Executive Summary

Financial advisors are often responsible for working with a wide range of individuals, both among their client base and coworkers, who each have their own personality, beliefs, and style of communication. While it can be rewarding to build a large breadth of relationships, it can also be challenging to appeal to and feel accepted by so many different people all at once. One way that some advisors cope with this challenge is to 'cover' – that is, to downplay or conceal aspects of their own personality or values in order to fit in.

Research has shown that covering is a common phenomenon in the general population, and the most recent Kitces Research study on wellbeing has shown that it is also common among financial advisors: Approximately 40% of advisors responded that they hide aspects of their personal lives from both their coworkers and clients. Importantly, advisors who strongly agreed that they cover in the workplace also reported lower quality-of-life scores, presumably because spending so much time in an environment where they feel they cannot express their true selves would understandably cause a decline in wellbeing.

While covering is a universal phenomenon, Kitces Research suggests it is more prevalent among advisors at larger firms (defined as those with seven or more members) than those at smaller firms. While it makes intuitive sense that advisors at a larger firm might feel more pressure to downplay personal traits among their coworkers, what is notable is that advisors at larger firms are also more likely to do so with their clients. Which suggests that covering might not just be an issue of an advisor's personal insecurity, but may also be rooted in the culture of larger firms. And this may encourage advisors to suppress their unique personalities and fit in with the crowd.

In addition to firm size, several other factors are also associated with covering. Advisors whose personality traits do not align with stereotypical gender roles – e.g., confidence and assertiveness in males; gentleness and deference in females – may feel pressured to conform to what they think is expected of them. Likewise, advisors with more junior roles and less experience also feel less confident in expressing themselves than their more senior colleagues.

Ultimately, most everyone feels pressure to cover at some point, but when that pressure is present in one's work environment every day, it can have a detrimental impact on wellbeing. It's important for advisors to find ways to authentically express themselves – whether by building deeper relationships with work colleagues or clients, or seeking out mentors or study groups – and also for firms to provide a culture where employees feel comfortable doing so. Allowing advisors to openly share what makes them unique can help create a more diverse, inclusive, and happier financial planning industry!

When Financial Advisors 'Cover', It Impacts Wellbeing

Covering, as defined by its originator, legal scholar Kenji Yoshino, is when someone hides or downplays personal aspects of themselves to fit in. Multiple research studies have shown that, for many professionals, covering is a very common practice. For instance, Yoshino reports in his 2007 book, Covering: The Hidden Assault On Our Civil Rights, that nearly 61% of the population has concerns about openly expressing their authentic selves in the workplace and that different groups cover more or less often than others. Yoshino's work reported that 83% of LGBT+ individuals cover, and 45% of straight, white males also cover.

Covering, as defined by its originator, legal scholar Kenji Yoshino, is when someone hides or downplays personal aspects of themselves to fit in. Multiple research studies have shown that, for many professionals, covering is a very common practice. For instance, Yoshino reports in his 2007 book, Covering: The Hidden Assault On Our Civil Rights, that nearly 61% of the population has concerns about openly expressing their authentic selves in the workplace and that different groups cover more or less often than others. Yoshino's work reported that 83% of LGBT+ individuals cover, and 45% of straight, white males also cover.

Essentially, covering happens a lot. According to Yoshino, it generally arises from a fear of drawing unwanted attention or making others feel uncomfortable. For instance, in an industry such as financial planning, where a large portion of advisors appear to be mentally healthy, those who struggle with mental illness may feel pressure to appear more like the healthy archetype. To further examine such factors as these, the most recent Kitces Research study on advisor wellbeing explored the phenomenon of covering in the financial planning industry: who is doing it, where it happens, and what impact it has on an advisor's life.

