Executive Summary

As the retirement income research evolves, an increasingly common question is whether the popular safe withdrawal rate approach is better or worse than an annuity-based strategy that provides a guaranteed income floor, with the remaining funds invested for future upside.

Yet the reality is that as it's commonly applied, the safe withdrawal rate strategy is a floor-with-upside approach, too. Unlike the annuity, it doesn't guarantee success with the backing of an insurance company; yet at the same time, the annuity is assured to provide no remaining legacy value at death, while the safe withdrawal rate approach actually has a whopping 96% probability of leaving 100% of the client's principal behind after 30 years!

Which means an annuity is really an alternative floor approach to safe withdrawal rates - one that provides a stronger guarantee while producing a similar amount of income, but results in a dramatic loss of liquidity, upside, and legacy. Does the common client preference towards safe withdrawal rates and away from annuities indicate that in the end, most clients just don't find the guarantee trade-off worthwhile for the certainty it provides?

The inspiration for today's blog post is a recent email correspondence I had with retirement researcher Wade Pfau, discussing the traditional life-cycle finance economist approach to retirement planning that typically focuses on first securing a guaranteed income floor to cover essentials, and then providing for additional discretionary expenses with a more growth-oriented investment option (since discretionary expenses by definition can be flexible and adjust if/when/as good returns occur). The floor/upside approach is often contrasted with the safe withdrawal rate approach, where the portfolio is managed for total return and ongoing distributions come out of the portfolio as necessary to cover retirement expenses each year, but there isn't a split with a guaranteed floor and a discretionary upside portfolio.

Yet the reality seems to be that as it is designed and commonly applied, the safe withdrawal rate approach is a floor-with-upside approach.

Setting the Retirement Income Floor

In the traditional floor-with-upside approach, the floor might be invested using either TIPS or an inflation-adjusted annuity, providing the retiree certainty that essential expenses can be covered - notwithstanding the uncertainty of inflation - for the desired retirement time horizon (using TIPS) or for life however long than may be (using an inflation-adjusted annuity).

Thus, for example, if a retiring 65-year-old couple has a $1,000,000 portfolio, and decides that they need $25,000/year in addition to Social Security benefits to meet their essential spending needs, the couple might purchase a single premium inflation-adjusted immediate annuity for their joint life expectancy, with an approximate payout rate of 3.88% - this would require $644,330 to purchase the annuity, and leave $355,670 available to invest for growth, to provide upside to future discretionary spending, and to serve as a reserve for emergencies.

Notably, though, with a safe withdrawal rate approach, a remarkably similar result occurs. Assuming a 4% safe withdrawal rate, the couple would need to set aside $625,000 in order to establish the require funds to sustain a $25,000/year inflation-adjusted stream of income reasonably expected to last for 30 years - leaving $375,000 left over to invest for growth, to provide upside for future discretionary spending, and to serve as a reserve for emergencies.

This parity occurs because of the simple fact that at the end of the day, both the retiree and the insurance company are investing pooled funds to pay out an inflation-adjusted stream of income... and they're both subject to the same capital markets, likely use similar investment assumptions, and may even use substantively similar investment selections! Which means in environments where the safe withdrawal rate is low, because rates are low and/or valuations are high, both the payout rate on SPIAs and the sustainable safe withdrawal rate spending from a portfolio suffer similarly, and both end out with a floor remarkably close to 4%! If rates were higher, the annuity payout rates would likely rise; however, if rates were higher, it would also be more likely the retiree could sustain a withdrawal rate higher than 4% as well.

Not All "Guaranteed" Income Floors Are The Same

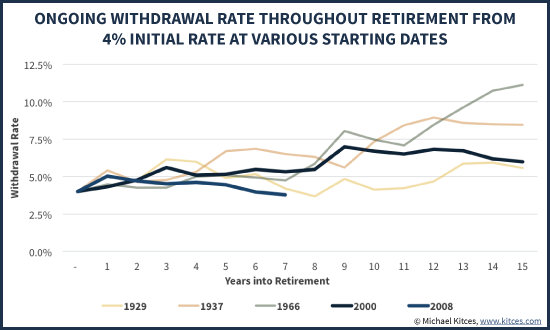

Of course, it's important to note that not all guaranteed (or "guaranteed") floors are the same. While the safe withdrawal rate spending level is set, by definition, at a level that hasn't failed at any point in the past century (at least with respect to the US markets), that doesn't mean some future scenario couldn't unfold that would be worse than anything witnessed historically (although notably, safe withdrawal rate creator Bill Bengen recently showed, and this blog subsequently supported, that even for a year 2000 retiree, the outlook after 15 years still looks far better than any of the historical scenarios that might have stressed a 4% withdrawal rate!).

On the other hand, the inflation-adjusted immediate annuity is backed by a genuine guarantee from an insurance company. Which means even in a scenario worse than any in history, the annuity company guarantee may potentially kee

In addition to the distinction between "never failed in history" and "actually backed by an insurance company guarantee" it is also notable that a safe withdrawal rate floor is fixed for a target time horizon (30 years in the case of a 4% withdrawal rate), while the inflation-adjusted joint survivorship immediate annuity is guaranteed (again, backed by an insurance company) for the lifetime of the couple, regardless of how many years that turns out to be.

The Cost/Benefit Tradeoffs For True Retirement Income Guarantees

All else being equal, any rational retiree would choose an insurance-backed guarantee to "just" the assuredness that the plan has never failed in any historical scenario, and similarly would choose payments that are guaranteed for life instead of just an arbitrary time horizon that could be outlived. However, not all else is not equal.

The key distinction is the liquidity and flexibility that the safe withdrawal rate approach provides, relative to the immediate annuity - including the fact that any excess returns accrue to the benefit of the investor (not the insurance company), and that a premature death leaves any remaining investments to family, charity, or anyone else the decedent designates (not the other annuitants doing business with the insurance company).

Which means in practice, retirees have to weigh the benefit of a not-quite-fully-guaranteed safe withdrawal rate floor with the fully guaranteed annuity, against the cost of liquidity, upside, and legacy assets. And the differences may not be trivial.

After all, as previously discussed in this blog, while the safe withdrawal rate approach is one that self-liquidates the portfolio over 30 years in the worst case (historical) scenario, the reality is that 96% of the time, the retiree still has 100% of his/her principal remaining. In fact, in over 50% of the scenarios, the retiree more-than-quadruples the starting principal value, in addition to sustaining 30 years of retirement spending.

Of course, this fails to address the second guarantee provided by the insurance annuity - that payments will last for life, however long that may be, while in the worst case scenario the safe withdrawal rate approach is expected to deplete the portfolio at the end of 30 years. Yet the reality is that a 65-year-old couple has only a 17.6% probability of actually living for 30 years (the life expectancy for a 65-year-old couple is just under 24 years), and as noted above the retiree also has a 96% chance of having 100% of principal left over to fund unexpected longevity years as well. Which means to truly fail, the couple needs to be unlucky enough to live through an investment environment worse than any found in history (so there's no principal left at the end), and be the approximately one-out-of-six couples that is actually still alive at/beyond the 30-year time horizon. As discussed previously in this blog, when you combine low-probability investment disasters and low-probability longevity scenarios, you can end out with some astonishingly low probability scenarios... many of which could be further "saved" by small mid-course corrections, anyway.

