this, they will pay 15% in capital gains taxes on $50,000 of capital gains (or another $7,500), and because their AGI is $270,000, they will owe a 3.8% Medicare surtax on the last $20,000 of long-term capital gains (an extra $760 of taxes). Ultimately, this means the couple will pay $38,347 + $7,500 + $760 = $46,607 of taxes.

If the couple contributes to a Roth 401(k) instead, their ordinary income will still be $230,000 (and AGI will be $280,000), resulting in another $2,800 of taxes given their 28% tax bracket. In addition, given their higher AGI, they will only be able to deduct $9,400 of investment management expenses (with the higher 2%-of-AGI threshold), resulting in $200 of lost deductions at their 28% tax bracket and another $56 of taxes. Furthermore, with a $280,000 AGI, they will now face $30,000 of long-term capital gains over the 3.8% Medicare surtax threshold, leading to another $10,000 x 3.8% = $380 of Medicare taxes. Thus, the net result of their extra $10,000 of income is an extra $2,800 + $56 + $380 = $3,236, or a marginal tax rate of 32.36%!

The end result of this example is that, even though the couple is in a 28% “tax bracket”, their marginal tax rate on another $10,000 of income is actually 32.36%, given the impact of more income on the miscellaneous itemized deduction 2%-of-AGI threshold, and also the amount of capital gains that cross the 3.8% Medicare surtax threshold!

In fact, the reality is that additional increases in income can trigger taxation far beyond just the tax bracket itself, including the impact of income on deduction thresholds (e.g., medical expenses and miscellaneous itemized deductions), the phaseout of itemized deductions and personal exemptions at higher income levels, the phaseout of various tax credits as income rises (e.g., the premium assistance tax credit), the impact of the AMT and the phaseout of the AMT exemption, the introduction (in 2013) of two new Medicare taxes (a 3.8% tax on net investment income and a 0.9% tax on earned income), and the special rates that apply to long-term capital gains and qualified dividends (which now have their own 0%, 15%, and 20% three-tax-bracket system!).

For older clients, higher income levels can also phase in the taxation of Social Security benefits, and trigger higher income-related adjustments to Medicare Part B and Part D premiums (which are also indirect increases in the marginal tax rate)! Because of all these overlapping effects, in some cases the best way to estimate a client's marginal tax rate is simply to use tax planning software, enter the client's existing details, and then simply add $1,000 (or some other modest amount of arbitrary income) and see how the tax rate changes. If adding $1,000 of income increases the tax liability by $313 in the software - which takes everything into account - the end result is that the client's marginal tax rate is $313 / $1,000 = 31.3%. By adding more income in $1,000 increments, you can identify transition points where the client's marginal tax rate is changing (e.g., for any of the numerous factors listed above).

Thus, to truly calculate a current marginal tax rate, best practices really requires calculating a client’s total tax liability twice – once without the marginal income, and once with it added in – to ensure that all of these factors are properly accounted for, especially since having several factors overlap at once can lead to a significantly higher marginal tax rate than just what would be implied by the tax bracket alone! Notably, though, properly determining a marginal tax rate requires first recognizing that all the income the client has already earned is “baked in” to the calculation already; the point is not to calculate the tax liability on all the income, but just to calculate the additional taxes (or tax savings) on the next segment of income.

Estimating A Future Marginal Tax Rate

In principle, calculating a marginal tax rate for future income is the same as in the present – evaluate how the tax obligation changes as, at the margin, income is added or subtracted from the base amount of income that will already be present.