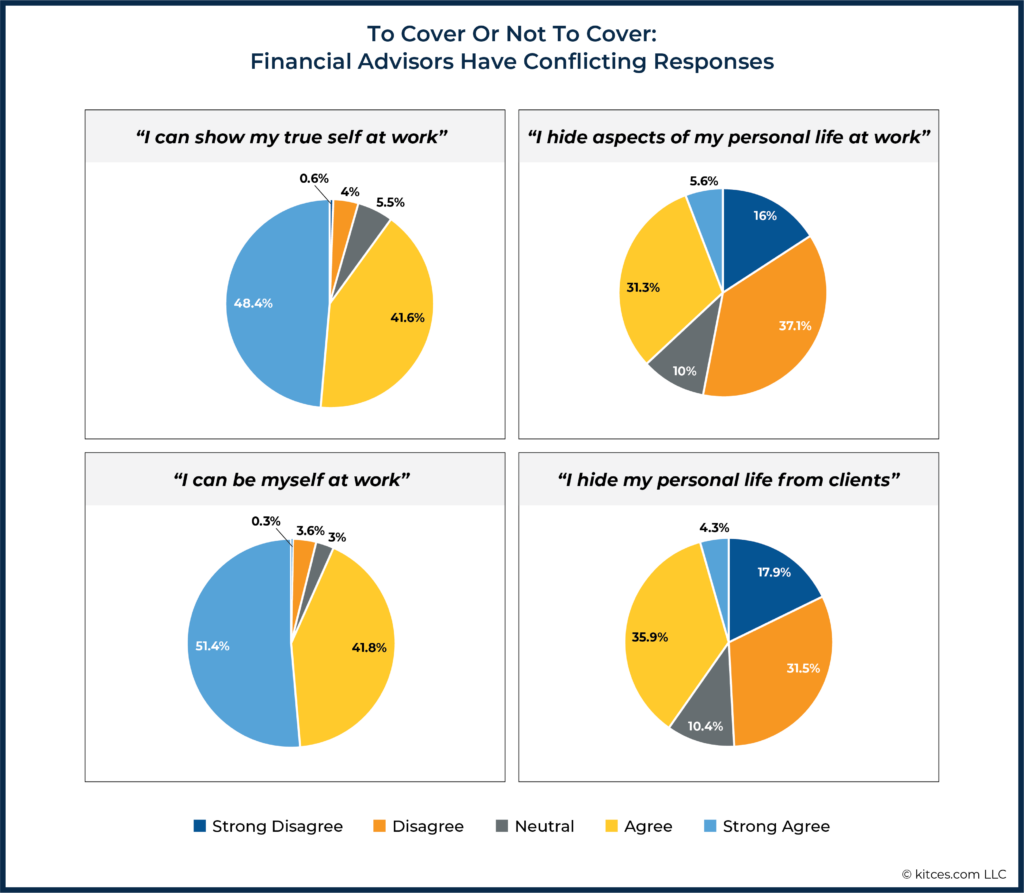

But identifying who feels the need to cover (and how often it actually happens) is not so simple. While the Kitces Research study found that out of approximately 1,600 advisors, most agreed or strongly agreed with the statements "I can show my true self at work" (89.9%) and "I can be myself at work" (93.1%), when prompted with contrasting statements, the numbers seem to tell a different story. In fact, 36.9% of advisors agreed or strongly agreed with the statement, "I hide aspects of my personal life at work", and 40.2% agreed or strongly agreed with the statement, "I hide my personal life from clients".

These seemingly contradictory results are actually not so surprising when put into the context of Yoshino's findings about covering. Yoshino suggests that covering is nearly universal. Additionally, while he stresses that covering is different from the issues targeted by diversity, equity, and inclusion initiatives, he also suggests that covering should be discussed alongside diversity, equity, and inclusion because of its nearly universal experience. While a great majority of us feel the need to cover by hiding some aspect of ourselves at some time, only a minority of us always feel we are in the minority – and both discussions are important.

These seemingly contradictory results are actually not so surprising when put into the context of Yoshino's findings about covering. Yoshino suggests that covering is nearly universal. Additionally, while he stresses that covering is different from the issues targeted by diversity, equity, and inclusion initiatives, he also suggests that covering should be discussed alongside diversity, equity, and inclusion because of its nearly universal experience. While a great majority of us feel the need to cover by hiding some aspect of ourselves at some time, only a minority of us always feel we are in the minority – and both discussions are important.

For example, as a 38-year-old white female with one foot in academia and one in the financial planning industry, I am not part of an underrepresented minority, nor do I feel excluded or unfairly compensated. I have had the privilege of working in safe and welcoming environments. Yet, despite the fact that I don't personally struggle with diversity, equity, and inclusion issues in my own workplace, I do still feel inclined to cover from time to time. And that is the point, conversations to address all of these issues – diversity, equity, inclusion, and covering – should not be ignored.