Is Any Retirement Income Floor Guarantee Truly Guaranteed?

Of course, it's also important to note that even insurance company guarantees are only as good as the insurance company backing the guarantee. This is important because, in the context of discussing investment scenarios that cause safe withdrawal rates to fail, which by definition must be worse than anything witnessed in history, extraordinary investment shocks that destroy a 30-year safe withdrawal rate could potentially threaten an insurance company, too.

Similarly, a dramatic shift in population longevity - where a large number of clients all begin to live materially longer and threaten the conservatism of a 30-year time horizon for a 65-year-old couple - could also threaten the health of the insurance company. Granted, these are extremely low probability scenarios - thus why good insurance companies maintain strong financial ratings despite the conceivable possibility this could occur - but again, that's the point. For the retiree who is deeply concerned about such remote possibilities, questioning the safety of safe withdrawal rates inevitably raises questions about the security of the insurance company's guarantee as well - especially for affluent clients whose immediate annuity payments may exceed any state guaranty protections.

This, unfortunately, is the problem with anchoring decisions to remote catastrophic events; it becomes difficult to know which investment strategies - or entire insurance companies - will survive intact.

Choosing A Retirement Income Floor Approach

The bottom line is that choosing between immediate annuities and safe withdrawal rates is not a decision about whether to use a floor/upside approach or not; it's about choosing which floor is preferable, in light of the trade-offs the decision entails.

In the context of the earlier example, the client who annuitizes for $25,000/year of income is guaranteed with inflation-adjusted income for life, but is guaranteed at best to have only whatever the remaining $355,670 portfolio grows to. On the other hand, the client who uses the safe withdrawal rate approach grows that $625,000 allocation to $2.5 million over half the time (even after withdrawals!), in addition to whatever the $375,000 portfolio also grows to as well! Which means the effort to turn "never failed in history" to "guaranteed by an insurance company" (and hoping the insurance company won't also fail in such a catastrophic scenario) can cost the client's heirs a whopping $2.5 million more than half the time, to protect against a scenario that has an incredibly remote joint probability (of worse-than-history bad returns and the insurance company surviving and unusually extended longevity to be around to witness the problem in the first place).

Notably, this trade-off becomes even more problematic as the income need rises relative to the portfolio. If the client's goal was $40,000/year from the portfolio instead of $25,000/year, the client would either allocate all of the $1,000,000 portfolio to the safe withdrawal rate approach, or annuitize the entire $1,000,000 portfolio, which still wouldn't quite produce all of the desired $40,000/year real income stream (given the 3.88% payout rate, and not to mention potentially creating further liquidity issues).

In point of fact, I suspect this is one of the primary reasons why the safe withdrawal rate approach is so radically more common than annuitization strategies in the first place - both produce roughly comparable floor amounts, but the safe withdrawal rate approach doesn't surrender liquidity and control, and retains what in reality is a high probability of something between a substantial and very substantial upside (compared to an annuity approach that guarantees nothing of the annuity's value will be left and no upside can be enjoyed). And for the retiree who wants the annuity guarantee, and a reserve for liquidity and emergencies, the annuity retiree actually has to save significantly more than the safe withdrawal rate retiree - which may be especially problematic when most retirees already fail to save enough.

But the bottom line is that when a retirement spending goal is tied to a 4% safe withdrawal rate, the strategy effectively is a floor-with-upside approach - and one where the odds are overwhelming that the client will preserve all of the original principal, and potentially several multiples thereof, which will be available to either safely raise retirement income further some number of years down the road, serve as a contingency against unexpected longevity, or leave a substantial legacy. The client does have the potential to convert "highly probable" scenarios into something more certain, but the transaction does entail significant trade-offs.

So what do you think? Would you consider safe withdrawal rates to be a floor-with-upside approach? How important is the upside to clients if the floor is reasonably secure? How secure do you consider the safe withdrawal rate floor compared to an annuity guarantee? Is it worth the upside cost? Does the annuity guarantee still feel secure in light of the scenarios it would take to cause a safe withdrawal rate failure in the first place?

Michael,

Thanks for writing this up. It is significant food for thought that will take a while to digest. For now, I just wanted to make sure I get subscribed to see your reader comments.

Best wishes, Wade

At times, annuities can have their place, especially when interest rates are much more favorable, or the individual/couple have more than enough excess cash to fund an annuity for living expenses, and have plenty left over for “legacy” assets or “fun money”.

However, I think the guarantees and income riders tend to be “oversold” on many of these products. I have had many, many, many clients come to me over the years that are looking at various annuity guarantees, and virtually all of them are under false impression that their principal is guaranteed to grow at a prescribed rate, and that said principal is theirs when needed. Most fail to realize (or are not told) that the guarantees are in almost all cases only income guarantees, and that if you extrapolate those guarantees out to their logical end (death), more often than not (logic backs this up) the returns on those guarantees end up having negative (or very slightly positive) IRR’s.

Having said that, for the person that fears running out of money, it certainly brings piece of mind. But in most circumstances, an individual would need to live well beyond their mid-80’s in order to produce a positive return on the annuity (assuming they began withdrawals in their mid-60’s).

I think the insurance companies need to stop scaring retirees with stories of people going broke through the troughs of the bear markets. Even without the assistance of an advisor, and a plain-vanilla balanced portfolio, an investor would almost always outperform current annuity guarantees, with little chance of failure, and with money left over.

I have run basic scenarios on a 60/40 portfolio (Large US Stock/AGG mix), and over the past 40 years (which incorporates a bear market at the beginning and the end) it would produce a SWR of approximately 6.25% for a 40-year retirement. Using a multi-asset approach produced even better results.

Robert,

Just as a quick FYI, even the existing safe withdrawal rate research shows high withdrawal rates if you start 40 years ago. If you want to really test that time period, you need to start in 1966 – where the client has 7 years of flat returns with an initial rise in inflation, and THEN goes through the 1973-74 bear market and the inflation spike thereafter.

Running scenarios for (‘just’) the past 40 years still gives too much credit to the 1982-1999 bull market, unfortunately.

Respectfully,

– Michael

Michael —

SUPERB writeup!

The “never in history” is much weaker than it sounds. We have only 3 or 4 separate 30-year stretches for the U.S. And other countries show less positive histories.

For most folks, 100% SPIA delivers inadequate income for basic needs. Best for them to go portfolio and hope??

Dick Purcell

Great analysis.

The one thing that I am not seeing here in this comparison are fees and expenses. The safe withdrawal literature assumes 4% total withdrawals from a portfolio. If an advisor is charging 1% on assets, the actual withdrawal is 5%. Said differently – when an advisor fee of 1% on assets is included, the portfolio size would need to be $833,000. If the expenses were 2% total (including fund level, advisor level, etc), the portfolio would need to be $1,250,000. The annuity commissions are included in the intial quote and there is no ogoing management fee.

