Executive Summary

Although numerous tax-advantaged vehicles are available for retirement savings, Health Savings Accounts (HSAs) have particular benefits for individuals saving for retirement. Specifically, HSAs offer a "Triple Tax Benefit" that includes tax-deductible contributions, tax-deferred growth, and tax-free withdrawals for qualified medical expenses. This can allow individuals to save a significant amount that can be withdrawn tax-free for medical expenses later in retirement. Therefore, for workers looking to boost their savings towards the end of their working years, HSA contributions can be the most tax-efficient vehicle available.

The caveat, however, is that to be eligible to contribute to an HSA, an individual must be covered by a qualifying High-Deductible Health Plan (HDHP) with no other non-HDHP coverage. And because government-funded health insurance options such as Medicare are not considered qualifying HDHP coverage, enrolling in Medicare – either directly through its website or by applying for Social Security benefits (which automatically enrolls someone in Medicare once they reach age 65) – means that an individual will no longer be eligible to contribute to an HSA.

For retirees, self-employed workers, and others who rely on Medicare as their sole option for health insurance after reaching age 65, this means there is effectively no way to contribute to an HSA after age 65. However, people who continue working beyond age 65 (or whose spouse does so) and have access to an employer-provided HDHP can continue making HSA contributions as long as they don't enroll in Medicare or apply for Social Security benefits. And because there's no age cap on HSA contributions, it's possible to keep contributing for as long as the person is still working and remains on a qualifying HDHP (although retiring and subsequently enrolling in Medicare will ultimately end HSA eligibility).

Advisors can help their clients who want to keep contributing to HSAs after age 65 by planning strategies that help to preserve their eligibility and maximize the amount they can contribute. For instance, if someone has applied for Social Security benefits and inadvertently enrolled in Medicare (which would make them ineligible for HSA contributions), they may be able to withdraw their Social Security application within 12 months and cancel their Medicare coverage to restore their eligibility – although doing so would require paying back any Social Security benefits actually received.

Additionally, when married couples have one spouse with HDHP coverage, the other spouse can enroll in Medicare without affecting the HDHP-covered spouse's HSA eligibility (and if the HDHP covers both spouses, one spouse can still contribute up to the higher family contribution limit even if the other spouse is covered by Medicare and ineligible to contribute to their own HSA).

And when someone working past age 65 does decide to retire, they will need to navigate the "6-month rule", where Medicare coverage is considered to begin 6 months before applying for benefits. This means the individual will need to plan carefully to calculate their maximum allowed HSA contribution to avoid inadvertently overcontributing to their HSA, since they may become ineligible for contributions well before they actually retire and apply for Medicare!

The key point is that while it's possible to contribute to an HSA after age 65, the specific rules around HSAs and Medicare introduce an additional layer of planning that's needed once an individual crosses the age-65 threshold. But given that the point of working past 65 is often to boost retirement savings, and given the tax-efficient benefits of HSAs as a retirement savings vehicle, the extra planning can ultimately be worthwhile on account of the additional tax-free savings for those who can navigate the challenges of doing so!

Age 65 has been considered the default age for retirement in the United States going back nearly a century, with the Social Security Act of 1935 setting 65 as the universal retirement age (although numerous state and private pension systems had also used 65 as the age where retirement benefits were triggered even earlier than that). When Medicare was introduced in 1965, it also used 65 as the age at which people qualified for government-provided health insurance benefits.

Over the decades, however, a series of developments – including the raising of the eligibility age for full Social Security benefits to age 67, as well as the broad replacement of defined benefit pension plans with defined contribution savings plans as the standard workplace retirement plan option – have eroded the notion of 65 as the 'normal' retirement age, even though the cutoff date for Medicare coverage remains at 65 and many retirement calculators and financial planning software platforms still use 65 as the default retirement age. In reality, more and more people have been opting to continue working beyond age 65: According to Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) data, the proportion of adults aged 65–74 who were working or looking to work increased from 20.4% in 2002 to 26.6% in 2022, and is projected to increase further to 29.9% by 2032.

People have many reasons for wanting to work beyond age 65, from the sense of purpose that work brings into their lives to the social relationships it provides to the simple desire to have an ongoing routine from day to day. But one of the most common reasons that people continue to work is the desire to better set themselves up financially for retirement. Many consider those last few working years as a final opportunity to boost their savings and alleviate fears of outliving their retirement savings (especially as lifespans have grown on average since the days when 65 was the default retirement age, requiring one's savings to be stretched over a greater number of years). A few more years of earning income gives workers one last chance to top off the tank, as it were, and feel more secure in their financial situation going into retirement.