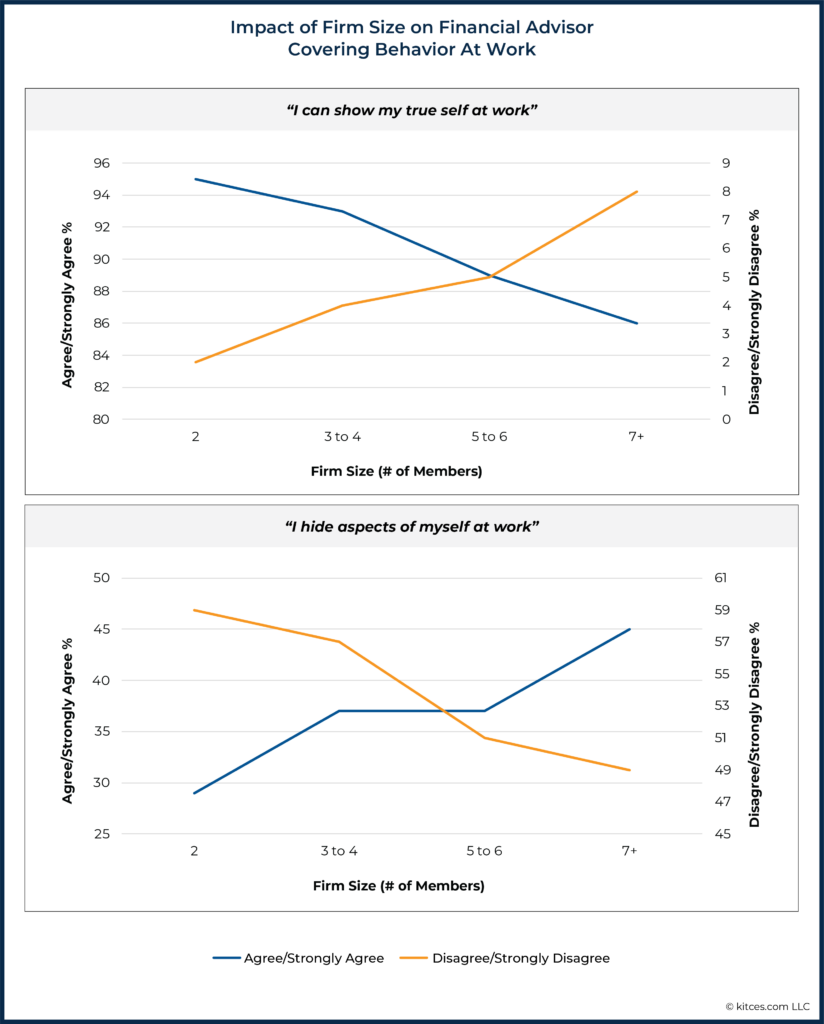

Another interesting result that was revealed in the data related to firm size. In short, as small firms grew larger (i.e., moving from a firm with 2 members compared to one with 7+), a greater percentage of advisors in firms with more members agreed with the statement "I hide aspects of my personal life at work". A related finding indicated that, as firms grew larger, fewer advisors 'strongly agreed' that they could be themselves at work. While the differences between responses were subtle (where most advisors moved from strongly agree to simply agree), the changes remain obvious – firm size does appear to have a negative relationship with how comfortable people feel being themselves.

In its simplest interpretation, these results could be likened to a situation where someone enters a room of 7 people who they know, but may not know very well (like multiple colleagues in a 7+ financial planning firm), and feels insecure about expressing themselves openly. Conversely, if this person were to enter a room of just 2–3 people instead, they might feel much more comfortable expressing themselves in a smaller group.

If we consider these findings in the context of the financial planning industry, larger firms have the opportunity to offer greater diversity (because there are more people) and have made efforts to focus on inclusion (although it remains a struggle for our industry), yet – here it is again in the data – larger firms potentially offering greater diversity are not necessarily leaving advisors feeling comfortable enough to be their authentic selves at work.