It is also not a question of “which floor” – so much as it is the composition of the floor. There is no reason the two approaches can’t be blended, preserving some degree of liquidity and control while also offloading some degree of inflation and longevity risk.

Great article!

Joe,

You might take a look at some of the separate research on the impact of expenses on safe withdrawal rates. A 1% expense ratio would be more like a 4.4% initial withdrawal rate, not 5%, because the 1% recalculates on a declining account balance while the inflation-adjusted spending does not.

– Michael

Michael,

Excellent overview. This general philosophy on retirement income is similar to the curriculum we teach at the Texas Tech Retirement Income Seminar (next will be November 5 http://riia-usa.org/training/rma-ttu.asp). While we don’t necessarily promote one approach over another, we estimate a baseline of retirement income needs based on an inflation-adjusted SPIA and then introduce acceptance of a risk premium and bequest motive for those who are willing to be flexible with expenses. As Dick notes above, the only way to achieve a higher potential income in retirement is to accept investment risk. However, if risk is real then there will always be the possibility of shortfall. Seeing retirement spending as a continuum from necessities (food, insurance, housing) to pure discretionary (vacations, gifts) allows you to match a portfolio to the amount of risk you are willing to take within each expenditure category.

Michael

Michael,

My problem with the essential/discretionary in this context is that for retirees where the act of retirement is a CHOICE, they don’t view it as essentials vs discretionary.

They view is as an overall target lifestyle. If they can ONLY afford to ensure the essentials but not the discretionary-that’s-essential-to-their-lifestyle, they just keep working until they can afford to maintain their entire lifestyle (at a 4% withdrawal rate, or whatever other floor methodology you want to set).

In other words, in all but extreme forced retirement situations, I question whether the essentials-vs-discretionary distinction you make has practical meaning. A client who can only afford the essentials but not discretionary and must dramatically impair their standard lifestyle has extremely negative psychological ramifications. It’s nice to say they still have food, shelter, and clothing, but they’re often miserable.

– Michael

I agree with you about retirees seeing one target lifestyle, but I think Michael Finke’s suggestion relates more to philosophy. Guaranteeing just base needs via a SPIA is like having a high deductible on your fire insurance policy. Because you recognize that the risk is relatively small, you spend as little as possible and only to protect against real catastrophe. It is the approach I plan to use.

Bob,

Indeed, but my point is that partially guaranteeing a goal is still a failure of the goal.

I view this as the equivalent of buying fire insurance for 50% of your house. If your house burns down, yes you can provide SOME shelter with an insurance policy that provides a 50% payout, so you won’t be homeless. However, if your real goal was to stay in the house, you still failed the goal with a partial insurance strategy.

– Michael

But isn’t it the point of only of buying fire insurance for 50% of your house that you are assuming the other 50% as a matter of self-insurance? (e.g. You have the spare capital available in the event of a loss.)

Taking an Annuity (either/or/combo Straight/SPIA) plus Social Security as a floor and adding on an additional ~4% [give or take] of what’s left for your variable living expenses seems like a viable plan.

Dave,

But the point is that if we’re assuming we need the annuity because the markets will be so catastrophic that the rest of the portfolio will be depleted to $0, there is no self-insurance for the other 50%. All we’re left with is insufficient protection that can’t actually replace the “house” we’ve lost.

If taking an annuity plus Social Security and adding a 4% withdrawal rate for the rest is viable and doesn’t run out of money – which means the 4% withdrawals sustained – then what was the point of the annuity at all? And if the 4% withdrawals don’t sustain, the annuity alone will be insufficient to support the lifestyle anyway.

If we only partially insure a goal and have to rely on that insurance, we still failed the original goal.

– Michael

Michael,

This feels a little apples and oranges to me. If you don’t need the guaranteed floor, then wouldn’t the proper comparison be between a safe withdrawal rate strategy and an immediate variable annuity?

With the immediate variable annuity you get the potential upside on your spending and the benefit of the mortality pooling. So if the person valued maximizing their retirement over a bequest, I would think the immediate variable annuity would out perform the safe withdrawal rate strategy (assuming similar portfolios for both).

Does that make sense?

David

David,

My point is that we treat the safe withdrawal rate approach as though it IS a floor.

We can debate about whether the ‘magic’ number is 4% or 3% or 2% or 1% (that’s not really the point of the post here). But whatever that floor is – spending so low that it’ll be safe through anything just because it’s so low – anything where the market is not catastrophically bad will produce upside that allows for further spending increases.

So in the end, I wouldn’t view safe withdrawal rates as an alternative TO using a floor approach. I’d view it as an alternative way to SET the floor in the first place. With some acknowledgement that it is perhaps a slightly less certain floor, to the extent we can construct scenarios catastrophic enough to be worse than anything in history but not so bad it causes difficulties for the annuity company itself.

– Michael

This is excellent work, Michael. One adjustment I would consider is the idea that the 3.88% SPIA pay-out rate is roughly equivalent to the SWR “set-aside.” It appears to me that on account of risk-pooling, the set-aside should be about 25-40% higher than the cost of the SPIA. Moreover, based upon Wade’s recent research (and my anecdotal experience), I would be more inclined to do without inflation protection on the SPIA. That would bring the SPIA price down to about $460,000 (at current rates).

I would also want to compare other approaches such as a deferred annuity with a GLWB and using term life insurance alongside a SPIA for the healthy to protect against “dying too soon.” I am also curious about new life insurance products with retirement income features, but haven’t “torn them apart” yet. Again (and as usual), excellent work.

Bob,

If your SPIA isn’t inflation adjusted, you need a set aside amount of money to be your “backup for inflation” and then you need that money to perform, or else your standard of living is severely compromised in later years.

If you keep a set-aside for inflation that has an unknown return to deal with an unknown amount of inflation, you’ve essentially recreated a mini-version of safe withdrawal rates all over again, with the same problems and the same risk of depletion if the spending is too high relative to the assets.

So in the end, the non-inflation-adjusted SPIA + a portfolio isn’t necessarily any more secure to provide for the desired goal than just relying on a portfolio alone. The downside of the failure scenarios may look different (since one has a SPIA and the other doesn’t), but in any scenario where one fails (the portfolio depletes and cannot support the original goal), the other scenario fails too (the portfolio depletes and the SPIA alone cannot maintain the standard of living due to inflation).

It seems to me this approach would change the CONSEQUENCES of failure, but not necessarily the PROBABILITY or risk of failure in the first place. Both goals are at risk to at least a partial failure if the portfolio doesn’t perform. And if we think we can set spending low enough the portfolio CAN safely perform, then in theory we could have done that without the annuity, too.

