Executive Summary

Financial advisors have a wide range of strategies at their disposal to create financial plans for their clients. And when it comes to retirement planning, one popular technique is the use of ‘guardrails’, which set an initial monthly withdrawal rate that can be later adjusted as the size of the client’s portfolio changes. This strategy is valuable because it generally allows for higher initial withdrawal rates than more static approaches that don’t accommodate clients willing to adjust their spending in retirement. However, given the technical nature of the guardrails approach, advisors can find it challenging to explain to prospective and current clients how it will work in practice.

To start, it is typically preferable to explain guardrails to prospects and clients in dollars rather than in percentage terms (e.g., telling the client they can safely withdraw $4,500 each month rather than saying they will have a 5.4% annual withdrawal rate). Further, given that a client’s monthly distributions will almost certainly change at some point when implementing a guardrails strategy, they must understand what this means in practical terms. To help them do so, advisors can explain that when market returns are strong, they can take larger distributions each month (in dollar terms), but when an inevitable bear market arrives, they may need to cut back on their monthly income until things get better. In addition to explaining withdrawals in dollar terms, advisors can also present a client’s asset allocation in dollar terms (instead of the more usual approach of explaining the allocation in percentages) by framing it as the number of years of income that would be protected from stock market fluctuations (e.g., setting aside a ‘war chest’ of cash and fixed income balances to provide 5 years’ worth of income).

While most clients will have no problem accepting a larger monthly income, tightening their belts will be more challenging. One way to prepare clients for a potential reduction of their monthly income is to give advance warning that a cut might be necessary if their portfolio declines further (and to encourage them to consider where they would cut back if needed). In the case of a market downturn, advisors can wait an agreed amount of time (e.g., 2 quarters) after the client’s portfolio balance falls below the lower guardrail before implementing an income reduction, as this can give the market time to recover and preclude the need to make any adjustment at all (and is still more conservative than the annual review prescribed in the initial guardrails research). If the portfolio balance declines due to excess distributions (e.g., a lump-sum withdrawal to buy a new car), advisors can advise clients on whether withdrawals will bring them closer to (or even dip below) the lower guardrail and the implications for their future monthly income.

Ultimately, the key point is that while a guardrails strategy can help clients maintain sustainable withdrawal rates throughout retirement, ensuring that clients understand how the strategy applies to them – in practical terms – is essential for success. Advisors can do this by explaining withdrawal rates, guardrails, and potential future changes in spending and income, all in dollar (rather than percentage) terms. Furthermore, by giving clients advance warning of potential changes, advisors can help clients feel confident about the guardrails strategy and, perhaps more importantly, in their advisor’s ability to implement it!

Discovering Jonathan Guyton and William Klinger’s strategy for dynamic distribution rates during retirement (and then figuring out how to translate it for clients) was perhaps the 2nd most impactful moment in my career, as it led to the guardrails deliverable that I developed for my own clients, which has been the foundation of every one of the 1,000-plus client and prospect meetings I’ve conducted since then (circa 2012).

Prior to recording my Nerd’s Eye View Financial Advisor Success Podcast episode in February 2017, I had never personally met anyone using guardrails in their practice. But since then, there have been many articles and podcasts popularizing their use, moving guardrails from the back pages of The Journal of Financial Planning to a mainstream strategy being discussed and implemented broadly across the industry.

What Exactly Are Guardrails?

Known in academic circles as ‘Dynamic Distribution Rates’, guardrails are a strategy for adjusting monthly distributions based on a percentage of the overall portfolio value. A full review of Guyton & Klinger rules is beyond the scope of this article (especially as they’ve been written about dozens of times), but the basic 4 rules are loosely summarized as follows:

- Portfolio Management Rule. Distributions are taken from overweighted assets (equities followed by fixed income), then cash, then, if necessary, underweighted assets (fixed income followed by equities).

- Inflation Rule. Following years of positive market returns, the distribution amount is increased to match the prior year’s inflation number, up to a cap of 6%.