The Benefits Of Building HSA Savings For Retirement

Workers have many options for building their savings in the years before retirement, from workplace 401(k) plans to tax-advantaged plans like traditional and Roth IRAs to standard taxable brokerage accounts. But one of the most powerful tax-advantaged savings vehicles that one can contribute to during their working years is the Health Savings Account (HSA).

For eligible individuals, HSAs have 3 key tax benefits:

- Contributions to the HSA are tax-deductible for eligible individuals (up to $3,850 if they're covered by a self-only health insurance plan or $7,750 if they have family coverage for 2023, or $4,150 for self-only and $8,300 for family coverage in 2024, plus an additional $1,000 catch-up contribution for eligible individuals age 55+);

- Assets in the HSA can be invested, and any growth and/or income earned on the funds is tax-deferred; and

- Withdrawals from the HSA at any point are tax-free if they are used to pay or reimburse the account owner for eligible medical expenses.

The upshot of HSAs' so-called "triple-tax benefit" for people saving for retirement is that an individual can make a tax-deductible contribution in one year, invest the assets in the account to grow potentially over many years, and, as a result, have a bucket of savings that can be withdrawn tax-free to spend on medical expenses in retirement. When used in this way, HSAs can have both a practical and a psychological benefit for retirees: practically, they can effectively boost retirement savings by providing a more tax-efficient way to pay for medical expenses than other types of accounts like IRAs and taxable accounts; and psychologically, they can satisfy the common itch for mental accounting by literally segregating the funds meant for health care costs away from other retirement savings, reassuring retirees that dedicated savings are actually 'there' to cover their medical costs.

Given that medical expenses tend to creep up as a person gets older, it makes sense that a person would want to contribute as much to their HSA as possible as they near retirement. Which might be because they have gotten a late start on building up their HSA funds and want to pack as much in as possible while they still can, or they simply want to take advantage of the HSA's tax-advantaged savings to the fullest extent allowed.

However, unlike other types of savings accounts like IRAs (to which anyone can contribute as long as they have earned income), HSAs have relatively narrow eligibility criteria that individuals must meet to be able to contribute. Specifically, a person needs to be covered by an eligible High-Deductible Health Plan (HDHP) with a minimum deductible of $1,500 for self-only coverage or $3,000 for family coverage, and a maximum out-of-pocket limit of $7,500 for self-only coverage and $15,000 for family coverage for 2023. An individual can be enrolled in their own health insurance plan (such as through their employer or a Federal or state healthcare exchange) or covered by someone else's plan (e.g., covered by their spouse's employer-provided health insurance or, for non-dependent children age 26 or younger, a parent's health insurance plan), but no matter who 'owns' the insurance, the policy needs to meet the HDHP criteria to allow those it covers to be eligible for HSA contributions.

Along with being covered by an eligible HDHP, however, the additional caveat for HSA eligibility is that a person must also not be covered by any other non-HDHP coverage to be able to contribute to an HSA. In other words, if a person is covered by multiple health insurance policies, they'll be ineligible to make HSA contributions if any one of those policies includes non-HDHP coverage.

Delaying Medicare Coverage Allows Working Individuals To Keep Contributing To An HSA

The caveat that a person must be enrolled in an HDHP and not enrolled in any non-HDHP coverage comes up most often in regard to government-funded healthcare programs such as Medicare and Medicaid. Because these programs are not considered eligible HDHPs for HSA contribution purposes, being enrolled in either of them will automatically disallow a person from making HSA contributions, even if they're also enrolled in an HDHP that would otherwise be HSA-eligible.

Most people in the U.S. enroll in Medicare when they turn age 65, which means that, in effect, most people can't contribute to an HSA after their 65th birthday. For people who are either retired, self-employed, or whose employers don't offer health insurance beyond age 65, and who can't be covered under a spouse's employer-provided plan, Medicare really is the only option for health insurance after age 65, meaning that for those groups, turning 65 effectively drops the curtain on eligibility for HSA contributions.

But there is one group of people who can delay Medicare enrollment (and thus stay eligible to make HSA contributions): those who choose to keep working past age 65 (or whose spouses keep working) and who opt to stay on their employer-provided group health insurance coverage. In this case, it's possible for someone to continue making HSA contributions, provided that the following conditions apply:

- They remain on their employer's group health insurance coverage;

- That coverage is an eligible HDHP; and

- They don't enroll in Medicare.

