Executive Summary

For high-net-worth individuals who built their wealth through entrepreneurship and creating a business with substantial value, a significant challenge is not only that the business will someday be subject to estate taxes, but that the continued growth and success of the business just compounds the problem further.

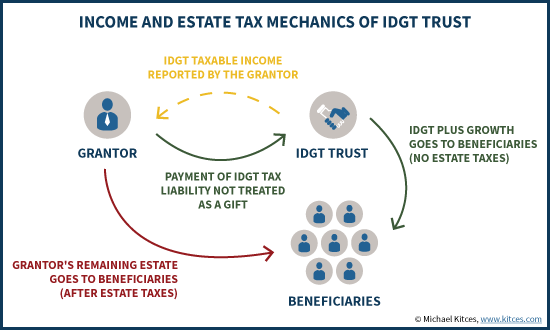

Accordingly, an increasingly popular strategy in recent years to manage this issue is the Intentionally Defective Grantor Trust (IDGT), a unique type of trust structure where the income of the trust is still the grantor’s for income tax purposes, but the assets of the trust are excluded from his/her estate for estate tax purposes. In other words, the trust is “effective” for estate taxes, but “defective” for income taxes.

The benefit of this arrangement is that the value of the trust, and any growth thereon, are excluded from the grantor’s estate. But the fact that the trust is “defective” for income tax purposes is also a good thing, as it means the grantor can pay all of the IDGT’s income tax bills (without being deemed a gift), and can sell the family business to the IDGT in exchange for an interest-only installment note, without triggering capital gains taxes (since the grantor is effectively just selling the business to themselves).

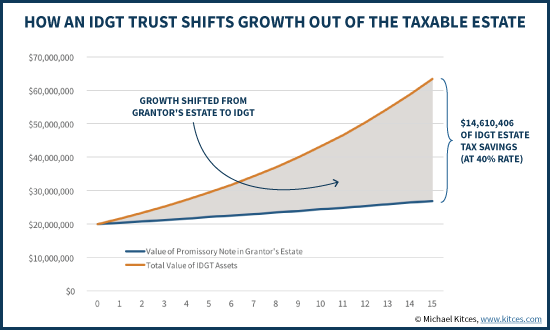

Which means in essence, establishing an IDGT and then selling the grantor’s business to it, in exchange for a promissory note, means the grantor has transmuted his/her assets from a potentially high-return high-growth family business into a low-yield bond (given today’s low Applicable Federal Rates that are used to determine the interest rate for the installment note sale).

And in the long run, this can produce a substantial estate tax savings, to the extent that the business inside the IDGT outgrows the relatively low hurdle rate associated with the installment note. In fact, the strategy can be further leveraged by obtaining valuation discounts on the sale of the family business as well, though notably a recent proposed Treasury Regulation would crack down on such discounts, potentially as early as 2017. Nonetheless, even without a potential valuation discount, the opportunity for estate tax savings in using an IDGT is significant in the long run, simply for the ability of a successful family business to outearn and outgrow today’s ultra-low interest rate environment!

What Is An Intentionally Defective Grantor Trust (IDGT)?

“Intentionally defective grantor trust” (IDGT) describes a type of irrevocable trust where trust income is treated as the grantor’s for income tax purposes, but assets of the trust are not treated as the grantor’s property for estate tax purposes. The strategy is also sometimes known as an Intentionally Defective Irrevocable Trust (IDIT) as well.

The significance of assets held in an IDGT (or IDIT) being treated as “outside” of the grantor’s estate means that the value of the trust, along with any future growth thereon, will not be subject to estate taxes when the grantor passes away. In fact, an IDGT is often designed to be a multi-generational “dynasty” trust, or in states where it is permissible, a perpetuity trust, just to ensure that its assets continue to grow outside of any estate tax exposure for the indefinite future.

On the other hand, the fact that the IDGT’s income is still treated as the grantor’s for income tax purposes means that the annual taxable income of the trust will still be taxable to the grantor, who must report the income on his/her tax return and pay the associated tax liability.