- Portfolio Preservation Rule. If the current distribution rate has increased by more than 20% of the initial rate due to portfolio value declines (resulting from market conditions and/or distributions), the distribution amount is decreased to ‘preserve’ the portfolio.

- Prosperity Rule. Essentially the opposite of the preservation rule, if the distribution rate has decreased by more than 20% of the initial rate due to portfolio value increases (market growth and/or contributions), the distribution amount is increased.

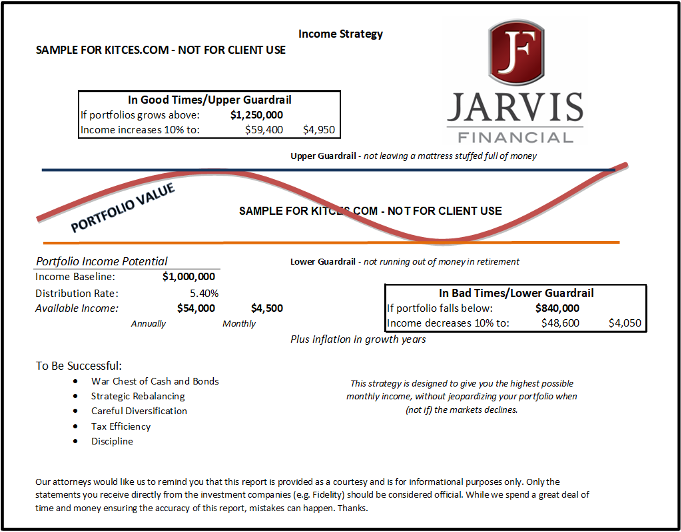

For example, an advisor using a 5.4% distribution rate on a $1 million portfolio would calculate annual distributions of $54,000 ($4,500 monthly). So, according to the Prosperity rule (i.e., avoiding leaving a mattress stuffed full of money) and the Preservation rule (i.e., never running out of money), the guardrails would be set at +/– 20% of the original distribution rate of 5.4%.

This means that if distributions and/or market movements change the portfolio value such that the original distribution rate exceeds 5.4% + (5.4% × 20%) = 6.5% of the new portfolio value, a cut is needed; conversely, if the distribution rate falls below 5.4% – (5.4% × 20%) = 4.3%, an increase is allowed.

Nerd Note:

Guyton & Klinger assigned a 99% confidence standard for initial withdrawal rates between 5.2–5.6% for portfolios with at least 65% equities, assuming all 4 of the decision rules they tested were applied to the portfolio. This is in contrast to the lower initial withdrawal rates closer to 4%, popularly advocated in the 1990s by financial adviser Bill Bengen.

All this math translates into the following discussion with prospects and clients whenever our discussions turn to portfolio income:

Mr. & Mrs. Client, the biggest question every client has when approaching retirement is: “How much can I safely take from my nest egg so that I can be sure I never run out of money?”

Unfortunately, this question is not easy to answer, as there are 2 critical variables that are impossible to determine. The first variable includes future stock market trends, interest rates, inflation, and even tax policies. The second equally critical and equally unknowable variable is how long you will be retired, which is a nice way of saying how long you will live. If we knew how to determine either of these variables, let alone both of them, this would be easy.

But because we can’t predict the future and don’t know either of these variables, we will start out with a monthly retirement income based on what would have worked during the worst historical scenarios and then adjust it up and down as needed based on what actually happens.

However, going deeper into an explanation of how guardrails actually work and telling someone that “the capital preservation rule applies when a current year’s withdrawal rate – using the decision rules in effect – has risen more than 20% above the initial withdrawal rate” is almost guaranteed to make their eyes glaze over. This is where, as advisors, we have to translate academic jargon into plain English.