– Michael

Michael,

I haven’t found many clients really even get into these numbers. Rather they bristle at what they give up to get the guarantee of an SPIA. I wrote a little about that a couple months ago for Financial Advisor’s retirement e-newsletter. http://www.fa-mag.com/online-extras/10135-an-unattractive-proposition.html

I think also in these discussions about safe withdrawal rates, we can lose sight of the fact that for many, (not all, of course) the reason they have enough $ to be worried about these issues is that they were able to accumulate funds in first place by getting into the habit of living within their means. Most of my clients have had seasons of high income and low or no income during their lives. They adjust. Barring permanent, substantial uninsured losses or costs of some kind, they are highly unlikely to keep spending at levels that will make them broke. They won’t be happy about it but they will do it. The true odds of them actually running out is near zero.

I am also struck by the number of people who, despite stating they do not care about leaving an inheritance really do. It would embarass them to leave their families only a little after being viewed as successful financially their whole lives. I think that adds to the anti-SPIA reactions.

Again this applies to my clientele and I do not doubt that for others the thinking may be very different.

Anyway just a couple of thoughts for the discussion. Thanks for another great post.

Dan

Dear Michael:

The correct apples to apples comparisons would be annuitizing the SWP approach (a life annuity with variable payout depending on investment returns) versus the SWP or an inflation-protected annuity versus a TIPS ladder. In both cases, the difference between the annuity premium and the amount required to support the SWP will represent the cost of the annuity versus the cost of the relevant SWP and the impact of the “mortality return,” the benefit that surviving annuitants realize as the survivor pool shrinks.

If the costs of the two approaches are equal, then the positive mortality return will leave the advantage with the annuitization approach.

Incidentally, one can show that in the case of long-lived clients, the inheritance available to heirs is frequently larger for annuitization than for the SWP.

Rick,

Can you provide some citations to research to support your last point?

The only pieces I’ve seen to validate this achieved the result by spending down the SPIA first while allowing an equity-centric portfolio to run, which can drastically change the asset allocation of the client’s balance sheet over time. It would be analogous to taking a 60/40 portfolio and just arbitrarily committing to spend exclusively from the 40% in bonds until they’re depleted. Technically, yes, you’ll have a higher average terminal wealth; you’ll also be giving 80-year-olds portfolios that are 90%+ in equities, and I question whether that would really be tolerable for most clients.

In other words, I have yet to see research that validates this when compared apples-to-apples with an SWR approach that also uses a rising-equity glidepath.

Respectfully,

– Michael

I intend to produce an article based on a NAPFA University presentation I developed that makes this point.

I agree that people tend to steer away from immediate annuities, but I disagree that it is a good idea.

Your entire set of assumptions about safe withdrawal rates are based on past history, and I think there have been some substantial changes that will cause the next twenty years to look vastly different than the last 100 years. For example, we are now getting negative real returns on “safe” treasuries. Furthermore, the prospect of 10% nominal returns on domestic large cap equities seems pretty dismal as well. With democracies voting to first monetize and then repudiate debt (while being willing to kill their currency) I think we’ve come up against an era where there is no risk-free investment with real return.

Annuities are guaranteed by government backed insurance at modest levels, just as there’s FDIC insurance coverage on bank accounts, so your premise that the insurance companies might fail would be true for $650K annuities, but not for $250K annuities in my state. I would advise clients to ladder a couple of them (or put them in different spouse’s names) to keep from having too many with one insurance underwriter.

You really pooh pooh longevity risk here. Have you looked around? The old assumptions that people would need to spend a lot in their early years of retirement and then hardly anything in old age have been turned on their head. Everyone these days seems to be spending $130K/year between ages 88 and 103. Whereas average life expectancy may be quite lower, the people who are our clients are typically affluent and educated and have shockingly frequent access to excellent medical care. They simply aren’t dying.

In addition to somewhat unfortunate longevity, there’s another risk to their portfolios; anxious baby boomers. These are “kids” who fully expected to inherit money and find themselves watching their parents gobble it up in assisted living centers instead. As their parents become incompetent the kids are begging a couple hundred thousand here, a couple hundred thousand there. Honestly, I can’t tell you how often I’ve wished an elderly person had their income stream tied up in an annuity where the vultures (of all sorts) can’t get it.

Because that’s the LAST part of this problem: people aren’t really all that competent to manage withdrawals – or bill paying, or budgeting – in their nineties. By that time they’ve got some sort of autopay going on or a kid coming in every few months to pay the bills or some “volunteer” or unbonded help. They are VULNERABLE. A check arriving every month that covers their basic bills is a godsend.

Also, a huge percentage of the population falls into that upper-middle-class land where they retire with a million but land in their infirm old age with a hundred thou and break their hip. A few months in a nursing home and they’ve blown through all the rest of their money and have nothing left to live on when they emerge. If it had been in an annuity they would have gone on medicaid and come back out to still have a cash flow going forward.

You also don’t seem to understand the SECURITY that people get from not being invested in extreme old age. An annuity is a little like Pascal’s wager. If you screwed up and overpaid it sucks, but you don’t care because you’re DEAD. But if you happen to be someone who lives too long it’s absolutely WONDERFUL that you made that bet with the insurance company, and you thank your lucky stars every day. Non-existent real downside, massive upside emotionally. (Except with regard to the heirs, but, hey, were THEY going to send you a check for $2,000 every month when you’re 95?)

In short, I think your numbers overstate the expected return on investments in the next twenty years, understate the safety of annuities, understate the value of longevity insurance, understate the risks elders sustain of having money plundered, and understate the comfort factor of having a certain income.

Agree with everything Wendy says. The article simply dismissed all the downside risk by ignoring it. All the attention was on upside regret. When you choose between two possibilities you must weigh the benefits AND COSTS of each.

Or was the author simply assuming the investor can get all the upside but the downside will be paid for by the taxpayer?

Chris,

You might take a further look at the safe withdrawal rate research.

The downside risks are not ignored, at all. In fact, the client is adopting a radically adjusting spending level specifically to protect against downside risk. If we were merely using average returns, the recommended spending rate would be nearly 60% higher. NOT spending the extra 60%/year for life is the impact of protecting against downside risk and the potential for a sustained period of significantly-below-average returns.

– Michael

Wendy,

You might take a further look at some of the safe withdrawal rate research, which I cannot state fully in the room here.

The withdrawal rates being discussed are based on other time periods throughout history that similarly provided 0% or negative real returns on bonds, and/or multi-decade periods of 0% appreciation on stocks. These kinds of returns are not unprecedented. If we merely looked at average returns, spending levels would be 60% higher (the long-term average sustainable withdrawal rate is about 6.5%, or $65,000/year on a $1M portfolio, instead of ‘only’ $40,000/year). In other words, simply put, the whole reason we use 4% withdrawal rates is SPECIFICALLY because of the exact kinds of low-return periods you’re discussing here. In the early 1900s there was even a stretch where an annually rebalanced 60/40 portfolio generated a NEGATIVE real return compounded for FIFTEEN years. The 4% withdrawal rate was still sustainable in that environment. So for today’s retiree, if the S&P 500 is still at 1,400 in 2027 and bonds continue to yield no more than inflation for the whole 15-year time periods, that’s still a scenario that’s been modeled in the past!