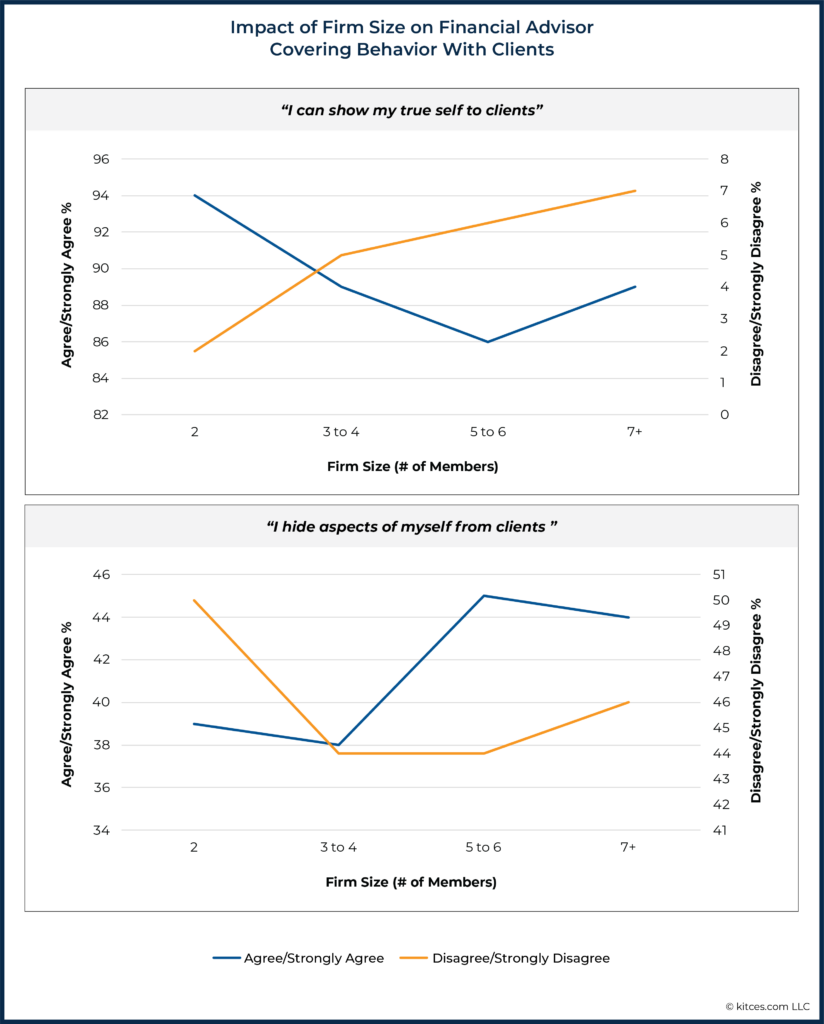

Advisors also reported similar trends for covering when interacting with clients. It isn't clear what would cause these results; one possibility may be that the propensity to cover is related to the 'cover culture' as the firm size grows, where the general discomfort within the firm may spill out onto client relationships.

Another question is, why do people cover in the first place? Covering may happen for a variety of important reasons. For example, some may cover because they feel unsafe expressing their true selves. This may be because of a fear that doing so may lead to others rejecting who they are, resulting in feeling left out of social circles they once belonged to or wish to join.