However, in practice this is actually good for tax planning purposes, because the taxes were going to have to be paid by someone no matter what. But paying the tax liability from the grantor’s assets comes from dollars that would have also faced estate taxes, while allowing the IDGT assets to grow outside the grantor’s estate unfettered by income taxation. And the grantor doesn’t even have to report the payment of the IDGT’s tax liabilities as a gift under Revenue Ruling 2004-64 (nor does the paying the trust’s tax liability cause the trust to be included in the grantor’s estate, as long as the trust merely has the option to, but isn’t required to, reimburse for the tax liability).

“Defective” Trust Powers That Trigger Grantor Trust Status But Not Gross Estate Inclusion

The intentionally defective grantor trust is called “defective” because of its unique combination of having its income included as the grantor’s for income tax purposes while trust assets are excluded for estate tax purposes. In most situations, assets that are owned by someone are treated as theirs (including the income thereon), while assets that are not owned by someone are not treated as theirs for estate tax purposes (and the income isn’t theirs, either).

However, when it comes to determining whether assets held in a trust (and the income generated by those assets) will be treated as the grantor’s (or not) are less straightforward, due to the complex ways that some trusts can be structured. Since legally, the trust often is a separate legal entity, it’s necessary to look at the powers and retained rights that the grantor has over the trust’s assets and income to determine how each should be treated. Accordingly, IRC Sections 2031 through 2046 (and in particular, IRC Sections 2036 – 2042) are used to determine when trust (and other) assets will be included as part of the gross estate for estate tax purposes. In turn, IRC Sections 671 through 678 are used to determine when trust (or other) income will be treated as the grantor’s for income tax purposes.

And while the retained powers or interests that determine estate inclusion are similar to those that determine income tax inclusion, they are not identical. For instance, under IRC Section 677(a)(3), the power to use trust income to pay premiums on a life insurance policy on the life of the grantor or his/her spouse will cause the income to be treated as the grantor’s for income tax purposes, but would not cause the trust assets to be included for estate tax purposes. Similarly, a so-called “substitution power” under IRC Section 675(4)(C) – which allows the grantor to swap personal assets with trust assets, as long as the substitute asset has equivalent value – also causes the trust’s income to be treated as the grantor’s for income tax purposes, but usually will not cause the assets to be included for estate tax purposes (though complications can arise if the trust owns a “controlled corporation” family business). A third option is to allow the grantor the power under IRC Section 675(2) to borrow from the IDGT without providing any security for the loan (or at a below-market interest rate), which again triggers grantor trust status.

Thus, the whole purpose of how an IDGT trust is structured is to deliberately have the trust document be limited enough that trust assets will not be included in the grantor’s gross estate for estate tax purposes, but to include one of the aforementioned powers that means the trust will be treated as the grantor’s for income tax purposes. Or viewed another way, the IDGT is “effective” at removing the trust assets from the grantor’s estate, but “defective” at removing the trust’s income from the grantor’s tax return.

Installment Sales Of High-Return Assets To An IDGT

Ultimately, the benefit of structuring an IDGT with its unique combination of income-tax-included but estate-tax-excluded treatment is not only that the grantor can pay the income tax liabilities of the IDGT – allowing it to grow more rapidly outside the estate by not being required to pay its own tax burden – but also because as a grantor trust it may still own a subchapter S corporation (a common corporate structure for many family businesses). And even more important, the fact that the IDGT is treated as the grantor’s “alter ego” for income tax purposes allows the grantor to make special arrangements to get a large amount of assets into the trust.