Provided that all of these conditions are met, it's possible for an individual to keep making HSA contributions for as long as they or their spouse continue to work and remain on their employer's group coverage.

How Applying For Social Security Benefits Ends Eligibility For HSA Contributions

If someone working past age 65 wants to continue contributing to an HSA, then delaying Medicare enrollment is the key. Which seems easy enough: All that's needed to delay Medicare enrollment is to simply not enroll in Medicare, right? Except there's one other important consideration for making HSA contributions after 65, which is that along with not signing up for Medicare, an individual needs to also avoid applying for Social Security benefits, since doing so will automatically enroll them in Medicare and, therefore, end their eligibility to make HSA contributions.

It's worth taking a moment to explain how this works in more detail. Broadly speaking, Medicare has 2 parts, Part A and Part B. Part A covers hospital and skilled nursing facility care and usually doesn't require a monthly premium payment by the enrollee, while Part B covers other necessary medical services like doctor visits, screenings, and treatments and does come with a monthly premium. (There are other types of Medicare coverage, like Part D prescription drug insurance and Part C Medicare Advantage plans, but Part A and Part B are the non-optional plans that everybody gets and are what we'll focus on here).

People are eligible to enroll in both Part A and Part B of Medicare at age 65, and there are generally 2 ways to sign up. The first is to apply via the Social Security website or in a Social Security office. For someone who wants to sign up for Medicare in this way for benefits starting at age 65, they can do so anytime during the initial enrollment period (starting 4 months before turning 65 and ending 3 months after). If they're still working and enrolled in an employer's (or in their spouse's employer's) group health insurance plan, they can wait until after their employment and/or group coverage ends to apply, which they can do during a Special Enrollment Period up until 8 months after the last date of their employment or the end of their group coverage (whichever is earlier).

The second way to enroll in Medicare, however, is to sign up for Social Security benefits. If a person is receiving Social Security at least 4 months before their 65th birthday, they'll automatically be enrolled in Medicare starting the month they turn age 65. If they apply for Social Security sometime after age 65 (and haven't already enrolled in Medicare via the first method described above), then they'll be automatically enrolled in Medicare starting the month after they apply for Social Security benefits.

What's notable about receiving Social Security benefits after age 65 is that there is no way to delay Medicare enrollment when doing so. Even if a person is working and enrolled in their employer's group health coverage, they'll still be enrolled in Medicare if they're age 65 or older and receiving Social Security benefits. And while it can be possible to delay or drop Medicare Part B coverage after enrolling, there generally isn't any way to 'turn off' Part A once it's started (other than withdrawing one's application for Social Security benefits entirely, about which more is discussed later on).

For someone who wants to keep contributing to an HSA after age 65, then, the ability to do so depends on not signing up for Medicare or Social Security. Signing up for Social Security after turning 65 triggers Medicare enrollment automatically, which is considered disqualifying non-HDHP coverage for the purposes of eligibility for HSA contributions.

Of course, people who are still working at age 65 and older are presumably still earning income and less likely to need the additional income of Social Security, so it's reasonable to think that many of those workers would opt to delay applying for Social Security anyway. Especially since people often stand to benefit from waiting until at least their full retirement age (67 for workers born in 1960 and later) to receive their full Social Security benefits, or to delay claiming up to age 70 to receive even higher benefits.

However, as more workers extend their working years past age 65 to age 67, 70, and beyond, they may be tempted to believe that there's nothing to lose in claiming Social Security to receive the supplemental income on top of whatever the individual is earning from working. But if they are also contributing to an HSA, then enrolling in Social Security (and thus also enrolling in Medicare) will cause them to cease being eligible for HSA contributions. And if they end up contributing more than they're allowed to as a result, then they'll be forced to withdraw the excess contribution (and any growth attributable to it) or else face a 6% excise tax per year on the excess contribution until it is eventually withdrawn.

Ways To Preserve HSA Eligibility (And Maximize Contributions) Beyond Age 65

Because of the way that the rules for Medicare enrollment, Social Security, and HSA eligibility collide with one another, there's really only one path to remaining eligible for HSA contributions starting at age 65:

- Being enrolled in an employer-sponsored High-Deductible Health Plan (HDHP), either through one's own or one's spouse's employer. Notably, self-employed people or those who otherwise buy health insurance using Federal or state health care exchanges are required to switch to Medicare at age 65, so this only applies to people working as employees (or to the spouses of employees) of a company that offers employer-sponsored qualifying HDHP insurance;

- Not applying for Medicare at age 65; and

- Not claiming Social Security benefits.