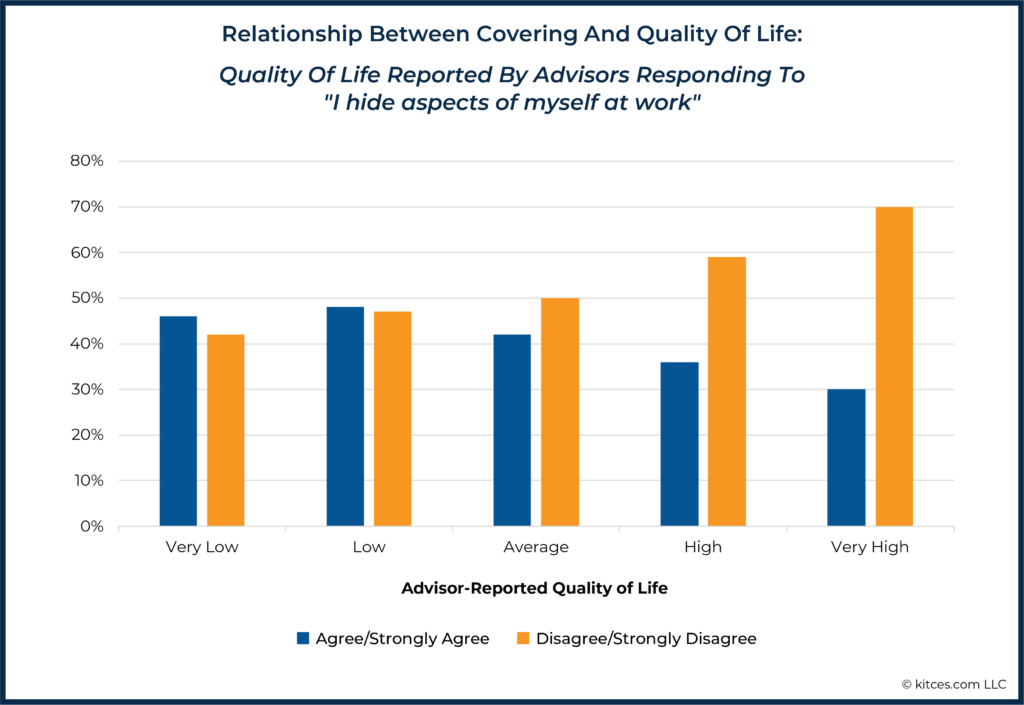

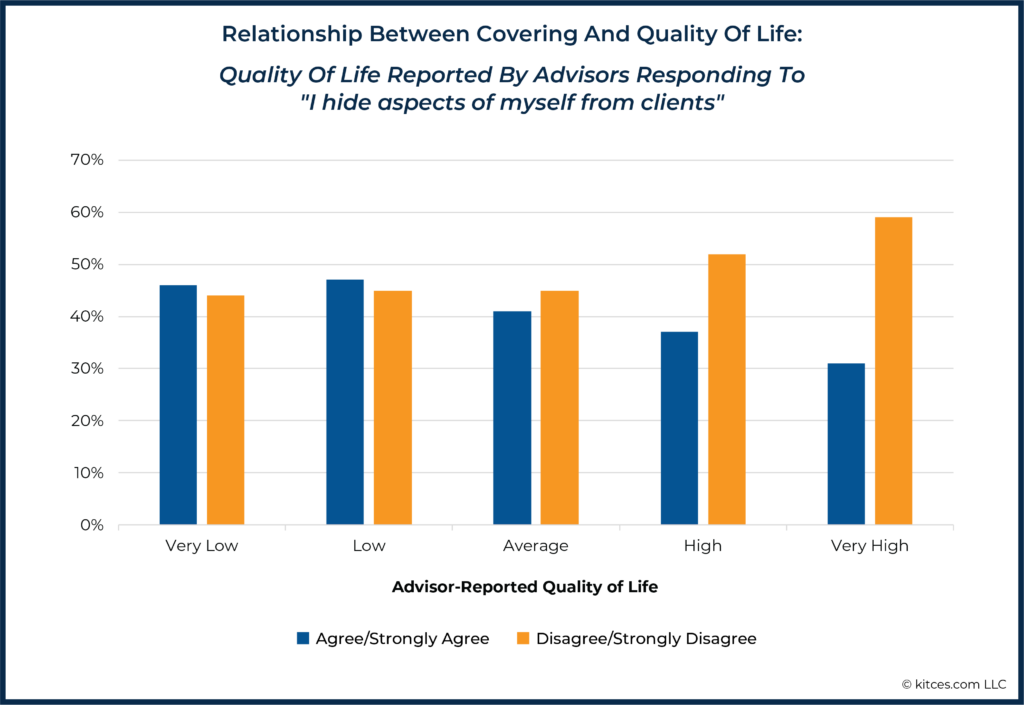

Advisors, like anyone else, want to experience wellbeing at work and want to feel connected to their colleagues. They also want to get along with clients – some advisors specialize in niches just so that they can more fully engage with particular types of clients that they are happiest helping. To this end, the Kitces Research study examined the relationship between advisor wellbeing and covering. Unfortunately, the study found that advisors who agreed that they did hide aspects of their personal lives also reported lower quality-of-life scores, and those who did not agree they covered reported higher scores.

A similar pattern was reported by advisors responding to hiding their personal lives from clients – advisors who agreed that they hid aspects of their personal lives from clients tended to report lower quality-of-life scores.

These data lead us to believe that advisors do feel the need to cover. While the size of an advisor's firm certainly impacts the degree of covering reported, the bigger concern is the impact that covering has on an advisor's wellbeing. Because feeling safe to be ourselves matters.

Gender, Position, And Tenure Are Personal Factors That Relate To Covering

While our research identified that firm size was the one external factor that had the most impact, we also wanted to examine demographic factors about who was more likely to cover. The three aspects of individual identity that helped to reveal who would be most likely to cover involved gender, position, and tenure.