As for longevity risk, a 30-year time horizon for a 65-year-old is already far beyond their joint life expectancy. In other words, the longevity risk is being managed by choosing a safe withdrawal rate for a time period that is already far longer than the client(s) is/are expected to live. If you prefer, make it a 40-year withdrawal rate of 3.5% (instead of 4%) and assume all your clients will live to be 105. (Incidentally, if the average client retiring today really DOES live to 105, then every annuity company in the country will be utterly bankrupt, as that would be an utter actuarial catastrophe for them. Just ask any major insurance company actuary.)

As for things like the risk of elders having their money plundered, it happens to people on fixed incomes as well. The family member skims the money right as it comes into the bank account; I’ve seen it personally.

Regarding the comfort factor of a certain income, I’ve never spoken against it. In fact, I regularly acknowledge in this blog there are decisions we might make for psychological reasons versus financial reasons. But we should still look at them objectively. If the reality is that getting income CERTAINTY gives up 100% of your upside and 100% of your legacy while providing comparable income to strategies that don’t, clients should be aware of that. In point of fact, the existence of the so-called “annuity puzzle” (the fact that even though annuitization appears to be so great, less than 2% of the population proactively chooses to do so) would suggest that perhaps consumers don’t place nearly as much value on this trade-off as we sometimes assume they should.

– Michael

Michael, you have a real powerhouse set of commenters here!

I wrote up a brief blog post about this, and the mentioned figures and further links can be found by linking on (Homepage) next to my name. Here is the text:

I had been asking Michael to get his thoughts out on his topic to help me avoid confirmation bias, as most of what I’ve been looking at recently is decidedly against thinking of a 4% withdrawal rate as a safe income floor. And do recall that the international experience with the 4% rule has been no where near as positive as in the United States.

Nonetheless, still weighing heavily on my mind at present is the demonstration by Bill Bengen that 2000 retirees are still on the path to success using the 4% rule.

I did explore this issue in “Lower Future Returns and Safe Withdrawal Rates.” Most of what I discuss now is based on the methodology described in more detail at that post.

There I was setting current real bond yields to 1%. Michael Finke asked me about failure rates if current real bond yields are 0%.

Essentially, let me now just provide 3 figures of failure rates under 3 different sets of assumptions.

The first figure is calibrated to the standard historical data. With the 4% rule, failure is minimized at 6% with a 50% stock allocation.

The second figure keeps the historical data parameters, except that the average real bond return is reduced from 2.52% to 0% to better reflect current bond yields (which, in turn, are the best predictor of future bond returns). Here, 4% withdrawals and a 50% stock allocation result in a failure rate of 15%.

The problem with the second figure is that the stock return is not adjusted, implying that the equity premium would be even larger than historically, while most pundits suggest that Americans should expect lower equity premiums in the future. In the third figure, real bond yields are 0%, and the historical equity premium is maintained by also reducing stock yields by 2.52%. Now the failure rate for the 4% rule with 50% stocks is 34%.

A 34% failure rate does imply a 66% success rate. So there is a 2 in 3 chance for 4% inflation-adjusted withdrawals to survive for 30 years. But those are not the types of odds you would seek for an income floor to meet basic needs. And the problem would be worse if investors underperform the return indices used for these calculations either because of account management fees or bad market timing decisions.

Michael has made compelling arguments, but I think I am still not convinced that it is a good idea to not build a more proper floor to meet essential needs.

Wade,

If you want to question the 4% rate, that’s fine.

Make it a 3% rate. Now have the same discussion with clients. Would you rather have a 3% rate with full liquidity, full access to your money, a full legacy to your heirs for any unused funds, and what is still a very high probability of having a significant amount of upside and/or additional wealth to leave to the next generation.

The existence of the “annuity puzzle” would suggest that in practice, many people still find this trade-off appealing.

Again, the point here isn’t really to bash annuities at all. It’s simply to emphasize that the safe withdrawal rate approach IS a floor-with-upside approach (we can argue about where to SET the floor, but that doesn’t change the fact that it’s a floor approach).

– Michael

“The existence of the ‘annuity puzzle’ would suggest that in practice, many people still find this trade-off appealing.”

But *why* do they find it appealing? I would suggest that among the primary answers are (a) our general unwillingness to delay gratification (especially if/when the advisor provides a ready excuse); and (b) the lack of advisors advocating for SPIAs (they pay very little and *the advisor* loses control of the money).

Michael,

I certainly and wholeheartedly agree with you that the catastrophic economic conditions would be correlated with insurance company losses, but it isn’t an all or nothing thing here: there are scenarios where Japan had poor returns WITHOUT any atom bombs being involved. You’re better at this than I am, but what did a 60/40 portfolio return in Japan starting in 1990? Stagflation isn’t a remote possibility. Sovereign default by voter choice in the absence of all-out war may be a black swan in the sense that we haven’t seen it before, but when you see swans entering an assembly line filled with black spray paint you have to start to adjust your thinking.

I guess my issue with your historical data is that it doesn’t involve the decline of empires… or more explicitly, you select OUT of the samples the empires in decline. But that isn’t fair: the past 100 years were an age of enormous fossil fuel inputs and enormous productivity gains as a result. But we live in a finite bounded world – we use up the resources and empires start to decline. Ian Morris wrote a tome on “Why the West Rules… for Now” that covers 5000 years of history and the cycle is pretty clear. Empires rise and decline, and civilization waxes and wanes.

We have a fiat currency now and it is fully mortal. It will die. It is already dying, where the copper in a penny is now worth 3 cents. You and I have lived our entire lives on the edge of a hyperinflationary cliff; I think you’re forgetting how LIKELY it is. Now, as with all of us mortals, the big question is when we will die, and it’s a material issue. Three years or thirty years with a semi-stable dollar? I just don’t know. But I wouldn’t bet on the $U.S. backed by the full faith and credit of the U.S. taxpayers to still be in existence in 30 years.

Those sorts of risks are better handled by annuity pools backed by state taxing authorities backed by civilization committing to save old folks from being victimized.

I know you’re trying to answer a simple question: how much can I safely withdraw from my pool to manage my income. And that, in turn, is driving the other big question for the accumulators: what Number do I need? We have to give them concrete answers, I understand that. And it’s fair of you to say that your answers would have to be changed in situations where all bets are off. I get that. But I think the situations where all bets are off is LIKELY in the next thirty years, and that DOES change the answers.

I tell my clients that what they want in old age is for someone to notice if they’re cold and hungry and bring them soup. They can buy into an assisted living continuous care facility, they can join an intergenerational household, they can be good neighbors and members of their church: somehow they need to back up their plans with actual people of good will. Purchasing good will is NOT the best plan, but will do if they can’t figure out how to age well any other way.