Nerd Note:

The goal of this article is to share how advisors can communicate with their clients so that they understand guardrails strategies based on the original work of Jonathan Guyton & William Klinger. Several past articles have offered a more technical discussion of various guardrails strategies, from developing a probability-of-success driven retirement guardrails strategy to implementing a holistic risk-based guardrail strategy, illustrating dynamic income planning through spending risk curves and adjustment plans, and even applying gamification research to probability-of-success strategies and Monte Carlo simulations.

How To Discuss Guardrails With Clients To Help Them Understand What They Mean

As is often the case, the simplest explanation for clients, when it comes to financial planning topics, is one that boils down to dollars. In the case of guardrails, it’s the distribution amount, the portfolio value, and the values of the upper and lower guardrails.

For example, explaining how guardrails (expressed in dollars) will impact the amount of their monthly distributions (again, expressed in dollars) helps clients develop a concrete understanding of how the strategy will affect their retirement income:

Mr. & Mrs. Client, so long as your portfolio value stays between approximately $800,000 and $1,200,000, you are safe taking $4,500 monthly.

When, not if, we fall below the lower guardrail of $800,000, we will need to temporarily tighten our belts and reduce your income by about $500 a month. Is that OK with you?

The use of a guardrails strategy can involve explaining to clients the idea of having ‘extra’ income during good times and having to tighten their belts during bad times. Either way, ensuring that clients are equipped with a clear framework for handling cash flow is just as critical for advisors as having a solid understanding of how Guyton & Klinger’s rules work, along with a practical system for generating deliverables that clients will understand.

Also of equal importance is having the fortitude and relationship capital with clients to actually make cuts when portfolio values fall below the lower guardrail, which can be especially difficult in the face of high inflation. We approach these conversations from 2 perspectives: breaking the lower guardrail because of market declines or because of over-distributing from the portfolio.

Guardrails In ‘Good’ Times: Explaining Higher Distributions When Portfolio Values Remain Within Guardrail Boundaries

For advisors using guardrails over the last several years (really since the end of the Financial Crisis in 2009), guardrails have been a very rewarding retirement income strategy. After all, using Guyton & Klinger’s recommended distribution rates (i.e., 5.2−5.6% for portfolios with at least 65% equities), advisors and their clients have been able to take significantly more income than the traditional 4% fixed distribution rate.

In my own practice, we’ve used a slightly modified version of Guyton & Klinger’s rules, with most clients taking a dynamic 5.4% distribution rate. To put this in dollars (because, as noted earlier, talking in dollars – and not percentages – is usually more meaningful for clients), a $1,000,000 portfolio with a 5.4% distribution rate translates into $4,500 each month versus just $3,333 with a strategy using a fixed distribution rate of 4%.

When explaining to clients how this will work when things are going well, advisors can emphasize the fact that their distributions are higher than what would traditionally be recommended, along with describing what it means when their portfolio balance dips down past their lower guardrail.

Such a client conversation might start something like this:

Mr. & Mrs. Client, in retirement, we use a ‘dynamic distribution rate’ which is a fancy way of saying that when times are good, we will take a little extra each month, but when, not if, times are bad, we will cut back until things get better. Because of the exceptional job you have done saving a $1 million nest egg, we are safely able to take $54,000 annually, or about $4,500 monthly.

This is about $1,000 more each month than what an advisor using a more traditional ‘4% rule’ might recommend. The reason most advisors don’t use this approach is that it requires a lot more work to manage (which is why you hired us), but it also requires that when, not if, markets decline, you are willing to take a temporary pay cut until things get better.

In your situation, you are good to take $4,500 monthly until your nest egg falls below about $800,000. When this happens, we would temporarily reduce your income to about $4,000 a month, which might mean skipping a vacation that year or eating out less, which won’t be fun, but in all the good years, you’ll be able to enjoy an extra $1,000 a month. Is that OK with you?

In my practice, we’ve very successfully used this strategy for clients with assets ranging from $200,000 to $10,000,000+. In other words, don’t let the dollar amounts distract you. I’m using $1,000,000 in all these examples because it makes the math easy.