Gender Differences In Covering Behavior

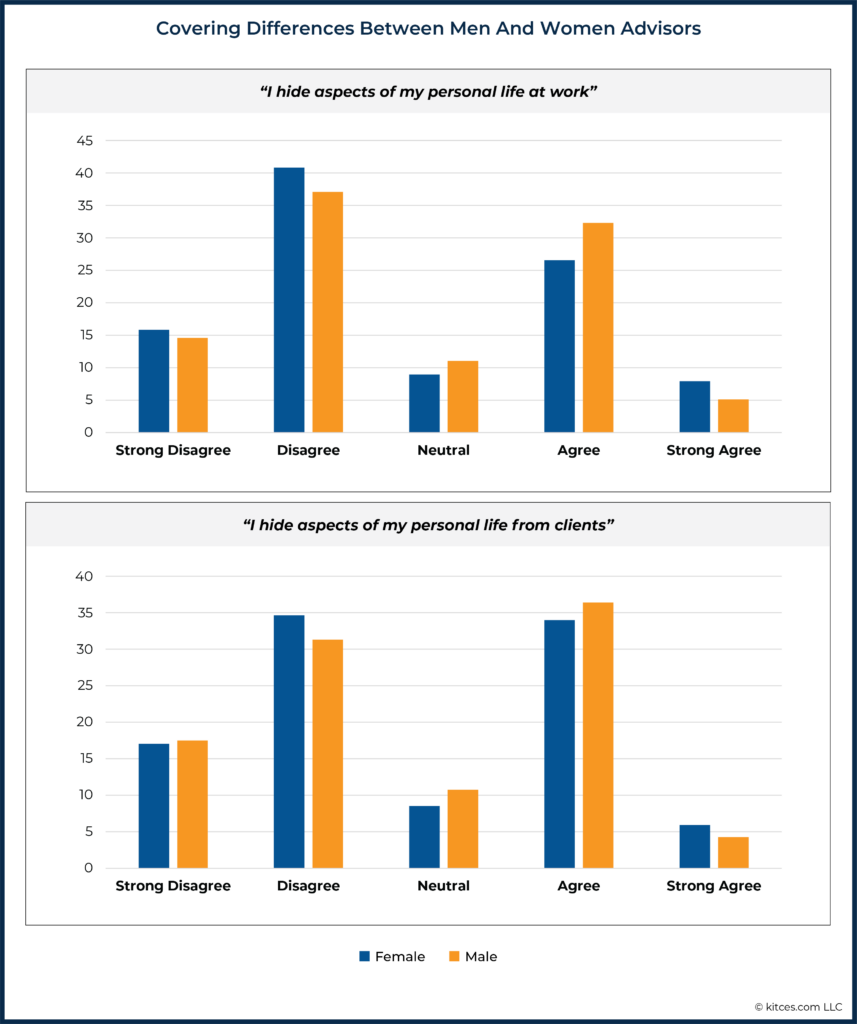

As seen in the data below, when compared to men, more women indicated that they 'strongly agreed' to hiding aspects of their personal life at work and from clients – and although this result may not look dramatic (7.9% of women versus 5.1% of men), it is still an interesting finding. Women are different than men at the extremes.

Interestingly though, there were more men who indicated that they 'agreed' (versus 'strongly agreed') to the same action; when combining both responses ('agreed' and 'strongly agreed'), it turns out that more men than women reported actively hiding an aspect of their personal life with work and/or clients.

These results could be interpreted to mean that while many advisors, regardless of gender, feel the need to hide something at least part of the time (that follows from past covering research), when women do it, they tend to be more aware of their need to do so, possibly as a result of feeling subject to disturbing gender-based double standards.

For example, a male, as mentioned above, might hide his mental health, how he spends his weekend because he feels he has an odd hobby, his sexual orientation, religion, or something else entirely. Yet, at the end of the day, male advisors still 'look' the part of the 'typical' financial advisor archetype – they are male. And they can be expected to display what are considered traditionally 'male' traits like confidence, competitiveness, or assertiveness without the fear or worry that many women often have of being seen as a know-it-all, bossy, or worse.

In my own experience as a woman in this industry, I have been and continue to be keenly aware of such double standards. I have personally attended industry events where I felt very aware of my femaleness and how my behavior would be interpreted in a very different way than if the same behavior were displayed by a male colleague. For example, this may be as simple as who does and does not get interrupted when they are speaking.

Covering has also taken the form of how I speak, where I sometimes end my sentences with a question, asking, "Is that okay?" or "Does that make sense?" as a way to soften my assertiveness when presenting a talk. However, my male colleagues generally do not use the same approach to language when they speak. If I were to conduct myself as assertively as my male counterparts, I fear (whether my fear is based on reality or not) that my assertiveness would be interpreted as rudeness, whereas the same behavior in men would be interpreted as confidence… and therefore I cover.