Given these criteria, exploring the nuances of HSAs and Medicare can uncover strategies for advisors to help their clients over age 65 maximize their HSA contributions. There are 3 specific strategies worth discussing in detail: Withdrawing an existing application for Social Security to restore HSA eligibility for someone for whom Social Security benefits have already begun; coordinating HDHP and Medicare coverage between spouses to ensure at least one spouse can continue making HSA contributions; and navigating the rules around starting Medicare after age 65 to ensure a smooth transition onto Medicare when an individual does opt to retire.

Withdrawing Social Security Benefits Application To Preserve HSA Eligibility

Let's say that a person applies for Social Security benefits without realizing that doing so will end their eligibility for making HSA contributions, leading them to regret their choice. If it's been less than 12 months since they first applied for benefits, they may be able to withdraw the application, disenroll from Medicare, and restore their HSA eligibility. However, this strategy has some significant tradeoffs, which make it only really worth considering in certain specific circumstances.

The way the withdrawal of benefits application works is that individuals can fill out and submit Form SSA-521 to withdraw their application for Social Security benefits at any time within 12 months of the application's initial approval. While this strategy is most often used for the purpose of delaying Social Security benefits until a later age to receive a higher monthly benefit, the form also includes the option to unenroll in Medicare, which would restore a person's eligibility to make HSA contributions as long as they were otherwise able to do so by being covered by an eligible HDHP.

The main caveat, however, is that withdrawing one's application for Social Security benefits also requires paying back any benefits actually received, which, over a full 12-month period, could amount to tens of thousands of dollars – some or all of which the payee may not actually have on hand to pay back. The Social Security Administration also requires individuals to pay back any funds that were withheld from Social Security payments for income taxes and Medicare Part B premiums, as well as any Medicare Part A benefits paid – meaning that the amount a person would need to repay in order to withdraw their Social Security application could significantly exceed what they actually received in benefits.

Additionally, withdrawing a Social Security application also doesn't retroactively qualify someone to make HSA contributions for the period during which they were receiving benefits – they'll be eligible to contribute starting the month after Medicare coverage is withdrawn, but they won't be able to contribute for any period during which they were covered by Medicare.

In light of the hurdles presented by the process of withdrawing a Social Security application, doing so usually makes sense only when one plans to continue stashing significant amounts into an HSA for at least several more years. Still, if a time arises when a client says, "Oops, I applied for Social Security and now I can't contribute to my HSA anymore", it can be helpful for advisors to know about the application withdrawal process to consider as an emergency 'undo' button that can enable them to continue their HSA contributions.

Maintaining Family HDHP Coverage With Medicare-Eligible Spouses To Maximize HSA Contributions

Although the rule that enrolling in Medicaid will render someone ineligible to make HSA contributions is pretty cut-and-dried for single people, there is notably some leeway around Medicare and HSA eligibility when it comes to married couples. Specifically, if a person working past age 65 is covered by an eligible HDHP and isn't enrolled in Medicare, their spouse can be enrolled in Medicare and/or receive Social Security benefits without affecting the working spouse's eligibility to make HSA contributions.