I have them buy handicap-accessible vacation homes that their grandchildren will want to summer at with them. I have them buy pretty gold bullion that they bury in the back yard (in a place their kid can find.) I have them in 50/50 equity/tips portfolios AND I turn their 401(k)s into smallish SPIAs with different lives that direct deposit into the bank account I have set up for autopaying their bills so their basic needs are met and portfolios only provide for the discretionary stuff.

I have to wonder how often you’ve been involved in the actual budgeting issues of octogenarians and nonagenarians? Those are the REAL clients we’re investing for when a robust 62 year old comes to you and says they want to retire. You’ve backfit your numbers, but do they work in REAL life? Or does the principle get depleted by “gifts” to “kids” and commission-based variable annuity salesmen who treat them to lunch two or three times?

I just had a case where a woman (not quite widowed by alzheimers, and probably in the first stages of it herself) just unfunded a trust. I asked her about it and she said she’d made a new will. I inquired why she threw out $15,000 worth of estate planning. She said she didn’t remember doing that, that her husband must have done it without her. (Uh, no. She was there every step of the way. I showed her her signatures. She disavowed ever seeing it.) Besides, she said, she wasn’t doing estate planning, she was just doing a new will.

The very next thing she’s going to do is fire me, because she’s become cranky and suspicious and confused by me when I talk (which is how alzheimer’s presents) and, besides, she has a son with a can’t-lose hedging method that uses signals to know exactly when to get in and out of the market each day. (He’s accumulated $50K in capital losses in an up market so far with the fun money she’d given him to play with.) When I pointed out that he is a TERRIBLE investment advisor she said that he needs the practice and his business is in danger so she wants to make sure he at least has her as a client.

So I would add to the issues with your assumptions that you are assuming they will continue to follow the sensible course of investments and drawdowns that you have laid out. I do not think that is true in real life. In real life the insurance company is professionally managed the entire way through, not handed over to Junior for day trading.

Respectfully,

Wendy Marsden, CPA

Wendy,

I have no disagreement with the concerns about elder fraud and financial abuse. I’ve done a lot of expert witness testimony in such cases, both for annuity agents as defendants and against them from their plaintiff clients, tying to my book “The Annuity Advisor”.

That being said, I’ve seen elder fraud and financial abuse take a lot of forms. When family members are going to cheat and take advantage, they can do a remarkably amount of harm with monthly annuity (and pension and Social Security) payments, too.

But not every senior ends out in situations of fraud and abuse. There’s a fine line about how much we should counsel everyone to give up control of their money to an annuity company just to protect the still-limited number of situations where elder fraud ultimately occurs.

Respectfully,

– Michael

Michael,

I’m embarrassed to admit that I didn’t know you did a book titled “The Annuity Advisor”. I’ll have to look it up.

I do AGREE that you’re giving up significant upside potential, I just don’t agree that the benefit – the upside potential – is all that worth it in real terms for real retirees late in their old age.

I would certainly never suggest anyone annuitize everything. I just read your treatise to mean that you would recommend they annuitize nothing because safe withdrawal rates are just as safe. It’s just been my experience that they don’t actually DO the safe withdrawal rates when real life comes and bites them in the butt.

Perhaps I just have rotten clients.

Best wishes,

— Wendy Marsden, CPA

Wendy,

Indeed, ultimately the whole issue comes down to “is the trade-off worth it” – is the marginal improvement between “never failed in history” and “guaranteed by an insurance company” worth the upside that is given up (and will it still provide sufficient protection in the worst case scenarios that at least theoretically could threaten insurance companies, too).

I don’t really mean to dictate the outcome of that trade-off. Clients will have their own tolerances for the trade-off to make that decision.

But both strategies do represent “floor” approaches, and the reality is that for all the history we DO have (which guides both our investment decisions, and the insurance company’s as well), the floors are remarkably close to each other. Which means it’s primarily just a matter of how secure you view one floor versus the other, and the trade-offs you’re willing to make depending on views about the relative security of those floors.

– Michael

Michael —

That claim that after 30 years we have 96% probability of still having at least the initial investment is very very wrong, or at least very very misleading. It omits 30 years of inflation!

In the long excellent Bogleheads “Trinity update” thread of a while ago, based on Wade’s work, I challenged that 96% claim as being crazily out of whack with distributions produced using Monte, and also distributions using “historical duplicative overlaps.” My analyses showed that the probability is only 50-something.

In that thread, Wade and I went back and forth on it and Wade found Bengen had left out inflation.

If you want to check this, go to the link below, which should take you to that thread’s page 9, and scroll down 4 or 5 comments to the first one with red dice at right . . . Then follow back and forth between Wade and me. (Sadly, changing Bogleheads coding changed all my graphs to HTML gibberish.)

http://bit.ly/LiOs43

This means the claim that there is 50% probability of quadrupling the balance over the 30 years is also way off.

Dick Purcell

Dick,

I never said the amounts were inflation-adjusted (and for the record, it’s Bengen’s data and research, not mine).

But I’m not sure what the point is of inflation-adjusting in this context, either. I’ve never heard a client say “Oh no, I don’t want to just leave $1M for my kids; I want to leave enough money to provide an inflation-adjusted equivalent of $1M!”

In other words, when we’re talking about legacy goals in this context, the point is simply “if we follow a safe withdrawal rate approach, there’s a high likelihood of a big pile of money left over.” At the point the client dies, I suppose we can discount the value of that big pile of money back to what it would have been in 30-years-ago dollars, but I don’t think it’s really germane at the time whether the 30-years-prior discounted value would have been $500k or $1M or $2M. It’s still a lot of money left over relative to the original starting account balance.

– Michael

Good stuff, but you are comparing current annuity rates, which need to reflect current low investment rates (as an aside here, SPIAs cannot be invested in equities, so your catastrophic retort is weak), vs a “historical” equity portfolio. I’m not saying the equity ssumptions should be changed (though some are posturing along those lines); just that current annuity are low.

Morever, inflation adjusted SPIAs are backed by TIPS; insurers do better inveting in corporates. Though not fully inflation adjusted, fixed increase annuities offer bettered tares. Granted, currently offered annuities, and using TIPS is all that is out there, but this is just to indicate why the income levels are coming out close.

Steve,

I realize that we’re looking at annuity rates in currently weak markets, but that’s partially the point. If rates were higher the annuity payouts would be better. But as Pfau’s research has shown, higher rates could also support higher safe withdrawal rates, as well. We often have an equity-centric conversation about safe withdrawal rates, but the withdrawal rate research is based on balanced portfolios with both equities AND bonds.

Accordingly, this means the research puts forth the 4% withdrawal rate specifically because that’s the WORST combination of bad rates and bad equity markets we can find in history. Which in turn means the reality is that low points in annuity payouts are correlated to low points in safe withdrawal rates, and higher yields ultimately supports higher levels of both (although certainly the relationship is not modeled quite as clearly on the safe withdrawal rate side).

– Michael

Sorry, but you are again mixing apples and oranges in your comparisons and conclusions. In this case you are comparing the results of a portfolio against a single historical annuity result. To make a fair comparison, you would have to look at a portfolio of historical annuity results.