How Job Position Impacts Covering Behavior

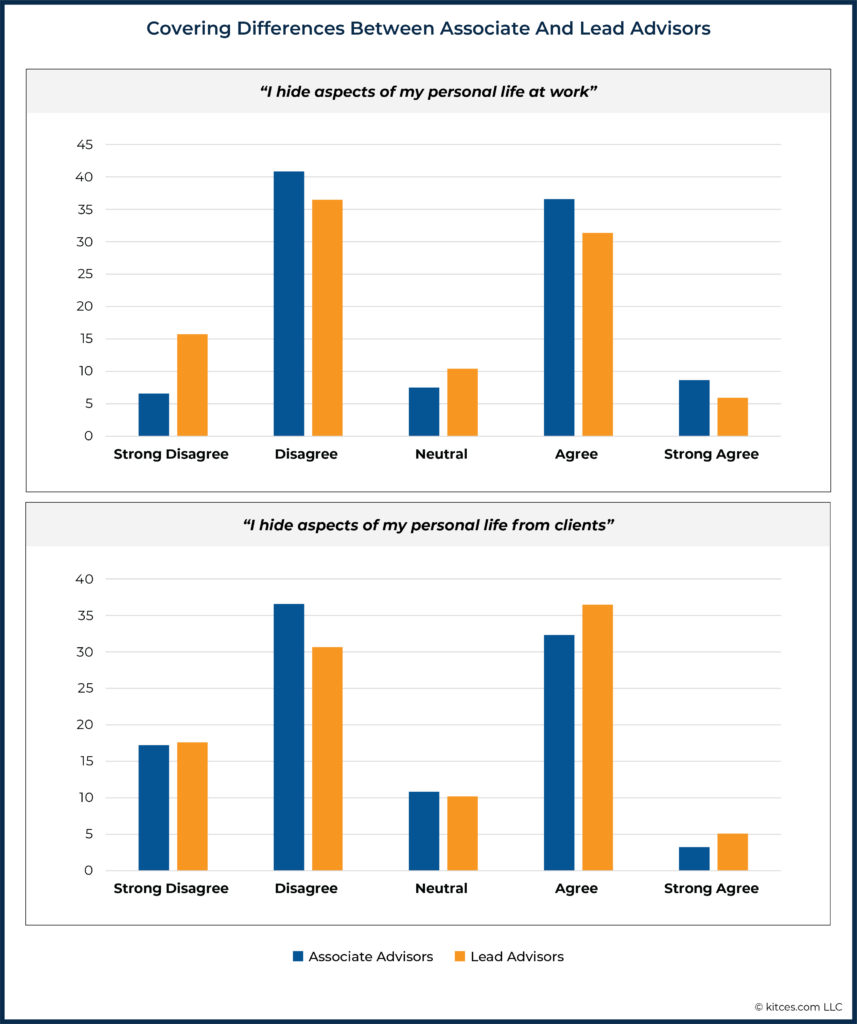

In addition to gender, another factor that impacts covering behavior in financial advisors is their job position within their firm. Advisors with more junior roles, such as associate advisors, appear to be more likely to hide personal aspects of themselves at work, whereas lead advisors appear to be more likely to hide aspects of their personal lives from clients.

This may mean that while less experienced advisors are still finding their way in their firms and often have very little personal contact with clients, their tendency to cover has more to do with concealing their authenticity from coworkers. Yet, lead advisors work much more closely with clients and spend more time with them, so their tendency to cover happens more often in client relationships. Furthermore, lead advisors may be more comfortable with their place in the firm and, therefore, less inclined to feel a need to hide aspects of their personal lives from their colleagues.

Interestingly, in recent conversations I've had with advisors about their relationships with clients, advisors have said that the need to cover from clients comes up more now than in past years. One advisor attributed this change to the charged political polarization and other larger societal divisions that exist in our culture today.

Moreover, the sensitivity to a client's ideals and differences in viewpoints are important areas for future research – how much does it matter if we agree with our clients' political views in order to serve them? While advisors may need to be aware of their clients' belief systems, does that also mean that advisors must agree with them to serve their clients' best interests? Is the tendency to cover when there are clashing beliefs a professional way of saving face? Should all discussions about politics or religion be limited to family gatherings, or might this be an opportunity for more niche firms to serve clients based on political, social, or religious beliefs?

How Many Advisors Find Happiness Despite The Propensity Of Covering Behavior

Newer advisors who are first starting out and navigating how they fit in at their firms can feel overwhelmed, especially at larger firms. And, as time goes on and the number of relationships with clients grows, managing expectations and showing up authentically can also become increasingly challenging. Furthermore, advisors will be faced with different sets of challenges continually at different times throughout their careers. Data from FINRA shows that for 2019 and 2020, more registered representatives left the field than those that entered it!