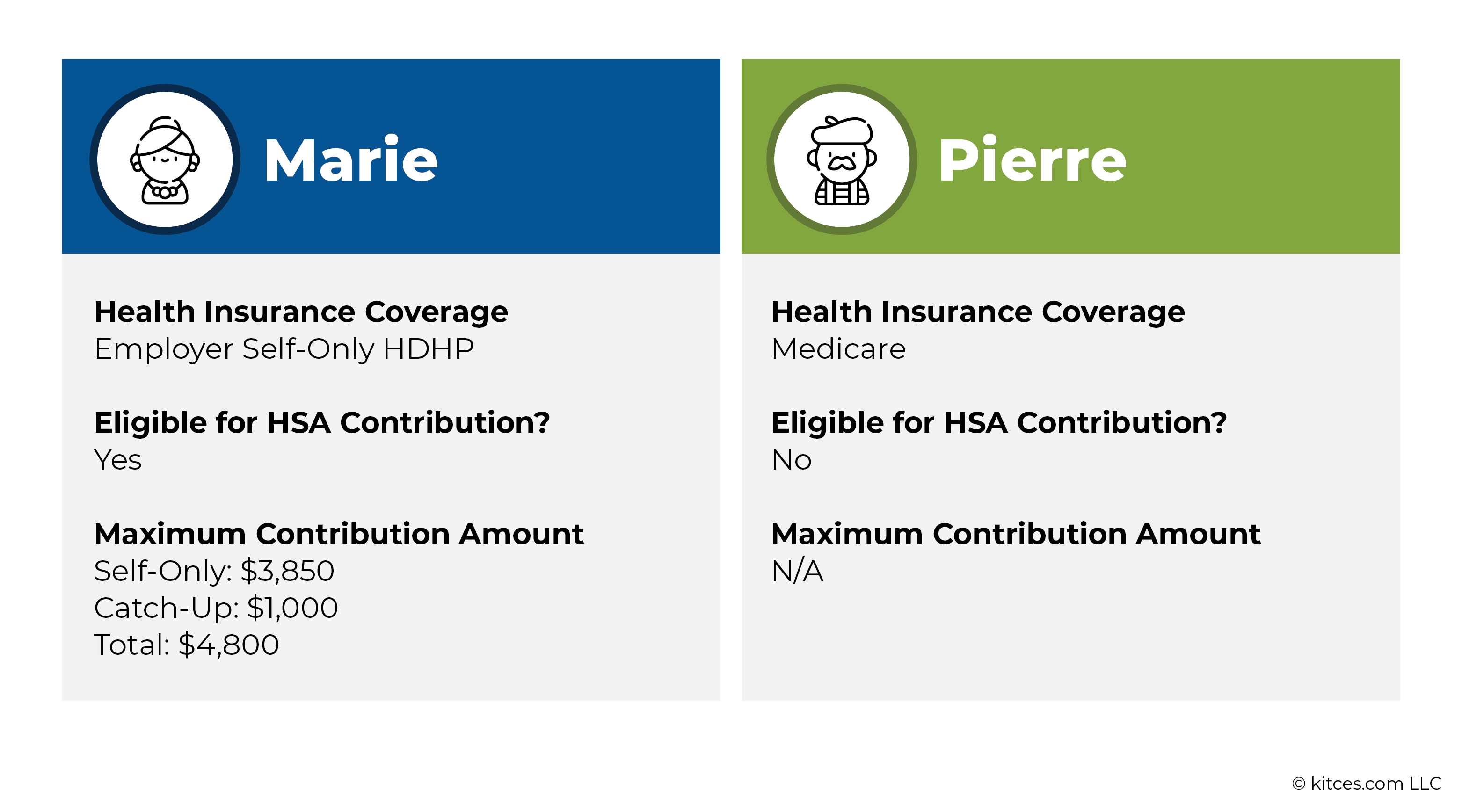

Example: Marie is 65 years old and working and is enrolled in her employer's HSA-eligible High-Deductible Health Plan that covers only her. Marie's spouse, Pierre, who is retired, turned 65 last year and enrolled in Medicare.

Even though Pierre is enrolled in Medicare, it doesn't affect Marie's eligibility to contribute to her HSA. Because she is enrolled in a self-only plan, she can contribute up to $3,850 to her HSA in 2023, plus an additional $1,000 catch-up contribution since she is age 55 or older.

In the example above, each spouse was covered individually by their own separate coverage – Marie by her employer's self-only HDHP and Pierre by Medicare. However, even if Marie's HDHP had covered both her and Pierre, she would have still been able to contribute to her own HSA, even if Pierre was also covered by Medicare.

That's because when both spouses are covered by the same family HDHP (i.e., health insurance that covers both the enrollee and their spouse and/or dependents), one of the spouses can enroll in Medicare and/or file for Social Security benefits without affecting the other spouse's eligibility to contribute to an HSA. Even though the Medicare-enrolled spouse won't be able to make an HSA contribution of their own, the other spouse can remain eligible to make HSA contributions as long as they maintain their HDHP coverage and aren't also enrolled in Medicare.

The upshot to both spouses having family HDHP coverage, despite one spouse also being covered by Medicare, is that it allows the non-Medicare-covered spouse to contribute up to the maximum family contribution to their HSA, rather than being limited to the self-only maximum. Which would allow that spouse to contribute up to $7,750 to their HSA in 2023, as compared to $3,850 using self-only coverage.