Guardrails In ‘Bad Times’: Breaking The Lower Guardrail Due To Market Conditions

When the portfolio balance dips below the lower guardrail, when do we actually make cuts? For most guardrails researchers, including Guyton & Klinger, withdrawal rates based on the various decision rules are recalculated on an annual basis, resulting in annual spending adjustments. This is likely for simplicity’s sake in managing historical and Monte Carlo data.

However, in my own practice, we review guardrails quarterly (and only quarterly, except in cases of major portfolio net flows); if/when clients fall within 10% of their lower guardrail, we take note, and during their next routine meeting, our conversation to explain the situation will go something like this:

Mr. & Mrs. Client, as you can see, your current balance of $900,000 puts us less than $100,000 away from the lower guardrail.

No need to make changes today, but if the markets get worse before they get better, we will need to temporarily reduce your monthly income from $4,500 to about $4,000.

I would encourage you to take a look at your spending to get an idea of where you would make this temporary reduction. Is that OK with you?

In the event a client falls below the lower guardrail due to market conditions, we will wait 2 calendar quarters before insisting on a change. This 2-quarter approach helps avoid cutting income during volatile periods (e.g., March 2020). If, after 2 quarters, the client’s accounts remain below the lower guardrail, we have the following discussion:

Mr. & Mrs. Client, as you likely know, the markets have been very rough this year. While all of history tells us they will recover, eventually, until they do, we need to temporarily reduce your income. Would you like us to reduce it on your next distribution or the one after that?

Regardless of the frequency an advisor may choose to implement for clients, it is critical that guardrail reviews be systematized so that they are reviewed consistently; this will ensure that adjustments to guardrail values and client spending levels are made when necessary.

Guardrails In ‘Bad Times’: Breaking The Lower Guardrail Due To Excess Distributions

Market conditions are not the only reason a client’s account will fall below the lower guardrail. In scenarios where a client is taking lump sums and/or monthly payments in excess of the guardrail amount, we will immediately take action to help the client get back on course in the form of resetting their monthly income based on the new portfolio value.

We communicate with clients to explain what this means to their monthly income:

Mr. & Mrs. Client, over the last year, you’ve pulled out some $200,000, which has pushed your portfolio value below the guardrails.

The good news is that we can easily update your guardrails to reflect your new balance. Going forward, based on your current balance of $800,000, your new safe withdrawal rate is $3,600 monthly.

Helping clients make specific cuts to their budgets to accommodate the new safe withdrawal rate is beyond the scope of this article. In my office, we rarely look at a client’s budget as we typically only work with clients who understand that living within their income is non-negotiable. In the rare case where our clients need help with them, we recommend they read Total Money Makeover by Dave Ramsey and/or study the Mr. Money Mustache blog.

Helping clients make specific cuts to their budgets to accommodate the new safe withdrawal rate is beyond the scope of this article. In my office, we rarely look at a client’s budget as we typically only work with clients who understand that living within their income is non-negotiable. In the rare case where our clients need help with them, we recommend they read Total Money Makeover by Dave Ramsey and/or study the Mr. Money Mustache blog.

If the client feels they are unable to adjust to this new sustainable income and our efforts to help them cut spending fail, it is, unfortunately, time for a much more serious discussion:

Mr. & Mrs. Client, one of my most important jobs as your advisor is to make sure you never run out of money in retirement.

By taking more than a sustainable amount from your portfolio, the risk of you running out of money goes up so dramatically that I must insist you make the adjustment.

Unfortunately, this is such an important decision that if you are unable to make the change, I will, with great sadness, be forced to resign as your advisor, as I refuse to watch a client run out of money.

While some advisors may feel that graduating a client for over-distributing is too severe, in my mind, it is non-negotiable on both ethical and liability grounds. Ethically I cannot stand by while a client makes what I consider to be crippling financial decisions. From a liability standpoint, clients who over-distribute will likely run out of money and, to paraphrase the words of Nick Murray, I refuse to captain a sinking ship; because when the ship does sink, and the client (or their family) is looking to place blame, I don’t want to be anywhere near the proverbial wheel.