Despite the challenges advisors face throughout their careers, with different sets of challenges arriving at different times throughout an advisor's career, there are steps that advisors can take to deal with the challenges of covering.

The data from our study does seem to suggest that advisors can cultivate relationships where they can honestly and genuinely express themselves with time. As the saying (and truth!) goes, Monet grew his gardens before he painted them. All masterworks, including every advisor's life's work, take work and take time. We are very likely to get out only what we put into that work. So first of all, hang in there (and build tenure!), and don't give up.

Second, advisors can proactively look for ways to uncover and share their authenticity in situations with low stakes. This could mean finding a mentor outside of the advisor's firm or talking to a trusted supervisor within the firm. Good supervisors and mentors (especially when the issue tends to be more about covering with clients) may offer huge benefits, especially if the supervisor was once in the advisor's shoes (e.g., is the same gender or faced similar challenges while working in the same position as the advisor).

Another idea is to find a study group (or any other group) of advisors with whom the advisor feels they can be themselves. Actively searching for meaningful connections is important – which can consist of building friendships at work or finding clients that are enjoyable to work with and who value the advisor's authentic energy and relationship with them. Again, while it is very common for advisors to hide aspects of themselves, it is just as common for those advisors to want to feel connected to others.

Third, because financial planning is more diverse than ever, advisors may find success in dealing with covering challenges by exploring new roles and different jobs with other firms. The grass really can be greener somewhere else. As mentioned earlier, big firms may promote diversity, but that does not always mean that there is a firm culture of being inclusive and accepting of diversity. Some advisors may very well find that they are happier at a smaller firm, which may enable the advisors to build closer relationships with fellow advisors and other office members. Some smaller firms may have more flexible cultures; furthermore, the beliefs of an employee at a smaller firm will generally have a larger pull.

Lastly, advisors can consider venturing out on their own to start their own firms. Even though this is a big leap, many advisors have been successful at making this leap in many different ways!

Ultimately, the key point is that advisors do not have to stay where they do not feel valued or do not feel they can be themselves. Individuality and diversity matter to our industry, and we can only make it better by openly sharing what makes each of us unique.

While an advisor's role, experience, and gender may influence covering behavior, the precise reasons behind why these factors uniquely affect covering are unknown. We might speculate that newer advisors whose main role is to support lead advisors may simply want to get along with colleagues (so may cover in order to fit certain expected stereotypes), whereas lead advisors who spend more of their time with clients may be more concerned with projecting an image that they think the clients will accept and like (and so they focus their covering on clients).

Being afraid to openly express our authentic selves is common; there is no way around it. And while the tendency to cover might sometimes have no ill effects at all – maybe you're shy about a nerdy hobby, and you don't want to discuss it at work because you don't know your new office that well – extensive or prolonged covering, or covering that happens because we feel judged and undervalued, does not feel good and can have a detrimental impact on our wellbeing.

Given the data we collected, we believe that financial advisor covering is a worthwhile discussion to have. Our proposed interpretations will hopefully push the industry beyond anecdotes toward a broader, more data-based understanding of trends so that we can respond to them most effectively. And despite the pervasiveness of covering, there are things that advisors can do about it. The financial planning industry is changing, and advisors have more and more choices about where, how, and with whom they work. So if you are not happy, make a change and stick around for a little longer – the data suggests that it can be better!

What this article (and the entire woke generation) misses is that diversity and inclusion covers more than just race and sexual orientation. While these factors are critical, so too is diversity of thought (including political beliefs).

Because many of us hold beliefs that are non-negotiable (current headline example being abortion laws), a certain level of covering is required for a healthy work environment. For example, in a “no-covering” workplace, what happens when two coworkers share that one spent the weekend volunteering at an abortion clinic and the other spent the weekend protesting at a clinic? How will the team meeting go after that un-covering?

In all of my teams we have a strict “covering” policy in the form of no-politics and no sharing of things others on the team would find wildly offensive (woke or not).

well said! or how does no-covering go when one advisor says he/she doesn’t think there are gender-based double-standards? Or that DEI hiring practices are anti-meritocratic and discriminatory? A no-covering policy is recipe for internal discord at firms, esp when ppl today tend to make the political personal & then make moral judgements accordingly

As the author of this post I encourage discourse on this topic. It is an important one for our industry and I believe any discussion is good discussion – whether we agree or not -to further DE&I alongside covering.

If you are an advisor reading this post and would like to talk about options related to safe, positive, and professionally open environments please reach out to me and let’s have that discussion. [email protected]