For instance, imagine that you’re trying to estimate the marginal tax rate of a client in retirement, to determine whether it would be better to do a Roth conversion now in their late 50s while they’re still working, or 10 years from now when they’ll be in their late 60s and have already retired. Given that the best deal for the traditional versus Roth decision is to pay taxes whenever the marginal tax rate will be lowest, comparing the current marginal tax rate to whatever the future rate is estimated to be is crucial. Factors to consider would include:

- Taxable accounts may be generating some ongoing interest, dividends, and capital gains

- Wages will be gone, but pensions may have started

- The client may need to take some IRA withdrawals to sustain lifestyle (and will face Required Minimum Distributions eventually)

- Social Security benefits (and the potential taxation of Social Security benefits) will begin at some point

Given some assumptions about these factors, the client’s marginal tax rate can be determined, to evaluate the consequences of leaving the money in traditional IRA form (to be withdrawn later at the marginal tax rate) or converted (to be taxed at the current marginal tax rate).

Example 3. The retired couple is assumed in the future to have $60,000 in pension income, $40,000 in Social Security benefits, $15,000 of interest income, and $20,000 of qualified dividends and long-term capital gains. By then, the couple will have paid off their mortgage, and with little in the way of other deductions will claim the standard deduction (as charitable deductions and investment management fees alone will not be large enough to exceed the standard deduction threshold). Given their income – and the fact that the maximum 85% of Social Security benefits will be taxable – their AGI will be $60,000 + 34,000 + 15,000 + $20,000 = 129,000, and after exemptions and the standard deduction will fall within the 25% tax bracket. Thus, to the extent the couple plans to take IRA withdrawals in retirement, their future marginal tax rate will be 25% (at least until/unless they take out so much in future IRA distributions that it drives up their tax bracket and the marginal tax rate!).

Notably, the couple’s marginal tax rate in the example above will be 25%, even though the reality is that their actual tax liability (at least with today’s brackets) would be only $11,627. As a result, their effective tax rate would only be approximately 8.6%. Nonetheless, whether the couple converts the next $10,000 (or $50,000, or whatever) of IRA income, the reality is that the 10% and 15% brackets will already be filled by the other income already noted, which means any additional income on top of what they’re already projected to have will be accumulating at a 25% rate. Thus, given that $129,000 of AGI is the couple’s base income, and the deductions they’re anticipated to have, 25% is the proper marginal tax rate!

Projecting Tax Rates Into The Future

In practice, the added complexity of projecting a future marginal tax rate is that some consideration must be given for how inflation adjustments (to the tax brackets and potentially to income) and growth (to portfolios that generate income and distributions) may impact the future scenarios. For instance:

- Tax brackets themselves are adjusted annually for inflation; as a result, the threshold for higher tax brackets will rise over time. (In fact, with moderate inflation, the couple in the example above may actually dip down into “just” the 15% tax bracket as the threshold for the 25% bracket is adjusted higher for inflation!)

- Income streams may adjust higher with inflation, including Social Security and (potentially) pension payouts.

- Investment accounts will grow, and a large investment portfolio inevitably means a higher average amount of interest, dividends, and capital gains in the future

- Compounding growth in an IRA can lead to larger account balances, which ultimately drive more taxable income upon withdrawal and/or trigger larger RMDs when they begin at age 70 ½. (Conversely, significant Roth conversions in early years can so whittle down the size of an IRA balance that there is actually less IRA income in the future!)

Notwithstanding the added complexity of projecting into the future, though, the fundamental point remains the same: to estimate a future marginal tax rate (to compare it to today), it’s necessary to first determine what the “base” income will be, that unavoidably will fill up some portion of the lower tax brackets, and then determine what tax rate will apply, at the margin, to the income on top. In reality, this is simply the same approach as is used to determine a marginal tax rate today – determining what additional taxes will apply, at the margin, on top of the base income that’s already projected – but it’s especially important to recognize the factors that may increase, or decrease, base income and the associated marginal tax rate in the future! Yet at the same time, with an increasingly complex tax system, it’s crucial to account for all the factors that can impact the marginal tax rate, now and in the future, and not just focus on tax brackets alone!

(Michael’s Note: For those who need some additional help doing these types of analysis, you may wish to check out BNA Income Tax Planner, a robust tax planning tool that’s especially good for doing multi-year side-by-side comparisons of tax strategies! Although notably, even BNA has some limitations in its ability to project multiple decades out into the future!)