Of course, life is rarely this simple, and breaking the lower guardrail is often a combination of excess distributions and market conditions. In these cases, the advisor must step up the table and decisively advise on the best course of action.

What Happens After The First Income Cut

As noted above, we approach breaking the lower guardrail from 2 scenarios: market declines and over-distributing. In both cases, once a new, lower income level is established, the guardrails are reset relative to this new level.

In other words, if our client’s original monthly income is $4,500 (based on a 5.4% withdrawal rate from a $1 million portfolio value) and their portfolio value falls below the lower guardrail of $833,000, their new income would be reset to $4,050 (reflecting a 10% cut from their original income amount).

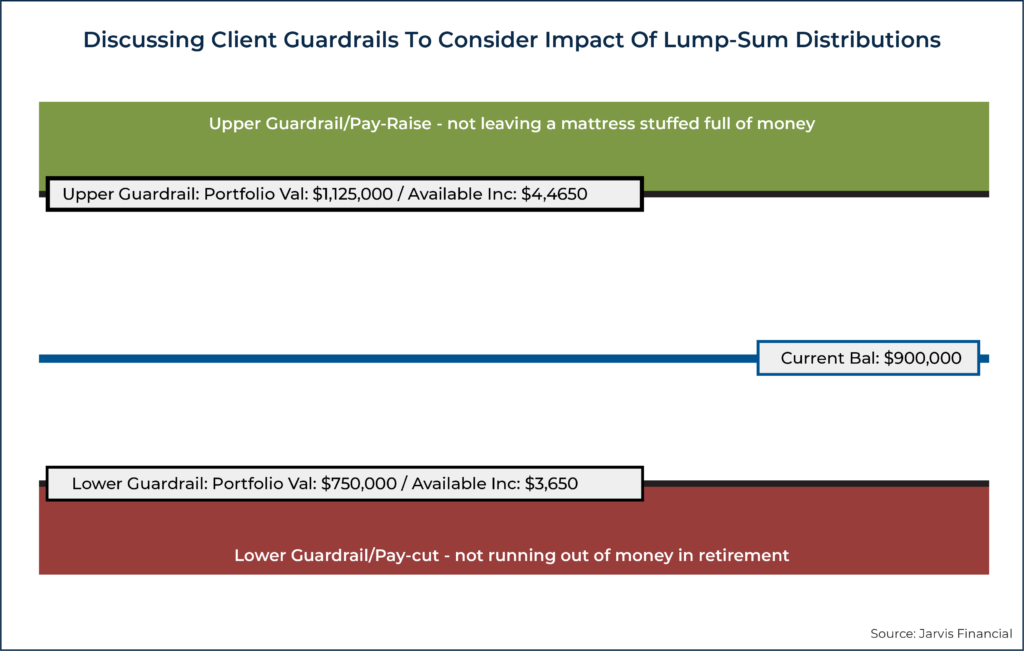

While not purely true to the Guyton & Klinger rules, with this new income, we essentially reset the guardrails illustration as if they had always been distributing $4,050 each year ($48,600 annually), which would give us a portfolio baseline balance of $48,600 ÷ 5.4% = $900,000, an upper guardrail balance of $48,600 ÷ (5.4% + (5.4% × 20%)) = $1,125,000 and a lower guardrail balance of $48,600 ÷ (5.4% – (5.4% × 20%)) = $750,000. This ‘reset’ makes it easier for the client to understand and, admittedly, easier for our office to track. After all, if the client can’t understand it (or the advisor can’t efficiently track it), it likely won’t be implemented successfully.