Further, on the annuity side you are using retail rates which incorporate annuity manufacturer expenses (including those for distribution and investment management) and profit margins, but on the portfolio side unloaded market rates are used.

Differences in taxes are also a factor.

Bottom line, access and legacy is obviously not as good under a payout annuity because _by_ _definition_ those benefits are _traded_ in a payout annuity for the ability to “take” an enhanced income without jeopardizing running out of that enhanced income amount.

Steve,

Actually, we’re looking at a single historical annuity result against a single historical portfolio result. The safe withdrawal rate is, by definition, based on the one single worst case scenario we can find in history, which is what defines it as the “safe” withdrawal rate (because it’s low enough to survive the one worst scenario we can find, and therefore would survive every other as well).

And the safe withdrawal rates I’m citing here are consistent with expenses of approximately 0.15% associated with index ETFs (although not any additional separate advisor fees).

In any event, the real point of the post is that safe withdrawal rates IS a floor-with-upside approach, which typically provides for several multiples of the starting principal left over, in addition to sustaining spending for life, and this is widely misunderstood. We can argue about whether the safe withdrawal rate floor is 5% or 4% or 3% or whatever, but that doesn’t change the principle that it’s a floor-with-upside based approach (with a remarkably high likelihood of significant upside). The debate about exactly where to draw the floor is a separate (albeit also important) conversation.

– Michael

Saying that there is a safe withdrawal rate from a portfolio doesn’t need to be compared to an annuity.

But if you are comparing what it can provide to an annuity, the level of the floor that can be provided is paramount. Upside legacy or access are side shows. The key to the annuity puzzle is to get people to focus on what they are after; in the case of this article it is by far safe income level first. Considering income levels that payout annuities can provide in various markets is key to making the comparison

“the research puts forth the 4% withdrawal rate specifically because that’s the WORST combination of bad rates and bad equity markets we can find in history.”

I think, in fact, the research is saying that 4% is the HIGHEST withdrawal rate that one can take out with X% assurance, and so for a fair comparison (as has been pointed out an immediate variable annuity would even be better) one should similarly at least look at representative rates one could historically be guaranteed under a SPIA (albeit adjusting for continual improved mortality).

Seems like the discussion between Michael and Wendy may call for a combination of both a longevity annuity where the person buys both a deferred SPIA for age 80 or thereabouts, and a stock/bond allocation that lasts until then. How do either of you see that?

Great discussion. Thanx

Brian, I think that makes perfect sense. In practice I don’t actually attempt to get them to buy an annuity until sometime in the late seventies anyway. Not only do we get a higher payout that way, but by that time they’ve got a better idea about who will be the second to die. I usually couch the annuity discussion in terms of handling required income when one person’s income is gone. Plus by then they are less interested in being exposed to the vicissitudes of the stock market. (I find myself insisting that they DO keep something in equities!)

My concern here, and the reason I chimed in so strongly, is that the robust 62 year old trying to determine if they have “The Number” is being unduly warned away from annuities. They are largely clueless about how bad they will be with staying the course as time goes by. I just don’t want them to get the idea in their heads that annuities are bad and you can cover the risks just fine with their asset allocation portfolio. True at 62. Not true at 82 when you include all the OTHER risks I mention above.

Thanks for sharing, Wendy. I have surmised that retirees are not really ready for annuitizations at retirement – retirement takes a while to get “used to”. The average purchase age of about 72 gave my “theory” some data credence, but your comment is this first documentation I have seen along these lines. In these respects, the purchaser doesn’t forgo that much in the way of so-called mortality credits by waiting, as mortality rates are still not that steep in 60’s & early 70’s and they are shared over more years in younger purchases (I know that’s vague, but you don’t want to try explain it within the scope of the current products).

Brian,

I’m intrigued by the longevity annuities at least conceptually, and will be covering them later this year in great depth in the newsletter.

My greatest worry on the longevity annuities – which I’m already hearing early on from a few of the annuity companies offering them – is that while they’re great conceptually, people are even more loathe to buy longevity annuities than traditional SPIAs (which already have abysmally low implementation rates).

Whether we can get over the mental hurdles of a longevity annuity remains to be seen. But from the theoretical perspective, my initial impression is very good.

– Michael

Michael,

One thing not particularly mentioned is that in the SWR scenario the investor (whether she has an advisor or not) has to have the discipline both to stick with the spending rate and with the investment plan. Purchasing an annuity (leaving aside that a profligate spender could sell the annuity) obviates both these requirements.

Advisors sizing up clients on this score (and investors sizing up themselves) is no easy task. And of course it could go along just swimmingly for a while and then the investor’s spending discipline could break down or the investor could change advisors and the investment discipline could break down.

Thoughtful viewpoint to set a bogey or a target – and I generally land in the “do both” camp.

I would encourage the prospect of using an aftcasting technique versus monte carlo in the 4% withdrawal strategy. Aftcasting will allow the TIMING of correlations to match between stocks, bonds, and inflations in sequential years.

Of note –

1) this analysis has no fees, inclusion would increase failure rates.

2) Note the average annual returns of bonds – using a broader universe used today.

3) Today a 60 year old couple has a life expectancy of 92, so a 50% chance of living beyond 32 years…

4) monte carlo analysis will not capture the “saver vs spender” average return, sequence of returns for equities, AND bonds.

5) most failure rates occur in clusters, with the majority of 35 year periods Ending in the 90’s and 00’s, meaning they started in the 60’s and 70’s. Represented by high market volatility, low yields, and prospects for higher inflation

6) the dichotomy of failure vs nonfailure with high generated balances.

7) the significant increase in failure rates living just an additional 5 years, no matter what portfolio.

8) maybe most important is the ability to get a better annuity product, ie a living benefit with a payout starting at 5% and increases in income, thereby funding the floor with a much lower portion of the portfolio. This is not the “generic” income rider feature you see.

Simply, if you have the desire to protect against living longer, you can get paid addtl yield in the annuity because of lifetime income. If you do not think you will live, don’t pay for it.

The paper is on the SSRN: 1641382

Dan notes that using annuity products with living benefits with increasing income over time. The likelyhood of an increasing income is quite low. The hurdle rate to increase the income base becomes so high in the later years that it is quite difficult to not only increase the income but also very difficult to leave any money at death especially if you are one of those couples that actually lives to 92+. I am intrigued however about that strategy (I would love to see Dan’s research on this) but goes beyond the scope of Michael’s article. Michael, great post! You are amazing at responding to the countless responses that miss the point of your article.

Good point Paul, in fact I would take your comments a step further to say that most living benefit riders with a high water mark income feature have little to no possibility of providing pay raises in retirement, let alone keeping up with inflation. There are many withdrawal benefits, both on variable and fixed products, that offer an increasing income stream, they are lesser known because most annuities are looked at for the rollup component. With that said, I like the way Mike presented this debate. Living benefit riders only pay off when a client lives long enough to exhaust the underlying assets of their annuity and continue to receive income. The annuity value proposition is truly taking income while leaving no death benefit. Like all insurance, annuities are a pool of clients, your client will probably benefit from the annuity if they live longer than the average. The general problem with annuities is in-efficient usage, this can also be a positive as you can seek to help your client use the products more efficiently, hence placing them on top of the insurance pool.