After all, one of the significant constraints of trying to put assets into a trust that will be outside of the grantor’s estate is that transferring assets into the trust will itself be treated as a gift, which means either paying gift taxes, or at least using a portion of the contributor’s lifetime gift and estate tax exemption amount (currently $5.45M in 2016). Thus, from a practical perspective, it would be difficult to get property valued at more than $5.45M (or $10.9M for a married couple that splits the gift) into an IDGT, without triggering substantial gift tax consequences (and while there are situations where it is beneficial to ‘cause’ gift taxes during life, at a minimum that is a much higher stakes transaction).

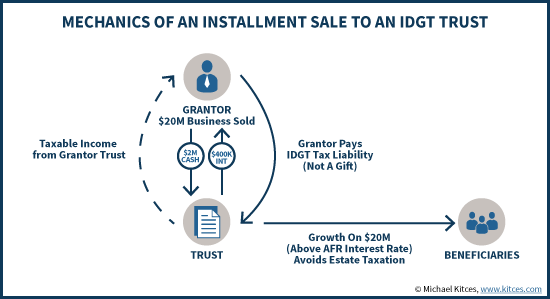

So what’s the alternative? Instead of simply gifting assets into the IDGT, the grantor sells a (high-return) asset to the IDGT instead. Under Revenue Ruling 85-13, a sale by a grantor to his/her grantor trust in exchange for an interest-bearing promissory note is not treated as a taxable event for income tax purposes – effectively, allowing the grantor to swap a bond (the promissory note) for a stock (or whatever other asset the grantor wants to get into the IDGT) without triggering any capital gains taxes on the sale itself.

Example. Jeremy is the founding owner of a business worth $20M, which generates about $1.5M to $2M/year in profit distributions. As a result, Jeremy has a significant estate tax problem (he is far above the $5.45M exemption amount), which will only get worse as the business distributes ongoing profits (and especially if the stock appreciates further). Jeremy could gift about 25% of the business to family members or an irrevocable trust, eliminating that portion of the business value and its subsequent growth from his estate, but he’d still be stuck with the other 75%.

Instead, Jeremy sells the business to the IDGT instead, in exchange for a promissory note from the trust that agrees to make interest-only payments of 2%/year for the next 15 years (followed by a balloon payment of the principal). At this interest rate, the trust will only need to make $400,000/year of interest payments, which is easily covered by the available cash from the business’ $1.5M+ profit distributions.

Immediately after the transaction, Jeremy’s net worth and estate tax exposure have not changed. He’s simply swapped from a family business worth $20M, to a promissory note worth $20M instead. Since he’s sold the business to “himself” for income tax purposes, there are no capital gains taxes due on the transaction, and cost basis of the business simply carries over into the trust.

However, going forward, the promissory note will “grow” by its simple 2% yield, while the business is already producing almost 4X that amount of cash flow, plus the potential for the business to appreciate further (while the promissory note’s principal value is fixed).

For instance, if at the end of the first year, the business appreciated to $21M (e.g., by getting a big new customer), plus generated profits of $1.5M, and then paid out $400k in interest, its value would be up to $22.1M. By contrast, the grantor’s estate would still be $20M, plus the $400k of interest, but reduced by the income tax liabilities it must pay. The end result is that the trust’s value finishes over $22M, while the grantor’s estate will be slightly lower than $20M, producing a $2M shift in value to the trust – and outside the grantor’s estate. At a 40% top estate tax rate, that’s an $800,000 estate tax savings!

In other words, the end result of the sale-to-IDGT transaction is that the owner’s estate is not reduced directly (because the value of the promissory note itself is still included in his/her estate), but a potentially-high-return investment is transmuted into a low-return bond… such that the difference between the long-term return of the promissory note (with a 2% yield) and the original business or other investment (e.g., growing at 8%) is shifted outside of the grantor’s estate, without being treated as a (potentially taxable) gift.

And notably, in the example above, the grantor managed to push not just the growth on 25% of the business out of his estate (the result if he simply gifted up to the $5.45M gift and estate tax exemption), but the growth on all 100% of the business!