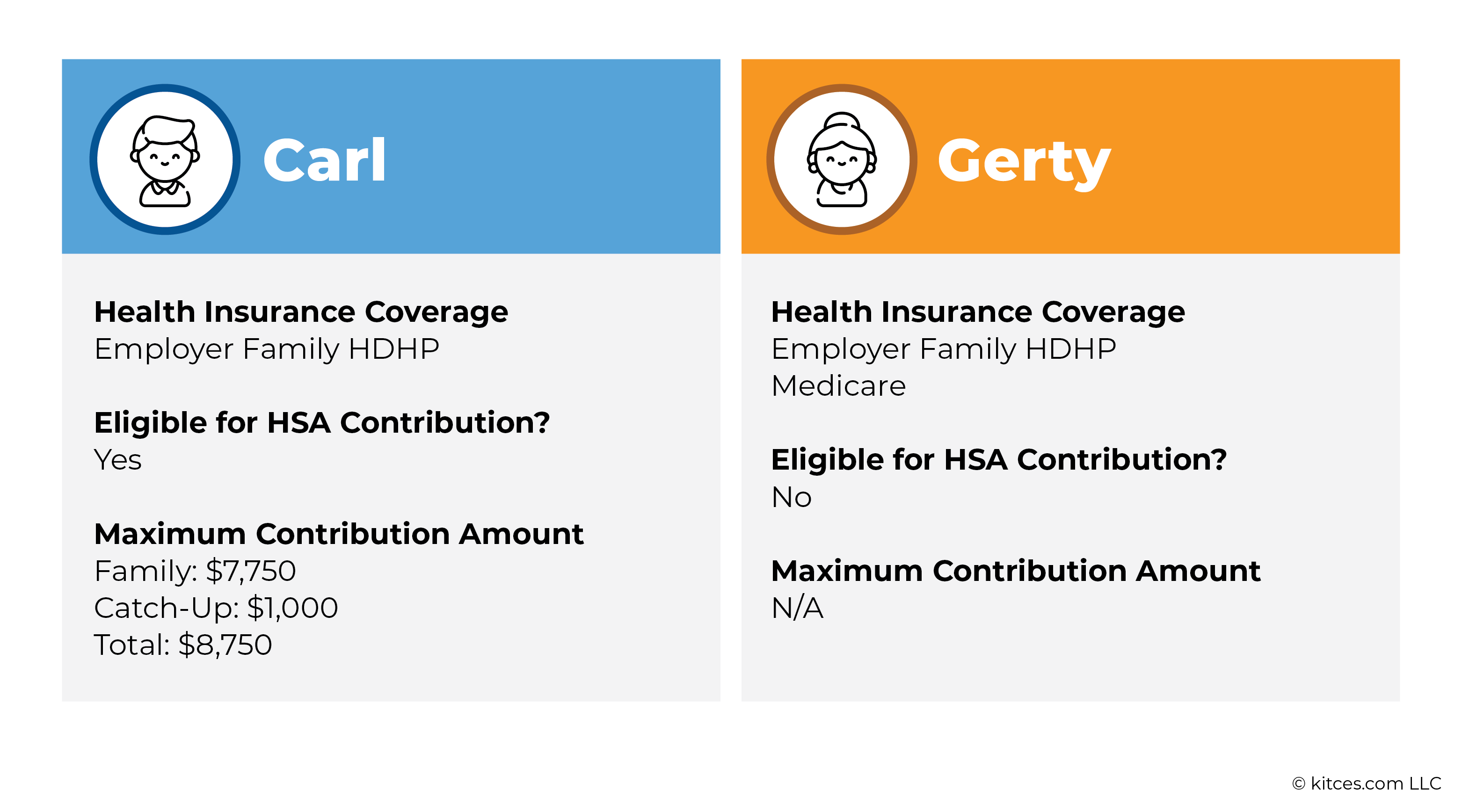

Example: Carl is 67 years old and enrolled in an employer-provided family HDHP. The plan covers Carl and his wife, Gerty.

Gerty turned 65 last year and enrolled in Medicare, so she is ineligible to make any HSA contributions. However, Carl's eligibility to make HSA contributions isn't affected by Gerty's Medicare coverage, and because the HDHP includes family coverage, Carl can contribute up to the full family contribution limit of $7,750 to his HSA in 2023, plus his $1,000 additional catch-up contribution.

Notably, there can be no catch-up contribution for Gerty since catch-up contributions must be made by the actual spouse who is eligible for them – and since Gerty can't contribute to an HSA on her own, she therefore can't make a catch-up contribution for herself either.