1

Michael,I am writing this in March 2013 and as everyone knows, immediate annuity rates are at historic lows. A little research into historical immediate annuity rates seems to show that for a 65 year old male the spread between a life only IA and Treasury rates is 3.8% to 4.0% and for a 70 year old the spread is around 5.3% (if you have any data on this I would love to know). If someone is retiring in 5 years what will Treasury’s be then? Pick a number. If 6% then IA rates might be 9% to 10%. And don’t forget income taxes; the IA enjoys a significant exclusion ratio.

Thanks for a great article

Randy,

Be careful not to compare principal-amortizing payments to interest-only payments.

SPIA payments are part income, part liquidation of principle, so the payout “percentage” of a SPIA will ALWAYS be higher than a bond if you only spend interest from the bond.

However, if you spend down principal AND interest from a bond, you can replicate the payment stream of an annuity – including the fact that, just like annuities, a portion of each payment will be principal and a portion will be interest.

Of course, the SPIAs payments are life contingent and can continue past life expectancy – in exchange for the risk of dying early – but the AVERAGE expected return of a SPIA at life expectancy is nothing more than the expected return of a self-liquidating laddered bond portfolio over the same time horizon. If it was anything otherwise, annuity companies would all become insolvent!

Respectfully,

– Michael

That isn’t correct. A life contingent payout annuity amortizes principle, interest, AND mortality credits over the life of the contract. The insurance company can enable this because it redistributes account balances (reserves) of those that die to make the amortization payments to those that live. See my article “Retooling for Success in the Post-Retirement Market” in the Society of Actuaries Product Development Section February 2012 newsletter at http://www.soa.org/news-and-publications/newsletters/product-development/pub-product-development-details.aspx

Steve,

Certainly, the SPIA owner who OUTLIVES life expectancy will generate mortality credits, offset by those who don’t survive so long.

But the AVERAGE buyer of a SPIA shouldn’t receive any mortality credits. The average buyer has average mortality, lives to (but not beyond) life expectancy, and earns no mortality credits.

If the average buyer were to receive mortality credits, the annuity companies would average payments out that exceed their incoming premiums plus growth in the aggregate, which would eventually lead to bankruptcy/default of the insurer. If the insurer is economically viable, it has to net out as a zero sum (or technically a slightly negative sum, given operating costs and a profit margin expectation for the insurer).

– Michael

No. Mortality credits are part of the calculation to determine the single premium required to buy the amount of guaranteed income to be paid out (or alternatively the amount of income that will be purchased by a specified single premium).

The calculation is for ALL purchasers (no one knows which will die early and which will die later), but actuaries do know how many are EXPECTED to die each year. They also project how much interest they can expect to earn on the account values in the future. {In both cases they of course include risk margins.]

They then model, all the way out to the end of the mortality table when the last of the purchasers are expected to die, how much single premium they will need to pay out the income amount to all who live each year, taking into account the assumed interest earned on the account value.

Key to this equation, is the fact that those that die each year relinquish any claims to their account value. Those amounts relinquished are the mortality credits that are implicitly taken into account in the calculation of the single premium – which benefits ALL purchasers.

The alternate approach described in the paper cited above, does the calculation as an amortization wherein the mortality credits are explicitly displayed.

An simple analogy to this can be discerned from say a one year term life insurance policy. There, for a small premium, those that die get a large payoff but those that live get nothing. But the reason the insurance company can make the large payout is because everyone purchasing the policy pays an implicit cost of insurance (the opposite of mortality credits, but a similar element that make the cooperative nature of insurance work).

Steve,

Just a follow-up to this, as a hopefully-not-too-simplified example might help this discussion. I think I’ve followed your point here, so please correct my math if I’m still off.

Let’s assume 10 annuitants who each put in $100,000 (total pool $1,000,000), and the insurer can earn 5%. The mortality table for the annuitants anticipates that on average 1 will die every year, such that all 10 will be dead after 10 years.

The annuity payments in the aggregate would be $129,505 (which amortizes the principal down to zero at the end of 10 years at 5%), if everyone lived for all 10 years, which would mean the annuity payments for each of the individual 10 annuitants would be $12,950.50 per year per person (ignoring overhead costs and profit margins for the insurer for now).

However, the caveat is that if we really kill off 1 person each year for the 10 years, then we’ll only end out paying out $712,275 in payments (far less than the $1,000,000 plus growth), so the additional expected value from future forfeited payments (the mortality credits) is then also redistributed, making the effective payment higher than $12,950.50 per person starting out from year 1. If I’m doing my late-night spreadsheet math correctly then I’d end out with a payment of $21,946.52 instead, given the arbitrary 1-death-per-year mortality table I’ve assumed here.

Are we on the same page now? 🙂

– Michael

Yes, I think we’re on the same page now.

We actuaries, though, think of the mortality credits thrown back into the pool as coming not so much from the forfeited payments as the forfeited account balance (reserve/amortized value) on death. However, I now realize that you are quite correct in how you formulated it because the present value of expected payments a moment before death equals the reserve.

I hope you now see why SPIA’s are quite distinct financial instruments that can’t be matched by any other, albeit with its minuses as well as its plus of payout amount leverage (and lifetime guarantees too, though I personally think this is the lesser plus).

Steve,

Indeed, funny how we can all look at the problem from a different perspective and frame the payments/values so differently! 🙂

Thanks for your patience with me in the conversation!

– Michael

I agree on the numbers. Still there are clients who feel It comforting to have a floor. Purely emotional decision, as most decisions are.

I don’t know where you got your annuity rates from, but the SPIAs that I have access to are paying out around 5.5% for a 65 year old couple on a joint and survivor basis. It would only require about $455,208 to provide $25,000 of income for the rest of their lives. If it were on a single life, it’d be more like 6.75% payout.

Also, according to Monte Carlo curves, the 4% withdrawal is no longer the standard to prevent running out of money. It’s more like 3%.

One other thing is the rate of return that you used to get to the end result of $2,500,000 over 15 years. Don’t take this as rudeness, but show me anywhere in history where the market went up every single year by 12%. It’s never happened. You need to be careful when talking average returns versus constant returns. The market does not constantly return 12% year after year (2008 for example was about -40%). There are some time periods where the market has “averaged” 12%, but nothing constant. If someone started withdrawals of $25,000 in the year 2000, they would only have grown their money to around $760,000 after withdrawals. That’s only a 1.2% constant return per year including withdrawals. Pretty far short of $2,500,000.

Hopefully this is helpful to you all.

What would you think about annuity (or TIPS) to cover a SS gap between age 55 and 70?

Hi, I developed a app to help people calculate and analise loans, it would be awesome if you tried it and gave me some feedback so I can improve it and add more functionalities:

https://goo.gl/YTGOKe