Requirements For A Legitimate Installment Sale To An IDGT

It is perhaps not surprising that given the substantial potential estate tax savings available with an installment-sale-to-IDGT strategy, the IRS will scrutinize the transaction to affirm that it is a legitimate sale transaction and not merely an indirect gift of the business to the trust (or alternatively that the grantor is deemed to have retained some power or right that would cause the IDGT to be included in his/her estate after all).

The first requirement for an IDGT to be respected is that the promissory note itself must use a legitimate and not “below market” interest rate (even though the grantor may have the power to borrow from the trust later at a below-market interest rate, in order to trigger grantor trust status in the first place). Under IRC Section 7872, a “below market” rate loan is defined as one that fails to use the published Applicable Federal Rates (AFR) of IRC Section 1274 (which, notably, is lower than the 7520 rates that must be used as the discount rate for a GRAT for short- or mid-term loans). Fortunately, though, given the overall low interest rate environment today, the required AFR to include with the promissory is still extremely low – even for “long-term” loans that will extend more than 9 years, the AFR is just a mere 1.90% (as of August 2016). Which provides a rather easy total return hurdle rate that the assets sold to the IDGT to need to clear.

The second requirement is that in order for the IRS to respect the sale transaction, the IDGT itself should already have some (liquid) assets. After all, who would realistically sell their business to a third party that has no income, no assets, and makes no downpayment? Accordingly, it is common practice to “seed” at least 10% of the expected purchase price into the IDGT as a separate gift before the sale transaction occurs (this approach dates back to PLR 9535026 where a version of the IDGT strategy was affirmed by the IRS). The assets aren’t necessarily used for a downpayment, but at least help to secure the ability of the IDGT to make the initial installment note payments, until the business transferred into the IDGT can generate enough cash flow to pay its own way from there.

Notably, this requirement to seed the trust with some assets, in order to be able to substantiate the subsequent installment note sale, means that the grantor will still end out using at least some portion of his/her lifetime gift tax exemption. Still, given a need to seed “just” 10% of the targeted purchase price, this still means the owner of a $20M business would just need to gift $2M to the trust to do the subsequent installment sale to the IDGT that removes the growth from all $20M. In practice, the $2M gift will typically be done with cash or otherwise reasonably liquid assets, to further substantiate that the trust really has the (liquid) means to make payments on the installment note. Though ultimately, doing so allows all growth above that required AFR interest rate to occur outside of the grantor's estate (and therefore avoid any estate tax exposure!).

Third, the valuation of the business itself (or whatever is being sold to the IDGT) should otherwise be reasonable and substantiated. If the sale-to-IDGT transaction is not for the full value of the business (or other asset being sold), the IRS may recharacterize the transaction as being part-sale and part-gift, which can accidentally absorb most/all of the grantor’s remaining gift tax exemption, or even trigger a taxable gift for the excess (in the case of very large IDGT transactions). Notably, though, bona fide valuation discounts – including for lack of control (minority ownership) and lack of marketability – may still be considered. Though recently proposed Treasury Regulations to crack down on a wide range of discounts on family partnerships and other intra-family transactions could soon end such valuation discounts, including in most sale-to-IDGT transactions.

For grantors who actually do want to remove not just the growth on the business asset, but also the value of the asset itself, it’s also possible to use a Self-Cancelling Installment Note (SCIN) for the sale to the IDGT as well. The significance of a self-cancelling installment note is that when the grantor dies, the remaining value of the note goes to $0 (i.e., it is “self-cancelling”). The “bad” news is that with a SCIN, the required payments from the IDGT back to the grantor will be higher (or the purchase price should be higher in the first place), as an objectively valued SCIN should offer larger payments to compensate for the risk that the value goes to $0 if/when the grantor dies (i.e., the pricing of the SCIN transaction should reflect a risk premium for the risk of the grantor’s death). The “good” news, though, is that because the SCIN’s value is reduced to zero at the grantor’s death, the entire value is eliminated from his/her estate. To ensure the SCIN is respected, though, the grantor must actually be in reasonable health, such that the SCIN and its payments are legitimately valued given their uncertainty. Doing an IDGT sale for a SCIN with a grantor who was already in poor health and expected to die within a year or two would rapidly evaporate significant value from the grantor’s estate, but would not likely be honored by the IRS (given that no rational person outside an estate tax avoidance strategy would ever sell a business for full value in exchange for a SCIN that was only likely to ever make 1-2 annual payments!).