When this reset happens, we clearly explain to the client (just as we do in every meeting) that if/when we were to hit this new lower guardrail, we would again need to make a cut. Depending on a number of variables, Guyton & Klinger estimated clients would experience 2–5 cuts during a 40-year retirement. As such, we must carefully manage client expectations that multiple cuts could be required to ensure they never run out of money in retirement.

Those readers well-versed in Dynamic Distribution rates may note that my approach doesn’t exactly comply with the rules (e.g., quarterly versus annual adjustments, resetting the entire Guardrails when broken, talking about portfolio balance versus distribution rate, automatic inflation adjustments, etc.) and that my numbers are constantly rounded. These deviations are deliberate, though, and emphasize the challenge of applying academic principles to real client circumstances.

While we certainly could track/implement more precisely, the realities of running a hyper-efficient practice require diligently examining every decision on its cost/benefit. And perhaps we could squeeze out a few extra dollars of income for the client with a different approach, but if doing so burns out our team, client service is compromised and nobody wins.

More Than Just An Income Strategy, Guardrails Are A Powerful Visual Tool That Can Provide A Spending Framework For Clients

In addition to the extra income in retirement that clients could potentially receive using a higher withdrawal rate (relative to the more conservative rates popularly recommended in earlier decades), guardrails provide a visual framework for not only how much a client can safely take but also when and how adjustments will need to be made.

During relatively minor declines, guardrails easily illustrate how much buffer the client has between their current portfolio value and the lower guardrail. It also provides a framework for helping clients make an educated and informed decision on taking lump sum distributions, such as $100,000 for a major purchase.

Prior to implementing guardrails in my practice, discussions around whether it would make sense for a client to take a lump-sum distribution, especially during market declines, were much more difficult and vague, as the answer previously revolved around the client’s probability of success shifting from 87% to 72%, neither of which helps clients understand how that translates into the actual consequences to their financial plan and spending habits.

Today, though, with the availability of guardrails-based visual tools, we can easily discuss lump-sum distributions and how they might impact the client’s plan. For example, such a conversation might start like this:

Mr. & Mrs. Client, the great thing about how we have your portfolio set up is that it is extremely flexible. If you wanted to take out a lump sum of $100,000, we simply need to see how that would impact your guardrails…

…as you can see, your current balance is $900,000 and your lower guardrail is $750,000. This currently provides a $150,000 buffer, which means you can easily take out the $100,000. It does, however, put us closer to the lower guardrail, which means that when, not if, the markets decline, we would be that much closer to needing to take a pay cut.