These rules were made clear by the IRS in Notice 2008-59, which presents guidance on a number of HSA-related topics in Q&A format:

Q-16. How do the maximum annual HSA contribution limits apply to an eligible individual with family HDHP coverage for the entire year if the family HDHP covers spouses or dependent children who also have coverage by a non-HDHP, Medicare, or Medicaid?

A-16. The eligible individual may contribute the § 223(b)(2)(B) statutory maximum for family coverage. Other coverage of dependent children or spouses does not affect the individual's contribution limit, except that if the spouse is not an otherwise eligible individual, no part of the HSA contribution can be allocated to the spouse.

[Emphasis added]

If one spouse of a married couple is working and the other is receiving Social Security and/or enrolled in Medicare, enrolling in a family HDHP can be worth considering to maximize the potential amounts that the working spouse can contribute to their own HSA. Alternatively, the working spouse could themselves be enrolled in Medicare, but if the non-working spouse were not also enrolled, then they would be able to make the maximum contribution to their own HSA.

Either way, other considerations would factor into the decision, such as the cost of family versus self-only coverage and how Medicare and the employer's group insurance would coordinate benefits. The key point is that the value of the additional HSA contribution, plus the tax-free growth on the funds if they are invested within the HSA, could make those costs well worth it.

Smoothly Navigating The 6-Month Rule For HSA Eligibility Before Medicare

As shown above, a person can generally maintain their eligibility to contribute to an HSA after age 65 as long as they are employed, enrolled in an HSA-eligible HDHP, and not enrolled in Medicare or other non-HDHP insurance. And as long as they continue to meet those criteria, they can keep making HSA contributions year after year, regardless of their age.

But there will almost always come a time sooner or later when retirement becomes inevitable, at which point it's time to transition away from employer-sponsored health insurance and onto Medicare. Unfortunately, however, there are special rules around enrolling in Medicare after age 65 that can make the sendoff less than pleasant for people contributing to HSAs, requiring careful planning and timing to avoid tax complications.

Generally, when a person over age 65 leaves their job and becomes ineligible for employer-provided health insurance, they have an 8-month window known as the "Special Enrollment Period" in which to sign up for Medicare. If they miss that window, they'll need to wait until the next open enrollment period (from January 1-March 31 each year) to sign up and potentially be stuck with a higher lifetime Medicare Part B premium. To avoid these penalties (as well as to avoid risking a gap in coverage between when the employer's insurance ends and Medicare coverage begins), many individuals commonly sign up for Medicare immediately upon retirement.

The caveat for those working and contributing to an HSA after age 65, however, is what's known as the "6-Month Rule", which applies whenever a person signs up for Medicare Part A after turning 65. In these cases, an individual's Medicare Part A coverage begins the later of 1) the month they turn 65 or 2) 6 months before the date that they apply for Medicare.

Nerd Note:

Somewhat confusingly, Medicare Part B coverage usually doesn't start until the month after applying for coverage, resulting in effectively 2 different coverage starting dates: One (Part A) starting 6 months before applying for coverage, and one (Part B) starting the month after applying (or, if applying no later than the first month of the Special Enrollment Period, on the first day of any of the following 3 months). But because HSA eligibility is lost when someone is covered by either Part A or Part B, the earlier Part A coverage date is usually what matters regardless of when Part B eligibility begins.

For someone working beyond age 65 who plans to switch to Medicare upon retirement, then, their Medicare Part A coverage would actually start 6 months before their retirement date – and because Medicare Part A is considered non-HDHP coverage for HSA purposes, their eligibility to contribute to an HSA would also end 6 months before retirement.

Example: Rosalind is 67 years old and plans to retire on August 1. On July 1, she applies for Medicare so her benefits can start on her retirement date.

Because Rosalind applied for Medicare on July 1, her Medicare Part A coverage is considered to have begun 6 months earlier, on January 1. Which means that her eligibility to make HSA contributions ended on the previous day, December 31.

In other words, she isn't eligible to make any contributions for this year, and any contributions she did make would be considered 'excess contributions' that would need to be withdrawn from the HSA before the current year's tax filing deadline, or else she would owe a 6% annual excise tax on those amounts.

A common myth about the 6-month rule is that an individual can't make any HSA contributions within 6 months of applying for Medicare benefits. However, as Notice 2008-59 states:

An individual who ceases to be an eligible individual [e.g., upon being covered by Medicare] may, until the date for filing the return (without extensions) for the year, make HSA contributions with respect to the months of the year when the individual was an eligible individual.