Could The IDGT Strategy Someday Be Eliminated?

While the IDGT strategy and its legitimacy are now well established – at least as long as the aforementioned requirements are met – it is nonetheless an estate planning strategy that the IRS and Treasury are concerned about. Because it does effectively allow high-net-worth individuals to ‘magically’ transmute their stocks (i.e., businesses or actual portfolio stock investments) into low-rate fixed-yield bonds, shifting all of the equity growth to occur outside of the estate, at a tax cost of zero (beyond using a portion of the lifetime gift tax exemption to fund the seed amount to the IDGT, given that there’s not even a capital gains tax event on the sale of the business to the IDGT).

And in today’s interest rate environment, where the Applicable Federal Rate “hurdle rate” is so low, the potential for estate tax savings of using an IDGT is substantial, despite the fact that the individual who owns the assets doesn’t have to take any substantive economic risk to get the benefits (beyond the risks already inherent in owning a high-return high-risk business or similar asset).

Accordingly, back in 2012, President Obama’s budget proposals published in the Treasury Greenbook included a recommendation that automatically treat any trust that was a grantor trust for income tax purposes as also being included in the grantor’s estate as well, effectively eliminating the subtle differences between IRC Sections 2036 – 2042 and Sections 671 – 678 that previously made it possible for trust income to be taxed to the grantor but trust assets to be treated as outside the grantor’s estate. Ultimately, the proposal was not implemented – in part because such a wide-reaching provision would adversely impact a number of other non-abusive trust strategies that are grantor trusts, including the Irrevocable Life Insurance Trust (ILIT) and Charitable Remainder Trust (CRT). Nonetheless, the next year a modified version of the proposal appeared again in the Treasury Greenbook, more narrowly suggesting that any assets sold to a grantor trust would automatically be brought back into the grantor’s estate, which again would kill the IDGT strategy (but not other types of trusts); this version of the proposal too has not yet been implemented, but it has continued to be re-proposed in the President’s budget proposals, emphasizing that this is a strategy on the radar screen in Washington DC for potential crackdown in the future.

Until a crackdown is implemented, though – which in all likelihood would only be forward-looking anyway, and not retroactive to already-implemented IDGTs, given the practical challenges of trying to recharacterize transactions after the fact – the IDGT strategy remains legitimate, as long as its rules are respected.

For the time being, the IDGT strategy remains most effective for those who are substantially above the estate tax exemption amounts, who have a high-return asset (whether a business or potentially even “just” a portfolio of equities) that can be transmuted into a low-return bond (at today’s low yields) to shift the excess growth and appreciation out of the grantor’s estate. In essence, the IDGT is an “estate freezing” strategy, that locks in the value of the business or other high-return asset at its current value (plus just a small nominal yield), while eliminating future estate tax exposure on the growth. For the time being, the strategy can be further leveraged by obtaining a valuation discount (whether for a family business, or forming a family limited partnership in order to obtain such a discount), though again the days for discounts on family entities are likely numbered now, and may be gone by sometime in 2017.

Though notably, because the long-term value is really for the future growth to shift out of the grantor’s estate and into the IDGT – not merely the discount on the business going into the IDGT in the first place – the sale-to-IDGT approach will remain effective even without valuation discounts, as long as there’s a long time horizon to compound, and especially when low interest rates can be locked into the long term of a promissory note.

So what do you think? Have you even done an installment sale to an IDGT for a client? What type of asset did you put into the trust? How did you explain the strategy, and were there any surprises? Please share your thoughts in the comments below!