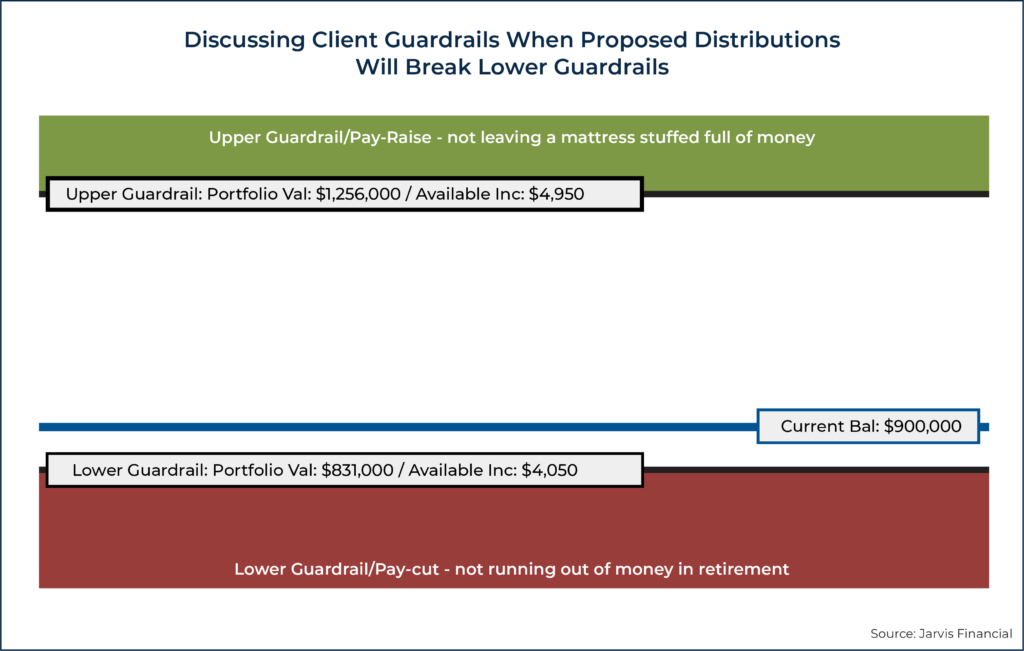

Alternatively, if a lump-sum distribution would result in going beyond the client’s lower guardrail, we could instead frame the discussion as follows:

Mr. & Mrs. Client, if you wanted to take out a lump sum of $100,000, we simply need to see how that would impact your guardrails…

…as you can see, your current balance is $900,000 and your lower guardrail is $831,000. Taking $100,000 will put us at $800,000, below the lower guardrail, which means we will need to reset your monthly income to ($800,000 × 5.4%) ÷ 12 = $3,600. As long as you are OK with this new income level, we can process the distribution without delay.

How To Implement A Guardrails Process To Use With Clients At The Firm Level

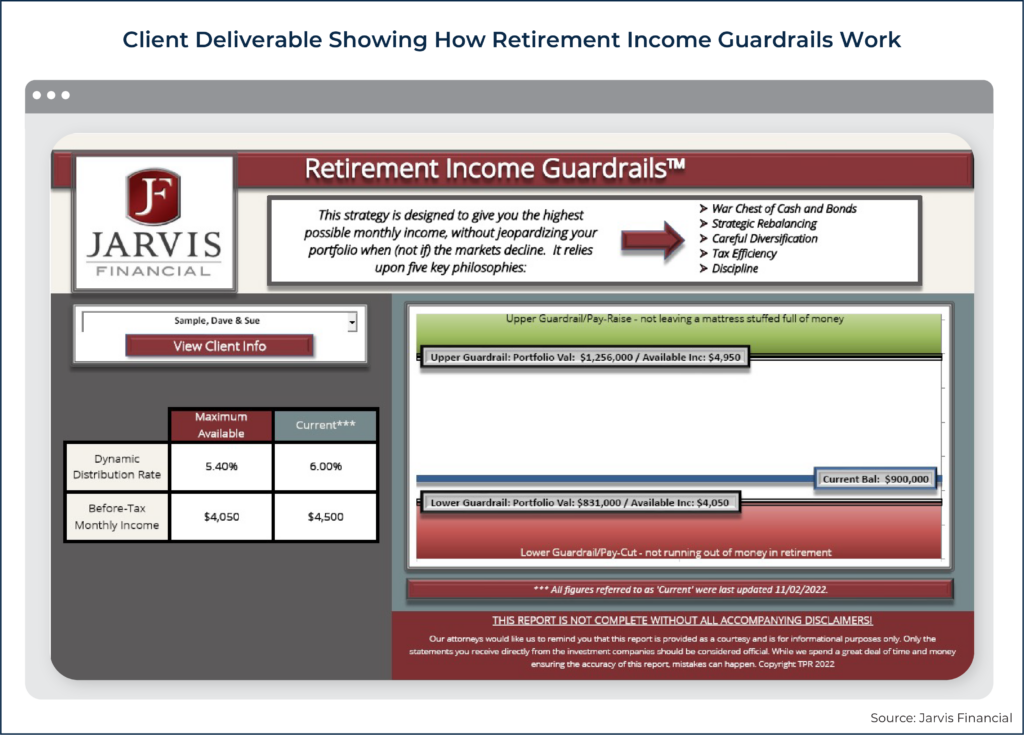

For years, we ran all of our analyses to develop client guardrail strategies using an Excel spreadsheet that allowed us to update the client’s data easily and provide them with a visual deliverable:

Each quarter we would update the spreadsheet with portfolio values and distributions. And by using some basic conditional formatting, we could visually see who was approaching or below the lower guardrail. Before every client or prospect meeting, my team would generate updated guardrails for my review and use in the meeting.