In other words, an individual who is eligible for HSA contributions for only part of the year is limited to a pro-rated contribution amount based on the number of months in which they were eligible – however, they can still actually contribute that amount up until that year's tax filing deadline (i.e., April 15 of the following year), no matter when they actually start their Medicare coverage.

The formula that can be used to calculate the maximum HSA contribution in a year of partial eligibility is (the maximum annual contribution) × (the number of months in which the individual was eligible to contribute on the first day of the month) ÷ 12.

Example: Katalin plans to retire on her 70th birthday on December 5, 2023. On November 15, she applies for Medicare benefits to start December 1.

Because of the 6-month rule, Katalin's Medicare Part A benefits are considered to begin 6 months before she applied for benefits, or May 15, 2023, meaning she is ineligible for HSA contributions after that date. Although she was ineligible for part of May, she was eligible on the 1st of the month, meaning that there were 5 months (January, February, March, April, and May) in which she was eligible for HSA contributions.

Assuming she is enrolled in self-only HDHP coverage, Katalin's maximum contribution for the year is $3,850 (the maximum self-only contribution) × 5 (the number of months in which she was eligible) ÷ 12 = $1,604. If she hasn't already contributed this amount, she can do so up until April 15, 2024.

When a person applies for Medicare benefits within the first 6 months of the year, the 6-month rule can also impact HSA eligibility for multiple tax years:

Example: Trudy is 68 years old and plans to retire on April 1, 2024. She applies for Medicare benefits on March 15 to begin on her retirement date.

Because of the 6-month rule, Trudy's Medicare Part A coverage is considered to start 6 months before she applied for benefits, or September 15, 2023. This means that she was eligible to make HSA contributions for the first 9 months of 2023 (including September, because she was eligible on the 1st day of the month), but she was ineligible for the final 3 months of 2023 and for all of 2024.

Assuming Trudy is enrolled in self-only coverage, her maximum contribution for 2023 is $3,850 (the maximum self-only contribution) × 9 (the number of months in which she was eligible) ÷ 12 = $2,888.

Because she's covered by Medicare and therefore not eligible for HSA contributions for any months in 2024, she can't make any contribution for 2024.

Unfortunately, Trudy didn't know about the 6-month rule and had already contributed $3,850 to her HSA for 2023. This results in an excess contribution of $3,850 – 2,888 = $962, which must be withdrawn from the HSA by the tax filing deadline of April 15, 2024, to avoid a 6% excise tax on the excess amount.

While a soon-to-be retiree doesn't necessarily need to stop making HSA contributions 6 months before retirement, they should still plan in advance to determine their maximum HSA contribution and ensure that they don't exceed this limit.

As noted earlier, when a person delays Medicare while working after age 65, upon leaving their job, they have an 8-month window following the earlier of the date that their group health coverage ends or the date their employment ends to sign up for Medicare during the Special Enrollment Period. If someone misses that enrollment window following their retirement, they'll need to wait until the next Medicare General Enrollment Period (lasting from January through March each year) and, if the gap between group coverage and Medicare lasts more than 12 months, they'll pay an extra 10% penalty on their Medicare Part B premiums for the rest of their life.

The key point is that while it's possible to continue contributing to an HSA after age 65, doing so introduces an extra layer of planning to stay within all of the applicable rules and maximize the HSA's benefits. To maintain eligibility, individuals need to wait to sign up for Medicare and delay filing for Social Security benefits until they decide to either stop working or stop contributing to the HSA.

Spouses can coordinate their coverage so that one spouse will be able to use their own Medicare and Social Security benefits without affecting the other spouse's eligibility, and enrolling in family coverage (even when one spouse is enrolled in Medicare) allows the spouse who has the HSA to make the highest possible contribution.

When it is time to retire, planning for the end of HSA eligibility while factoring in the 6-month rule for Medicare Part A coverage can help avoid an inadvertent excess HSA contribution (and the headaches that come with withdrawing excess contributions and potential penalty taxes).

But for all of the planning hurdles created when contributing to an HSA after age 65, the benefit of a sizeable bucket of savings that can be used tax-free to pay for medical expenses in retirement can be more than worth it. And given that these tools will almost always be used for someone who is already planning to continue working after age 65, there's little reason not to take advantage of the most tax-efficient savings vehicle for as long as possible!

Leave a Reply