Of course, Excel has its limitations with formatting, tracking changes, and auto-importing. And once macros were added, it became very fickle. So instead of leaving well enough alone, my good friend (and co-founder of The Perfect RIA) Micah Shilanski and I invested a large 6-figure sum in creating a web-based platform that we use in our respective practices and the practices of our coaching clients, with the intent to share this resource with the entire industry.

Using Orion’s trading software, Eclipse, we manage the portfolios according to Guyton & Klinger's rules, paying special attention to cash and fixed income balances. We describe these balances to clients as their “War Chest”, which, in line with everything else related to guardrails, we communicate in dollars (and never percentages).

Firmly in the realm of jargon, ‘fixed income’ is a term we seldom use with clients and instead refer to it as ‘years of income in our war chest.’ Depending on a client’s ability to stay the course (which no questionnaire can truly assess) and their ability to adapt their spending to cuts dictated by the guardrails, we will adjust the war chest to provide between 4 and 8 years of income (e.g., 20% to 40% in fixed income). With this years-of-income framework, we can talk to clients about the number of years of buffer they want to have to help them survive through bear markets versus the more traditional (and much less useful?) question, “How will you feel when the markets decline 20%?”.

And to minimize the frequency of needing to trade in accounts, we keep 9–12 months of distributions in cash. Each calendar quarter, we look for opportunities to harvest growth in equities to replenish the War Chest.

In the current market conditions, where nearly all equities are down, we are currently drawing down the fixed-income side of the portfolio to cover distributions. This can be a little tricky to manage logistically as the default would be to rebalance back to the original model (e.g., 70/30), which would typically reduce the dollars in the War Chest and, thus, the years of income available.

An example of how we would introduce clients to these concepts might go as follows:

Mr. & Mrs. Client, you’ve been investing towards retirement for a long time, and you know from experience that the next market decline, sometimes called a ‘bear market’, is a matter of when, and not if.

While bear markets are never fun, they can be especially destructive in retirement due to reverse dollar-cost averaging. In other words, the further down the markets go, the more shares have to be sold to cover your monthly income, which can result in your nest egg never being able to recover.

To help prevent this, we are setting aside 5 years’ worth of income in what we like to call your ‘War Chest’. While 5 years of income might not get us all the way through a bear market, it would get us past the worst of it without having to sell equities at a loss.

To put this in historical context, the War Chest would have easily gotten us through the COVID panic of 2020, but it also would have gotten us through the worst of the financial crisis of 2008–2009.

Once advisors figure out the right tool to systematically implement guardrails in their practice, they should find a way to explain to clients why they are introducing a new tool. Be it guardrails or any other new system I present to clients, I always lead with a conversation that goes something like this:

Mr. & Mrs. Client, do you remember buying your first CD player? What an incredible upgrade from the tapes and records we used previously.

Despite this leap in technology, when was the last time you used a CD player? Just like your CD player, the strategy we’ve been using was the best there was at the time we recommended it. Now there is a better way, and it is…

Guardrails, of course, are just one piece of Delivering Massive Value to clients or prospects, and these scripts are just one piece of guardrails. Ultimately the success of guardrails in your practice for your clients will depend not just on understanding how guardrails-based strategies work, but also on being able to communicate them effectively and with confidence to clients!

If you found these real-world scripts helpful, please leave a comment below with your thoughts, questions, and/or different scripts that you’ve found helpful when sharing complex topics with clients. Additionally, click here if you’d like to join The Perfect RIA's mailing list and receive a free video demonstration of me presenting guardrails to clients.

Happy Planning!